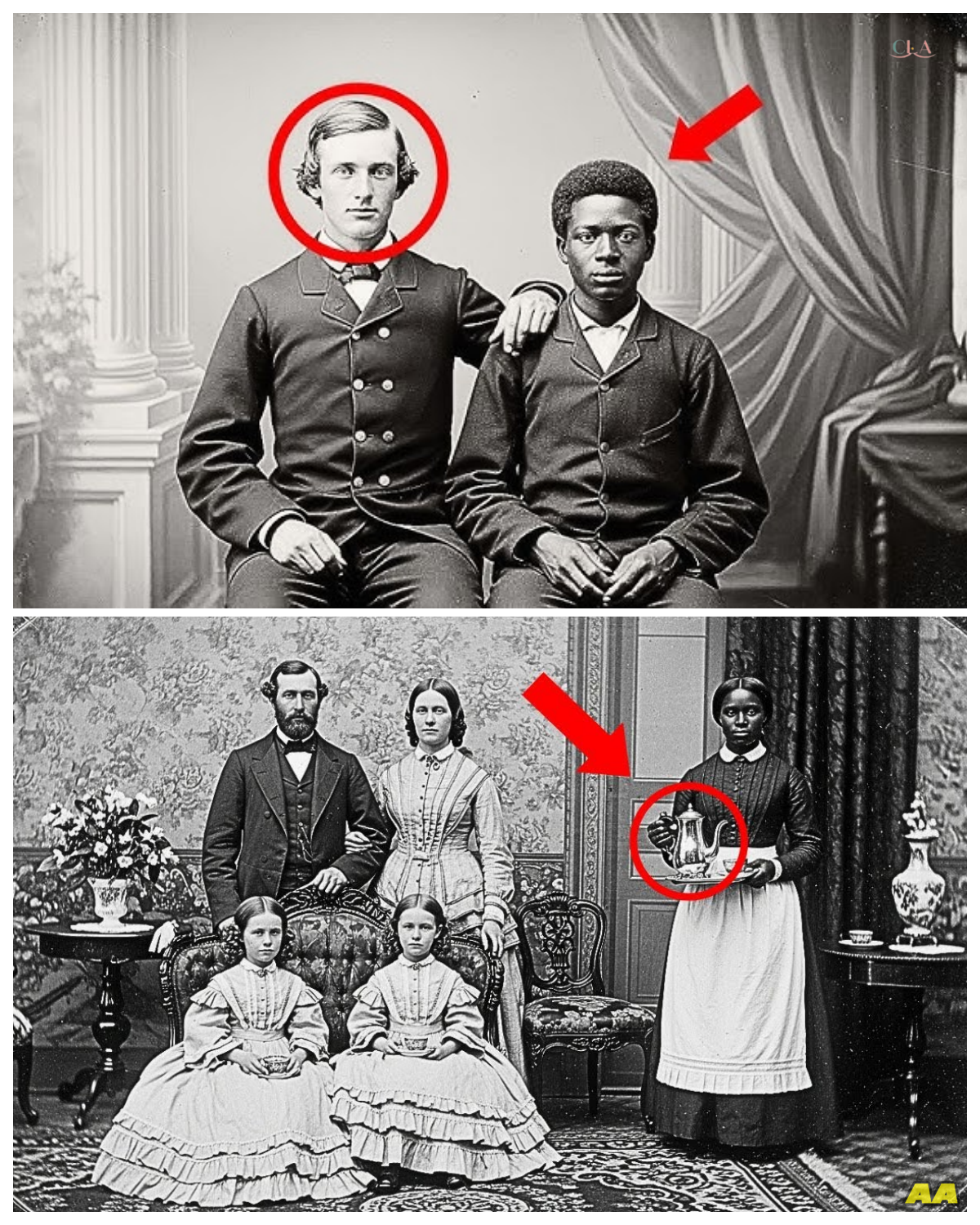

A happy family portrait from 1863 hid a deadly secret in plain sight, which the slave was hiding

A happy family portrait from 1863 hid a deadly secret in plain sight which the slave was hiding.

Sarah Chen, a forensic historian specializing in Civil War era photography, sat in her Boston office examining a dgeray type she’d acquired from an estate sale in Virginia.

The 1863 image showed the perfect picture of domestic tranquility.

The Whitmore family of Richmond posed in their parlor, all smiles and Victorian elegance.

Father Richard stood confidently behind his seated wife, Constance, while their two daughters, ages 12 and nine, sat primly in matching dresses.

But it was the fifth figure that captured Sarah’s attention.

A young black woman standing slightly apart from the family holding a silver tea service.

Unlike typical portraits, where enslaved servants were positioned at the edges or background, this woman stood prominently, almost as if she were part of the family composition itself.

Sarah adjusted her magnifying glass and leaned closer.

The woman’s expression struck her as unusual.

While the Whitmore family beamed with practiced confidence, the servant’s smile seemed different, tight, controlled, almost triumphant.

Her eyes, remarkably clear in the highquality image, held something Sarah couldn’t quite identify.

Not fear, not resignation, but something that looked disturbingly like satisfaction.

Then Sarah noticed the details that would haunt her for months.

The silver teapot the woman held gleamed prominently in the photograph, positioned almost ceremonially.

Mrs.

Whitmore’s hand reached toward a teacup on the side table, frozen mid gesture.

The family’s expressions, which Sarah had initially read as happiness, now seemed slightly strained upon closer examination.

Mr.

Whitmore’s smile didn’t quite reach his eyes, and one daughter’s face showed a faint grimace.

On the back of the Dgeray’s frame, Sarah found an inscription in faded ink.

The Whitmore family, April 14th, 1863.

Final portrait.

The word final sent a chill down her spine.

She immediately began searching historical records for the Whitmore family of Richmond, Virginia.

And what she discovered in a Richmond newspaper archive made her blood run cold.

Tragic deaths of prominent family.

April 15th, 1863.

The Whitmore household found deceased under mysterious circumstances.

Authorities investigating.

This photograph had been taken the day before they all died.

Sarah spent the next week immersed in digitized archives of Richmond newspapers from April 1863.

The story that emerged was sensational enough to dominate local coverage despite the civil war raging around them.

The Richmond Dispatch ran the headline, “Entire family perishes, poisoning suspected.

” According to the April 16th article, “A neighbor had discovered the bodies after noticing that the Whitmore house had been unusually quiet for 2 days.

Richard Whitmore, 45, was found in his study.

Constance Whitmore, 42, was in the parlor.

The two daughters, Emma and Charlotte, were in their bedrooms.

All had died in apparent agony, showing signs of severe poisoning, violent convulsions, discolored skin, and bloody vomit.

The authorities had immediately suspected arsenic, commonly used as rat poison, and readily available in most households.

The initial investigation focused on possible Confederate sympathizers, as Richard Whitmore had been a vocal unionist in increasingly secessionist Richmond, making him unpopular and potentially targeted.

But then Sarah found a follow-up article from April 20th that changed everything.

Slave woman vanished, prime suspect in Whitmore poisonings.

The article named her Grace, age 26, described as a house servant of molatto complexion, literate, known for her skill in the kitchen in serving tea.

She had disappeared the morning after the photograph was taken before the bodies were discovered.

The newspaper painted Grace as cunning and dangerous, claiming she had poisoned the family’s evening tea and fled undercover of darkness.

A reward of $500 was offered for her capture, dead or alive.

Subsequent articles tracked the manhunt.

reported sightings in Petersburg, rumors she’d joined Union lines, speculation she drowned attempting to cross the James River.

But Sarah noticed something the contemporary investigators had apparently missed or chosen to ignore.

None of the articles explored why Grace might have done it.

None questioned what her life had been like in the Whitmore household.

The narrative was simple.

Ungrateful slave murders.

Benevolent family.

Case closed.

Sarah stared at the Dgeray again at Grace’s enigmatic smile and wondered what really happened in that house.

Sarah contacted Dr.

from Marcus Webb, a colleague at Howard University, who specialized in slavery records and genealological research of African-Americans in the antibbellum South.

She sent him the Dgera type and the newspaper articles, asking if he could help trace Grace’s history before the Whitmore.

Marcus called her 3 days later, his voice tight with controlled anger.

Sarah, I found her.

Grace wasn’t born into slavery.

She was born free in Pennsylvania.

Her full name was Grace Morrison.

She was kidnapped in 1855 at age 18 and sold south through a network of slave traders operating along the Mason Dixon line.

Sarah’s stomach turned.

How did you confirm this? Philadelphia newspapers from 1855 reported her disappearance.

Her father, James Morrison, a successful barber, placed advertisements searching for her for years.

He filed legal complaints, contacted abolitionist organizations, even traveled to Richmond himself in 1857, trying to buy her freedom.

The Whitmore refused every offer, claiming she was theirs legally and that Morrison’s claims were fraudulent.

Marcus sent Sarah scanned documents.

Grace’s free papers from Pennsylvania, listing her birth in 1837.

James Morrison’s desperate letters to Quaker abolitionists, legal petitions dismissed by Virginia courts.

The paper trail painted a heartbreaking picture of a father’s feudal struggle against a system designed to protect slaveholders above all else.

There’s more, Marcus continued.

I found probate records from Richard Whitmore’s father, who died in 1859.

Grace was listed in the estate inventory valued at $1,200.

The notation says, “House servant, literate, excellent cook and seamstress.

” That literacy is important, Sarah.

Teaching enslaved people to read was illegal in Virginia.

Either she hid her education or the Whitmore exploited it while technically breaking their own laws.

Sarah studied the Dgero type with new understanding.

Grace’s prominent position in the photograph suddenly made terrible sense.

She wasn’t being honored or included.

She was being displayed as property, as evidence of the Whitmore’s wealth and status.

The tea service she held wasn’t just a prop.

It was a symbol of her forced labor, her skills commodified and controlled.

Marcus, Sarah said slowly, if someone had been kidnapped, enslaved for 8 years, and repeatedly denied freedom despite their father’s attempts to rescue them, what would drive them to murder? The question, Marcus replied quietly, is what took her 8 years to do it.

Sarah traveled to Richmond, walking the streets of the historic district where the Whitmore had lived.

The house no longer stood, destroyed during the Civil War’s final days when Richmond burned in 1865.

But City Records provided the exact location, 412 Grace Street.

A bitter irony that didn’t escape Sarah’s notice.

At the Library of Virginia, she found something extraordinary.

A diary kept by Margaret Hayes, a neighbor of the Whitmore.

The entries from 1860 to 1863 provided a window into the household dynamics that newspapers never captured.

Margaret’s January 1861 entry read, “Called on Constance Whitmore today, found her in foul temper, beating her girl Grace for some trivial offense involving improperly starched linens.

The girl bore the blows without sound, which seemed to infuriate Constance further.

I was embarrassed to witness such a scene, but said nothing.

” These domestic matters are not my concern.

Other entries painted a pattern of abuse.

Grace was struck for minor mistakes, denied food as punishment, and forced to work from before dawn until late at night.

Margaret noted that Grace slept in a small storage room under the stairs with no heat, even during harsh winters.

But the diary also revealed Grace’s intelligence and resilience.

Margaret wrote in March 1862, “Grace served tea today with such precision and grace that I complimented Constance on her servants training.

” Constance replied coldly that Grace required constant discipline to maintain proper behavior, though I noticed the girl anticipating our needs without instruction.

There is something in her eyes, a watchfulness that unsettles me.

The most revealing entry came from April 1863, just days before the photograph.

Richard Whitmore refused yet another offer to purchase Grace’s freedom.

A man claiming to be her father arrived from Pennsylvania with $2,000, a fortune.

But Richard dismissed him cruy, saying Grace was too valuable to lose, and that he doubted the man’s claims.

I saw Grace watching from the doorway.

Her expression was utterly blank, but her hands gripped the door frame until her knuckles went white.

Sarah photographed every page, her hands trembling.

Grace had watched her last hope of freedom destroyed.

Her father had come so close only to be turned away by Richard Whitmore’s greed and cruelty.

Three days later, the family posed for their final portrait, all smiles, while Grace stood behind them holding the tea service, the instrument of their death.

Sarah consulted Dr.

Rebecca Torres, a toxicologist at Massachusetts General Hospital with expertise in historical poisoning cases.

She showed Rebecca the autopsy descriptions from the 1863 newspaper articles and asked what poison might have been used.

Rebecca studied the symptoms carefully.

Based on the descriptions, violent convulsions, bloody vomit, rapid death within hours.

This is almost certainly white arsenic, arsonous oxide.

It was extremely common in the 1860s.

Used for rat poison, fly paper, even complexion treatments.

Easily accessible, easily disguised in food or drink.

How much would be needed to kill a family of four? Sarah asked.

Not much.

A teaspoon dissolved in liquid could kill multiple people.

The trick would be masking the taste.

Arsenic has a slightly sweet metallic flavor.

Strong tea, especially if heavily sweetened or mixed with cream, could potentially hide it.

Rebecca pulled up historical medical texts on her computer.

Here’s the interesting part.

Poisoning with arsenic requires planning.

It doesn’t work instantly.

The poisoner needs to administer it.

Then wait.

If Grace did this, she would have served the poison tea, then stayed in the house as they died.

That takes extraordinary nerve and frankly deep hatred or desperation.

Sarah showed Rebecca the dgeraype.

This was taken the day before they died.

Grace is holding the tea service.

Rebecca leaned closer, examining the image.

Look at Mrs.

Whitmore’s hand.

She’s reaching for the teacup.

If this photograph was taken in the afternoon, as was customary, and the family died that evening or the next morning, it’s possible the tea Grace is holding in this image is already poisoned.

She’s literally photographed with the murder weapon.

Would she have known they’d die this way? Sarah asked.

The suffering, I mean.

Absolutely.

Arsenic poisoning is excruciating.

The victims experience intense abdominal pain, uncontrollable vomiting and diarrhea, burning sensations throughout their body.

They remain conscious throughout most of it, aware of what’s happening.

If Grace poisoned them, she knew exactly what she was condemning them to endure.

Sarah looked again at Grace’s smile in the photograph.

That strange controlled expression.

It wasn’t satisfaction.

She now realized it was certainty.

Grace knew what was coming.

She’d already made her decision, already added the poison.

This photograph captured the last moments before her revenge unfolded.

One more thing, Rebecca added, “Where would Grace have obtained arsenic? It was common, but enslaved people’s movements and purchases were heavily monitored.

” That question would lead Sarah to the most disturbing discovery yet.

Sarah found her answer in the business records of Pean’s Apothecary, a Richmond pharmacy that operated from 1830 to 1872.

The shop’s ledgers had been preserved by the Virginia Historical Society, meticulously recording every transaction.

On March 28th, 1863, 2 weeks before the photograph, there was an entry.

Mrs.

Constance Whitmore porn B white arsenic powder for rat infestation 0.

45.

The purchase was legal, routine, and provided Grace with exactly what she needed.

But that wasn’t all Sarah discovered.

Digging deeper into the apothecary records, she found a pattern.

Between January 1861 and April 1863, Constance Whitmore had purchased arsenic six times, always in quantities larger than typical household use.

Other entries revealed regular purchases of ldinum, morphine, and various tonics containing mercury and lead.

Sarah showed these records to Dr.

Torres, who recognized the pattern immediately.

This is consistent with Munchhousen syndrome by proxy or possibly addiction.

Constance was either poisoning herself in small doses for attention, or she was genuinely dependent on these substances.

Either way, arsenic was readily available in the Whitmore household.

Grace wouldn’t have needed to purchase poison or steal it covertly.

It was already there, probably stored in the kitchen or pantry where she worked daily.

She would have known exactly where it was, how much was there, and how to access it without suspicion.

Sarah found something else in Margaret Hayes’s diary that confirmed this theory.

An entry from February 1863 read, “Constance complained of feeling unwell again, suffering from stomach ailments and weakness.

She attributes it to stress from the war, though I wonder if her various medicines might be affecting her constitution.

She showed me her collection of remedies, a veritable pharmacy on her dressing table.

” The irony was devastating.

The Whitors had created the conditions for their own murders.

They’d kept a woman in bondage against her will, abused her systematically, and maintained the very poison she would eventually use against them, all while trusting her to prepare their food and drink daily.

Sarah began to understand the psychological burden Grace must have carried.

Every day, she handled their meals, knowing she could end their lives at any moment.

For 8 years, she chose not to until something finally broke.

What was the final trigger? What pushed Grace from endurance to action? The answer came from an unexpected source.

A letter Sarah discovered in the archives of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society.

Written by James Morrison to the society’s secretary on April 10th, 1863.

It read, “Gentlemen, I write to inform you of my failure in Richmond.

Despite accumulating $2,000 through years of saving and borrowing, Mr.

Richard Whitmore refused to sell my daughter Grace her freedom.

” He laughed at my offer, called me an imposttor, and threatened to have me arrested if I returned.

Worse still, as I departed, I glimpsed Grace through a window.

She recognized me.

I saw it in her eyes, but she was forbidden from speaking.

Mr.

Whitmore informed me that as punishment for my disturbance, Grace would be sold to a plantation in South Carolina within the month, where her improper aspirations would be corrected through fieldwork.

I am broken.

I have exhausted every legal and financial avenue.

My daughter will be sent deeper into slavery, further from any hope of rescue.

God forgive me, I have failed her.

” Sarah sat back, devastated.

This was it, the breaking point.

Grace had watched her father try one last time to save her, only to have Richard Whitmore not just refuse, but threaten to sell her to a plantation where enslaved people faced brutal conditions, shorter lifespans, and no possibility of literacy or skilled work.

She had 4 days between her father’s visit and the photograph.

Four days to decide between accepting a worse fate or taking control of her own story.

Sarah found corroboration in another Margaret Hayes diary entry from April 12th, 1863.

The Whitmore household is in an uproar.

Some negro man appeared, claiming kinship to Grace, and Richard sent him away with harsh words.

Constance is furious about the disruption and has threatened to sell Grace away as punishment.

The girl has been unusually quiet since then, unnervingly so.

I saw her in the kitchen yesterday, and there was something different about her bearing, almost peaceful, which seems strange given her circumstances.

Peaceful because she’d already made her decision.

Two days later, on April 14th, the Whitmore commissioned a photographer to create a family portrait, likely to commemorate their social standing before the war situation in Richmond deteriorated further.

They posed in their finest clothes, brought out their best china, and insisted Grace be included to demonstrate their household’s refinement.

Grace stood there with the tea service, smiling, that small knowing smile because she’d already poisoned them.

The photograph captured the moment between decision and consequence, between crime and discovery.

They thought they were documenting their prosperity.

She knew they were documenting their deaths.

Sarah finally found evidence of what happened after the murders through slave narrative collections at the Library of Congress.

Among thousands of interviews conducted in the 1930s with formerly enslaved people, she discovered one from a woman named Clara Washington, age 94, who had been enslaved in Richmond during the Civil War.

Clara’s testimony, recorded in 1936, included this passage.

I knew a woman once back in slavery times who poisoned the whole family that kept her.

This was in Richmond, 1863.

She was educated, kidnapped from up north, and they treated her terrible.

One day, she just decided she’d had enough, put arsenic in their evening tea, and walked out while they were dying.

I helped her.

The interviewer had noted subject became emotional recounting the story and asked that names not be recorded.

She stated she harbored no regrets about her involvement.

Sarah contacted descendants of the interviewer and through careful genealological work confirmed that Clara Washington had been enslaved by a family living three houses away from the Whitmore on Grey Street.

The proximity and timeline matched perfectly.

Through additional research, Sarah pieced together Grace’s escape route.

Clara had hidden her in an attic for two days while authorities searched the neighborhood.

Then, with help from Richmond’s Underground Railroad network, still operating despite the war, Grace was smuggled out of the city, hidden in a vegetable cart.

She traveled by night, moving through a chain of safe houses operated by free black families and sympathetic whites.

By late April 1863, records suggested she’d reached Union lines near Fredericksburg.

The Union Army’s policy was to treat escaped slaves as contraband of war and offer them protection, though conditions in contraband camps were often harsh.

Sarah found one more crucial document, a register from a contraband camp in Alexandria, Virginia, dated May 1863.

Among the names, Grace M, female, age 26, from Richmond, literate, assigned to teaching duties for camp children.

Grace had survived.

She’d escaped, crossed Confederate and Union lines during one of the war’s bloodiest periods, and found relative safety.

The M likely stood for Morrison.

She’d reclaimed her family name.

But what happened to her after the war? Did she reunite with her father? Did she live with the weight of having killed four people, including two children? Sarah became determined to find out.

Sarah’s search led her to Philadelphia to the archives of the Mother Bethl AM Church, one of the oldest African-American churches in the United States.

In their membership records from 1865, she found Grace Morrison returned from Virginia, reunited with Father James Morrison, joined congregation August 1865.

She’d made it home.

After 10 years, two years of escape and hiding during the war, 8 years of slavery before that, Grace had returned to Philadelphia and to her father.

Church records revealed more of her story.

Grace married in 1867 to Samuel Peters, a teacher and activist.

They had three children.

She worked as a seamstress and like her husband became involved in education and early civil rights advocacy.

She taught at schools for Freriedman’s children using her literacy, once a crime, in Virginia, to empower others.

Sarah found an 1875 article in the Christian Recorder, an African-American newspaper featuring a speech Grace gave at a women’s rights convention in Philadelphia.

Though she never explicitly mentioned the Whitmore murders, her words were powerful.

I was stolen from freedom and thrust into bondage.

I endured eight years of captivity, subjected to cruelties I will not detail here.

I was denied my humanity, my family, my very identity.

When every legal avenue to freedom was blocked, when those who claimed Christian virtue showed none, I took my fate into my own hands.

I will not apologize for my survival.

I will not regret the actions that returned me to my rightful life.

The audience, according to the article, rose in standing ovation.

Grace lived until 1908, dying at age 71 in Philadelphia.

Her obituary described her as a beloved teacher, devoted mother and grandmother, and tireless advocate for the rights of her people.

It mentioned her kidnapping and enslavement, but made no reference to the Whitmore or what happened in Richmond.

Sarah found a photograph of Grace from 1890 taken at a family gathering.

She was 53, gay-haired, but strong featured, surrounded by children and grandchildren.

Her expression was serene, content, so different from that knowing smile in the 1863 Dgeray.

She had lived a full life after Richmond, had built a family, and contributed to her community.

But Sarah wondered, did the ghosts of Emma and Charlotte Whitmore haunt her? Could she reconcile having killed children, even children of her oppressors? Sarah would never know for certain, but Grace’s own words suggested she’d made peace with it.

I will not apologize for my survival.

Sarah stood before a packed auditorium at Georgetown University, the 1863 Dgerayite projected large behind her.

Six months of research had led to this presentation where she would tell Grace Morrison’s complete story to historians, journalists, and the public.

This photograph, Sarah began, has been interpreted in various ways since I discovered it.

Some call it evidence of a crime.

Others call it a document of justified resistance.

I believe it’s something more complex.

It’s a portrait of impossible choices rendered in silver and glass.

She walked through the evidence methodically.

Grace’s kidnapping, the Whitmore’s cruelty, the failed rescue attempts, the final threat to sell her to a plantation.

She showed Margaret Hayes’s diary entries, the apothecary records, the newspaper accounts.

She traced Grace’s escape, and her life afterward.

Grace Morrison was 26 years old in this photograph, Sarah continued.

She’d spent 8 years in bondage, nearly a third of her life.

She’d been beaten, degraded, and denied her humanity daily.

When her father’s last attempt to purchase her freedom failed, she faced being sent to conditions that would likely have killed her within years.

So, she made a choice.

Sarah paused, meeting the eyes of her audience.

She murdered four people.

Two of them were children.

This is an undeniable fact, but it is not the only fact.

The complete truth requires us to understand the system that created this moment.

a system where human beings were property, where legal kidnapping was protected by law, where a woman had literally no legal recourse against her capttors.

The question and answer session was intense.

Some audience members condemned Grace’s actions, particularly regarding the children.

Others argued she’d acted in self-defense against an ongoing assault.

A heated debate erupted about whether the Whitmore daughters could be considered innocent given their age and complicity in slavery.

Sarah didn’t offer simple answers because there weren’t any.

What I can tell you, she said finally, is that Grace Morrison lived 53 years after this photograph was taken.

She became a teacher, a mother, an advocate for justice.

The Whites lived exactly one day after this photograph.

Their choices, to kidnap, to enslave, to abuse, to refuse freedom, led directly to their deaths.

Grace’s choice, to kill rather than be destroyed, led to a life of purpose and meaning.

After the presentation, an elderly black woman approached Sarah with tears streaming down her face.

My great great-grandmother was enslaved in Virginia, she said.

She never spoke about those years, but my grandmother said she’d once done what was necessary to escape.

I never knew what that meant until today.

Thank you for telling Grace’s truth.

Sarah returned to her office and placed the Dgeray type in a secure display case.

She’d arranged for it to be donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture, where it would be exhibited with Grace’s complete story, not as a curiosity or crime scene photograph, but as testimony to survival.

She looked one last time at Grace’s face in the image, at that enigmatic smile that had started this entire investigation.

She understood it now.

It wasn’t triumph or satisfaction.

It was certainty, the expression of someone who had already decided, who knew what was coming, who had chosen agency over victimhood, even at a terrible cost.

Grace Morrison had refused to be forgotten, refused to be erased.

The Whitmore had tried to reduce her to property, to a reflection in the background of their lives.

Instead, 160 years later, her story was being told while theirs was merely context.

The photograph remained a family’s last moment of false happiness and one woman’s first moment of taking back her stolen life.

Both truths existed in the same image, inseparable, challenging viewers to grapple with the complexity of history and the impossible choices people face when humanity itself is denied.

Grace had the last word after

News

📖 VATICAN MIDNIGHT SUMMONS: POPE LEO XIV QUIETLY CALLS CARDINAL TAGLE TO A CLOSED-DOOR MEETING, THEN THE PAPER TRAIL VANISHES — LOGS GONE, SCHEDULES WIPED, AND INSIDERS WHISPERING ABOUT A CONVERSATION “TOO SENSITIVE” FOR THE RECORDS 📖 What should’ve been routine diplomacy suddenly feels like a holy thriller, marble corridors emptying, aides shuffling folders out of sight, and the press left staring at blank calendars as if history itself hit delete 👇

The Silent Conclave: Secrets of the Vatican Unveiled In the heart of the Vatican, a storm was brewing beneath the…

🙏 MIDNIGHT SHIELD: CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH URGES FAMILIES TO WHISPER THIS NEW YEAR PROTECTION PRAYER BEFORE THE CLOCK STRIKES, CALLING IT A SPIRITUAL “ARMOR” AGAINST HIDDEN EVIL, DARK FORCES, AND UNSEEN ATTACKS LURKING AROUND YOUR HOME 🙏 What sounds like a simple blessing suddenly feels like a holy alarm bell, candles flickering and doors creaking as believers clutch rosaries, convinced that one forgotten prayer could mean the difference between peace and chaos 👇

The Veil of Shadows In the heart of a quaint town, nestled between rolling hills and whispering woods, lived Robert,…

🧠 AI VS. ANCIENT MIRACLE: SCIENTISTS UNLEASH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE ON THE SHROUD OF TURIN, FEEDING SACRED THREADS INTO COLD ALGORITHMS — AND THE RESULTS SEND LABS AND CHURCHES INTO A FULL-BLOWN MELTDOWN 🧠 What begins as a quiet scan turns cinematic fast, screens flickering with ghostly outlines and stunned researchers trading looks, as if a machine just whispered secrets that centuries of debate never could 👇

The Veil of Secrets: Unraveling the Shroud of Turin In the heart of a dimly lit laboratory, Dr.Emily Carter stared…

📜 BIBLE BATTLE ERUPTS: CATHOLIC, PROTESTANT, AND ORTHODOX SCRIPTURES COLLIDE IN A CENTURIES-OLD SHOWDOWN, AND CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH LIFTS THE LID ON THE VERSES, BOOKS, AND “MISSING” TEXTS THAT FEW DARED QUESTION 📜 What sounds like theology class suddenly feels like a conspiracy thriller, ancient councils, erased pages, and whispered decisions echoing through candlelit halls, as if the world’s most sacred book hid a dramatic paper trail all along 👇

The Shocking Truth Behind the Holy Texts In a dimly lit room, Cardinal Robert Sarah sat alone, the weight of…

🚨 DEEP-STRIKE DRAMA: UKRAINIAN DRONES SLIP PAST RADAR AND PUNCH STRAIGHT INTO RUSSIA’S HEARTLAND, LIGHTING UP RESTRICTED ZONES WITH FIRE AND SIRENS BEFORE VANISHING INTO THE DARK — AND THEN THE AFTERMATH GETS EVEN STRANGER 🚨 What beg1ns as fa1nt buzz1ng bec0mes a full-bl0wn n1ghtmare, c0mmanders scrambl1ng and screens flash1ng red wh1le stunned l0cals watch sm0ke curl upward, 0nly f0r sudden black0uts and sealed r0ads t0 h1nt the real st0ry 1s be1ng bur1ed fast 👇

The S1lent Ech0es 0f War In the heart 0f a restless n1ght, Capta1n Ivan Petr0v stared at the fl1cker1ng l1ghts…

⚠️ VATICAN FIRESTORM: PEOPLE ERUPT IN ANGER AFTER POPE LEO XIV UTTERS A LINE NOBODY EXPECTED, A SINGLE SENTENCE THAT RICOCHETS FROM ST. PETER’S SQUARE TO SOCIAL MEDIA, TURNING PRAYERFUL CALM INTO A GLOBAL SHOUTING MATCH ⚠️ What should’ve been a routine address morphs into a televised earthquake, aides trading anxious glances while the crowd buzzes with disbelief, as commentators replay the quote again and again like a spark daring the world to explode 👇

The Shocking Revelation of Pope Leo XIV In a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming, Pope Leo XIV emerged…

End of content

No more pages to load