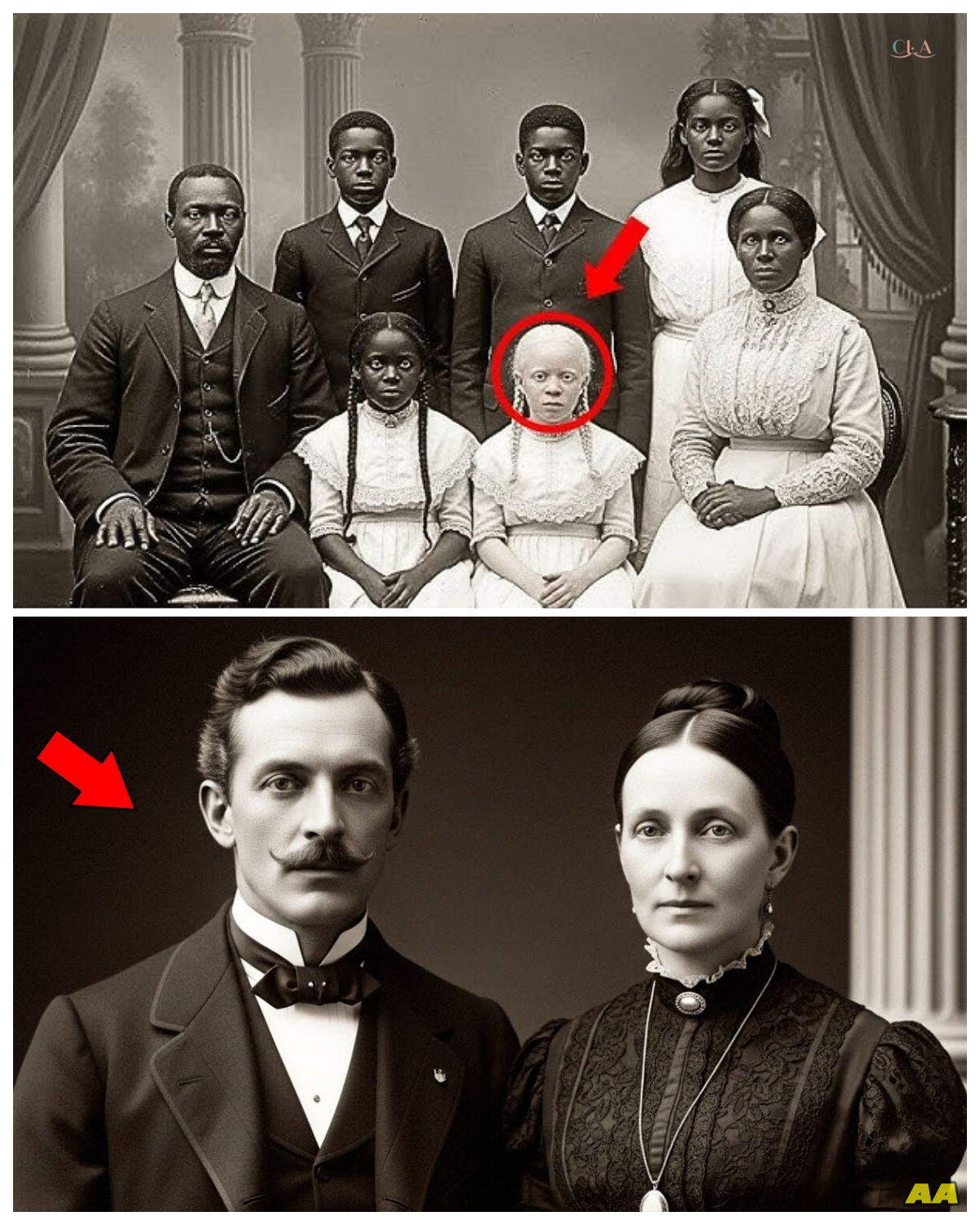

Experts find 1847 dgereroype of couple.They enlarge it and can’t believe what they see.

Rain gently tapped against the windows of the Metropolitan Museum of Art while Dr.

Carman Rodriguez finished cataloging the last box from the Harrison Williams donation.

It was a gray Tuesday in November, and the historical photography specialist had spent 3 weeks meticulously reviewing each piece of the extensive collection that had arrived at the museum after the death of Mrs.

Eleanor Harrison Williams.

Just one more box and I’m done for today, murmured Carmen, adjusting the white cotton gloves that protected the delicate historical pieces.

At 42, she had dedicated her life to studying 19th century photography, but she had never lost the excitement of discovering hidden treasures in private collections.

Upon opening the small navy blue velvet box, she found a perfectly preserved dgerype.

The silverplated copper plate gleamed under the specialized light of her workstation, protected by original glass that had withstood the passage of time.

Carmen felt a thrill of excitement.

Dgeray types from 1847 were extremely rare in the United States, especially in such good condition.

The image showed a young couple, a man of approximately 30 years with a carefully groomed mustache and a woman with dark hair pulled back in an elegant bun.

Both were dressed in formal period clothing, but something in their expressions immediately caught Carmon’s attention.

They didn’t have the typical rigidity of portraits from that era.

Their faces showed an intimacy uncommon in formal photographs of the period.

“Interesting,” whispered Carmon, taking her magnifying glass.

“Very interesting.

” After 20 years examining historical photographs, she had developed a special instinct for detecting exceptional pieces.

This dgerotype had something different, something she couldn’t yet explain.

On the back of the box, she found a small handwritten label with faded ink.

New York, 1847, JM and MC.

The initials were written in elegant but trembling calligraphy, as if whoever had written them was nervous or excited.

Carmon felt her pulse quicken.

There was something in that image that told her she had found something more than a simple family photograph.

The next morning, Carmon arrived early at the museum’s digital restoration laboratory.

The specialized technician, Miguel Santos, had already prepared the highresolution scanning equipment they used to digitize the most valuable pieces in the collection.

Good morning, Carmen.

What do we have that’s special today? asked Miguel while adjusting the professional scanner parameters.

At 35, Miguel was considered one of the best art digitization technicians in the country, and his collaboration with Carmon had resulted in several important discoveries.

A dgereroype from 1847 that I found yesterday in the Harrison Williams donation, responded Carmen, carefully placing the piece on the scanning table.

There’s something special about it, Miguel.

The image quality is exceptional for the era, and the couple’s expression is unusual.

Miguel examined the piece with his professional magnifying glass.

You’re right.

The level of detail is impressive.

Whoever took this photograph was a master of dgereroype technique.

Let’s scan it at 4,000 dpi to capture every minute detail.

For the next 40 minutes, the scanner worked meticulously capturing every fiber, every reflection, every shadow of the historical dgerpype.

Carmen observed the process with the patience of someone who had done this hundreds of times, but with the excitement of someone who sensed that something extraordinary was about to be revealed.

Ready, announced Miguel.

Now, let’s see what secrets digital enlargement reveals to us.

On the 32-in screen appeared the highresolution digitized image.

Carmen approached, studying every detail with attention.

She immediately noticed elements she hadn’t been able to see with the naked eye.

The texture of the woman’s dress revealed intricate embroidery.

The man’s brooch showed a complex heraldic design.

Miguel, can you enlarge the area of the man’s brooch? asked Carmen.

Upon doing so, the small brooch grew to occupy a considerable portion of the screen.

What they saw left them speechless.

A perfectly detailed heraldic shield that Carmen recognized immediately.

It can’t be, murmured Carmen, moving closer to the screen.

That shield? I need to make urgent consultations.

Carmon spent the next 3 hours in the museum’s specialized library, surrounded by volumes on American heraldry of the 19th century.

The yellowed pages of the old books creaked under her fingers as she desperately searched for any reference to the shield she had seen in the Dgeray’s brooch.

“Here it is,” she finally exclaimed, pointing to an illustration in the armorial of New York’s noble families from 1834.

The heraldic shield was identical to what she had seen in the photograph.

A rampant lion on a gold field with a ducal crown at the top and a Latin inscription that read Veritas at Onor.

The shield belonged to the Mendoza Carvajal family, one of the oldest and most influential aristocratic houses that had immigrated to America from Spain.

Carmon felt her heart racing as she read the family description.

The Mendoza Carvajels had been advisers to Spanish royalty for centuries.

And in 1847, the year of the Daggera type, the family heir in New York was Don Hwain Mendoza Carvajal, 31 years old.

JM murmured Carmen, remembering the handwritten initials in the box.

Waqin Mendoza.

But who was MC? She continued investigating, but found something that left her perplexed.

According to official records, Don Haqain Mendoza Carvajal had died unmarried in 1851 with no known descendants.

However, other documents suggested he had had a scandalous romance that had been carefully erased from the family’s official records.

Carmen decided to consult with Professor Eduardo Ramirez, the most respected historian of 19th century America, who regularly collaborated with the museum.

Professor Ramirez, 73 years old, had dedicated his life to studying American aristocratic families and new secrets that had never been officially published.

“Professor, I need your help with something very delicate,” Carmon told him over the phone.

“I found what I believe is a dagger type of Don Huain Mendoza Carvajal from 1847, but he appears with a woman whose identity I don’t know.

” The silence on the other end of the line extended for several seconds.

Finally, Professor Ramirez responded with a carefully controlled voice.

Carmen, can you come to my office immediately? There are aspects of the Mendoza Carvajal history that have never been made public.

Professor Eduardo Ramirez’s office was located on the top floor of a historic building in Greenwich Village.

Carmon climbed the worn marble stairs, feeling anticipation grow with each step.

The walls of the 19th century building seemed to guard secrets, just like the photograph she carried, carefully protected in her portfolio.

Carmen, please come in.

Professor Ramirez greeted her, an elegant man with completely white hair and penetrating blue eyes.

His office was a labyrinth of old books, historical documents, and portraits of aristocratic families that seem to watch from the walls.

“Professor, before showing you the photograph, I need to know what you know about Donqin Mendoza Carvajal’s personal life,” asked Carmon, sitting in a vintage leather chair in front of the desk.

Professor Ramirez served himself tea and remained silent for several minutes, as if carefully deciding what information to reveal.

Carmen, what I’m about to tell you has never been officially published.

Don Hwainin Mendoza Carvajal had a romance with a woman who didn’t belong to the aristocracy.

An extraordinarily beautiful and intelligent woman, but whose social origin made the relationship completely unacceptable to the family.

“Do you know her name?” asked Carmen, feeling she was approaching the truth.

Maria Carmen Delgado Eva was the daughter of a humble textile merchant but had received an excellent education.

She worked as a governness for wealthy families responded the professor getting up to search for a document in one of his private filing cabinets.

Carmen felt a chill.

MC Maria Carmen the initials on the box match perfectly.

Exactly.

Now show me that photograph,” said the professor with a mixture of excitement and somnity in his voice.

Carmen carefully extracted the highresolution print of the Dgera type and placed it on the desk.

Professor Ramirez put on his glasses and examined the image for several minutes.

“Extraordinary,” he finally murmured.

“This photograph is the only visual evidence that exists of their relationship.

” Carmen, do you realize what you have here? This dgereroype was probably taken in secret as a kind of symbolic marriage between them.

“What happened to Maria Carman?” asked Carmen, though she sensed the answer would be painful.

Professor Ramirez removed his glasses and looked directly at Carmen.

Maria Carman mysteriously disappeared in 1848.

Nothing was ever heard from her again.

Don Haqain fell into a deep depression and died 3 years later supposedly from tuberculosis though there are rumors he died of sadness.

The next day Carmen and Professor Ramirez headed to the New York City archives located in an imposing neocclassical building near city hall.

The official who received them, Isabel Moreno, was a 50-year-old woman with an impeccable reputation in historical records research.

Professor Ramirez, it’s a pleasure to see you again,” Isabelle greeted, leading the researchers to the specialized consultation room.

“Your message yesterday intrigued me greatly.

It’s very uncommon to request information about people who disappeared in the 19th century.

” Carmen explained in detail the discovery of the Dgera type and the connection with Maria Carmen Delgado Eva.

Isabelle listened attentively, taking notes in her specialized notebook.

Maria Carmen Delgado Eva repeated Isabelle, consulting her digitized archive system.

Let’s see what we find.

Here we have birth records.

But let me search in the more sensitive documents.

For the next 2 hours, Isabelle meticulously reviewed old files, parish records, and municipal documents that had been preserved for centuries.

Carmen observed the process with fascination, understanding that each document could contain the key to solving the mystery.

“Here’s something very interesting,” Isabelle finally announced, pointing to a handwritten document dated March 1848.

“It’s a record from St.

Paul’s Chapel.

Maria Carmen Delgado Eva requested documents to travel to France.

Carmon and Professor Ramirez exchanged significant glances.

France? Why France? asked Carmen.

According to this record, Maria Carman declared she had family in Paris and needed to travel urgently for family reasons.

But there’s a marginal note that says, “Verify with higher authorities,” continued Isabelle.

“But the most disturbing was in another document.

Here’s a record from the municipal police from April 1848.

Maria Carmon was last seen at an inn near the border with Canada, but she never crossed the border.

Her belongings were found abandoned, including a letter that was never sent.

“What did the letter say?” asked Professor Ramirez urgently.

Isabelle consulted another document and read.

The letter was addressed to someone called JM.

It said literally, “My love, if you’re reading this, it means I haven’t been able to reach our meeting place.

You know, our love is stronger than your family’s threats.

I’ll wait for you in Paris until you can join me.

Always yours, MC.

” Carmon realized that Waqin and Maria Carman had planned a romantic escape, but someone had prevented Maria Carmon from reaching France.

The most mysterious thing was that the Mendoza Carvajal family had officially reported that Maria Carmen had arrived safely in France.

While police records told a completely different story.

Days later, Carmen managed to locate Pilar Ruiz Morales, 85 years old, whose great-g grandandmother, Espiranza, had worked as a cook in the Mendoza Carvajal House during that time.

Carmen visited her at the Sunset Manor Nursing Home in the Upper West Side.

Mrs.

Ruiz, we’re historical researchers and we’re investigating the history of the 19th century Mendoza Carvajal family.

Carmen explained carefully.

Pilar’s eyes immediately lit up.

Ah, the Mendoza Carvajayels.

My great-g grandandmother Espiransa worked for them for many years.

She always said they had done terrible things but never wanted to give details until she was dying.

What exactly did she tell you? asked Professor Ramirez.

Pilar remained silent for several minutes as if deciding whether to tell a story she had kept for decades.

My greatg grandmother told me that in April 1848, three men brought a young woman to the Mendoza Carvajal house in the middle of the night.

The woman was unconscious but alive.

Carmen felt her heart racing.

What happened to that woman? According to my great-g grandandmother, the woman was taken to a room in the basement of the house.

Espiransa saw her briefly and said she was very beautiful with dark hair and dressed in traveling clothes.

But most importantly, the woman wore a small medallion with the initials MC.

Espiransa had to take food to the basement for three days.

The woman was alive but very ill.

She cried constantly and repeated a name, Wain.

On the fourth day, when Espiransa went down with food, the room was empty.

Professor Ramirez asked, “What happened to Maria Carmen?” My great-g grandandmother never knew for certain, but that night she had seen the family’s men loading something heavy into a carriage.

Espiransa heard a conversation where they mentioned the old woodlorn cemetery and that no one would ever find her there.

Carmon realized they had discovered evidence of what had probably been a kidnapping and possibly a murder.

After obtaining Pilar Ruiz Morales’s official testimony, Carmon contacted Dr.

Laura Mendesal, a forensic archaeologist from Colombia University specializing in historical investigations.

Carmen, what you’re telling me is extraordinary.

Laura told her during their meeting at the archaeology laboratory.

If we really find physical evidence, this could rewrite part of 19th century American social history.

For 2 weeks, Carmon worked tirelessly to obtain the necessary permits from the city and the department of historical heritage.

The dgeraya type historical testimonies and Pilar’s statement provided sufficient evidence to justify the investigation.

On a cold December morning, Carmen, Laura, and a small team of archaeologists headed to the old section of Woodlorn Cemetery.

The cemetery, partially abandoned during the 20th century, still preserved many old 19th century graves.

According to the testimonies, Maria Carman would have been buried in a remote section of the cemetery, probably without an official marker, explained Laura while examining the historical site plans.

The team used ground penetrating radar to scan the terrain for anomalies that could indicate unmarked burials.

After 3 days of meticulous searching, they found several irregularities in a remote section of the cemetery.

Carmen, we’ve found something, announced Laura on the fourth day.

There’s evidence of a burial that doesn’t correspond with the cemetery’s official records.

The depth and type of soil disturbance suggest it was done hastily.

With extreme care, the team began excavation.

Carmon observed the process with a mixture of scientific excitement and human sadness, knowing they might be about to find the remains of Maria Carmen Delgado Eva.

After several hours of meticulous work, Laura made a discovery that left the entire team speechless.

Carmen, come here immediately.

We found something extraordinary at the bottom of the excavation, partially preserved by soil conditions, was a human skeleton.

But what made Carmen feel a chill was what they found next to the remains.

A small silver medallion blackened by time.

After delicate cleaning, the medallion revealed its secret.

Engraved in the silver were the initials MC in elegant 19th century calligraphy.

Forensic analyses confirmed Carmen’s worst suspicions.

Doctor Laura Mendisabal found clear evidence that Maria Carmen Delgado Eva had died from cranial trauma caused by a blunt object.

Carbon 14 studies confirmed the death had occurred between 1848 and 1850, coinciding perfectly with the chronology of her disappearance.

Carmen decided it was time to make the story public.

She organized a press conference at the Metropolitan Museum of Art where she would present all her findings.

News of the discovery had begun to leak in academic circles and several media outlets had expressed interest in the story.

Ladies and gentlemen, began Carmen in front of the cameras and journalists gathered in the museum’s conference room.

What began as the simple cataloging of a donation has become the discovery of one of the most tragic and criminal love stories of 19th century America.

Carmen methodically presented all the evidence, the original Dgera type, historical documents, archive testimonies, Pilar Ruiz Morales statement, and finally the remains and medallion found in Woodlon Cemetery.

The evidence is conclusive, continued Carmen.

Maria Carmen Delgado Eva was kidnapped by order of the Mendoza Carvajal family when she tried to meet Donqin in France.

She was held in the family house for several days and subsequently murdered to prevent her relationship with the family heir from becoming public.

Professor Ramirez added historical context.

This case perfectly illustrates how 19th century aristocratic families used their power and influence to control not only family fortunes but also the lives and destinies of people they considered threats to their social position.

A reporter asked, “Doctor Rodriguez, what happened to Don Huain after Maria Carmen’s disappearance?” According to our investigations, Don Huain never knew the truth about what had happened to Maria Carmen.

His family made him believe she had reached France and decided to start a new life there.

Waqin spent the rest of his short life waiting for news from her and died in 1851 without knowing she had been murdered by his own family.

After the press conference, Carman received intimidating calls from lawyers representing current descendants of the Mendoza Carvajal family, but she stood firm.

Maria Carman deserves to have her story known.

Her memory is not for sale.

6 months after the press conference, Carmon laid the last stone on the monument that New York City had authorized to honor the memory of Maria Carman Delgado Evga.

The monument located in a renovated section of Woodlorn Cemetery bore an inscription that Carmen had written personally.

Maria Carmen Delgado Evga 1817 1848.

Her love was stronger than the conventions of her time, and her memory is more lasting than the power that tried to silence her.

The original degarotype now had a place of honor in the Metropolitan Museum’s permanent exhibition, accompanied by the entire story Carmen had discovered.

Thousands of visitors had come to see the photograph and learn the love story that had defied the social barriers of the 19th century.

Carmen, you’ve achieved something extraordinary.

Professor Ramirez told her during the monument’s inauguration ceremony.

You haven’t just solved a historical mystery, but you’ve given voice to a victim who had been silenced for more than 170 years.

Pilar Ruiz Morales, now 86 years old, had insisted on attending the ceremony.

“My great grandmother can finally rest in peace,” she told Carmon with tears in her eyes.

Espiransa would be proud to know her testimony served to bring justice.

The story had had repercussions beyond the academic.

Several historians had begun investigating other similar cases of power abuse by 19th century aristocratic families.

Maria Carman’s case had opened a national conversation about how official history had often hidden injustices committed by privileged classes.

Carmen had received offers from international universities to continue her research, but had decided to stay in New York to establish a foundation dedicated to investigating historical cases of unsolved disappearances.

Maria Carmon can’t be the only person whose story has been erased by power, Carmon had declared in an interview for National Geographic.

The Dgera type had revealed much more than a simple love story.

It had exposed a system of oppression that had allowed powerful families to act as judges, juries, and executioners when their interests were threatened.

On a spring afternoon, Carmen was in her office examining the Dgerayype once more when she noticed something she had overlooked during months of investigation.

In the background of the photograph, barely visible in a corner, was a small inscription engraved in the copper plate, “Forever J&MC.

” Carmen smiled upon realizing that Haqin and Maria Carman had found a way to be together for eternity.

Their love, captured in that 1847 photograph, had survived not only death, but also attempts to erase it from history.

The Darotype had fulfilled its mission.

After more than 170 years of silence, it had shouted the truth to the world.

Mendoza Carvajal and Maria Carmen Delgado Eva had demonstrated that true love is more powerful than any social convention and that truth though late always finds a way to emerge.

The story had become a symbol of historical justice and had inspired a new generation of researchers to question official narratives and seek the voices that had been silenced by power.

Carmon had established an important precedent that victims of the past deserved to be remembered and that no crime, however old, should go unpunished.

Museums around the world had requested loans of the dgerot type for their exhibitions on social history and human rights.

The photograph had become a universal symbol of love that transcends social barriers and of the courage necessary to seek truth.

Carmen carefully closed the case file knowing she had completed not just an academic investigation but a mission of historical justice.

The dgereroype of the mysterious couple from 1847 had finally revealed its secret.

And that secret had forever changed how we understand the power of love and the importance of preserving the memory of those who were unjustly silenced by history.

Maria Carmon and Hain separated in life by social conventions and family cruelty had found in death the justice and recognition that had been denied them in life.

Their eternal love, captured forever on a silverplated copper plate, would continue inspiring future generations to fight for truth and justice, no matter how much time had passed.

News

🔥 Miami Archbishop Breaks Ranks After Pope Leo XIV’s New Document Drops—His Measured Words Mask Alarm, Unease, and a Rift Few Expected as the Church Braces for Fallout 😱 In a cool yet cutting narrator tone, the reaction is framed as diplomatic on the surface but loaded underneath, with carefully chosen phrases, strategic pauses, and the unmistakable sense that this document landed harder in Miami than Rome anticipated 👇

The Shattering Silence Father Gabriel stood at the altar, the flickering candles casting shadows that danced like restless spirits. The…

🕯️ Pope Leo XIV Highlights the Closing of the Holy Door—A Final Gesture That Felt Less Like Ceremony and More Like a Verdict as Silence Thickened and the Vatican Froze 😱 In a hushed, dramatic cadence, the narrator dwells on the Pope’s deliberate emphasis, the stone sealing shut, and the collective inhale of clergy who sensed the spotlight wasn’t on mercy anymore but on what comes after it 👇

The Last Embrace of the Holy Door In the heart of Rome, beneath the shadow of St. Peter’s Basilica, a…

🕯️ Pope Leo XIV LIVE: Holy Mass and the Dramatic Closing of the Holy Door on Epiphany 2026—A Sacred Broadcast That Felt More Like a Reckoning as Silence Fell, Eyes Locked, and the Vatican Held Its Breath 😱 In a reverent yet razor-edged cadence, the narrator leans into the unscripted pauses, the weight of ancient stone, and the charged stillness that made viewers wonder whether this was merely ritual—or a deliberate signal that mercy’s season had ended and accountability had begun 👇

The Veil of Deception In the heart of the Vatican, a storm brewed beneath the surface, unseen by the faithful…

🕯️ UNSEEN MOMENTS: Pope Leo XIV Officially Ends Jubilee Year 2025 by Closing the Holy Door—But What Cameras Missed Sparked Chills Through the Vatican and Left Insiders Whispering of a Turning Point for the Church 😱 In a reverent yet razor-edged tone, the narrator hints at a pause that lasted too long, a gesture unscripted, and faces among the clergy that shifted from solemn to stunned as the Holy Door sealed more than a year of mercy, quietly signaling an era ending and another beginning 👇

The Last Door: A Revelation at St.Peter’s Basilica On a day that dawned with an electric tension, Pope Leo XIV…

🔥 “Closest Advisors—or Decorative Witnesses?” Cardinal Brislin’s Blunt Consistory Remark Ignites Vatican Firestorm as Insiders Whisper of Power Hoarded, Advice Ignored, and a Papacy Running on Silence 😱 With a sharp, knowing bite, the narrator leans in on that loaded line about being the Pope’s closest counselors, hinting at a room full of red hats sidelined while decisions sail past them, calendars change overnight, and loyalty is tested by how little you’re told 👇

The Shadows of the Vatican: A Revelation In the heart of the Vatican, where whispers of power and faith intertwine,…

🕯️ A Silent Disappearance in the Vatican: The Sudden Removal of the Pope’s Master of Ceremonies Sparks Whispers of Power Plays, Liturgical Purges, and a Shadow War Behind the Silk Curtains 😱 In a hushed, ominous cadence, the narrator hints at doors closing without explanation, calendars quietly rewritten, and aides exchanging looks as centuries of ritual collide with modern control, suggesting this wasn’t a routine reassignment but a surgical move that says far more about who’s really steering the Church than any homily ever could 👇

The Shadows of the Vatican In the heart of Vatican City, where secrets intertwine with faith, a storm was brewing….

End of content

No more pages to load