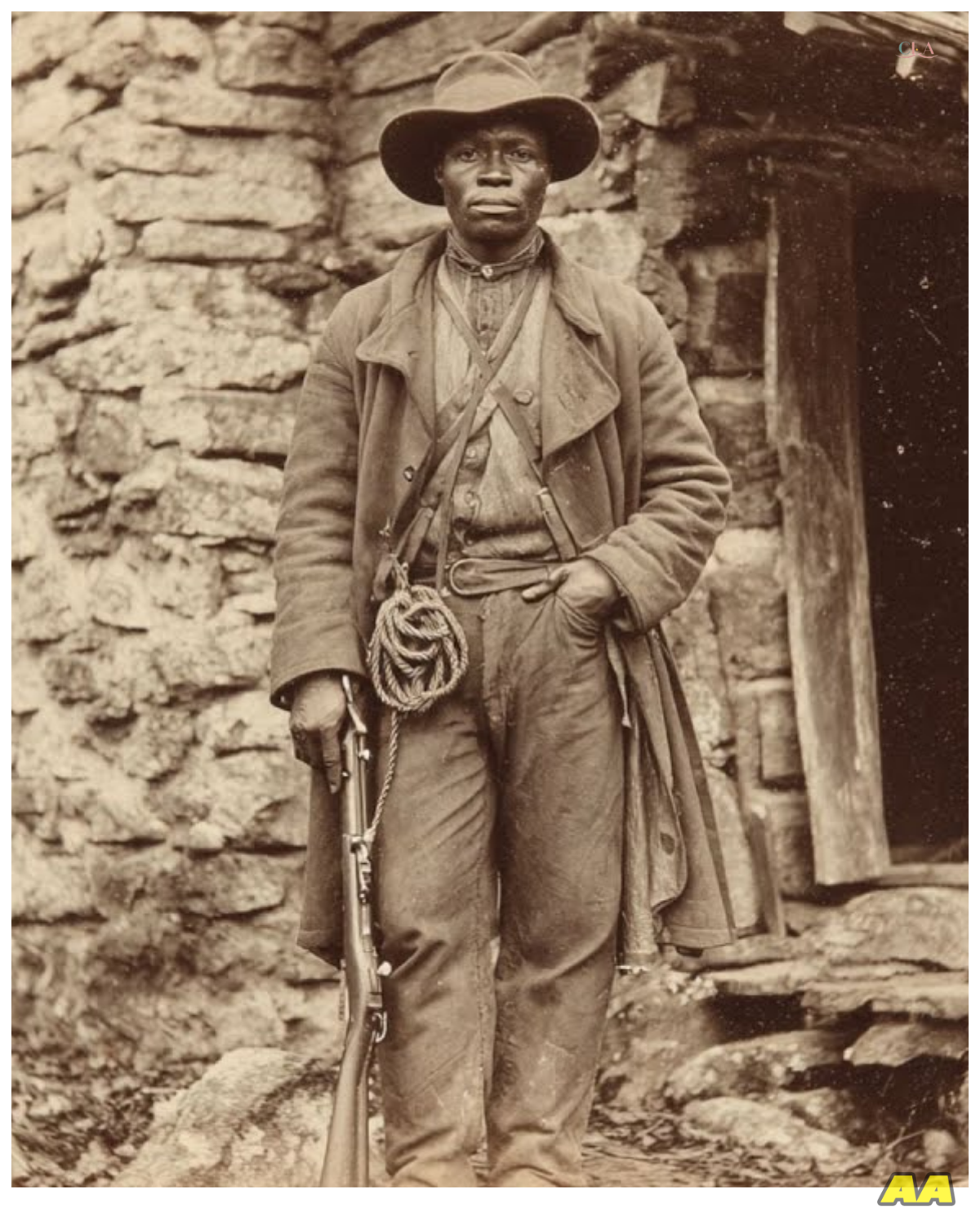

(Blue Ridge, 1856) The Mountain Man Slave Who Turned His Shack Into a Fortress of Revenge

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of Blue Ridge, Virginia.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you are watching from and the exact time you are listening to this narration.

We are interested in knowing to what places and at what times of day or night these documented accounts reach.

In the autumn of 1856, the rolling hills of Blue Ridge County, Virginia, bore witness to events that would challenge every assumption about human nature and the bonds between master and slave.

The story begins not with violence, but with silence.

A silence so complete that even the mountain winds seem to hold their breath around a modest wooden shack perched on the eastern slope of Camels Mountain.

The shack belonged to Isaiah Carter, a Freriedman whose manumission papers dated back to 1852.

At 43 years of age, Carter had built what locals described as an unremarkable dwelling, rough huneed logs chinked with mud and moss, a stone chimney that leaked smoke on windy days, and a single room that measured no more than 12 ft square.

What made the structure notable was not its construction, but its location, isolated by design, accessible only by a narrow deer path that wound through dense stands of chestnut and oak.

If you’re enjoying the story and feel like helping the channel with any amount, please support us by clicking the thanks button and donating whatever you wish.

This really helps the channel keep posting new stories.

Carter had chosen this spot deliberately.

According to land records filed in the Madison County Courthouse, he had purchased the 2acre plot from the estate of Jeremiah Hawkins for the sum of $18, a transaction that raised eyebrows among the white landowners of the valley below.

How, they wondered, had a former slave acquired such funds? The question would prove more significant than anyone imagined.

Benjamin Moore’s plantation lay 7 mi northeast of Carter’s mountain retreat, a sprawling tobacco operation that encompassed nearly 800 acres of fertile bottomland along the Conway River.

Moore, aged 51, had inherited the property from his father in 1848 and had expanded it considerably through the acquisition of neighboring farms.

By 1856, he owned 37 slaves, making him one of the more substantial planters in the county.

The relationship between Moore and Carter traced back to Carter’s childhood.

Born into slavery on the Moore plantation in 1813, Isaiah had served the family for nearly four decades before his unexpected manumission.

The circumstances of his freedom remained unclear to most observers, though plantation records suggest it was connected to the death of Benjamin’s younger brother, Thomas, in 1851.

Thomas Moore had been found dead in his quarters on a November morning, his body showing signs of what the local physician described as apoplelectic seizure.

The timing coincided with Isaiah’s request for freedom papers, a request that Benjamin granted with unusual haste, according to witnesses who recalled the transaction.

The first indication that something had shifted in the relationship between the two men came in late September of 1856.

William Hutchkins, who operated a general store in the village of Kinderhook, later testified that Benjamin Moore had visited his establishment three times in a single week, purchasing items that seemed unrelated to plantation work, rope, nails, a handax, and several pounds of salt pork.

When Hutchkins inquired about the purchases, Moore’s response was described as evasive and agitated.

The storekeeper noted that Moore kept glancing toward the mountains as he spoke, as though expecting to see something or someone among the trees.

During this same period, travelers on the old Indian trail that passed near Carter’s property, began reporting unusual activity around the mountain shack.

Samuel Briggs, a circuit preacher who made monthly visits to remote homesteads, described seeing Carter working on what appeared to be modifications to his dwelling.

The Freedman had been digging what looked like a root cellar, though the excavation seemed unusually deep and wide for food storage.

More troubling were the sounds that drifted down from the mountain on still evenings.

Martha Hensley, whose farm occupied the lower slopes of Camels Back Mountain, told her husband that she had heard hammering that continued well into the night, rhythmic, persistent pounding that seemed to echo off the rocky outcroppings above Carter’s shack.

The transformation of Carter’s modest dwelling began in earnest during the first weeks of October.

According to later investigations, he had somehow acquired materials that far exceeded what his limited resources should have allowed.

Heavy planks of oak, iron hinges, sheets of tin for roofing, and quantities of limestone that would have required multiple wagon trips to transport up the treacherous mountain path.

Local residents puzzled over how Carter was financing these improvements.

His only known source of income came from occasional work as a hunting guide for travelers passing through the region, a profession that typically yielded barely enough to purchase basic necessities.

Yet the materials accumulating around his property suggested access to considerable funds.

The answer lay in a secret that connected Carter’s past servitude to his current circumstances.

During his years on the Moore plantation, Isaiah had served not only as a fieldand, but as a trusted overseer for the family’s more sensitive business dealings.

Benjamin Moore’s prosperity, derived not only from tobacco cultivation, but from his role as a middleman in the regional slave trade, a fact carefully concealed from his neighbors and family.

Carter had been present during numerous transactions, had witnessed the movement of money and documentation, and had gradually pieced together the full scope of Moore’s clandestine activities.

More importantly, he had discovered where Moore kept the records of these dealings, a hidden compartment beneath the floorboards of the plantation smokehouse, containing ledgers that detailed decades of illegal slave trading operations.

The discovery had occurred in the spring of 1851 when Carter was tasked with cleaning the smokehouse after a winter of heavy use.

A loose board had revealed the hiding place, and the contents of the ledgers had provided Carter with a comprehensive understanding of his master’s criminal enterprise.

The knowledge had remained dormant until Thomas Moore’s death created an opportunity for leverage.

Thomas had been more than Benjamin’s brother.

He had been a silent partner in the slave trading operation and the keeper of certain particularly damaging secrets.

His sudden death had left Benjamin vulnerable, and Carter had chosen this moment to present his evidence and demand his freedom.

The manu mission papers had been signed within days of their conversation, but freedom had not satisfied Carter’s sense of justice.

The months following his release had been consumed with planning something far more comprehensive than mere escape from bondage.

The shack on Camel’s Back Mountain was not intended as a simple homestead.

It was being transformed into something unprecedented in the annals of Blue Ridge County, a fortified position from which a former slave would extract a terrible reckoning from his former master.

The modifications Carter made to his dwelling during October of 1856 reflected a methodical understanding of defensive architecture.

The original log walls were reinforced with additional layers of oak planking, creating barriers nearly 8 in thick.

Windows were reduced in size and fitted with heavy wooden shutters that could be barred from the inside.

The roof was strengthened with additional support beams and covered with overlapping sheets of tin that would deflect both weather and projectiles.

Most significantly, Carter had excavated beneath his shack to create what amounted to an underground bunker.

The excavation extended nearly 10 ft below the original floor level and was lined with carefully fitted stones hauled up from the creek bed below.

Multiple chambers connected by narrow passages created a maze-like structure that would allow movement throughout the underground space without exposure to attackers above.

The entrance to this subterranean complex was concealed beneath a heavy wooden trap door that appeared to be nothing more than a root cellar access.

The deception was so complete that even close inspection would fail to reveal the true extent of the excavation beneath Carter’s modest dwelling.

As October progressed into November, Carter’s activities took on an increasingly ominous character.

Neighbors reported seeing him practicing with weapons, an old musket whose origin remained unknown and more disturbing, a crossbow that he appeared to have constructed himself.

The sight of a black man armed with such devices was deeply unsettling to white residents of the valley, though none felt confident enough to challenge his right to possess them.

More troubling still were the observations of those who encountered Carter during his increasingly frequent trips to the valley below.

Rebecca Ames, wife of a small farmer whose land bordered the road leading to Moore’s plantation, described Carter’s appearance as profoundly changed during this period.

The man who had once carried himself with the measured difference expected of a former slave now moved with what she characterized as a predator’s confidence.

The tension building around Carter’s mountain retreat reached a breaking point in mid- November when Benjamin Moore made an unannounced visit to the shack.

According to Carter’s own later testimony, Moore had come to warn him about growing suspicion among local whites regarding his activities.

The plantation owner suggested that Carter might be wise to relocate to another county, perhaps even another state, before his presence provoked more serious attention from authorities.

Carter’s response to this suggestion would later be described by Moore as chilling in its calm determination.

The Freedman had simply smiled and invited his former master to inspect the improvements he had made to his property.

Moore had declined the invitation, but not before noting details that would haunt his memory in the weeks that followed.

The reinforced walls, the modified roof, and most unnervingly, the sound of his own voice echoing in ways that suggested hidden spaces beneath the cabin floor.

The conversation between the two men lasted less than 30 minutes, but its impact would reverberate through the coming months.

Moore returned to his plantation, deeply shaken, and within days had begun making preparations that suggested he understood the gravity of his situation.

He increased the number of armed overseers patrolling his property, restricted his own movements to daylight hours, and most tellingly began liquidating assets in preparation for what appeared to be a hasty departure from the region.

Yet Carter’s plans had progressed beyond the point where Moore’s flight could provide escape.

The Freedman had spent months studying his former master’s habits, learning the routines of the plantation, and identifying the moments of greatest vulnerability.

The fortress he had created on Camel’s Back Mountain was not intended merely as a refuge.

It was the foundation for a campaign of psychological warfare that would unfold over the winter months of 1856 and 1857.

The first phase of Carter’s campaign began on December 3rd when Moore discovered that someone had entered his study during the night and left behind a single item, a page torn from one of the hidden ledgers documenting slave trading transactions.

The page had been placed deliberately on Moore’s desk, weighted down with a smooth riverstone of the type commonly found on Camel’s Back Mountain.

The message was unmistakable.

Carter possessed the evidence of Moore’s criminal activities, and he was prepared to use it, but the manner of delivery was equally significant.

Someone had penetrated the plantation security, entered the main house without detection, and departed without disturbing anything else in the room.

The psychological impact on Moore was immediate and devastating.

Over the following weeks, similar intrusions occurred with increasing frequency.

Items would be moved in Moore’s private quarters, always subtly, always in ways that confirmed unauthorized access without causing actual damage.

A book relocated to a different shelf.

A pen moved from one side of a desk to the other, window latches left unfassened despite being secured the previous evening.

The plantation’s slaves began reporting their own encounters with mysterious disturbances.

Tools would disappear from locked sheds only to reappear days later in unexpected locations.

Livestock would be found in different fields despite secure fencing.

Most unnervingly, several slaves reported seeing a figure moving through the plantation grounds during the darkest hours before dawn.

A figure they recognized but dared not name.

Moore’s response to these psychological assaults revealed the depth of his fear.

He hired additional guards, changed the locks on all buildings, and instituted new security procedures that transformed his prosperous plantation into an armed camp.

Yet the intrusions continued, always managed with a precision that suggested intimate knowledge of the property’s layout and routines.

The situation escalated dramatically on December 21st, the winter solstice, when Moore awoke to find his bedroom window standing open, despite the bitter cold outside.

On the window sill lay another page from the hidden ledgers.

This one documenting a transaction from 1849 that involved the illegal sale of three children to buyers in South Carolina.

Accompanying the document was a note written in Carter’s careful script.

Justice delayed is not justice denied.

This incident marked a turning point in the psychological campaign.

Moore understood that Carter was no longer content with subtle intimidation.

The Freedman was preparing to escalate their conflict to its ultimate conclusion.

The plantation owner’s response was to send word to authorities in Charlottesville, requesting assistance in dealing with what he termed a dangerous insurgent operating in the Blue Ridge region.

The request for official intervention created complications that neither Moore nor Carter had fully anticipated.

The county sheriff, James Thornton, was obliged to investigate reports of criminal activity, but he was also aware of the political sensitivities surrounding conflicts between white land owners and freed men.

The presence of manum mission papers gave Carter legal status that complicated any direct action.

While Moore’s wealth and social position demanded that his concerns be taken seriously, Thornton’s investigation began with an official visit to Carter’s mountain retreat on January 8th, 1857.

The sheriff was accompanied by two deputies and had come prepared for potential resistance, bringing weapons and restraints suitable for arresting a dangerous fugitive.

What they found instead challenged every assumption about the situation they were investigating.

Carter received his visitors with complete composure, offering refreshments and speaking with the educated diction that had always distinguished him among Moore’s slaves.

The shack appeared to be exactly what it claimed to be, a modest dwelling suitable for a freedman of limited means.

The defensive modifications noted by previous observers were subtle enough to seem like ordinary maintenance rather than military preparation.

When questioned about his activities, Carter provided explanations that were both plausible and difficult to verify.

His frequent trips to the valley were attributed to hunting expeditions and occasional work as a guide.

The materials used for his cabin improvements had been purchased, he claimed, with savings accumulated during his years of bondage.

An explanation that was legally impossible to disprove.

Most significantly, Carter’s demeanor during the interview suggested no consciousness of wrongdoing.

He expressed puzzlement at reports of his threatening behavior, wondered aloud about the source of such accusations, and volunteered to cooperate with any official investigation of his conduct.

The performance was so convincing that Sheriff Thornton found himself questioning whether Moore’s complaints had any basis in reality.

The underground chambers that represented the true extent of Carter’s preparations remained completely concealed during the official visit.

The trapoor leading to his subterranean fortress was indistinguishable from an ordinary root seller entrance, and the deputy’s inspection revealed only stored vegetables and preserved meat, provisions entirely appropriate for a mountain dwelling freedman preparing for winter isolation.

Thornton’s report to county authorities concluded that while Carter’s activities merited continued observation, no evidence of criminal behavior had been discovered.

The sheriff recommended that Moore consider resolving his dispute with his former slave through civil rather than criminal proceedings.

Advice that revealed fundamental misunderstanding of the forces already set in motion.

Moore’s reaction to the official investigation’s inconclusive results marked the beginning of his psychological collapse.

The realization that legal authorities could not protect him from Carter’s campaign forced the plantation owner to confront the full implications of his situation.

He was facing an adversary who possessed devastating evidence of his criminal activities, who had demonstrated the ability to penetrate his security at will, and who enjoyed the legal protection accorded to free men under Virginia law.

The winter months that followed would test both men’s resolve to its absolute limits.

Carter’s mountain fortress had become the base of operations for a campaign of vengeance that would challenge every assumption about the relationship between former masters and their liberated slaves.

The isolation that had seemed to protect Moore’s plantation would prove to be its greatest vulnerability, while the modest shack on Camel’s Back Mountain would serve as the foundation for a reckoning that neither man would survive unchanged.

As February storms howled through the Blue Ridge Peaks, residents of the valley below began to sense that something fundamental was shifting in their ordered world.

The sounds that drifted down from Carter’s mountain retreat were no longer those of simple construction.

They carried the rhythm of preparation for conflict that would soon test every boundary of law, justice, and human endurance.

The psychological warfare that had defined the early months of Carter’s campaign intensified as winter deepened into its harshest phase.

Moore’s plantation, once a symbol of prosperity and order, had become a fortress under siege from an enemy who struck without warning and vanished without trace.

The psychological toll on Moore himself was becoming evident to all who encountered him during this period.

Martha Hensley, whose farm occupied the lower slopes below Carter’s retreat, later described hearing sounds from the mountain that defied explanation.

The rhythmic pounding that had characterized Carter’s construction activities had evolved into something more complex.

the clatter of metal on metal, sounds that might have been digging, and most unnervingly, what seemed to be human voices engaged in conversation during the darkest hours of night.

The mystery deepened when travelers began reporting that Carter was no longer alone on his mountain.

James Wellington, a merchant who regularly traveled the Indian Trail that passed near the retreat, testified that he had observed multiple figures moving around the shack during daylight hours.

The individuals appeared to be men, though their identities remained unclear due to the distance and the concealing nature of the mountain terrain.

Investigation into the identity of Carter’s companions revealed a network that challenged official understanding of Freiedman’s activities in the Blue Ridge region.

Through careful questioning of plantation slaves and free blacks in neighboring counties, authorities gradually pieced together evidence of an informal communication system that connected liberated slaves throughout central Virginia.

The network had developed organically over the years following increased manum missions in the 1840s.

Freed men facing economic hardship, legal challenges, or threats from hostile white communities had learned to rely on mutual support that transcended county boundaries.

Carter’s mountain retreat had apparently become a gathering point for men whose own experiences with slavery and freedom had prepared them for the type of confrontation that was developing with Moore.

Among those identified as Carter’s associates were Samuel Brooks, a freedman from Albamal County who had purchased his own freedom through 20 years of labor as a blacksmith.

David Turner, manumitted following his master’s death in 1854, and most significantly Marcus Webb, whose freedom papers dated to 1851, and whose former master had been involved in slave trading partnerships with Benjamin Moore.

The presence of these men at Carter’s retreat transformed what had appeared to be a personal vendetta into something approaching organized resistance.

Each brought skills that complemented Carter’s own abilities.

Brooks contributed metalwork expertise that explained the sounds of hammering heard from the mountain.

Turner provided knowledge of legal procedures gained through his own struggle for recognition as a free man.

Webb possessed intimate knowledge of Moore’s business practices and criminal activities.

Together, these men had spent the winter months not merely fortifying Carter’s mountain position, but developing a comprehensive strategy for exposing the slave trading network that had operated throughout the Blue Ridge region for more than two decades.

Their goal extended beyond simple revenge against Moore to encompass a systematic documentation of criminal activities that could be presented to federal authorities with jurisdiction over interstate slave trading.

The transformation of Carter’s modest shack into a sophisticated intelligence operation became evident when authorities later discovered the full extent of the underground complex.

The excavation that had appeared to be a simple root cellar actually encompassed a series of chambers that served specific functions.

Document storage, weapons cache, meeting room, and sleeping quarters capable of housing a dozen men.

Most remarkably, the freed men had constructed a complete printing operation in the deepest chamber of their underground fortress.

Using equipment acquired through careful purchases in Richmond and Charlottesville, they had assembled the materials necessary to produce written documentation of their discoveries.

The printing press itself was a small hand operated device suitable for producing hand billills and pamphlets.

While stocks of paper and ink suggested preparation for extensive publication activities, the documents discovered in this hidden printing operation revealed the true scope of the freed men’s investigation into slave trading activities.

Over the course of the winter, they had systematically copied and verified information from Moore’s hidden ledgers, cross-referenced transactions with records from other plantations, and identified a network of criminal activity that extended from the Virginia mountains to markets in New Orleans and Charleston.

Their research had uncovered evidence that Moore’s slave trading operations had violated both state and federal laws on numerous occasions.

Transactions involving the illegal separation of families, the forging of ownership documents, and the transportation of slaves across state lines without proper permits created a pattern of criminal behavior that could result in substantial federal prosecution.

More damaging still were documents that implicated other prominent citizens in the illegal slave trade.

The network that Moore had operated included judges, merchants, and political figures whose involvement could create a scandal of regional significance.

The freed men had methodically documented each connection, creating a comprehensive case that could destroy dozens of careers and disrupt the economic foundation of the Blue Ridge slaveolding community.

As March arrived and the mountain snows began to recede, Carter and his associates prepared for the final phase of their campaign.

The evidence they had gathered would be presented simultaneously to multiple authorities.

federal prosecutors with jurisdiction over interstate commerce, newspaper editors in Richmond and Washington, and religious organizations opposed to slavery.

The coordinated release of information was designed to prevent the suppression of evidence that might occur if only one agency received the documentation.

Moore’s awareness of the investigation’s progress came through intelligence gathered by plantation slaves who maintained contact with the Freedman network.

The realization that his criminal activities were being systematically documented by men with legal standing to present evidence to authorities marked the beginning of his complete psychological collapse.

The plantation owner’s behavior during March of 1857 was described by witnesses as increasingly erratic and desperate.

He began destroying records that might connect him to illegal slave trading, though his efforts came too late to eliminate evidence that had already been copied and secured.

His treatment of slaves became harsh to the point of brutality, as though punishing them could somehow undo the investigation that threatened his destruction.

Most tellingly, Moore began making preparations to flee the region entirely.

He initiated the sale of plantation assets, converted investments to portable wealth, and made inquiries about passage to territories where federal authorities might have less reach.

Yet even these preparations were complicated by the network surveillance.

Every attempt to liquidate assets was observed and documented as additional evidence of his consciousness of guilt.

The climax of the entire campaign approached as April brought the end of winter isolation and the return of regular travel to the Blue Ridge region.

Carter and his associates had spent months preparing for a revelation that would expose decades of criminal activity and challenged the fundamental assumptions about the relationship between masters and slaves.

Their mountain fortress had served not merely as a refuge, but as the headquarters for an investigation that would shake the foundations of Virginia’s plantation society.

The carefully orchestrated exposure of Moore’s criminal empire began on April 15th, 1857 when identical packages arrived simultaneously at multiple destinations throughout Virginia and the federal capital.

Each package contained comprehensive documentation of the slave trading network, sworn affidavit from freed men who had witnessed illegal transactions, and detailed maps showing the routes used for transporting slaves in violation of interstate commerce laws.

The recipients of these packages included federal prosecutors, newspaper editors, anti-slavery organizations, and religious leaders whose opposition to the institution of slavery was well established.

The simultaneous delivery ensured that no single authority could suppress the evidence or prevent its publication.

While the detailed documentation made verification of the charges relatively straightforward, the impact was immediate and devastating.

Within days, federal warrants were issued for Moore’s arrest on charges of illegal slave trading, conspiracy to violate federal commerce laws, and tax evasion related to unreported income from criminal activities.

The evidence presented by Carter and his associates was so comprehensive that Moore’s guilt appeared undeniable.

While the network’s careful documentation eliminated any possibility of claiming ignorance or lack of criminal intent, Moore’s response to the collapse of his world was swift and desperate.

Rather than face arrest and the certain destruction of his reputation, he chose to flee the region entirely.

On the night of April 22nd, he abandoned his plantation with only the portable wealth he had managed to accumulate during his frantic liquidation of assets.

Slaves, land, buildings, and livestock were left behind as he disappeared into the Virginia wilderness.

The plantation’s slaves awoke on April 23rd to discover their master’s absence and the effective dissolution of the institution that had defined their existence.

Without Moore’s presence to maintain the plantation’s operations, and with federal authorities seizing assets as evidence in criminal proceedings, the entire community faced an uncertain future that none had anticipated.

Carter’s reaction to Moore’s flight represented a moment of profound complexity in his campaign for justice.

The exposure of criminal activities had succeeded beyond his most optimistic expectations, while the destruction of Moore’s financial empire provided a form of compensation for decades of unpaid labor.

Yet, the plantation owner’s escape from direct punishment, left unresolved the personal dimension of their conflict.

The Freedman’s associates urged him to consider their mission complete.

The slave trading network had been exposed.

Criminal proceedings were underway.

And the broader community of freedman had gained valuable documentation of their right to legal protection under federal law.

From any objective perspective, their campaign had achieved unprecedented success in challenging the power structure that had oppressed them.

Yet Carter himself remained unsatisfied with Moore’s escape from direct accountability.

The man who had profited from human misery for decades, had avoided facing the consequences of his actions, had retained sufficient wealth to establish himself elsewhere, and had escaped the personal reckoning that Carter had spent months preparing.

The psychological dimension of their conflict remained unresolved despite the legal victory they had achieved.

The decision that would define the final phase of their confrontation came during a meeting of the freed men in their underground stronghold on April 26th.

Carter proposed abandoning their mountain fortress to pursue more into whatever refuge he had chosen, extending their campaign beyond the Blue Ridge region to ensure that justice was not merely legal but personal.

His associates voiced strong opposition to this proposal, arguing that further pursuit would expose them to dangers that outweighed any potential benefits.

The debate continued through the night, revealing fundamental differences in how the freedman understood their situation.

Brooks, Turner, and Webb viewed their campaign as a collective effort to establish legal precedences that would protect all freed men from similar abuse.

Carter’s focus remained intensely personal, centered on ensuring that Moore faced individual accountability for the specific crimes committed against those he had enslaved.

By dawn, the group had reached a compromise that satisfied neither perspective completely, but provided a path forward that all could accept.

Carter would be free to pursue more individually, while his associates would remain in the mountains to protect the evidence they had gathered and assist federal authorities with ongoing investigations.

The division of their forces reflected the evolution of their campaign from personal vengeance to broader social justice.

Carter’s departure from the mountain fortress on May 2nd marked the end of one phase of the conflict and the beginning of another.

The man who had spent months transforming a simple shack into a center of resistance now abandoned that position to track his former master across the Virginia countryside.

His associates watched from the mountain as he disappeared along the same trail that had brought Moore to their confrontation months earlier.

The tracking of Moore’s movements proved less difficult than Carter had anticipated.

The plantation owner’s hasty departure had left a clear trail of financial transactions, travel arrangements, and witness sightings that could be followed by anyone with sufficient determination.

Moore’s wealth had provided him with options, but it had also made his movements visible to those who knew how to interpret the signs.

The trail led northwest through the Shenandoa Valley, where Moore had liquidated additional assets through hasty sales to acquaintances who asked few questions about his reasons for departure.

From there, the path turned west toward the mountain passes that provided access to the territories beyond federal authority.

Moore’s destination appeared to be the frontier regions where his criminal past would be less likely to attract official attention.

Carter’s pursuit required resources that his mountain campaign had not demanded, traveling alone across unfamiliar territory, tracking a man with significant financial advantages, and operating without the support network that had sustained him during the winter months.

He faced challenges that tested his resolve to its limits.

Yet the skills developed during his years of servitude, the ability to move unnoticed, to gather information through careful observation, to survive on minimal resources, proved invaluable in this new phase of their conflict.

The confrontation that would end their monthslong campaign occurred in late May at a remote trading post near the Tennessee border.

Moore had stopped to purchase supplies for the final leg of his journey to the frontier territories, believing himself safely beyond the reach of both federal authorities and personal enemies.

His complacency proved to be a fatal miscalculation.

Carter approached the trading post during the pre-dawn hours of May 29th using techniques developed during his nocturnal raids on Moore’s plantation.

The building was isolated.

The nearest neighbors were miles away, and Moore’s presence was confirmed through careful observation of the animals and equipment outside the structure.

The conditions were ideal for the personal confrontation that had been the ultimate goal of Carter’s campaign from its beginning.

The final encounter between the former slave and his master took place in the trading post’s main room, where Moore had been sleeping beside his travel supplies.

Carter’s entrance was silent and undetected until he chose to announce his presence, creating the psychological advantage that had characterized their entire conflict.

The plantation owner’s reaction to seeing his former slave standing over him revealed the depth of fear that months of psychological warfare had created.

The conversation between the two men lasted nearly 3 hours and covered the entirety of their relationship, from Carter’s childhood enslavement to the destruction of Moore’s criminal empire.

Carter demanded not only acknowledgment of the wrongs that had been committed, but also a detailed confession that could be added to the documentary evidence already in federal hands.

Moore’s initial resistance gradually dissolved under the weight of evidence and the realization that his situation had become completely hopeless.

The confession that Moore provided during those final hours detailed criminal activities that extended far beyond what even Carter had discovered during his investigation.

The slave trading network had been more extensive, more profitable, and more systemically cruel than the freed men had realized.

Families had been deliberately separated to maximize profits.

Documents had been forged on a massive scale, and bribes had been paid to officials throughout the region to ensure protection from prosecution.

Most significantly for Carter personally, Moore’s confession included details of specific crimes that had affected Carter’s own family members.

The plantation owner revealed that Carter’s sister, sold to buyers in South Carolina during the 1840s, had been deliberately separated from her children to increase the transactions profitability.

The children had been sold individually to different buyers, ensuring that the family could never be reunited, even if freedom were achieved.

The revelation of these additional cruelties provided the emotional climax of their confrontation.

Carter’s campaign had been motivated by a sense of generalized injustice, but Moore’s confession transformed that abstract grievance into personal anguish of devastating intensity.

The systematic destruction of his family had not been an unfortunate consequence of slavery’s economic necessities, but a deliberate act designed to maximize Moore’s financial gain.

The resolution of their conflict reflected both Carter’s sense of justice and his understanding of practical limitations.

Rather than killing Moore outright, an act that would have made Carter a fugitive from federal law, he chose to leave his former master alive, but completely broken.

The psychological devastation that had been inflicted during months of careful warfare was completed by the extraction of a full confession and the destruction of Moore’s last hope for escape.

Moore was left tied in the trading post with his confession prominently displayed along with directions to the location of Carter’s mountain fortress where federal authorities could find additional evidence.

The plantation owner’s remaining wealth was confiscated as partial compensation for decades of unpaid labor.

Though Carter understood that no amount of money could truly balance the scales of justice for what had been endured, Carter’s departure from the trading post marked the end of the most remarkable campaign of resistance ever mounted by a freedman in Virginia’s Blue Ridge region.

The man who had transformed a simple mountain shack into a fortress of investigation and vengeance had achieved a victory that extended far beyond personal satisfaction to encompass legal precedent and social justice for the broader community of former slaves.

Federal authorities discovered more at the trading post on June 2nd along with the comprehensive confession that completed the documentation of the slave trading network’s criminal activities.

The plantation owner was arrested and eventually convicted on multiple federal charges, receiving a prison sentence that ensured he would never again profit from human misery.

His property was liquidated to provide compensation for identified victims of his criminal enterprises.

The freed men who had supported Carter’s campaign continued their work from the mountain fortress until federal investigators had completed their documentation of the evidence.

Their underground complex became a model for similar resistance operations in other regions.

While their success in exposing criminal activities encouraged other freed men to challenge the injustices they faced, Carter himself disappeared into the western territories, carrying with him the satisfaction of having achieved justice through careful planning, patient execution, and absolute determination.

The mountain fortress he had created stood empty for years afterward, its underground chambers serving as a monument to the possibility that even the most oppressed could find ways to challenge their oppressors when armed with courage, intelligence, and unshakable resolve.

The case became part of federal legal precedent for prosecuting slave trading violations and established important protections for freed men seeking to document crimes committed against them.

The evidence gathered in Carter’s mountain fortress contributed to dozens of additional prosecutions throughout the region, ultimately destroying a criminal network that had operated for more than three decades.

Residents of the Blue Ridge region would speak for generations about the winter when a former slave had transformed a modest mountain shack into a center of investigation and resistance that challenged the fundamental assumptions of their society.

The sounds of preparation that had drifted down from Camel’s Back Mountain during those cold months had indeed been the harbinger of change that some had sensed, though none had imagined the scope of what was being planned in the shadows above their valley.

Years later, when travelers passed the abandoned shack on the mountain, they could still discern traces of the modifications that had transformed it from a simple dwelling into something unprecedented in the history of American slavery.

The reinforced walls remained standing, though weather had begun to claim the roof.

The underground chambers, sealed to prevent accidents, rested beneath the mountain soil, as testimony to what determined men could accomplish when driven by an uncompromising demand for justice.

The mountain winds that had once carried the sounds of Carter’s preparations continued to whisper through the trees around the empty fortress.

But the silence that had once protected Moore’s criminal empire had been permanently broken, replaced by the echoing memory of a former slave who had refused to accept that freedom meant anything less than the complete accounting for wrongs that had been committed in the shadows of Virginia’s mountain country.

The legacy of Carter’s mountain fortress extended far beyond the immediate destruction of Moore’s criminal enterprise.

The precedent established by Freriedman successfully challenging and exposing systematic criminal activity inspired similar efforts throughout the South during the tumultuous years that followed.

The techniques developed for documentation, investigation, and legal action became a model that was adapted by communities facing similar injustices.

In the decades that followed, historians and legal scholars would study the Blue Ridge case as an example of how determined individuals could use existing legal structures to achieve justice, even when those structures seemed designed to protect the very criminals they were challenging.

The comprehensive nature of the evidence gathered by Carter and his associates demonstrated that former slaves possessed both the intelligence and the legal understanding necessary to mount sophisticated challenges to the system that had oppressed them.

The mountain shack itself became a destination for those seeking to understand the history of resistance to slavery in Virginia.

Though officially abandoned, the structure was maintained by local freedmen who recognized its significance as a symbol of what could be accomplished through careful planning and absolute determination.

The underground chambers remained sealed, but their existence served as a reminder of the extent to which Carter had been willing to prepare for his confrontation with injustice.

The sound that still echoes through the hollows of Camels Back Mountain carries with it the memory of that winter when the impossible became reality when a former slave transformed a modest dwelling into a fortress of justice that challenged the foundations of an entire criminal empire.

The silence that had once protected Moore’s illegal activities was replaced by the permanent testimony of those who refused to accept that freedom meant anything less than full accountability for crimes committed in the shadows of Virginia’s Blue Ridge country.

The investigation into Carter’s methods revealed innovations in resistance that had never before been documented in official records.

Federal prosecutors studying the case discovered that the Freriedman had developed a sophisticated intelligence network that extended across multiple counties using coded communications and predetermined meeting locations to coordinate their activities without detection by hostile authorities.

The network’s effectiveness stemmed from its adaptation of communication methods originally developed by enslaved communities to share information about escapes, dangerous masters, and opportunities for freedom.

Carter had transformed these informal systems into a structured organization capable of conducting long-term investigations and coordinating complex legal challenges.

Documents recovered from the mountain fortress showed that the freed men had maintained detailed surveillance records on more than 40 individuals suspected of involvement in illegal slave trading.

Their observations included travel patterns, business relationships, financial transactions, and personal habits that could be used to predict behavior and identify vulnerabilities.

The scope of their investigation extended beyond Virginia’s borders to include contacts in Maryland, North Carolina, and Tennessee, who provided information about interstate slave trading routes.

The comprehensive nature of their intelligence gathering demonstrated organizational capabilities that challenged prevailing assumptions about the intellectual capacity of former slaves.

More significantly, the case established legal precedents that would influence federal prosecution of slavery related crimes for decades to come.

The evidence collection methods developed by Carter and his associates became a model for future investigations.

While their success in documenting criminal activities encouraged other communities to challenge similar injustices through legal channels, the transformation of public perception regarding Freriedman’s capabilities proved to be one of the most lasting impacts of the Blue Ridge case.

Northern newspapers that covered the story emphasized the sophisticated planning and execution that had characterized Carter’s campaign, challenging stereotypes about the intellectual abilities of former slaves that had been used to justify their continued oppression.

Religious organizations throughout the North cited the case as evidence that former slaves possessed the moral and intellectual capacity for full citizenship, contributing to growing pressure for expanded civil rights protections.

The Freriedman’s success in exposing criminal activities through legal channels demonstrated their commitment to working within established institutions rather than resorting to violence or extralegal action.

Southern reaction to the case revealed the extent to which the slaveolding community felt threatened by the precedent it established.

Editorial writers in Richmond and Charleston warned that Carter’s success would encourage similar challenges to established authority.

While plantation owners throughout the region began destroying records that might implicate them in illegal activities, the economic impact of the investigation extended far beyond Moore’s personal financial destruction.

The exposure of the slave trading network disrupted established business relationships, created uncertainty about the legal status of numerous transactions, and forced the reorganization of commercial practices that had operated in violation of federal law for decades.

Insurance companies that had provided coverage for slave trading operations faced substantial claims as the scope of illegal activities became clear.

Banks that had financed such transactions discovered that their collateral included slaves whose ownership was legally questionable, creating financial complications that persisted for years after the initial investigation.

The ripple effects of Carter’s campaign reached into political circles as elected officials scrambled to distance themselves from individuals implicated in the slave trading network.

Several Virginia legislators who had maintained business relationships with Moore found their political careers permanently damaged by association with his criminal activities.

Federal authorities used the Blue Ridge case as a foundation for expanding investigations into slave trading operations throughout the South.

The documentation methods developed by Carter’s group provided a template for gathering evidence that could withstand legal challenges, while their success encouraged other informants to come forward with additional information.

The prosecution of Moore and his associates ultimately resulted in more than 30 criminal convictions and the recovery of hundreds of thousands of dollars in illegally obtained profits.

The financial penalties imposed on convicted traders provided compensation for victims and their families while demonstrating the federal government’s commitment to enforcing anti-trafficking laws.

The social implications of the case extended beyond legal precedent to challenge fundamental assumptions about race relations in antibbellum, Virginia.

The image of former slaves successfully investigating and exposing white criminal activity contradicted prevailing narratives about intellectual and moral hierarchy that had been used to justify slavery.

Educational institutions in the north began incorporating the Blue Ridge case into their curricula as an example of effective resistance to oppression.

The strategic thinking demonstrated by Carter and his associates provided compelling evidence that enslaved people had possessed sophisticated understanding of legal and political systems despite being denied formal education.

The case also influenced emerging discussions about compensation for enslaved labor.

The freed men’s systematic documentation of unpaid work and its economic value provided a model for calculating the financial impact of slavery that would inform future debates about reparations and economic justice.

International observers noted the Blue Ridge case as evidence of America’s internal contradictions regarding human rights and legal equality.

European newspapers covering the story emphasized the contrast between American democratic ideals and the systematic oppression that the investigation had revealed.

The mountain fortress itself became a pilgrimage site for those seeking to understand the history of resistance to slavery.

Visitors from across the country traveled to Blue Ridge County to see the location where former slaves had successfully challenged one of the most powerful institutions of their time.

Local residents gradually came to take pride in their region’s role in advancing civil rights.

Though this acceptance developed slowly and was not universal, some community members continued to view Carter’s actions as a dangerous precedent that threatened established social order, while others recognized the moral courage his campaign had demonstrated.

The underground chambers beneath the fortress were eventually open to researchers studying the history of slavery and resistance.

The artifacts recovered from these spaces provided insights into the daily lives of the freed men during their winter of preparation, revealing the human dimension of their extraordinary campaign for justice.

Personal items found in the chambers included letters from family members separated by slavery, religious texts that had provided spiritual sustenance during their struggle, and handmade tools that demonstrated the ingenuity required to construct their sophisticated intelligence operation without access to conventional resources.

The printing equipment discovered in the deepest chamber was eventually donated to a museum in Richmond where it became part of an exhibit on African-Amean resistance to slavery.

The press itself bore evidence of extensive use, suggesting that the Freriedman had produced far more documentation than was ever discovered by authorities.

Research into the network’s communication methods revealed the existence of a coded language that had allowed the freed men to discuss sensitive topics in the presence of potentially hostile observers.

The sophistication of this code demonstrated linguistic creativity that challenged prevailing assumptions about the intellectual capabilities of former slaves.

The broader impact of Carter’s campaign on federal anti-slavery enforcement became apparent in subsequent years as prosecutors applied the Blue Ridge precedents to cases throughout the South.

The documentation standards established by the investigation became the foundation for more effective legal challenges to slave trading operations.

The success of the freed men in working within legal institutions to achieve justice provided a model for future civil rights activism that emphasized legal challenge and documentation over violent resistance.

This approach would influence reform movements for generations to come, demonstrating the power of strategic thinking and careful preparation in confronting institutional injustice.

The personal cost of Carter’s campaign remained largely hidden from public view.

Those who had known him during his years of enslavement noted that his transformation from differential bondsmen to sophisticated resistance leader had required sacrifices that few could fully understand or appreciate.

His associates who remained in the Blue Ridge region after his departure faced ongoing challenges from community members who resented their role in exposing local criminal activities.

The social isolation they experienced demonstrated the personal courage required to challenge established power structures even when legal protections were available.

The psychological impact of their campaign on the broader Freedman community was complex and long-lasting.

The success of Carter’s methods provided hope that legal challenges could be effective.

While the extent of criminal activity they had exposed revealed the systematic nature of oppression that former slaves continued to face, the Blue Ridge case ultimately established principles that would influence American civil rights law for more than a century.

The precedent that former slaves could serve as credible witnesses in federal criminal proceedings challenged legal assumptions that had denied them equal standing in court proceedings.

The documentation methods developed during the investigation became standard practice for civil rights organizations seeking to expose systematic discrimination and criminal activity.

The comprehensive approach that Carter and his associates had pioneered provided a foundation for future investigations into institutional injustice.

Years after the initial confrontation, residents of Blue Ridge County continued to discover evidence of the extensive preparation that had preceded Carter’s campaign.

Hidden caches of documents, abandoned observation posts, and sophisticated communication equipment revealed the full scope of an operation that had been largely invisible to contemporary observers.

The mountain itself retained traces of the extraordinary winter when a former slave had transformed a modest shack into a center of resistance that challenged the foundations of Virginia’s slaveolding society.

Visitors could still identify the defensive modifications that had protected the freedman during their months of investigation, though time and weather had begun to claim the more visible evidence of their presence.

The legacy of Carter’s fortress extended beyond its immediate impact on slave trading prosecutions to influence broader discussions about justice, resistance, and the capacity of oppressed people to challenge their circumstances through intelligence, determination, and strategic thinking.

The sound that had once carried the preparations for confrontation across the Blue Ridge valleys had been replaced by a different kind of echo.

The lasting testimony of those who had refused to accept that freedom meant anything less than full accountability for crimes committed against them and their families.

In the end, the transformation of a simple mountain shack into a fortress of justice represented more than a successful campaign against criminal activity.

It demonstrated the power of human dignity to overcome even the most systematic oppression when armed with courage, intelligence, and an unwavering commitment to truth.

The mountain winds that continue to whisper through the trees around the abandoned site carry with them the memory of that winter when the impossible became reality.

When former slaves proved that determination and careful planning could challenge even the most entrenched systems of injustice and emerge victorious, the fortress on Camel’s Back Mountain stands as a permanent reminder that justice delayed need not become justice denied.

that even the most modest beginnings can shelter extraordinary courage.

And that the sound of truth once released into the world creates echoes that can never be completely silenced by those who would prefer that certain stories remain untold.

board.

News

✈️ U.S. F-15 FIRST STRIKE — ALLEGED CARTEL DRUG LAB ERASED IN SECONDS AS SKY ERUPTS IN A BLINDING FLASH ✈️ What officials described as a precision operation turned the night into daylight, with jets screaming overhead and a suspected production site reduced to smoking rubble in moments, sending a shockwave across the region and a message that the airspace above is no safe haven for hidden empires 👇

The Last Fortress: A Shocking Revelation In the heart of the Mexican jungle, Diego stood at the entrance of the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE SHATTER ALLEGED TRUCKING NETWORK WITH SOMALI TIES — 83 ARRESTED, $85M IN CASH AND WEAPONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, federal agents swept through depots and dispatch offices, hauling out duffel bags of currency and seizing firearms while stunned neighbors watched a logistics operation authorities claim was hiding a sprawling criminal enterprise behind everyday freight routes 👇

The Shadows of the Ghost Fleet In the heart of the Midwest, where the snow fell like a blanket over…

🚨 FBI & ICE STORM GEORGIA “CARTEL HIDEOUT” — GRENADE LAUNCHER DISCOVERED AND $900K IN DRUGS SEIZED IN A DAWN RAID THAT SHOCKED THE BLOCK 🚨 What neighbors thought was just another quiet morning exploded into flashing lights and tactical vests as agents swept the property, hauling out weapons and evidence while officials described a months-long investigation that culminated in a swift, coordinated takedown 👇

The Unraveling of Shadows: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of Jackson County, Georgia, the air was…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI CRUSH ALLEGED CARTEL TRUCKING EMPIRE — HIDDEN ROUTES MAPPED, DRIVERS DETAINED, AND MILLIONS STACKED AS EVIDENCE 🚨 Before sunrise, highways turned into a grid of flashing lights as agents intercepted rigs, cracked open trailers, and traced coded dispatch logs, revealing what officials describe as a logistics web hiding in plain sight behind ordinary freight lanes 👇

The Fall of Shadows: A Cartel’s Empire Exposed In the dimly lit corridors of power, where shadows danced with deceit,…

🚢 U.S. NAVY TRAPS SINALOA CARTEL’S ALLEGED $473 MILLION “DRUG ARMADA” AT SEA — AND THE HIGH-STAKES STANDOFF UNFOLDS UNDER FLOODLIGHTS AND ROTOR WASH 🚢 Radar screens lit up, cutters boxed in fast boats, and boarding teams moved with clockwork precision as authorities described a sweeping maritime interdiction that turned open water into a chessboard, stacking seized cargo on deck while prosecutors hinted the ripples would travel far beyond the horizon 👇

The Abyss of Deceit: A Naval Reckoning In the heart of the Caribbean, where the turquoise waters glimmered under the…

🚨 1 MIN AGO: DEA & FBI DESCEND ON MASSIVE TEXAS LOGISTICS HUB — 52 TONS OF METH SEIZED AS 20 POLITICIANS ALLEGEDLY TIED TO A SHADOW NETWORK ARE THRUST INTO THE SPOTLIGHT 🚨 What began as a quiet federal probe detonated into a sweeping raid of warehouses and boardrooms, with agents hauling out towering stacks of evidence while stunned insiders whisper that the real shockwave isn’t just the drugs — it’s the powerful names now facing intense scrutiny 👇

Shadows of the Underground: The Texas Cartel Unveiled In the heart of Texas, where the sun sets over sprawling landscapes,…

End of content

No more pages to load