During the restoration, experts found a hidden detail in the slave girl’s clothing no one saw before.

Dr.Sarah Chen carefully positioned the dgerotype under the digital microscope, her breath shallow with concentration.

The image before her was haunting.

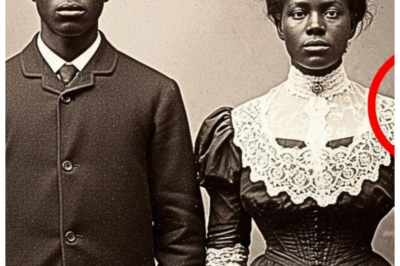

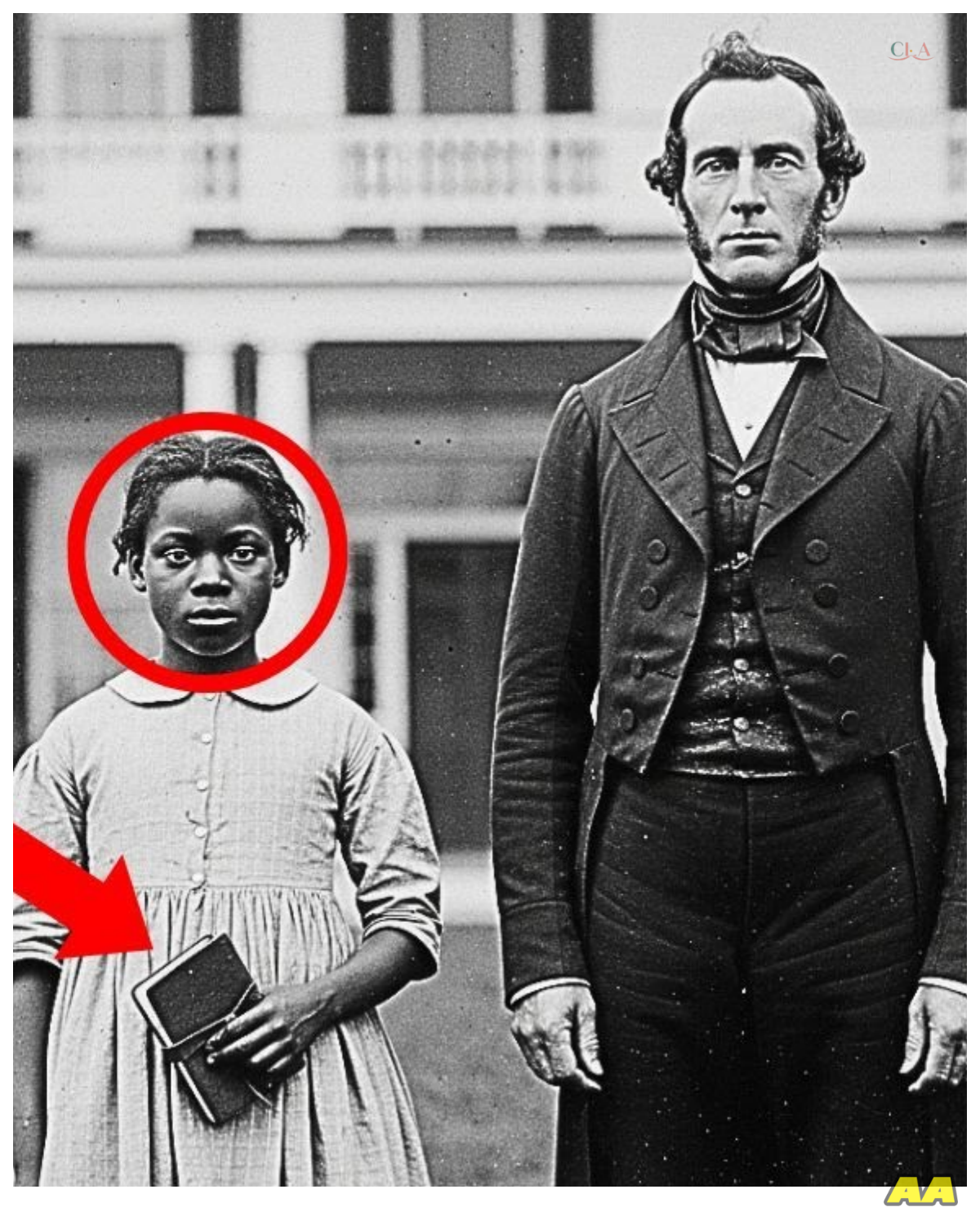

A young black girl, no more than 12, standing rigid beside a well-dressed white man in front of a columned mansion.

New Orleans, 1858.

The plate had arrived at the Smithsonian Conservation Lab 3 weeks ago, donated by an estate in Baton Rouge, and Sarah had been tasked with its restoration and authentication.

The dgeray type was remarkably preserved.

Its silver surface still reflecting light after 166 years.

But something about the girl’s expression unsettled Sarah.

While most enslaved people photographed in that era showed blank, emotionless faces, a defense mechanism against dehumanization, this girl’s eyes held something different.

Not defiance exactly, but intention.

Purpose.

Sarah adjusted the microscope’s magnification, focusing on the girl’s clothing.

The dress was simple.

coarse cotton typical of enslaved children with a crude collar and long sleeves despite what appeared to be summer light in the photograph.

As she scanned the fabric’s texture, looking for damage that might need stabilization, something caught her eye.

There along the left sleeve, barely visible even at 40 times magnification or tiny marks.

At first, Sarah thought they were stains or deterioration of the silver emulsion, but as she adjusted the angle of the light, her heart began to race.

They weren’t random.

They were deliberate letters, numbers.

She leaned back, blinking hard, then looked again.

The marks were microscopically small, stitched into the fabric itself with thread so fine it was nearly invisible.

Sarah’s hands trembled as she reached for her documentation camera.

She had restored hundreds of 19th century photographs, but she had never seen anything like this.

The numbers were clear now, coordinates, latitude and longitude, painstakingly embroidered into the sleeve of a child who had no voice, no rights, no recorded name in any archive Sarah had yet found.

The girl had left a message hidden in plain sight for 166 years.

Sarah picked up her phone, her mind racing.

Whatever those coordinates pointed to, someone had wanted it found.

By morning, Sarah had barely slept.

She’d spent the night cross referencing the coordinates 2995 and 111 Nuz 071 with historical maps of Louisiana.

They pointed to a location roughly 30 mi northwest of New Orleans in what would have been dense swamp land in 1858.

Today it was part of a protected wildlife preserve near Lake Poner train.

She arrived at the lab before dawn bringing the dgeray type to the main conservation theater where senior staff could examine her findings.

Dr.

Marcus Williams, the department head, arrived at 7.

He was a meticulous man in his 60s who had spent four decades authenticating historical photographs and he did not embrace wild theories lightly.

“Show me,” he said simply, settling behind the microscope.

Sarah guided him through her process, explaining how she discovered the embroidery while examining fabric deterioration.

Marcus said nothing for several minutes, adjusting magnification, changing light angles, even pulling out a jeweler’s loop for closer inspection.

Finally, he sat back.

The thread is period appropriate.

Cotton, not synthetic.

The stitching technique is consistent with mid-9th century needle work.

He paused, removing his glasses to clean them.

A nervous habit, Sarah recognized.

But the precision required to create numbers this small, this accurately with the tools available to an enslaved child.

I know, Sarah interrupted.

It should be impossible.

Yet here it is.

Marcus stood, pacing to the window overlooking the National Mall.

Have you identified the girl or the man beside her? Sarah pulled up her research file on the lab’s main screen.

The estate that donated the dgeray type included some documentation.

The man is Nathaniel Duchamp, owner of Bel Rave Plantation about 15 miles up river from New Orleans.

Successful sugar operation.

He died in 1859, just a year after this photograph.

And the girl, nothing.

She’s listed in the donation papers only as enslaved child unidentified.

I’ve been through Bel Rev’s surviving records at the Louisiana State Archives.

Birth registers, sale documents, everything.

Children that young were rarely named in official records unless they were sold.

Marcus returned to the microscope, staring at the girl’s face.

She wanted someone to find this.

The question is why? The Louisiana State Archives in Baton Rouge were housed in a modern building that contrasted sharply with the history it contained.

Sarah had made the three-hour drive from Washington DC with a single mission.

find any record of what happened at Bel Rave Plantation between 1858 and 1859.

The archivist, an elderly woman named Mrs.

Beatatric Tibido, had prepared several boxes of materials based on Sarah’s phone call.

Bel Rev was prosperous until Nathaniel Duchamp’s death, she explained, leading Sarah to a research room.

After that, the property changed hands multiple times.

Most of the plantation records were lost in a fire in 1891.

Sarah’s heart sank.

Most, but not all.

There are fragments, some correspondents, a partial ledger from 1858.

And this Mrs.

Tibido placed a leatherbound journal on the table.

Duchamp’s personal diary donated by a distant relative in 1963.

No one’s paid much attention to it.

Plantation owner’s diaries from that period are fairly common and frankly often disturbing to read.

Sarah opened the journal carefully.

The pages were yellowed but intact, filled with Duchamp’s cramped handwriting.

Most entries were mundane.

Weather conditions, sugar prices, social visits.

Then dated August 3rd, 1858, just two weeks before the Dgeray types date stamp.

She found something different.

The girl saw.

I’m certain of it.

She was in the barn when I returned with the documents.

Her eyes too intelligent, too aware.

I cannot risk her speaking, though who would believe a slave child.

Still, I watch her.

She works in the house now, where I can see her always.

Sarah’s pulse quickened.

She photographed the page, then continued reading.

The next relevant entry was August 17th, 1858.

The date on the Dgerayype.

had our portrait made today as planned.

The photographer from New Orleans came at dawn.

I stood with the girl deliberately.

Let there be record of her presence here should questions arise later.

Though I have been careful, one can never be too cautious.

The matter is buried and shall remain so.

Mrs.

Tibido appeared at Sarah’s shoulder, reading over her glasses.

“What matter?” she whispered.

“I don’t know,” Sarah said, “but I think this girl tried to tell us.

” Back in Washington, Sarah assembled a small team.

Marcus Williams brought in Dr.

James Foster, a historian specializing in antibbellum, Louisiana, and Detective Robert Chen, Sarah’s brother, who had taken leave from the DC Metropolitan Police to help with what was no longer just historical research.

They gathered in the conservation lab’s conference room, the dgerite projected on a large screen.

The girl’s face, magnified 10 ft tall, seemed to watch them.

“I’ve been through every newspaper archive from New Orleans in 1858 and 1859,” James said, spreading printouts across the table.

There was a significant unsolved crime during that period.

On July 28th, 1858, a federal marshall named Thomas Bowmont disappeared while investigating illegal slave trading operations in the Louisiana Bayus, Robert leaned forward.

Illegal? Slavery was legal.

The international slave trade had been banned since 1808, James explained.

But smuggling continued, especially through Louisiana’s waterways.

Bumont had been building a case against several prominent planters, including, he paused significantly, Nathaniel Duchamp.

Sarah felt pieces clicking into place.

Duchamp killed him.

There’s no proof, James cautioned.

Bumont simply vanished.

His investigation died with him.

But look at this.

He pulled out another newspaper clipping dated March 1859.

Duchamp himself died less than a year later.

The death certificate lists cause as sudden illness, but there were rumors.

Some said guilt drove him mad.

Others suggested poison, that perhaps someone on his plantation had taken justice into their own hands.

Marcus studied the timeline on the whiteboard Sarah had created.

So, we have July 28th, Bumont disappears.

August 3rd, Duchamp writes that the girl saw something.

August 17th, the Dgerayype is made with coordinates hidden in the girl’s clothing.

March 1859, Duchamp dies mysteriously.

The coordinates, Robert said.

They have to point to where Duchamp hid evidence of Bowmont’s murder.

Sarah pulled up a modern satellite map of the coordinates.

Dense wetland thick with cypress and undergrowth now protected federal land.

After 166 years, is there any chance something could still be there? Depends on what it is, Robert said.

documents in a sealed container buried above the waterline.

Maybe, but we’re talking about finding something the size of a briefcase in 30 square miles of swamp.

She gave us exact coordinates, Sarah said, looking back at the girl’s face on the screen.

She risked everything to leave that message.

We have to try.

3 weeks later, Sarah stood at the edge of Lake Poner Train, watching Dawn break over the water.

The expedition had required permits from the National Park Service, cooperation from local law enforcement, and the expertise of Dr.

Raymond Arseno, a forensic archaeologist from Two-Lane University who specialized in wetland excavation.

The team assembled on a small dock, Sarah Marcus, Robert James Raymond, and two graduate students who would assist with any recovery operation.

They loaded equipment onto two flat bottom boats, ground penetrating radar, metal detectors, excavation tools, and documentation cameras.

The coordinates put us about 40 minutes north, Raymond explained, studying a GPS unit.

The good news is the land elevation there is slightly higher, probably a natural levy even in 1858.

The bad news is 166 years of sediment accumulation and vegetation growth.

The boats pushed into the maze of waterways passing beneath canopies of Spanish moss and cypress.

The modern world fell away quickly, replaced by something ancient and watchful.

Sarah imagined the girl, still unnamed in any record they’d found, making the same journey in reverse, perhaps hidden in a small boat, carrying a terrible secret.

There, Raymond called, checking his GPS.

They had reached a small island barely 30 ft across, thick with pomemetto and wild grapevine.

This is it.

Ground penetrating radar first, then we dig only if we get a clear signal.

The team unloaded equipment while Raymond and his students began systematic scans of the island.

Sarah watched the radar screen, seeing layers of soil, root systems, and the ghostly shadows of buried cypress stumps.

Then, in the northeast quadrant, something different.

A geometric anomaly roughly rectangular buried about 4 ft down.

Got something? Raymond said quietly.

man-made metal and possibly wood, substantially decayed.

They began to dig carefully, documenting every layer.

The Louisiana heat was oppressive, humidity thick enough to swim through.

2 hours in, one of Raymond’s students called out.

Her trowel had struck something solid.

Raymon knelt beside her, brushing away soil with his fingers.

Metal appeared, heavily corroded, but intact, the edge of a box.

Sarah’s heart hammered as they carefully excavated around it.

The container was roughly 2 ft long, made of iron, with remnants of a wax seal around its seam.

It had been buried deliberately, carefully by someone who wanted it both hidden and preserved.

“Let’s get it to the surface,” Raymond said.

“We open it at the lab.

” The conservation lab at Tulain University was equipped for exactly this kind of delicate work.

The metal box sat on an examination table, still caked with 166 years of swamp soil, while Raymond’s team prepared to open it under controlled conditions.

Sarah stood beside Marcus, both of them in observation positions behind a glass partition.

Robert and James crowded close, watching monitors that showed multiple camera angles of the box.

Raymond worked slowly, using specialized tools to carefully pry at the corroded seam.

The wax seal had long since deteriorated, but it had done its job.

The box’s interior appeared to be relatively dry.

After 20 careful minutes, the lid separated with a grinding sound.

Inside, wrapped in oil cloth that had mostly disintegrated, were papers.

Raymond lifted them with trembling hands, placing them on an examination tray.

Despite the passage of time, despite the moisture and pressure, the documents were remarkably preserved.

The first was a letter written in formal script on official United States government stationary.

James read it aloud through the intercom from the desk of federal marshal Thomas Bowmont, July 25th, 1858 to be delivered to the district attorney in New Orleans upon my return.

I have gathered sufficient evidence to prosecute Nathaniel Duchamp of Bel Rev Plantation for violations of the act prohibiting importation of slaves.

Enclosed are bills of sale for 17 African captives smuggled through Beritaria Bay in June of this year, as well as correspondence between Duchamp and Captain Hri Mercier of the vessel Nightingale documenting payment of $3,000 for said captives.

The team fell silent.

This was it.

The evidence that had disappeared with Bowmont.

There’s more, Raymond said, carefully separating other documents.

bills of sale, as Bumont had described, a ledger showing payments.

And finally, at the bottom of the box, a small leatherbound notebook.

Sarah’s breath caught.

That’s the same notebook in the dgeray type.

The girl is holding it.

Raymond opened it carefully.

The pages were filled with columns of numbers, dates, and initials.

It’s a smuggling record, he said.

This is Duchamp’s own accounting of his illegal operations.

Dates, prices, sources.

If Bowmont had presented this in court, Duchamp would have been ruined, Marcus finished.

imprisoned, possibly hanged.

Robert leaned against the glass.

So Duchamp killed Bumont, took his evidence and buried it where no one would ever find it.

But the girl saw him.

She knew what he’d done, and somehow, impossibly, she left us away to find the truth.

James was studying the Dgeray type again, now displayed beside the opened box.

Look at how Duchamp positioned her in the photograph.

She’s holding his notebook, the evidence of his crimes, literally in her hands.

He thought he was showing his control over her, showing that even if she knew, she was powerless.

But she wasn’t,” Sarah said softly.

She found a way.

With the truth of Duchamp’s crime confirmed, Sarah became obsessed with identifying the girl.

She returned to Bel Rev’s surviving records with new urgency, searching for any enslaved child between ages 10 and 14 present at the plantation in August 1858.

Mrs.

Tibido at the Louisiana State Archives became an essential partner.

Together, they cross referenced plantation inventories, tax records, and even church baptism registers from nearby parishes.

Finally, in a water-damaged ledger from 1857, they found an entry that made Sarah’s hands shake.

Purchased from the estate of widow Mercier, one girl child, age approximately 11 years, skilled in needle work and housework.

Price: $400.

Name given as Deline.

Mercier.

Sarah breathed the same surname as the ship captain in Bowmont’s evidence.

Mrs.

Tibido was already pulling another file.

The Mercier family were prominent in New Orleans.

Henri Mercier was a merchant captain, but his mother, widow Katherine Mercier, ran a dress making business that, oh my, she looked up, eyes wide, that employed enslaved seamstresses known for extraordinarily fine work.

The pieces fell into perfect alignment.

Delphine had been trained in needle work precise enough to create the microscopic embroidery they’d found.

When Widow Mercier died and her property was sold, Delphine had been purchased by Duchamp, whose illegal smuggling operation involved Widow Mercurier’s son.

Delphine would have known the Mercier family’s business, Sarah said, thinking aloud.

She would have seen documents, overheard conversations.

When she arrived at Bel Rev and saw Duchamp with Marshall Bowmont’s evidence, evidence that mentioned Captain Merier, she understood what it meant.

An 11-year-old child understood federal law and smuggling operations.

Mrs.

Tibido said skeptically.

She’d lived her entire life watching and listening, Sarah replied.

Enslaved people were expected to be invisible, which meant they saw everything.

Delphine knew Bumont was a marshal investigating the Mercier.

She knew that notebook in Duchamp’s hands was evidence of crimes, and she knew that Bumont had disappeared.

Marcus, who had driven to Baton Rouge to join the research, added another document to their growing file.

I found Duchamp’s will.

When he died in March 1859, his property was liquidated to pay debts, including his slaves.

There’s a record of an auction on April 15th, 1859.

Sarah scanned the list of names.

There, Deline, age approximately 12, sold to a buyer listed only as J.

Morrison, New Orleans.

The trail went cold after that.

Morrison could be anyone.

Mrs.

Tibido said it’s one of the most common names in Louisiana.

But Sarah felt closer to Delphine than ever.

The girl who had risked everything to expose a murderer, who had hidden coordinates and threads so fine it was nearly invisible, who had been photographed holding the very evidence of the crimes she witnessed.

We need to find what happened to her after the sale.

Sarah said she deserves to have her full story told.

The search for Delphi’s fate took Sarah to the New Orleans Public Libraries Louisiana Division, where city directories and commercial registers from the Antabellum period were preserved on microfilm.

She spent three days scrolling through endless lists of names looking for any Jay Morrison.

In 1859, she found seven, a lawyer, a doctor, two merchants, a hotel owner, a shipping agent, and a school teacher.

Then, in a cross reference that made her pulse jump, she discovered that Jonathan Morrison, the school teacher, had been a documented abolitionist, one of the few in New Orleans who openly criticized slavery in letters to local newspapers.

But abolitionists didn’t buy slaves, Robert said when Sarah called him with the discovery.

It was morally contradictory.

Unless they were buying people to free them, Sarah countered.

It was rare, but not unheard of.

Abolitionists with financial means would sometimes purchase enslaved people at auction specifically to manummit them.

She found Morrison’s address from the 1859 directory, a house on Doofine Street in the French Quarter.

The building still stood, now divided into apartments.

But the current owner allowed Sarah to search the property’s historical records stored in a basement archive.

There, in a wooden file box that hadn’t been opened in decades, Sarah found what she was looking for.

Notorizzed manumission papers dated May 2nd, 1859, freeing one female child of African descent named Delphine, approximately aged 12 years, purchased at auction for the express purpose of granting freedom.

But there was more.

Attached to the manum mission papers was a letter in Morrison’s handwriting.

This child came to me under circumstances most unusual.

At the auction, she approached me directly, an act of extraordinary courage, and spoke words that still haunt me.

I know where the truth is buried.

She would say nothing more in that public place.

But after the purchase was completed, and we had privacy, she told me a story of murder and hidden evidence that had I not been a man of learning and observation, I might have dismissed as fantasy.

But the detail she provided, the precision of her account, convinced me of its veracity.

I have reported her testimony to the federal authorities, though I fear little will come of it now that Duchamp is dead and cannot face justice.

Nevertheless, I have freed this remarkable child and arranged for her education and care with a family traveling north to Philadelphia, where she might have opportunity for a life her intelligence and courage deserves.

Sarah sat back, tears streaming down her face.

Delphine had survived.

She had been freed.

She had spoken her truth.

But the story didn’t end there.

Sarah’s next destination was Philadelphia, where Morrison’s letter indicated Delphine had been sent.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania held records of the city’s free black community in the 1860s, a population that had grown significantly as formerly enslaved people escaped or were freed before the Civil War.

“The archivist, Dr.

Angela Wright, was intrigued by Sarah’s search.

” “The 1860 census for Philadelphia’s black wards might have her,” she said, pulling up digital records.

If she arrived in late 1859, she would have been counted in June 1860.

They searched through hundreds of entries looking for any girl named Delphine between ages 12 and 15.

Finally, they found her, Deline Morrison.

She had taken her liberator’s surname, listed as a ward in the household of Frederick and Martha Wilson, both free black residents who ran a boarding house on South Street.

The Wilsons, Dr.

Wright said excitedly, recognizing the name, they were prominent in Philadelphia’s black community.

Frederick Wilson was a conductor on the Underground Railroad and a member of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.

This was exactly the kind of household that would have taken in a freed child.

The trail continued through city directories and church records.

In 1865, Delphine appeared in the membership roles of Mother Bethl AM Church.

In 1867, she was listed as a student at the Institute for Colored Youth, one of the nation’s first schools for black students to offer a classical education.

Then in 1872, Sarah found something extraordinary, a marriage record.

Delphine Morrison had married Jacob Reynolds, a teacher at the institute on June 15, 1872.

She was listed as age 25.

Occupation: school teacher.

She became a teacher, Sarah said, her voice thick with emotion.

After everything she survived, she dedicated her life to education.

Dr.

Wright was already searching birth records.

If she married in 1872, there might be children, she pulled up a digitized birth certificate.

Here, Samuel Reynolds, born 1873, parents Jacob and Deline Reynolds.

Over the next hour, they traced three more children, all born between 1873 and 1880.

The family had remained in Philadelphia, part of the city’s growing black middle class.

Jacob Reynolds had become principal of the Institute for Colored Youth.

Delphine had taught there for over 30 years.

She lived until 1921.

Dr.

Wright announced finding a death certificate.

Age 74, she’s buried in Eden Cemetery along with her husband and two of their children.

Sarah sat quietly, absorbing the full arc of Delphine’s life.

From enslaved child, witness to murder to educator who shaped generations of students.

The coordinates she had embroidered into her sleeve weren’t just evidence of a crime.

They were an act of resistance, a refusal to let injustice be buried and forgotten.

“Are their descendants?” Sarah asked.

Dr.

Wright smiled.

“Let me make some calls.

” 6 months after Sarah’s discovery, a crowd gathered in New Orleans at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture traveling exhibition.

The dgeray type of Delphi and Nathaniel Duchamp was displayed in a place of honor alongside the documents recovered from Lake Poncher Train and the full story of Delphi’s courage.

But Sarah’s attention was on the group standing before the display.

Three generations of Delphi’s descendants traced through careful genealological work by Dr.

Wright and a team of volunteer researchers.

There were 12 of them, ranging from a great great granddaughter in her 80s to a 5-year-old boy who kept asking questions about Grandma Deline.

The eldest descendant, Mrs.

Dorothy Harrison held a photograph of her grandmother, Delphine’s youngest daughter, taken in 1910.

The resemblance was unmistakable.

The same determined eyes, the same careful intelligence in her expression.

“We knew she’d come from Louisiana,” Mrs.

Harrison said, her voice trembling.

“We knew she’d been born enslaved, but we never knew the full story.

We never knew what she’d done, how brave she’d been.

” Marcus stood to speak, addressing the assembled crowd.

Delphine was 11 years old when she witnessed a murder and understood that the evidence of that crime and of a larger conspiracy, of illegal smuggling, had been buried to protect a wealthy man.

She had no voice in that society, no rights, no power.

But she had intelligence, courage, and extraordinary skill.

She left a message for the future, hidden in plain sight, knowing that someday someone might find it.

He gestured to the dgerayotype.

For 166 years, she stood in this photograph beside her enslaver, holding the evidence of his crimes in her small hands.

And all that time, written in thread so fine it was nearly invisible, she was telling us where to look for the truth.

Sarah watched the descendants gather around the image, touching the glass gently, speaking quietly to each other and to the girl in the photograph who had given them this gift, the knowledge of her strength, her resistance, her refusal to let murder and injustice remain hidden.

The 5-year-old boy tugged on Sarah’s sleeve.

“Is that really my great great great grandma?” “Yes,” Sarah said, kneeling to his level.

“And she was one of the bravest people who ever lived.

” He studied the image seriously, then looked back at Sarah.

Why did she hide the numbers in her dress? Because sometimes, Sarah said, “When you can’t speak the truth out loud, you have to find another way to tell it.

” And she knew that someday people like you would want to know her story.

The boy nodded, satisfied, and returned to his family.

Sarah stood, looking one last time at Delphine’s face, no longer unidentified, no longer forgotten, no longer silenced.

The photograph had held it secret for 166 years, but Delphine’s message had finally been heard, and the truth she risked everything to preserve would never be buried

News

🔥 Tatiana Schlossberg at 35: Cause of Death Revealed—What Her Husband Endured, How Her Children Were Shielded, and Why Her Low-Key Lifestyle Hid a Fortune No One Talked About 💥 Said with sharp, tabloid bite, the lead suggests the truth cuts deeper than headlines, as insiders hint at hospital corridors, late-night decisions, and a family scrambling to protect legacy while mourning a loss that money, status, and history couldn’t stop 👇

The Untold Tragedy of Tatiana Schlossberg: A Life Shattered Tatiana Schlossberg, a name that once resonated with promise and legacy,…

💔 Dad Didn’t Understand Why His Daughter’s Grave Kept Growing—Until a Hidden Truth Shattered Him and Exposed a Silent Ritual That Left Him Collapsing in Tears at the Cemetery Gates 😭 The narrator whispers with cruel suspense, hinting that what began as confusion turned into a devastating revelation, as the father learns strangers had been secretly visiting, leaving objects, soil, and symbols that transformed grief into a haunting testament of love he never knew existed 👇

The Unraveling of a Legacy Tatiana Schlossberg was not just a name; she was a symbol of a storied lineage,…

💔 BREAKING: JFK’s Granddaughter Dies at 35—A Kennedy Tragedy Rewrites History Again as Tatiana Schlossberg’s Sudden Passing Sends Shockwaves Through a Family Long Haunted by Loss, Leaving America Whispering About Fate, Fragility, and the Price of a Legendary Name The narrator purrs with dramatic disbelief, hinting that this isn’t just another sad update but a chilling reminder that even America’s most storied dynasty cannot outrun sorrow, as insiders describe stunned relatives, hushed phone calls, and a grief so heavy it feels almost scripted by destiny itself 👇

The Unraveling of a Legacy Tatiana Schlossberg was not just a name; she was a symbol of a storied lineage,…

💐 At 35, Tatiana Schlossberg, JFK’s Granddaughter, Laid to Rest—Her Husband’s Heartbreaking Tribute Leaves Family, Friends, and the Nation in Tears as Funeral Honors a Life of Promise, Legacy, and Tragedy Cut Far Too Short The narrator leans in with emotional intensity, insisting this isn’t just a ceremony but a moment of raw grief, love, and history colliding, as tearful attendees, solemn prayers, and intimate reflections reveal the depth of heartbreak no one could ignore 👇

The Shattered Legacy of Tatiana Schlossberg In the heart of a cold January morning, Tatiana Schlossberg, the granddaughter of the…

🔥 Shock and Sorrow: JFK’s Grandchild Tatiana Schlossberg Dies at 35, Leaving Family, Friends, and Admirers Grappling With Sudden Tragedy Delivered with tabloid intensity, the lead teases that grief mixes with disbelief, as her vibrant life, intellect, and promise vanished suddenly, leaving hearts broken and minds searching for answers 👇

The Fallen Star: A Kennedy’s Legacy Shattered In the heart of a winter morning, the world learned of a tragedy…

End of content

No more pages to load