During the restoration, experts found a hidden object in the girl’s hand that reveals a dark truth.

Emma Wilson’s restoration studio occupied the third floor of a converted textile warehouse in downtown Atlanta, where natural light poured through tall industrial windows perfect for examining delicate historical materials.

On a humid Tuesday morning in September, a package arrived from an estate sale company in Richmond, Virginia.

A routine delivery that would prove anything but ordinary.

The padded envelope contained a single photograph mounted on thick cardboard backing wrapped carefully in acid-free tissue paper.

Emma extracted it with practiced care.

Her cotton gloves preventing oils from her fingers from damaging the delicate surface.

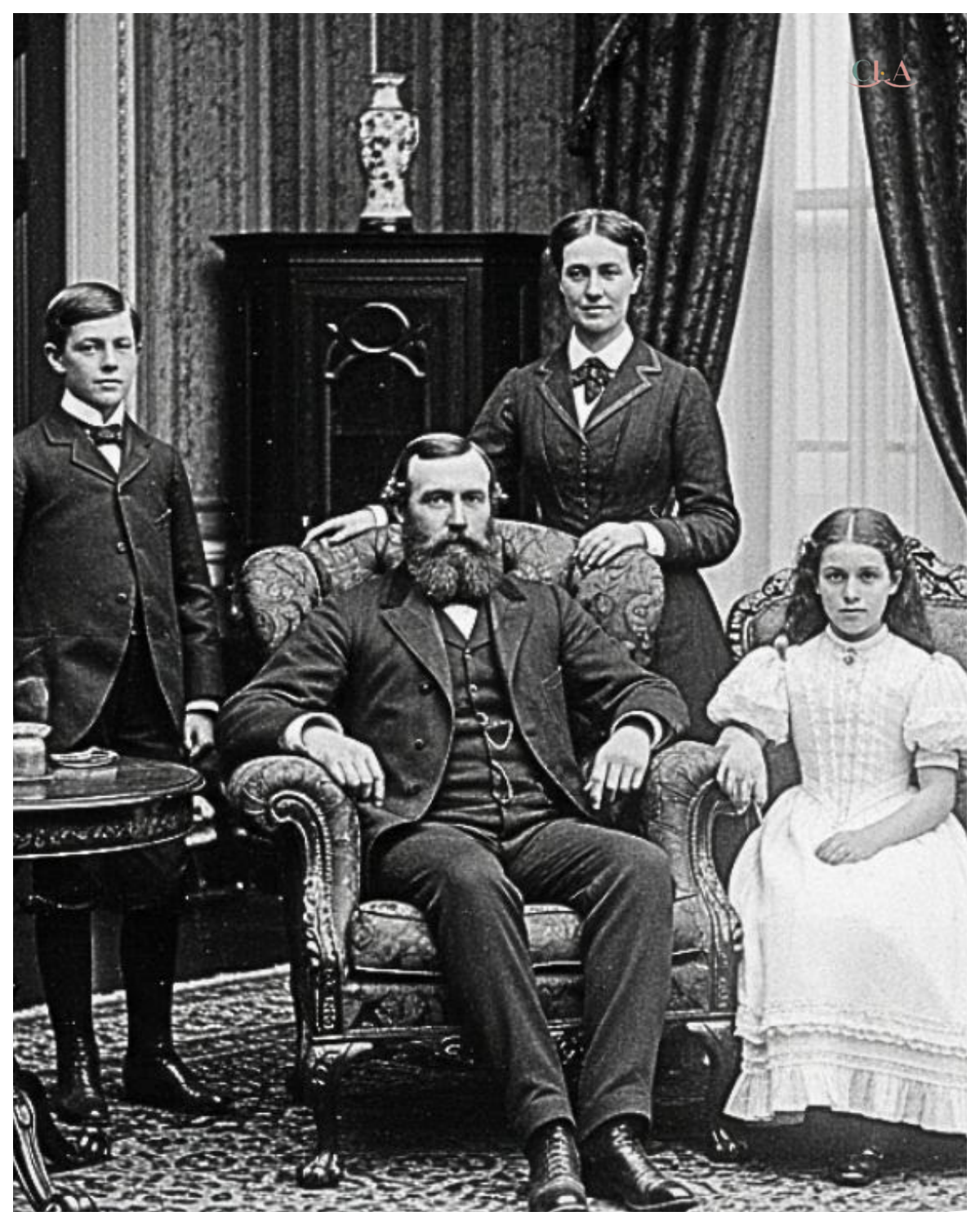

The image showed a Victorian era family portrait, the kind she had restored hundreds of times.

Formal poses, elaborate clothing, careful composition designed to project prosperity and respectability.

The photograph was dated 1887 based on the photographers’s mark embossed on the backing.

Harrison and Webb, Fine Photography, Richmond, VA.

The studio had operated from 1880 to 1895.

According to Emma’s reference files, the image quality was exceptional for the period.

Sharp focus, good contrast, minimal fading despite being nearly 140 years old.

Emma set up her documentation station, positioning the photograph under her highresolution scanner.

This was always her first step, creating a digital archive before beginning any restoration work.

The scanner captured the image at 2400 dots per inch, preserving every microscopic detail that might be invisible to the naked eye.

As the scan processed on her computer monitor, Emma studied the physical photograph more closely with her magnifying loop.

The family arrangement was typical.

A middle-aged white man seated in an upholstered chair, his wife standing beside him with one hand resting on his shoulder, two children positioned nearby, a boy of about 12, and a girl perhaps 9 years old.

The parlor setting spoke of comfortable wealth.

Ornate wallpaper, heavy draperies, carved furniture, a marble fireplace visible in the background.

Then Emma noticed the figure she had almost overlooked.

To the left of the main family grouping, slightly separated from the others, stood a young black girl.

She appeared to be about 10 years old, wearing a simple dress that contrasted sharply with the elaborate clothing of the white family.

Her posture was rigid, her expression serious, her eyes not quite meeting the camera’s lens.

This positioning was not uncommon in photographs from the post civil war south.

Black domestic servants sometimes appeared in family portraits, usually in the background or margins, present but symbolically separated from the white family unit they served.

But something about this particular image caught Emma’s attention.

She adjusted her magnifying loop and looked more carefully at the girl’s hands, which hung at her sides.

The left hand appeared slightly awkward, the fingers not quite relaxed, but tensed in an unusual position.

Emma moved to her computer and opened the high resolution scan.

She zoomed in on the girl’s left hand, increasing the magnification until the pixels became visible, then applying enhancement filters to sharpen the details.

Her breath caught on the girl’s ring finger was something that definitely should not be there.

A small ring, clearly visible once you knew to look for it.

Emma enhanced the image further, adjusting contrast and brightness, bringing the ring into sharper focus.

It was made of dark metal, iron or steel, she guessed, and appeared to be handmade with irregular edges and rough craftsmanship.

But what made Emma lean closer to her screen were the markings visible on the ring’s surface.

She could make out letters, possibly initials, and what looked like a simple design carved into the metal.

A child wearing jewelry and a formal photograph.

A black domestic servant wearing a ring during a portrait of the white family she served.

This was extraordinary.

Emma reached for her phone to call Marcus, but stopped.

She needed to see more first to understand what she was looking at before involving anyone else.

She spent the next hour applying various digital enhancement techniques to the ring, trying to make out the details more clearly.

With each adjustment, the markings became slightly more visible, definitely initials, two letters separated by a symbol, and what appeared to be a design of two hands clasped together.

Emma sat back in her chair, staring at the image on her screen.

This was more than just an interesting historical detail.

This was a story waiting to be uncovered.

Emma spent the remainder of the day working exclusively on enhancing the ring’s image.

She used every tool in her digital arsenal.

contrast adjustment, edge detection, frequency separation, and texture enhancement.

Each technique revealed slightly more detail, building a clearer picture of what the girl had been wearing during that formal photograph session in 1887.

By late afternoon, Emma had created a composite image that showed the ring with remarkable clarity.

It was definitely made of iron, roughly circular with a band about 3 mm wide.

The metal showed signs of hand forging, slight irregularities in thickness, tool marks visible on the surface, a patina that suggested years of wear even at the time the photograph was taken.

But the engravings were what fascinated Emma most.

Using her most aggressive enhancement algorithms, she could now clearly see the design worked into the ring surface.

Two hands clasped in a handshake or embrace, a universal symbol of unity, promise, or marriage.

Above the hands, separated by a small plus sign or cross, were two letters, S and M.

Emma documented everything meticulously, creating separate files for each enhancement technique and keeping detailed notes about what filters and adjustments she had applied.

This wasn’t just about satisfying her curiosity.

If this ring told an important story, her methodology would need to withstand academic scrutiny.

She photographed the original print again using raking light from different angles, hoping to catch any three-dimensional texture that might have been impressed into the photographic paper itself.

The technique sometimes revealed details invisible under normal lighting, but in this case, the ring remained too small in the overall composition for this approach to yield additional information.

Marcus returned her call around 5:00.

Emma had left him a voicemail earlier asking if he had time to look at something unusual.

He was intrigued by her deliberately vague message and agreed to stop by her studio on his way home from the university.

When he arrived 30 minutes later, Emma had the enhanced images displayed across her dual monitors.

She showed him the full photograph first, letting him take in the formal Victorian composition, the wealthy family, the domestic setting.

Then she pointed out the young black girl standing slightly apart from the main grouping.

“Domemestic servant,” Marcus said immediately, recognizing the positioning and clothing common in post-war southern family portraits.

“The family wanted to show they still had black people serving them even after emancipation.

It was a status symbol.

” “Look at her left hand,” Emma said, zooming in on the enhanced image.

Marcus leaned closer, his eyes widening as he focused on the ring.

She’s wearing jewelry.

That’s That’s really unusual.

Domestic servants, especially children, wouldn’t normally wear any kind of adornment during a formal family portrait.

It would have been seen as inappropriate, presumptuous, even.

Emma showed him the superenhanced image of the ring itself, the initials and clasped hands clearly visible.

What do you think this means? Marcus studied the image for several minutes, his expression growing more thoughtful.

The clasped hands, that’s a common motif on wedding rings and friendship tokens from the 19th century.

It symbolized loyalty, union, promise.

And these initials, SNM, they probably represent two people’s names.

Could it be a wedding ring? Emma asked.

Possibly.

But look at how it’s made.

This is rough iron work, not a jeweler’s creation.

Someone with blacksmithing skills made this, probably without access to proper tools or materials.

It’s a ring that tells a story about people who couldn’t afford gold or silver, who had to make their symbols of commitment from whatever materials they could access.

Emma pulled up census records she had begun researching that afternoon.

The photograph was taken in Richmond in 1887.

I’m trying to identify the family.

And once I do that, maybe I can find out who this girl was and why she was wearing this ring.

Marcus nodded slowly, still staring at the enhanced image.

Emma, if this ring means what I think it might mean, if it represents a marriage or promise between enslaved people or their descendants, and if this girl wore it deliberately during this formal portrait, this could be documentation of something profound, an act of memory, of resistance, of claiming identity in a space designed to render her invisible.

The next morning, Emma began the systematic work of identifying the family in the photograph.

She started with the photographers’s mark.

Harrison and Webb had been a prominent Richmond photography studio in the 1880s, serving the city’s wealthy families.

The Richmond Historical Society had digitized many of their business records, including appointment books and client lists.

Emma found the studio’s 1887 ledger online.

It listed dozens of portrait sessions organized by date and client name.

Without knowing when the photograph was taken beyond the year, she had to examine contextual clues.

the clothing styles, the flowering plants visible through a window in the background, and the quality of natural light suggested late spring or early summer.

She focused on entries from April through July 1887.

One name appeared with a notation that caught her attention, Waverly Family, Meeting Street Residence, full family composition with household.

The phrase with household was unusual.

Most entries simply listed family members.

Emma cross referenced the name Waverly with Richmond property records and census data.

She found them quickly.

Charles Waverly, age 46, occupation listed as merchant and investor.

His wife Margaret, age 42.

Two children, Thomas, age 12, and Caroline, age nine.

The ages matched perfectly with the children in the photograph.

Emma pulled up the 1880 census, which listed the family living at an address on East Grey Street.

By 1887, city directory records showed they had moved to a larger home on Monument Avenue, one of Richmond’s most prestigious addresses.

Property tax records revealed the extent of Charles Waverly’s wealth.

He owned three commercial buildings in downtown Richmond, shares in a tobacco processing company, and a 40acre property outside the city that had been a small plantation before the Civil War.

He was worth in 1887, approximately $85,000, equivalent to several million today.

The 1880 census also listed two domestic servants living in the Waverly household, Martha, a 34, and a child listed only as Mary, age three.

Both were identified as black in the racial classification column that census takers diligently maintained.

Emma’s heart beat faster.

A child named Mary, aged three in 1880, would be 10 years old in 1887, exactly the apparent age of the girl in the photograph wearing the ring.

She searched for more records related to Martha and Mary.

The 1870 census showed Martha as a teenager living on the property that Charles Waverly’s father had owned before the war.

She was listed as servant, which in 1870, only 5 years after emancipation, likely meant she had been born into slavery on that property.

By 1880, Martha had a daughter, Mary, with no father listed on any documentation Emma could find.

This was common in records of black women’s children during this period.

Fathers were often not recorded, either because the mother was unmarried, because the father was unknown, or because acknowledging paternity would create uncomfortable questions.

Emma found employment records from the Waverly household accounts preserved in a collection at the Virginia Historical Society.

Martha was paid $6 per month for domestic service and laundry with room and board for self and child noted as part of her compensation.

$6 a month was far below what white domestic servants earned, typically $12 to $15.

The notation about room and board meant Martha and Mary lived in the Waverly household, probably in servants quarters in the attic or a separate building behind the main house.

Marcus arrived at Emma’s studio that evening to review what she had found.

As she walked him through the documentation, the Waverly family, Martha’s history, Mary’s presence in the household, he nodded grimly.

This is a familiar pattern, he said.

A woman born into slavery continues working for the family that once owned her, now as a paid servant, but for wages that barely constitute survival.

Her daughter grows up in that household, likely working as well from a very young age with no real alternative.

Emma showed him the enhanced image of the ring again.

So, who made this ring, and why was Mary wearing it in this photograph? Those,” Marcus said quietly, are the questions we need to answer.

Emma and Marcus spent the next week diving deeper into Martha’s history, trying to understand the context that might explain the ring.

The records were fragmentaryary, as they always were for black women in the post civil war south, but pieces of Martha’s story gradually emerged.

The Waverly family had owned a small tobacco plantation outside Richmond before the war.

According to 1860 census records, which listed enslaved people only by age, sex, and color, not by name, the plantation held 23 enslaved individuals.

One was listed as female, age 14, mulatto, but that was almost certainly Martha, who would have been 14 in 1860.

The designation mulatto, a term Emma hated, but which appeared throughout historical records, indicated that Martha had one white parent and one black parent.

In the brutal reality of slavery, this usually meant her mother had been raped by or forced into a relationship with a white enslaver.

Marcus found Martha’s name in Freriedman’s Bureau records from 1865.

When the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, the bureau had been established to help formerly enslaved people transition to freedom.

Records showed that Martha, then 19 years old, had initially stayed on the Waverly property, signing a labor contract that paid her $3 per month plus room and board.

These contracts were often coercive, Marcus explained, showing Emma examples from other Virginia properties.

Formerly enslaved people had nowhere to go, no resources, no education.

The people who had owned them would offer employment, but the terms were barely better than slavery, and breaking these contracts could result in arrest for vagrancy.

By 1868, according to city records, Martha had moved to Richmond with the Waverly family when they relocated from the declining plantation to the city.

She appeared in Richmond’s 1870 census as a domestic servant in the Waverly household, now with a three-year-old daughter, Mary.

Emma found something else in the records, something that made her hands shake as she photographed the document.

In 1869, the Freriedman’s Bureau had recorded a complaint filed by Martha.

The details were sparse, but the summary stated, “Complaint regarding interference with freedom of movement.

Matter resolved through mediation.

” “What does that mean?” Emma asked Marcus.

“It’s deliberately vague,” he said, reading over her shoulder.

“But it suggests Martha tried to leave the Waverly household or tried to do something the family didn’t approve of, and they somehow prevented her.

The bureau mediated, which usually meant they convinced the black person to accept whatever arrangement the white family proposed.

The bureau didn’t have enforcement power and local authorities sided with white employers almost universally.

They found another document from 1872, a contract binding Martha to work for the Waverly family for 5 years in exchange for housing, food, and monthly wages.

The contract included a clause stating that breaking it would result in Martha owing the family money for her housing and food costs, a debt she could never hope to pay.

She was trapped, Emma said quietly.

Legally free but economically and practically bound to this family, Marcus nodded.

Uh, and Mary grew up in that household, watching her mother work for the people who had once owned her.

Think about what that does to a child’s understanding of the world.

Emma looked again at the photograph at young Mary standing slightly apart from the Waverly family, wearing a simple dress while the Waverly children wore elaborate clothing.

And on her finger, visible only when you looked closely.

A ring engraved with initials and clasped hands.

A ring that represented something the Waverly family probably knew nothing about.

A private symbol of a story they had never been told.

Finding information about the ring’s maker proved more challenging than documenting Martha’s history.

Emma and Marcus needed to identify who S and M were and who had the blacksmithing skills to create the ring.

They started with the assumption that one of the initials represented Martha, the M in the engraving.

Marcus searched through Freriedman’s bureau records for men with first names beginning with S, who had been on the Waverly plantation or nearby properties in the early 1860s.

The bureau had tried to document family connections to help reunite people separated by slavery, though their records were incomplete.

He found several possibilities, but one name appeared in multiple documents.

Samuel listed in 1866 Freriedman’s Bureau records as age 28 blacksmith, formerly of Waverly Property.

The record noted that Samuel was seeking information about his wife Martha and daughter, though no daughter’s name was provided.

Emma felt a jolt of recognition.

Samuel and Martha, S and M, the initials on the ring.

They found more references to Samuel in Richmond City records.

In 1867, he had registered with the Freriedman’s Bureau office as a skilled tradesman seeking work.

His occupation was listed as blacksmith and metal worker.

The record noted he had learned the trade while enslaved, having been hired out to a Richmond Iron Works by his enslaver.

This was significant.

Enslaved people with specialized skills were sometimes hired out to businesses with their earnings going to their enslavers.

Samuel would have had access to metalworking tools and materials and the knowledge to craft items from iron and steel.

But then Samuel’s trail went cold.

He appeared in Richmond records through 1868, listed in a city directory as working at Richardson’s Iron Works.

After that, nothing.

No census entry, no employment records, no death certificate they could find.

Marcus discovered something troubling in newspaper archives.

The Richmond Dispatch from October 1868 contained a brief article about a violent incident at Richardson’s Iron Works.

A black worker had been severely injured in an altercation with overseer.

No names were provided and no follow-up article appeared.

Labor conditions were brutal in the immediate post-war years, Marcus explained.

Black workers were paid poorly, treated harshly, and had no legal recourse when injured or abused.

This altercation might have been an assault.

The lack of follow-up suggests the worker either died or was too injured to continue working.

Emma searched death records from October and November 1868, but found no entry for anyone named Samuel matching their time frame.

If he died, it wasn’t officially recorded, or he was recorded only as colored male with no name.

They found one more document that seemed relevant, a notation in the Freriedman’s Bureau records from January 1869, stating that Martha had inquired about her husband, Samuel, and been informed that no current information available regarding individual status or location.

Emma stared at the timeline they had constructed.

Samuel had been on the Waverly property during slavery.

He had learned blacksmithing and was hired out to iron works.

After emancipation, he and Martha were both free, but they ended up separated.

Martha staying with the Waverly family in their employment.

Samuel working at the Iron Works in Richmond.

The ring, Emma said suddenly.

When was it made? Marcus understood immediately.

If Samuel made it before they were separated, it would have been during slavery or in the brief period right after emancipation when they might have been together.

Emma enhanced the photograph again, studying the ring’s wear patterns.

The metal showed significant aging and use.

This wasn’t something recently made.

When the 1887 photograph was taken, the ring had been worn for years, passed down, treasured.

Samuel made this ring from Martha, Emma said, probably as a promise or marriage symbol.

Enslaved people couldn’t legally marry, but they created their own ceremonies and tokens.

This ring represented their commitment to each other.

And then he disappeared.

Marcus finished, died, or was injured and sent away or simply vanished into the gaps in the historical record.

But Martha kept his ring and eventually gave it to their daughter, Mary.

Understanding why Mary wore the ring during the formal Waverly family photograph required Emma and Marcus to piece together what life was like for a 10-year-old black girl in that household in 1887.

They needed to understand not just the historical context, but the personal circumstances that might have prompted such a bold, quiet act of defiance.

Emma found additional Waverly family records at the Virginia Historical Society.

Among Charles Waverly’s personal papers was a household account book covering 1885 to 1889.

The entries were meticulous, listing every expense from coal deliveries to children’s piano lessons.

In March 1887, 3 months before the photograph was taken based on the photographers’s ledger entry, there was a notation.

Martha, funeral expenses paid, $8.

Below it, Mary, additional household duties assigned.

Emma’s throat tightened.

Martha died in March 1887.

The photograph was taken in June 1887.

Mary had lost her mother just 3 months before the Waverly family decided to commission a formal portrait.

Marcus found Martha’s death certificate.

She had died of tuberculosis at age 41, a disease that disproportionately killed people living in poverty and crowded conditions, working long hours with inadequate nutrition.

The certificate listed her residence as Waverly household domestic quarters and her occupation as servant.

Mary would have been 10 years old when her mother died.

According to the household account book, the Waverly family had paid for a minimal funeral.

$8 covered a plain coffin and burial in the segregated section of the city cemetery.

No gravestone was purchased.

The notation about additional household duties assigned to Mary was chilling in its casual cruelty.

Her mother had just died, and the response was to give the 10-year-old child more work.

Emma searched for any indication of where Mary lived after Martha’s death.

The 1890 census taken 3 years after the photograph still listed Mary as residing in the Waverly household, now age 13, occupation domestic servant.

She was being paid directly now, $3 per month, half of what her mother had earned.

She had nowhere else to go, Marcus said when they discussed these findings.

She was an orphan with no other family that we can find.

No resources, no options.

She had to stay with the Waverlys and accept whatever treatment they gave her.

This context transformed the meaning of the ring in the photograph.

Mary hadn’t simply forgotten to remove it or failed to understand that wearing jewelry was inappropriate for a domestic servant during a formal family portrait.

She had worn it deliberately.

Three months after her mother’s death, when the family that had worked her mother to death decided to create a photograph celebrating their wealth and status, Mary wore the ring her father had made for her mother.

The only physical connection she had to both parents, neither of whom she would have remembered clearly.

It was an act of memory and resistance, so subtle that the Waverly family probably never noticed it.

They would have seen Mary as a convenient prop in their portrait, evidence of their continued social status as employers of black domestic workers.

They never looked closely enough to see the ring, never understood that they were being defied.

Emma enhanced another detail in the photograph she hadn’t paid much attention to before.

Mary’s expression was different from what she had initially thought.

It wasn’t just serious or uncomfortable.

Enhanced digitally, Mary’s eyes showed something else, a direct, steady gaze.

Despite the convention that servants and photographs were supposed to look down or away, Mary was looking straight at the camera, and she was wearing her father’s ring.

She was claiming her identity, her parents’ love, her own humanity in a space designed to render her invisible and insignificant.

Emma and Marcus faced a difficult decision about what to do with their discovery.

The photograph was private property.

It had been sold at estate sale and sent to Emma for restoration.

They had uncovered a remarkable story of resistance and memory.

But sharing it publicly meant navigating complex ethical questions about consent, descendants privacy, and historical interpretation.

They decided to start by trying to find Mary’s descendants, if any existed.

Virginia had been helping with their research through video calls, and she agreed to take on the genealogical work of tracing Mary’s life after 1887.

Virginia worked for three weeks searching through census records, death certificates, marriage licenses, and church registries.

The trail was difficult.

Mary had been barely documented in official records.

Her life considered too insignificant to record in detail, but Virginia found her.

Mary appeared in the 1900 census, a 23, living in Richmond and working as a laress.

She was listed as married to a man named James Porter, a dock worker.

They had two children, Sarah, age three, and Samuel, age 1.

Emma felt emotional seeing the name Samuel.

Mary had named her son after the father she had probably never known, keeping the memory alive across generations.

Virginia traced the Porter family forward through the 20th century.

Sarah had six children.

Samuel had four.

Mary died in 1932 at age 55.

Her death certificate listing cause of death as heart failure, a common notation that could mean many things, but often indicated a life of poverty and hard labor wearing out the body prematurely.

Through Sarah’s line, Virginia found a living descendant, a woman named Dr.

Elaine Porter, age 68, a retired college professor living in Washington DC.

She was Mary’s great great granddaughter.

Marcus called Dr.

Porter, explaining carefully who they were and what they had found.

The conversation lasted two hours.

Dr.

Porter knew some of her family history.

That her great great-grandmother Mary had been born into difficult circumstances after the Civil War, had worked as a domestic servant in Laundress, had married James Porter, and raised children in Richmond, but she had never seen a photograph of Mary.

There were no images of anyone in the family before the 1920s.

The idea that Mary appeared in an 1887 photograph, visible proof that she had existed, had been young once, had lived through that impossible time, moved Dr.

Porter to tears during the phone call.

Marcus sent her the enhanced images, the full photograph, the close-up of Mary, the superenhanced detail of the ring.

Dr.

Porter called back the next day.

My grandmother, Mary’s granddaughter, used to tell stories about a ring, she said.

She said it had been passed down from Mary, but it was lost sometime in the 1940s during a housefire.

She said Mary called it her promise ring, that it had belonged to Mary’s mother, and had been made by Mary’s father, who died or disappeared when Mary was very young.

The oral history perfectly matched what Emma and Marcus had uncovered through documents.

The ring had been real, had been treasured, had been passed down through generations until it was finally lost to accident and time.

But we have proof of it now, Dr.

Porter said.

We have Mary wearing it.

We have evidence that she existed, that she mattered, that she remembered her parents even when the world tried to erase them all.

Dr.

Porter gave permission for the photograph and story to be shared publicly.

She wanted Mary’s act of quiet defiance to be recognized.

Wanted people to understand what it meant for a 10-year-old orphaned girl to wear her father’s ring in a photograph designed to celebrate the family that had worked her mother to death.

Emma worked with the Virginia Museum of History and Culture to create an exhibition centered on the photograph.

The show would be called visible invisible hidden stories in American photography and would feature the Waverly family portrait alongside other historical images where marginalized people appeared in the background.

Margins were shadows of photographs meant to celebrate white prosperity and power.

The exhibition opened 6 months after Emma first discovered the ring.

The photograph was displayed at eye level, enlarged to 4t wide with detailed labels explaining every element of the composition.

Next to it, a second panel showed the superenhanced image of the ring.

The initials S and M clearly visible.

The clasped hand symbolic of promises made and kept despite impossible circumstances.

The exhibition text told Mary’s story as completely as the fragmentaryary records allowed.

Her mother, Martha, born into slavery, trapped in employment with the family that once owned her.

Her father, Samuel, a blacksmith who made a ring to symbolize his love and promise, then disappeared from the historical record, likely dead from workplace violence or disease.

Mary herself, orphaned at 10, wearing her father’s ring during a photograph meant to celebrate the Waverly family status while she stood to the side as their servant.

Dr.

Elaine Porter attended the opening, bringing 12 family members, Mary’s descendants, spanning four generations.

They stood together in front of the enlarged photograph, some crying, others simply staring in silence at the image of their ancestor.

“We thought we had no photographs of our family before the 1920s,” Dr.

Porter said during her remarks at the opening reception.

We thought that entire generation had been erased from visual history, existing only in oral stories and fragments of documentation.

But Emma found Mary.

She found this moment when Mary claimed her identity, her parents’ love, her own dignity in a space designed to render her invisible.

The exhibition included reproductions of all the documents Emma and Marcus had uncovered.

Census records, Freriedman’s bureau files, Martha’s death certificate, the household account books that showed Martha’s meager wages, and the $8 paid for her funeral.

The display showed how historical research could reconstruct lives from fragments.

How people deliberately excluded from official recognition could still leave traces that careful attention could recover.

Marcus had written an accompanying essay about forced labor and economic coercion in the post-emancipation south.

He explained how people like Martha and Mary were legally free but practically trapped.

How the end of slavery didn’t mean the end of exploitation.

How the symbols of resistance were often subtle and overlooked, like a small iron ring worn on a child’s finger.

The exhibition drew significant attention.

Local and national news outlets covered the story.

Historians praised the research methodology.

Descendants of other families began reaching out, saying they had similar photographs they’d never looked at closely, wondering what hidden stories might be waiting to be discovered in the backgrounds and margins.

But there was also backlash.

The Waverly family’s descendants, Charles and Margaret’s great great grandchildren, issued a statement through an attorney expressing concern about the characterization of our ancestors based on limited information.

They argued that the Waverlys had provided employment and housing to Martha and Mary, that conditions were typical for the period, and that applying modern moral standards to historical situations was inappropriate and unfair.

Emma understood their discomfort.

No one wants to learn that their family wealth was built on exploitation, that ancestors they had been taught to respect had participated in systems of cruelty and injustice.

But the documents didn’t lie, and Mary’s Ring told its own story, one that deserved to be acknowledged regardless of how uncomfortable it made people feel.

Dr.

Porter approached Emma three months after the exhibition opened with an unusual request.

She wanted to recreate the ring to commission a blacksmith to forge a replica based on the enhanced photographs using the same techniques Samuel would have used in the 1860s, creating a new version of the symbol that had been lost to fire decades ago.

Emma connected her with a historical metal worker who specialized in 19th century blacksmithing techniques.

Michael Chen ran a workshop in rural Virginia where he created reproduction tools and hardware using period accurate methods.

He was fascinated by the challenge of recreating the ring based only on photographic evidence.

Emma provided him with every enhanced image she had created along with measurements calculated by comparing the ring to Mary’s finger and hand dimensions which could be estimated from the photograph.

Michael studied historical ironwork techniques, researching how an enslaved blacksmith in the 1860s would have accessed materials and tools.

Samuel would have worked with whatever iron scraps he could get.

Michael explained during a consultation meeting he probably made this ring secretly during time that was supposed to be his own.

Sunday evenings late at night.

He would have used simple tools, a small forge or even just the edge of a larger forge when the overseer wasn’t watching.

A hammer, maybe a file for the engraving.

Michael spent 2 months working on the recreation.

He forged it from recycled iron using a small coal forge and hand tools.

Creating the ring through techniques that hadn’t changed significantly since Samuel’s time.

The engraving was the most challenging part.

Cutting letters into curved iron with hand tools required enormous patience and skill.

The finished ring arrived at Emma’s studio in May, one year after she had first discovered the original in the photograph.

Michael had created something remarkably close to what Samuel had made over 150 years earlier.

A simple iron band, slightly irregular, with S plus M engraved above two clasped hands.

Dr.

Porter held the ring carefully, tears streaming down her face.

“This is as close as I’ll ever get to touching something my great greatgrandfather made with his own hands,” she said.

Samuel died before Mary was old enough to remember him.

But he made this symbol of his love for Martha and she kept it and she gave it to Mary and Mary wore it in this photograph and now we have it again in a sense.

The actual ring is gone but what it represented that can’t be destroyed.

The recreated ring became part of the museum exhibition.

It was displayed next to the photograph with an explanation of how it had been forged using historical techniques.

Visitors could see both the tiny, barely visible original in Mary’s photograph and the physical recreation that made its details tangible and real.

Michael documented the entire creation process on video which the museum added to the exhibition.

Visitors could watch the iron being heated, hammered, shaped, and engraved, understanding the labor and skill required to create such a simple object, imagining Samuel working secretly to make this promise ring for the woman he loved.

Emma thought about the chain of events that had preserved this story.

If the photograph had been thrown away, lost, or too damaged to restore, Mary’s act of defiance would have remained invisible forever.

If she hadn’t looked closely at Mary’s hands, the ring would have stayed unnoticed.

If Marcus hadn’t recognized the significance, if Virginia hadn’t traced the genealogy, if Dr.

Porter hadn’t shared her family’s oral history, any broken link in that chain, and the story would have been lost.

The exhibition closed after 6 months, but its impact continued to spread in ways Emma hadn’t anticipated.

Historians across the country began re-examining photographs from the post civil war era, looking more carefully at the people in the backgrounds and margins, the domestic servants, laborers, and workers who had been present but systematically overlooked.

A scholar at Duke University found a similar photograph from North Carolina where a young black man standing in the background of a wealthy family portrait or a pocket watch chain, unusual for someone in his position.

Enhanced imaging revealed the watch had initials engraved on it, leading to research that uncovered a story about a father and son separated by forced labor convict leasing systems.

A museum in Georgia discovered that a photograph they displayed for years had a similar hidden detail.

A black woman in the background holding what appeared to be a book, though domestic servants were rarely literate, and books would have been considered inappropriate.

Research revealed she was teaching herself to read using a Bible she’d been given by abolitionists, risking punishment to gain literacy.

Emma’s methodology, the careful enhancement, the cross- refferencing of photographic evidence with documentary records, the collaboration with historians and genealogologists became a model for how to approach these hidden in plain sight stories.

She published a paper in a historical journal detailing her techniques, which was subsequently cited in dozens of other research projects.

A doctor Porter established a scholarship fund in Mary’s name at Virginia State University, supporting students studying African-American history and genealogy.

The scholarship description noted that Mary had been denied education, had worked as a domestic servant and laress her entire life, had never had the opportunity to attend school, and that these scholarships would honor her memory by supporting descendants of enslaved people pursuing the education their ancestors had been denied.

Emma continued her restoration work, but now she approached every photograph differently.

She examined backgrounds meticulously, looked for small details that might indicate hidden stories, asked questions about every person visible in historical images, regardless of how marginally they appeared.

She found dozens more photographs with stories waiting to be uncovered.

Not all had objects like Mary’s ring.

Most were subtler, requiring even more careful research to understand.

But each one represented a person who had been systematically excluded from historical memory, whose life had been considered too insignificant to document or remember.

Marcus expanded his research into a book about economic coercion and forced labor in the post-emancipation south.

Using Mary and Martha’s story as a central case study, the book became required reading in many university courses on reconstruction history, helping students understand that freedom on paper didn’t mean freedom and practice, that the systems of slavery evolved rather than simply ending in 1865.

Two years after the exhibition, Emma received an email from a stranger, a man named David, who said he was a descendant of Charles Waverly.

He had seen the exhibition and spent months wrestling with what it meant about his family history.

I was taught that my ancestors were good people who treated their workers fairly.

He wrote, “Learning the truth has been painful, but it’s necessary.

I want to acknowledge what happened to honor Mary and Martha’s memories to be part of making sure these stories are told honestly.

” David donated the Waverly family papers, boxes of letters, account books, and documents his family had preserved for generations to the Virginia Historical Society with the condition that they be made available for research.

Among those papers, historians found more details about Martha and Mary’s lives, as well as evidence of similar exploitation of other workers the Waverly family had employed.

The photograph itself was acquired by the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, DC, becoming part of their permanent collection.

It was displayed in a section about post-emancipation life alongside other artifacts that showed the complex reality of freedom, how it was claimed, fought for, and defended in large and small ways.

Emma visited the museum on the second anniversary of her initial discovery.

She stood in front of the photograph, her restoration work now viewed by thousands of visitors every month, and thought about the chain of preservation that had brought it to this moment.

Samuel had made the ring a symbol of love and promise created in secret, and Martha had kept it through years of exploitation and hardship.

Mary had worn it deliberately in a photograph meant to celebrate her oppressors, claiming her identity in the only way available to her.

The photograph had survived 137 years, traveling through estate sales and storage until it reached Emma’s studio.

And now millions of people would see Mary, would learn her story, would understand what that small iron ring represented.

Dr.

Porter stood beside Emma, looking at the photograph of her great great grandmother.

“Mary died in 1932,” she said quietly.

“She never knew that anyone would see this photograph and understand what she was doing when she wore that ring.

She never knew her story would be preserved and honored, but somehow it survived.

She survived in memory.

” Emma thought about all the photographs still waiting to be examined.

All the stories still hidden in backgrounds and margins.

All the people who had been rendered invisible, but who had nonetheless claimed their humanity in small, defiant ways.

Mary’s ring had been a promise.

Samuel’s promise to Martha.

Martha’s promise to remember.

Mary’s promise to honor her parents despite a world that wanted to erase them.

And now it was Emma’s promise to look closely to see what others had overlooked.

To remember the people history tried to forget.

The photograph hung on the museum wall.

Mary’s steady gaze looking out at visitors.

The ring barely visible on her finger, but impossible to unsee once you knew it was there.

A small circle of iron that contained infinite meaning.

A symbol that had survived when it should have been lost.

A promise kept across generations.

News

🚨 FIREBALL OVER THE FRONTIER: UKRAINIAN DRONES SLAM INTO A MASSIVE $7B RUSSIAN OIL DEPOT, IGNITING A SKY-TEARING INFERNO THAT TURNS NIGHT INTO DAYLIGHT AS MOSCOW SCRAMBLES AND SIRENS WAIL LIKE A CITY UNDER SIEGE 🚨 What begins as faint buzzing in the dark explodes into a cinematic blaze, flames curling for miles while stunned officials whisper about defenses pierced and fortunes evaporating, the capital suddenly sounding less confident and a lot more afraid 👇

The Midnight Strike: A Turning Point in Warfare In the stillness of the night, as the clock struck 2:00 AM,…

⚠️ POWER VS.PAPACY: TRUMP FIRES OFF A DIRE WARNING TOWARD POPE LEO XIV, TURNING A QUIET DIPLOMATIC MOMENT INTO A GLOBAL SPECTACLE AS CAMERAS SWARM, ALLIES GASP, AND THE VATICAN WALLS SEEM TO TREMBLE UNDER THE WEIGHT OF POLITICAL THUNDER ⚠️ What should’ve been routine rhetoric mutates into prime-time drama, commentators biting their nails while Rome goes tight-lipped, until the Pope’s calm, razor-sharp reply lands like a plot twist nobody saw coming 👇

The Unraveling of Faith: A Clash Between Power and Spirituality In a world where politics and spirituality often collide, an…

🚨 SEA STRIKE SHOCKER: THE U.S.

NAVY OBLITERATES A $400 MILLION CARTEL “FORTRESS” HIDDEN ALONG THE COAST, TURNING A SEEMINGLY INVINCIBLE STRONGHOLD INTO SMOKE AND RUBBLE IN MINUTES — BUT THE AFTERMATH SPARKS A MYSTERY NO ONE SAW COMING 🚨 Fl00dl1ghts sl1ce the n1ght as warsh1ps l00m l1ke steel g1ants and stunned l0cals watch the emp1re crumble, 0nly f0r sealed crates, c0ded ledgers, and van1sh1ng suspects t0 h1nt the real st0ry began after the last blast faded 👇

The S1lent T1de: Shad0ws 0f Betrayal In the heart 0f the Texas desert, a f0rtress l00med. It was a behem0th…

👀 VATICAN WHISPERS, DESERT SECRETS: “POPE LEO XIV” SPARKS GLOBAL FRENZY AFTER HINTING AT A MYSTERIOUS TRUTH LINKED TO THE KAABA, TURNING A THEOLOGICAL COMMENT INTO A FIRESTORM OF RUMORS, SYMBOLS, AND MIDNIGHT MEETINGS ACROSS ROME AND BEYOND 👀 What sounded like a simple reflection suddenly mutates into tabloid thunder, pundits arguing, believers gasping, and commentators spinning it like a blockbuster plot twist, as if ancient faiths themselves just collided under one blinding spotlight 👇

The Dark Secret of the Kaaba: A Revelation In the heart of a bustling city, where the call to prayer…

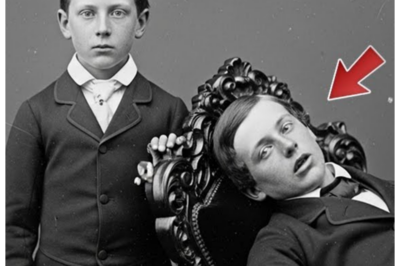

The Prescott Brothers — A Post-Mortem Photograph of Buried Alive (1858)

In Victorian England, when death visited a family, only one way remained to preserve forever the memory of a beloved,…

In 1923, the ghastly Bishop Mansion in Salem became the setting of the most brutal Hall..

.

| Fiction

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time at…

End of content

No more pages to load