At First, This 1909 Family Photo Appears Cheerful — But a Closer Look at Her Eyes Changes Everything

Rain tapped steadily against the windows of Harvard Medical School’s archives and special collections as Dr.Emma Walsh carefully examined a collection of century old family photographs recently donated for a study on historical disease patterns.

Most images were unremarkable.

Stiff portraits typical of the era.

Families arranged formally in their Sunday best.

But one photograph dated 1909 captured her professional attention.

The sepia image showed a seemingly typical upper middle class American family.

A stern-faced father in a dark suit, a mother in an ornate high-colored dress, two robust young boys, and a daughter of perhaps 12.

Her hair in perfect ringlets wearing a white lace dress.

At first glance, the photograph appeared perfectly ordinary, even cheerful by the standards of the era, with the mother’s slight smile breaking the usual Victorian semnity.

But as Emma studied the daughter’s face more closely, her medical training triggered immediate concern.

The girl’s pupils were dramatically dilated, even in what appeared to be bright studio lighting.

A faint discoloration ringed her irises, and her gaze held a glassy, unfocused quality that contrasted sharply with her siblings cleared expressions.

“Dr.

Patel Emma called to her colleague, a toxicology specialist.

Could you look at this? These pupilary changes and discoloration, they’re consistent with chronic atropene exposure.

Dr.

Vivic Patel examined the photograph through a magnifying glass.

Belladonna poisoning, he confirmed grimly.

And look at how she’s positioned slightly apart from her siblings, the subtle palar, the barely perceptible swelling around the eyes.

This child was being systematically poisoned when this photograph was taken.

Emma checked the identification on the photograph’s reverse.

The Harrison family, Boston, Massachusetts, June 1909.

A separate notation in different handwriting added, “Three months before Eliza’s tragic passing.

” What had begun as routine archival research had suddenly become a window into a century old crime? Emma carefully placed the photograph in a protective sleeve, her mind racing with questions.

“Who was poisoning this child? Was her death investigated, or had someone literally gotten away with murder while posing for a family portrait?” I need to find out what happened to Eliza Harrison,” Emma said, already reaching for her laptop.

And why nobody noticed what these eyes are clearly telling us.

The next morning, Emma and Dr.

Patel conducted a more thorough examination of the photograph using the lab’s digital enhancement equipment.

Under magnification, their initial observations were confirmed and new details emerged.

“The dilation is pronounced and symmetrical,” Dr.

Patel noted as they studied the high resolution scan.

And there is that distinctive rim of discoloration around the iris that’s characteristic of anticolinergic toxicity.

Belladona derivatives were my first thought, but it could be any number of similar compounds.

And what’s particularly disturbing, Emma added, is that these aren’t signs of acute poisoning.

These are manifestations of chronic exposure, regular, small doses administered over time.

They compared Eliza’s appearance to medical texts documenting anticolinergic poisoning cases from the early 20th century.

The similarities were striking.

the madriasis, pupil dilation, the slightly vacant gaze, the subtle facial edema, and a barely perceptible tremor suggested by the slight blurring of the girl’s hands compared to those of her family members.

In 1909, these symptoms might easily have been attributed to a nervous condition or hysteria, Dr.

Patel observed, especially in a young girl approaching adolescence.

Further digital enhancement revealed additional concerning signs.

Eliza’s complexion showed a faint rash characteristic of anticolinergic toxicity.

Her posture, initially appearing merely formal, now seemed to indicate a subtle weakness, with her weight shifted as if she needed the chair’s support.

Most tellingly, while her brothers leaned slightly toward their mother, Eliza maintained a perceptible distance from her father beside whom she was seated.

Chronic lowdosese antiolinergic poisoning would produce exactly this clinical picture.

Emma said pupilary dilation, dry skin, mild confusion, weakness, tacic cardia, all symptoms that could be dismissed as delicate health in that era, particularly in females.

The question is who had both opportunity and motive? Dr.

Patel replied in 1909.

Who would have access to such substances? Emma had already begun researching this angle.

Belladona derivatives were remarkably accessible then.

Present in numerous household preparations from sleep aids to digestive remedies.

Atropene was commonly prescribed for asthma, gastrointestinal spasms, and various inflammatory conditions.

Any adult in the household could have obtained these substances without raising suspicion.

As they compiled their observations into a formal report, both physicians felt the weight of their discovery, a medical crime documented inadvertently by a photographers’s lens, preserved for over a century, and only now being recognized for what it truly was.

Evidence of a slow, deliberate poisoning hidden in plain sight within a seemingly respectable Boston family.

Emma spent the weekend delving into historical records, determined to uncover the Harrison family story.

The Boston Public Libraryies newspaper archives provided her first breakthrough.

An obituary dated September 27th, 1909.

Harrison, Eliza Marie, age 12, beloved daughter of Dr.

William Harrison and Mrs.

Katherine Harrison, passed away September 23rd after a long illness.

She leaves behind brothers Thomas, 14, and James at 10.

Funeral services will be held at Trinity Church on September 29th.

The family requests privacy during this difficult time.

A medical professional.

Emma’s suspicions deepened.

Dr.

William Harrison would have had both knowledge of and access to various pharmaceutical compounds.

Further research revealed he had been a prominent physician specializing in neurological disorders at Massachusetts General.

Hospital library records yielded a Harrison family history published for Boston Centennial in 1922, which painted a picture of wealth and social standing.

Harrisons had been in Boston since the 1850s.

Building their fortune in textile manufacturing before William broke tradition by entering medicine rather than from the family business.

Emma discovered Catherine Harrison had come from the wealthy Reynolds family of Rhode Island, bringing a substantial dowy to her marriage.

Financial records showed William Harrison had taken control of his wife’s inheritance upon their marriage in 1894, as was customary under coverture laws of the period.

Most revealing was an article from the Boston Medical Journal in 1908 announcing an endowment for neurological research established by Dr.

William Harrison funded by a significant inheritance from a family benefactor.

The timing piqued Emma’s interest.

It preceded Eliza’s death by just over a year at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Emma found personal correspondence that shed light on family dynamics.

Letters between Katherine Harrison and her sister revealed growing concerns about Eliza’s health throughout 1908 and early 1909.

Eliza’s condition confounds her physicians.

William insists it is merely nervous stability requiring rest in his prescribed tonics, but I cannot help noticing she seems improved when he travels for medical conferences, only to decline upon his return.

The boys remain robust as ever, while my daughter fades before my eyes.

A later letter was more pointed.

I have begun to keep a private record of Eliza’s symptoms, noting their correlation with certain factors I dare not commit to paper.

William dismisses my concerns with increasing irritation, reminding me of his medical authority and my own nervous tendencies.

I have privately consulted Dr.

Bennett, who suggests removing Eliza to my sister’s care for a period of observation away from our household routines.

Emma sat back, processing these fragments.

The historical record was painting a disturbing picture.

A prominent doctor with financial motivations, a chronically ill daughter who improved in his absence, a mother growing suspicious but constrained by the gender limitations of her era.

And at the center, a child with photographic evidence of antiolinergic poisoning who died three months after that family portrait was taken.

Emma’s investigation led her to the Boston Historical Photography Society, which maintained records from the city’s prominent early photographers.

The Harrison family portrait had been taken at Townsen Studios, one of Boston’s most prestigious photography establishments, patronized by the city’s elite families.

The society’s archavist, Harold Kim, helped Emma locate Townsen’s appointment books and session notes from 1909.

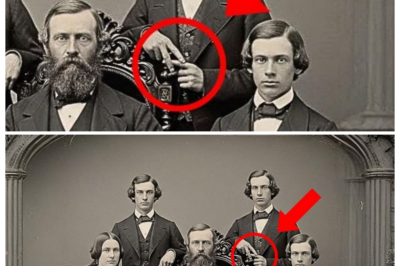

The entry for the Harrison family was brief but revealing.

June 12th, 1909.

Harrison family portrait.

Dr.

William Harrison, Mrs.

Katherine Harrison, sons Thomas and James, daughter Eliza.

Note, Dr.

Harrison requested specific positioning himself beside daughter.

Mrs.

Harrison centered with sons required multiple attempts due to daughter’s difficulty maintaining focus.

Dr.

Harrison administered what he described as her medicine for nervous excitability.

midsession charged standard family rate plus additional for extended session time.

Even more valuable was the discovery of photographer Edward Townsen’s personal journal where he recorded observations about his clients not included in official records.

The Harrison session proved challenging.

The daughter Eliza appeared unwell.

Trembling hands, confusion about simple posing instructions, pupils so dilated her eyes appeared nearly black.

When I suggested postponing due to her apparent illness, Dr.

Harrison became quite insistent we proceed, explaining she suffered constitutional weakness that would not improve with postponement.

Most concerning was the interaction I observed between father and daughter, her visible flinching when he adjusted her position, her gaze consistently averted from him.

When he administered her medicine, drops in water.

Mrs.

Harrison watched with an expression I can only describe as restrained distress.

The boys appeared oblivious, though the elder Thomas was notably protective, twice asking if his sister needed to rest.

I have photographed many unwell subjects.

It is unfortunately common in these times, but something about the situation left me deeply uneasy.

Dr.

Harrison’s insistence on positioning himself beside Eliza, despite my suggestion that the composition would be better balanced otherwise, struck me as oddly deliberate.

Mrs.

Harrison requested a copy of the portrait be sent directly to her sister in Providence, separate from the family order, a request made when Dr.

Harrison was momentarily absent.

Emma felt a chill reading the photographers’s observations.

Townsend had sensed something a miss, but like many in his position, had no authority to intervene in a prominent family’s affairs, especially against a respected physician.

She asked Harold if Towns and had photographed the family on other occasions.

Actually, yes, Harold replied after checking the records.

They had annual portraits taken from 1895 through 1990.

The 1909 sitting was their last.

He pulled earlier Harrison family portraits from the archives.

Examining these images chronologically told a disturbing story.

In Photographs from 1906 and earlier, Eliza appeared healthy, positioned normally within the family group.

The 1907 portrait showed subtle changes, a slight distance from her father, the first hints of the facial characteristics that would become pronounced by 1909.

By the 1908 photograph, the physical signs were unmistakable to trained medical eyes, though perhaps not obvious to lay people of the era.

The progression confirmed Emma’s worst suspicions.

Eliza Harrison had been systematically poisoned over at least two years with increasing dosage or frequency culminating in her death just three months after the final family portrait.

With her growing evidence, Emma secured special permission to access Massachusetts General Hospital’s historical medical archives.

As a Harvard Medical School faculty member researching historical disease patterns, she was granted access to records normally restricted for privacy.

Given their century old status, the hospital archivist located Dr.

William Harrison’s professional files and Eliza’s medical records.

Dr.

Harrison’s credentials were impressive.

Harvard medical school graduate, specialized training in Europe, numerous published papers on neurological conditions.

His hospital standing had been impeccable.

Eliza’s medical file told a different story.

Beginning in early 1907, she had been treated repeatedly for what Dr.

Harrison documented as nervous stability with autonomic manifestations.

His notes described progressive symptoms including visual disturbances, cognitive confusion, cardiac irregularities, and periodic weakness, all consistent with chronic anticolinergic poisoning.

Most tellingly, Dr.

Harrison had consistently rejected consultation requests from colleagues.

A note from Dr.

James Bennett in May 1909 expressed particular concern, have again suggested to Dr.

Harrison that his daughter’s case might benefit from fresh eyes.

While respecting his expertise, the progressive nature of her symptoms warrants broader consultation.

His refusal remains adamant.

Observed patient today in hospital corridor while waiting for her father.

Noted marked madriasis, disorientation, and peripheral flushing inconsistent with diagnosed nervous condition.

When I mentioned these observations to Dr.

Harrison, he reminded me rather sharply of professional boundaries.

Concerns noted privately here should her condition warrant future review.

The hospital pharmacy records showed Dr.

Harrison had regularly ordered various preparations containing atropene, hoccyamin, and scopalamine, all anticolinergic compounds.

ostensibly for his neurological patients.

No direct record connected these orders to Eliza’s treatment, but the timing aligned perfectly with her documented symptomatic episodes.

Most damning was a hidden note Emma discovered folded within Eliza’s file written by the family’s household nurse in August 1909, just weeks before Eliza’s death.

I can no longer remain silent regarding my observations of Miss Eliza’s treatment.

Her symptoms worsened dramatically following administration of the special tonic Dr.

Harrison insists only he must provide.

Mrs.

Harrison has begun to question these treatments, resulting in heated private arguments.

Yesterday, I witnessed Dr.

Harrison administering medicine while Mrs.

Harrison was visiting her sister.

When I inquired about the change in schedule, he dismissed me for the remainder of the day.

I have documented my concerns here should they become relevant to Miss Eliza’s care.

Nurse Mary Callahan, the final entry in Eliza’s file, written by Dr.

Harrison himself stated simply, “Patient succumbed to progressive neurological deterioration on September 23rd, 1909.

No autopsy indicated given clear progression of established condition.

No autopsy.

” “Of course not,” Emma thought.

Dr.

Harrison had ensured there would be no post-mortem examination that might have revealed poisoning.

As both father and physician, his authority would have been nearly absolute, particularly in determining the care of a female child in 1909.

Emma needed to understand why a prominent physician would poison his own daughter.

Working with financial historian Dr.

Robert Chen from the business school, she delved into the Harrison family’s financial records available through public archives.

There’s definitely something irregular here.

Dr.

Chen confirmed after reviewing the documents Emma had gathered.

The Harrison family trust established by Williams father had unusual provisions that appear to be at the center of this situation.

The original trust created in 1889 contained a specific clause.

The bulk of the fortune would pass to Williams children when they reached majority with different conditions for male and female offspring.

Sons would receive their portions at age 21, while daughters would receive substantially larger shares at age 13.

An unusual arrangement explained by the Harrison patriarch’s concern for his granddaughter’s financial security in an era when women had limited earning potential.

Eliza would have turned 13 in November 1909.

Emma noted she died in September, just 2 months before her birthday.

Exactly.

Dr.

Chen confirmed.

And according to these records, her portion of the inheritance, which would have been approximately $2.

8 million in today’s currency, reverted to Dr.

Harrison upon her death.

Had she lived to 13, he would have lost control of those funds entirely.

Further investigation revealed a pattern of financial difficulties hidden beneath the Harrison’s veneer of prosperity.

William Harrison had made several failed investments between 1906 and 1908, significantly depleting his personal capital.

Meanwhile, the textile business managed by his brother-in-law was struggling, putting Catherine’s family money at risk as well.

Most significantly, hospital board minutes from early 1909 referenced Dr.

Harrison’s pledge of substantial personal funds for a new neurological research wing.

A commitment of 50,000, equivalent to over 1.

5 million today that would cement his professional legacy, but required funds he no longer had.

The timing aligns perfectly with the progression we’re seeing in the photographs.

Em observed.

As his financial situation worsened, Eliza’s symptoms increased.

Dr.

Chen pointed out another damning detail.

Just one month after Eliza’s death, William Harrison had made the first payment toward the research wing endowment.

3 months later, he had purchased a substantial property in Beacon Hill and a summer home on the Cape.

By 1910, all evidence of financial distress had disappeared.

He essentially traded his daughter’s life for his financial and professional security, Emma said quietly.

The inheritance trust created the perfect motive, Dr.

Chen agreed.

By ensuring Eliza didn’t reach her 13th birthday, he secured both the family fortune and his professional legacy.

In today’s world, such financial transfers would trigger immediate investigation.

But in 1909, a father had nearly absolute control over family finances and medical decisions.

Emma thanked Dr.

Chen and gathered her notes.

The picture now horrifyingly clear.

A desperate father, a convenient medical expertise, a financial deadline, and a daughter whose life stood between him and financial salvation.

William Harrison had used his medical knowledge not to heal, but to kill, gradually poisoning his daughter while using his professional authority to silence any questions, and it had all been captured in a family portrait.

The evidence hiding in plain sight for over a century in Eliza’s dilated pupils and the subtle distance she kept from the father who was slowly killing her.

Emma’s next focus was Katherine Harrison.

Eliza’s mother, had she been complicit, ignorant, or perhaps another victim of her husband’s deception? The correspondence Emma had already discovered suggested growing suspicions, but she needed to understand what had happened after Eliza’s death.

Through the Massachusetts Historical Society, Emma located a collection of letters donated by the Reynolds family of Rhode Island, Catherine’s relatives.

Among these were extensive correspondences between Catherine and her sister Margaret following Eliza’s death.

The earliest letter dated October 1909 revealed Catherine’s devastated state.

When I suggested postponing due to her apparent illness, Dr.

Harrison became quite insistent we proceed, explaining she suffered constitutional weakness that would not improve with postponement.

Most concerning was the interaction I observed between father and daughter.

Her visible flinching when he adjusted her position, her gaze consistently averted from him.

When he administered her medicine, drops in water.

Mrs.

Harrison watched with an expression I can only describe as restrained distress.

The boys appeared oblivious, though the elder Thomas was notably protective, twice asking if his sister needed to rest.

I have photographed many unwell subjects.

It is unfortunately common in these times, but something about this situation left me deeply uneasy.

Dr.

Harrison’s insistence on positioning himself beside Eliza, despite my suggestion that the composition would be better balanced otherwise struck me as oddly deliberate.

Mrs.

Harrison requested a copy of the portrait be sent directly to her sister in Providence, separate from the family order.

A request made when Dr.

Harrison was momentarily absent.

Emma felt a chill reading the photographers’s observations.

Townsend had sensed something a miss, but like many in his position, had no authority to intervene in a prominent family’s affairs, especially against a respected physician.

She asked Harold if Townsend had photographed the family on other occasions.

Actually, yes, Harold replied after checking the records.

They had annual portraits taken from 1895 through 1909.

The 1909 sitting was their last.

He pulled earlier Harrison family portraits from the archives, examining these images chronologically, told a disturbing story.

In photographs from 1906 and earlier, Eliza appeared healthy, positioned normally within the family group.

The 1907 portrait showed subtle changes, a slight distance from her father, the first hints of the facial characteristics that would become pronounced by 1909.

By the 1908 photograph, the physical signs were unmistakable to trained medical eyes, though perhaps not obvious to lay people of the era.

The progression confirmed Emma’s worst suspicions.

Eliza Harrison had been systematically poisoned over at least 2 years with increasing dosage or frequency, culminating in her death just 3 months after the final family portrait.

With her growing evidence, Emma secured special permission to access Massachusetts General Hospital’s historical medical archives.

As a Harvard Medical School faculty member researching historical disease patterns, she was granted access to records normally restricted for privacy given their century old status.

Hospital archist located Dr.

William Harrison’s professional files and Eliza’s medical records.

Dr.

Harrison’s credentials were impressive.

Harvard medical school graduate, specialized training in Europe, numerous published papers on neurological conditions.

His hospital standing had been impeccable.

Eliza’s medical file told a different story.

Beginning in early 1907, she had been treated repeatedly for what Dr.

Harrison documented as nervous stability with autonomic manifestations.

His notes described progressive symptoms including visual disturbances, cognitive confusion, cardiac irregularities, and periodic weakness, all consistent with chronic anticolinergic poisoning.

Most tellingly, Dr.

Harrison had consistently rejected consultation requests from colleagues.

A note from Dr.

James Bennett in May 1909 expressed particular concern.

Have again suggested to Dr.

Harrison that his daughter’s case might benefit from fresh eyes.

While respecting his expertise, the progressive nature of her symptoms warrants broader consultation.

His refusal remains adamant.

Observed patient today in hospital corridor while waiting for her father.

Noted marked midrias, disorientation, and peripheral flushing inconsistent with diagnosed nervous condition.

When I mentioned these observations to Dr.

Harrison, he reminded me rather sharply of professional boundaries.

Concerns noted privately here should her condition warrant future review.

The hospital pharmacy records show Dr.

Harrison had regularly ordered various preparations containing atropene hyiocyamin and scopoleamine all anticolinergic compounds ostensibly for his neurological patients.

No direct record connected these orders to Eliza’s treatment but the timing aligned perfectly with her documented symptomatic episodes.

Most damning was a hidden note Emma discovered folded within Eliza’s file written by the family’s household nurse in August 1909, just weeks before Eliza’s death.

I can no longer remain silent regarding my observations of Miss Eliza’s treatment.

Her symptoms worsen dramatically following administration of the special tonic.

Dr.

Harrison insists only he must provide.

Mrs.

Harrison has begun to question these treatments, resulting in heated private arguments.

Yesterday, I witnessed Dr.

Harrison administering medicine while Mrs.

Harrison was visiting her sister.

When I inquired about the change in schedule, he dismissed me for the remainder of the day.

I have documented my concerns here should they become relevant to Miss Eliza’s care.

Nurse Mary Callahan.

The final entry in Eliza’s file written by Dr.

Harrison himself stated simply, “Patient succumbed to progressive neurological deterioration on September 23rd, 1909.

No autopsy indicated given clear progression of established condition.

No autopsy.

” Of course not, Emma thought.

Dr.

Harrison had ensured there would be no post-mortem examination that might have revealed poisoning.

As both father and physician, his authority would have been nearly absolute, particularly in determining the care of a female child.

In 1909, Emma needed to understand why a prominent physician would poison his own daughter.

Working with financial historian Dr.

Robert Chen from the business school, she delved into the Harrison family’s financial records available through public archives.

There’s definitely something irregular here.

Dr.

Chen confirmed after reviewing the documents Emma had gathered.

The Harrison Family Trust established by Williams father had unusual provisions that appear to be at the center of this situation.

The original trust created in 1889 contained a specific clause.

The bulk of the fortune would pass to Williams children when they reached majority with different conditions for male and female offspring.

Sons would receive their portions at age 21, while daughters would receive substantially larger shares at age 13.

an unusual arrangement explained by the Harrison Patriarch’s concern for his granddaughter’s financial security in an era when women had limited earning potential.

Eliza would have turned 13 in November 1909.

Emma noted she died in September, just 2 months before her birthday.

Exactly.

Dr.

Chen confirmed.

And according to these records, her portion of the inheritance, which would have been approximately $2.

8 million in today’s currency, reverted to Dr.

Harrison upon her death.

Had she lived to 13, he would have lost control of those funds entirely.

Further investigation revealed a pattern of financial difficulties hidden beneath the Harrison’s veneer of prosperity.

William Harrison had made several failed investments between 1906 and 1908, significantly depleting his personal capital.

Meanwhile, the textile business managed by his brother-in-law was struggling, putting Katherine’s family money at risk as well.

Most significantly, hospital board minutes from early 1909 referenced Dr.

Harrison’s pledge of substantial personal funds for a new neurological research wing, a commitment of 50,000, equivalent to over 1.

5 million today that would cement his professional legacy, but required funds he no longer had.

The timing aligns perfectly with the progression we’re seeing in the photographs Emma observed.

As his financial situation worsened, Eliza’s symptoms increased.

Dr.

Chen pointed out another damning detail.

Just one month after Eliza’s death, William Harrison had made the first payment toward the research wing endowment.

Three months later, he had purchased a substantial property in Beacon Hill and a summer home on the Cape.

By 1910, all evidence of financial distress had disappeared.

He essentially traded his daughter’s life for his financial and professional security, Emma said quietly.

The inheritance trust created the perfect motive, Dr.

Chen agreed.

By ensuring Eliza didn’t reach her 13th birthday, he secured both the family fortune and his professional legacy.

In today’s world, such financial transfers would trigger immediate investigation.

But in 1909, a father had nearly absolute control over family finances and medical decisions.

Emma thanked Dr.

Chen and gathered her notes.

The picture now horrifyingly clear.

A desperate father, a convenient medical expertise, a financial deadline, and a daughter whose life stood between him and financial salvation.

William Harrison had used his medical knowledge not to heal, but to kill, gradually poisoning his daughter while using his professional authority to silence any questions.

And it had all been captured in a family portrait.

The evidence hiding in plain sight for over a century and Eliza’s dilated pupils and the subtle distance she kept from the father who was slowly killing her.

Emma’s next focus was Katherine Harrison, Eliza’s mother.

Had she been complicit, ignorant, or perhaps another victim of her husband’s deception? The correspondence Emma had already discovered suggested growing suspicions, but she needed to understand what had happened after Eliza’s death.

Through the Massachusetts Historical Society, Emma located a collection of letters donated by the Reynolds family of Rhode Island, Catherine’s relatives.

Among these were extensive correspondences between Catherine and her sister Margaret following Eliza’s death.

The earliest letter dated October 1909 revealed Catherine’s devastated state.

The lack of forensic sophistication created another layer of protection.

Without routine toxicology screenings and with a physician signing the death certificate, there simply wasn’t a mechanism to detect this kind of poisoning unless someone specifically suspected and investigated it.

Dr.

Martinez noted.

Social dynamics provided the final layer of protection.

Boston’s elite circles operated on rigid codes of privacy and propriety.

She explained, “Family matters remained strictly private, and questioning a prominent family’s narrative about their daughter’s health would have been considered deeply inappropriate.

Even if staff or associates had suspicions, speaking them aloud could cost them their positions and reputations.

Together, these factors had created perfect conditions for William Harrison’s crime.

medical authority that went unquestioned, easy access to unregulated poisons, symptoms that matched accepted notions of female nervous disorders, limited forensic capabilities, and social codes that enforced silence.

What’s remarkable isn’t that he got away with it, Dr.

Martinez concluded, but that Catherine was able to discover the truth at all.

Her ability to piece together what happened even after the fact speaks to extraordinary perception and courage given the constraints she faced.

that she documented everything, even knowing she couldn’t act on it, suggests she hoped someday the truth would emerge.

And it has, Emma said quietly.

Although a century too late for justice.

Not too late for truth, though, Dr.

Martinez replied.

There’s value in acknowledging historical injustices, even when the victims and perpetrators are long gone.

It honors Eliza’s memory and recognizes Catherine’s impossible position.

More practically, it provides an important case study in how authority can be abused when questioning it is culturally or structurally difficult.

A lesson still relevant in many contexts.

Today, Emma realized her discovery had transcended, a simple historical curiosity to become something more significant, the long delayed revelation of a truth that powerful.

Forces had conspired to keep hidden, and a window into how authority, gender, and professional status could combine to enable and then conceal a terrible crime.

6 months later, Emma stood in the gallery of Harvard Medical School’s newly opened exhibition, hidden in plain sight, medical evidence and historical photographs.

At its center was the 1909 Harrison family portrait, enlarged and dramatically lit to highlight Eliza’s dilated pupils and the subtle signs of chronic poisoning that had gone unrecognized for over a century.

The exhibition had generated significant interest, attracting medical professionals, historians, and the general public.

It presented the full story Emma had uncovered, the medical evidence visible in the photograph, the financial pressures that motivated William Harrison, Catherine’s thwarted attempts to save her daughter and later exposed the truth, and the brother’s lives shaped by their family trauma.

Most powerful was the timeline display showing Eliza’s progression across multiple family photographs from 1906 to 1909, with medical annotations highlighting the increasing signs of poisoning visible in each successive image.

alongside ran financial records showing William Harrison’s declining fortunes and subsequent recovery immediately following his daughter’s death.

“You’ve created something extraordinary here,” said Dr.

Bennett, who had supported Emma’s investigation from the beginning.

“This isn’t just historical revelation.

It’s a powerful teaching tool about observation, ethics, and the dangers of unquestioned authority.

” Medical students clustered around the detailed explanations of antiolinergic poisoning symptoms, many expressing shock that such clear signs had been photographically documented yet missed by everyone around Eliza.

It seems so obvious once you know what to look for, one student remarked.

That’s precisely the point, Emma replied.

We see what we’re prepared to see, what cultural contexts allow us to see.

In 1909, no one was prepared to see a prominent physician poisoning his daughter, so the physical evidence was attributed to other causes or simply overlooked.

The exhibition had attracted unexpected attendees, distant relatives of the Harrison and Reynolds families, drawn by media coverage of the historical discovery.

Among them was Elellanena Reynolds, Catherine’s great grand niece, who had brought additional family letters that filled in the final chapter of Catherine’s story.

After separating from William, she dedicated herself to quietly supporting organizations for women’s legal rights and child protection.

Elellanar explained uh she never spoke publicly about what happened to Eliza, but her substantial anonymous donations helped establish some of the first children’s advocacy organizations in New England.

Most poignant was a previously unknown photograph.

Elellaner shared Catherine in her later years wearing a locket that when opened contained a tiny portrait of Eliza and a lock of her hair.

She carried her daughter with her everyday for the rest of her life,” Elellanar said softly.

And while she couldn’t obtain justice, she worked to create a world where other mothers might have the legal standing she lacked.

As the exhibition concluded its opening night, Emma reflected on the strange journey that had begun with a simple archival photograph.

What had started as a medical historian’s observation had evolved into the solving of a century old crime, the vindication of a mother’s suppressed accusations, and a powerful case study in how authority and gender dynamics could conceal even the most visible evidence.

The 1909 family portrait now stood as both evidence and warning.

A reminder that truth can be captured inadvertently, preserved across time, and eventually revealed when seen through eyes, finally prepared to recognize what has been hiding in plain sight all along.

In Eliza’s dilated pupils, visible to everyone but truly seen by no one for over a hundred years, lay a lesson about observation, power, and the courage required to challenge accepted narratives when vulnerable lives hang in the balance.

Emma had given Eliza Harrison the justice that had been denied in her lifetime.

Not legal justice, now impossible, but the justice of truth acknowledged, of her story finally told, and of her suffering recognized not as mysterious illness, but as the crime it had always been.

In doing so, she had honored not just Eliza, but Catherine as well, the mother who had discovered the truth too late to save her daughter, but had preserved the evidence that would eventually reveal it to the world.

News

Why were historians shocked when they enlarged this 1860 family photo? The photograph arrived at the Virginia Museum of History in a cedar box wrapped in silk that had yellowed with age. Dr.Sarah Chen, the museum’s lead curator for Civil War collections, lifted it carefully from its protective casing. The Dgero type was remarkably well preserved, its silver surface still reflecting light after more than a century and a half. Five people stared back at her from 1860. A prosperous white family, clearly wealthy, judging by their clothing and the elaborate studio setting. The patriarch sat in the center, a stern-faced man in his 50s with a thick beard and dark suit. His wife stood beside him, one hand resting on his shoulder, her dressed in elaborate creation of silk and lace. Three young men, presumably their sons, completed the composition. Two standing behind their parents, one seated to the father’s left. Sarah had examined thousands of antabbellum photographs. This one followed all the conventions, formal poses, serious expressions, the careful arrangement of bodies to demonstrate family hierarchy and respectability.

Why were historians shocked when they enlarged this 1860 family photo? The photograph arrived at the Virginia Museum of History…

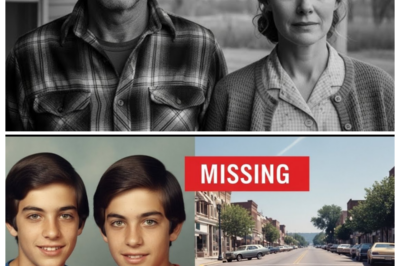

⚖️Colorado’s long-unsolved 1992 and 1998 cases reach a jaw-dropping conclusion as arrests are made, igniting panic, whispered accusations, and reopened wounds across a community that thought the past had settled — Delivered with theatrical intensity, the moment is less about closure and more about reckoning, as decades of quiet deception crumble under one devastating revelation👇

The Shadows of Silence: A Tale of Betrayal and Redemption In the heart of rural Colorado, where the mountains loom…

🕰️Michigan’s 1993 cold case finally unravels decades of silence as a shocking arrest rattles a community that thought the past was safely buried, exposing secrets, lies, and betrayals that many assumed were long forgotten — In a narrator’s tense, biting tone, neighbors whisper in disbelief, old friends exchange suspicious glances, and the quiet streets are suddenly haunted by the truth that justice sometimes waits decades to strike👇

Shadows of the Past In the heart of a snow-covered Michigan town, Hilary Evans was just a girl with dreams,…

🕰️Minnesota’s 1973 cold case erupts back into the spotlight as a decades-old murder is finally solved, leaving a tight-knit community reeling in disbelief, whispers of secrets long buried, and neighbors questioning everything they thought they knew about their friends, family, and the quiet streets they call home — In a narrator’s biting, suspenseful tone, the arrest lands like a thunderclap, turning memories into evidence and showing how the past never truly lets go👇

Echoes of Silence: The Carvalho Twins’ Haunting Legacy In the summer of 1973, Michael and Daniel Carvalho, sixteen-year-old twins, vanished…

End of content

No more pages to load