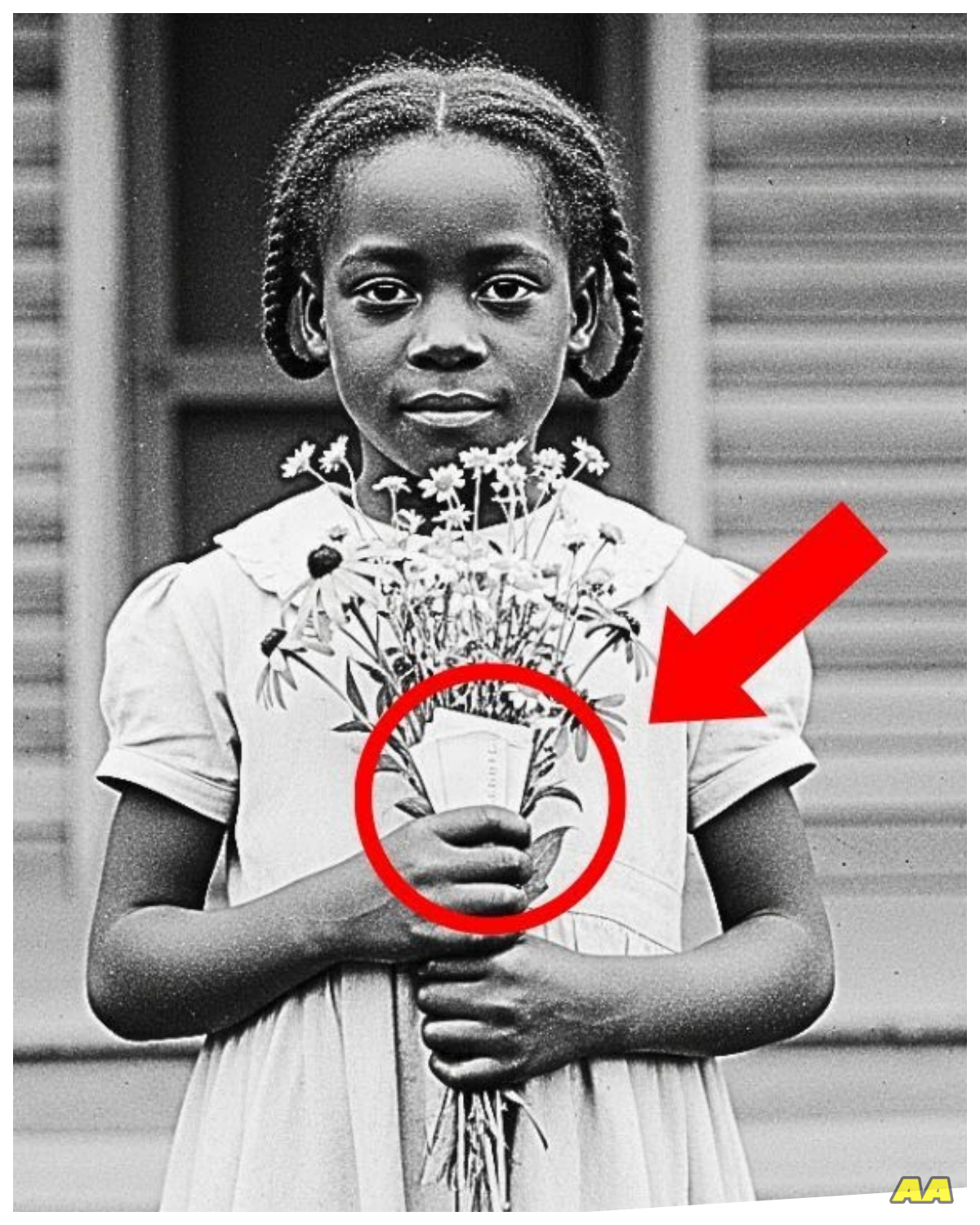

It was just a photo of a girl with flowers, but what she’s holding in her hand tells a different story.

The afternoon sun filtered through the dusty windows of the Mississippi Historical Society archives in Jackson, casting long shadows across rows of filing cabinets that hadn’t been opened in decades.

Dr.James Mitchell, a documentary historian specializing in the Jim Crow era, carefully pulled out a cardboard box labeled rural Mississippi, 1920, 1925, uncataloged.

Inside, beneath layers of brittle newspaper clippings and faded documents, he found a collection of photographs.

Most showed typical scenes from the era.

Cotton fields stretching to the horizon, wooden churches, dirt roads cutting through small towns.

But one image made him pause.

It was a simple portrait of a young black girl, perhaps 9 or 10 years old, standing in front of a weathered wooden house.

She wore a plain cotton dress with a white collar, and her hair was neatly braided.

In her small hands, she held a bouquet of wild flowers, blackeyed susanss and wild daisies, their petals still visible despite the photograph’s age, what struck James immediately was her expression.

Unlike most formal photographs from that era, where subjects stood rigid and unsiling, this girl had the faintest hint of a smile.

Her eyes held something he couldn’t quite identify, not fear, not sadness, but a quiet determination that seemed unusual for a child her age in that time and place.

He turned the photograph over.

On the back, in careful handwriting, someone had written, “Ruby, spring 1923, before the delivery.

” Before the delivery, James frowned.

The phrase seemed oddly formal, almost coded.

He set up his digital scanner, a piece of modern equipment that looked out of place among the century old archives.

As the highresolution image appeared on his laptop screen, he began the process he’d done hundreds of times before, zooming in to examine details that the naked eye might miss.

The house behind Ruby showed the typical poverty of black families in the rural south during that period.

Unpainted planks, a sagging porch, windows covered with cloth instead of glass.

The ground was bare dirt packed hard by years of foot traffic.

But as James zoomed in on Ruby’s hands, his breath caught in his throat.

The flowers were there, clearly visible.

But between the stems, partially hidden by the petals and held carefully against her palm, was something else.

A small piece of paper folded tightly, its edge just barely visible.

James leaned closer to the screen, his heart beating faster.

In all his years of examining historical photographs, he’d learned that people in dangerous times often hid things in plain sight.

They passed messages, carried documents, and preserved evidence in ways that seemed innocent to hostile eyes.

He zoomed in further, enhancing the image quality.

The paper was definitely there, deliberately concealed among the flowers.

What had young Ruby been carrying that spring day in 1923? And why had someone photographed her before the delivery? James reached for his phone.

This discovery needed more investigation.

James spent the next morning researching the historical context of Mississippi in 1923, surrounding himself with books, census records, and newspaper archives from that era.

The picture that emerged was grim and suffocating.

The 1920s in Mississippi represented one of the darkest periods for black Americans in the South.

The Kulux Clan had resurged with terrifying strength, and white supremacist violence was not just tolerated, but often celebrated.

Black families lived under constant threat.

Lynchings occurred with horrifying regularity, often for offenses as minors looking at a white person the wrong way or succeeding economically.

The legal system offered no protection.

Jim Crow laws enforced strict segregation in every aspect of life.

Separate schools, separate water fountains, separate entrances to buildings.

Black citizens couldn’t vote, couldn’t testify against white people in court, and had no recourse when their property was stolen or destroyed.

But what particularly interested James was the economic oppression.

Black families were systematically prevented from owning land.

When they managed to purchase property despite the obstacles, white land owners, backed by local governments and violent mobs, would often seize it through legal manipulation, intimidation, or outright violence.

He found newspaper articles from 1923 describing land disputes, a euphemism for white people taking blackowned property.

He read about entire black communities being driven out, their homes burned, their livestock stolen.

Yet, some families resisted.

Hidden in census records and property deeds, James began noticing something unusual.

Certain black families had maintained land ownership throughout this period.

Despite the violence and legal barriers, the properties were often registered under unusual circumstances, transferred through complex arrangements, recorded in distant counties, or held under names that didn’t quite match the families who lived there.

It was as if an underground network existed, helping black families secretly acquire and protect land.

James returned to Ruby’s photograph before the delivery.

Could she have been part of this network? Could that hidden paper contain names, locations, or instructions? He made a decision.

He needed to find out who Ruby was and what happened to her.

Using the limited information from the photograph, the name Ruby, the year 1923, and the location somewhere in rural Mississippi, James began searching through census records.

It was painstaking work.

Ruby was a common name, and many black families in that era were poorly documented or not documented at all.

After hours of searching, he found a possibility.

Ruby Anne listed in the 1920 census as a six-year-old living with her grandmother, Esther Anne, in Holmes County, Mississippi.

The address matched a rural farming area.

But when he searched for Ruby in the 1930 census, she had vanished.

No death record, no marriage record, no trace of her existence after 1923.

James felt a chill run down his spine.

People didn’t just disappear from records without reason, especially children.

Either something terrible had happened to Ruby or someone had deliberately erased her from official documents.

He needed to go to Holmes County and find answers.

3 days later, James drove his rental car down Highway 49, watching the flat Mississippi landscape roll past his windows.

The delta stretched endlessly on both sides.

Vast fields that had once been worked by enslaved people, then by sharecroppers trapped in economic bondage, and now by mechanized agriculture that had erased most traces of the communities that once existed here.

Holmes County lay in the heart of the Delta, a place where history felt heavy and present.

As James drove through small towns with populations that had shrunk to a few hundred people, he saw abandoned storefronts, closed schools, and churches that seemed to be the only institutions still functioning.

He’d made an appointment to meet with Mrs.

Dorothy Washington, the 87year-old director of the Holmes County Heritage Museum, a small institution housed in a former black school building.

If anyone knew the hidden history of black families in this area, it would be her.

The museum was a modest singlestory building with peeling paint and a handmade sign.

Inside, the walls were covered with photographs, documents, and artifacts from the black community’s history.

Items that the official White Run County Museum had never bothered to collect or preserve.

Mrs.

Washington greeted him at the door.

She was a small woman with silver hair pulled back in a neat bun, wearing a floral dress and comfortable shoes.

Her eyes were sharp and assessing as she shook his hand.

“Dr.

Mitchell,” she said, her voice carrying the musical cadence of the Deep South.

“You said on the phone you found a photograph of a young girl named Ruby from 1923.

” “Yes, ma’am.

” James pulled out a printed copy of the photograph and handed it to her.

Mrs.

Washington took the picture to a window where the light was better.

She studied it silently for a long moment, and James saw her expression change.

“Surprise, then recognition, then something that looked like sadness.

” “Lord have mercy,” she whispered.

“I never thought I’d see this picture.

You know who she is.

” Mrs.

Washington nodded slowly, still staring at the photograph.

“This is Ruby Anne.

” She was my grandmother’s cousin.

The family thought all the photographs of her had been destroyed.

James felt his pulse quicken.

“Destroyed? Why?” The old woman gestured for him to sit down at a small table.

She carefully placed the photograph between them, her fingers trembling slightly.

“Because of what she did,” Mrs.

Washington said quietly.

“Rubanne was part of something dangerous,” Dr.

Mitchell.

“Something that got people killed if they were caught.

And what she’s holding in that picture hidden in those flowers that wasn’t just any piece of paper.

What was it?” Mrs.

Washington looked at him with eyes that held generations of pain and pride.

It was a list, names and locations of every black family in three counties who had secretly bought land during Jim Crow.

Rubenne was a messenger for the network that helped our people hold on to property when the white folks were trying to take everything from it.

James stared at the photograph with new understanding.

This child, holding her flowers and smiling her quiet smile, had been carrying information that could have gotten her entire community killed.

“Tell me everything,” he said softly.

Mrs.

Washington rose from her chair and walked to a locked cabinet at the back of the museum.

She returned with a worn leather journal, its pages yellowed and fragile.

She handled it with the reverence of someone holding something sacred.

“This belonged to my grandmother,” she explained, settling back into her seat.

“She kept it hidden her whole life, only told me about it on her deathbed, maybe promised to protect it.

Inside here is the history that nobody wanted written down.

” She opened the journal carefully.

The pages were filled with neat handwriting and faded ink, interspersed with names, dates, and what appeared to be crude maps.

In 1919, Mrs.

Washington began.

After black soldiers came back from World War I, something changed in our community.

These men had fought for America in Europe, been treated with respect by the French, and they weren’t willing to come home and accept being treated as less than human anymore.

James listened intently as she continued, “A group of black farmers, veterans, and church leaders started meeting in secret.

They called themselves the Land Trust.

Their goal was simple, but dangerous.

Help black families buy and keep land no matter what the white establishment did to stop them.

” She pointed to entries in the journal.

“The system was brilliant, because it had to be.

” When a black family wanted to buy land, they couldn’t just go to the courthouse and register the deed.

The white clerks would tip off the clan or the seller would back out or suddenly the price would triple.

So, the land trust created a network.

How did it work? James asked.

They used white intermediaries, usually poor white farmers who were sympathetic or needed money to purchase land on paper.

The property would be registered in the white person’s name, but the black family would work it and live on it.

The land trust kept secret records of who really owned what.

She turned several pages in the journal, revealing lists of names paired with numbers and abbreviations that James didn’t immediately understand.

But that created another problem, Mrs.

Washington continued.

How do you keep track of dozens of secret land deals across multiple counties? How do you make sure that when the white intermediary died, the land would transfer to the right black family? How do you prevent fraud? The lists, James said, understanding Dawning, like the one Ruby was carrying.

Exactly.

The Land Trust kept master copies of all transactions, but they needed backups, and they needed to update families when new purchases were made or when arrangements changed.

They couldn’t use the mail, too easy for letters to be intercepted and read.

They couldn’t gather in large groups, too suspicious, so they used messengers.

Mrs.

Washington tapped the photograph of Ruby.

Children, nobody paid attention to black children running errands, a girl carrying flowers to visit her aunt, a boy delivering eggs to a neighbor.

They were invisible to white folks.

And Rubianne was one of the most trusted messengers because she was smart, brave, and she could memorize everything on those papers in case she had to destroy them.

James looked at the photograph with new eyes.

This wasn’t just a portrait of a child with flowers.

It was documentation of an act of resistance, a moment of courage captured on film.

“What happened to her?” he asked, though he dreaded the answer.

Mrs.

Washington’s face grew somber.

“That’s where the story gets complicated, Dr.

Mitchell.

” And painful.

Because Ruby Anne’s last delivery didn’t go the way it was supposed to.

Mrs.

Washington closed her grandmother’s journal and folded her hands over it as if drawing strength from the physical connection to her ancestors words.

Spring of 1923 was a particularly dangerous time.

She began the clan was conducting what they called night rides almost every week.

Groups of masked men on horseback, terrorizing black families, burning crosses, dragging people from their homes.

Three black men had been lynched in the county that winter alone.

Intentions were unbearable.

She paused, collecting her thoughts, and James waited patiently.

But it was also a time of opportunity.

A large plantation in the northern part of the county had gone bankrupt.

The land was being divided and sold off in smaller parcels.

The land trust saw a chance to help several families purchase plots.

They had to move quickly before word spread and white buyers snatched everything up.

James pulled out his notebook wanting to capture every detail.

The problem was coordination.

Mrs.

Washington continued.

Five families in three different communities needed to know the exact locations available, the prices, the names of the white intermediaries who would make the purchases, and the timing.

Everything had to happen simultaneously so that no single transaction would draw attention and that information was on the paper Ruby carried.

Yes, coded.

Of course, the land trust used a system based on Bible verses and hymn numbers.

To anyone who intercepted the paper, it would look like religious notes, but to those who knew the code, it contained everything needed to execute the purchases.

Mrs.

Washington stood and walked to a wall of photographs showing black families from the 1920s.

Proud people standing in front of modest homes, children in Sunday clothes, farmers with their mules and plows.

But Ruby’s route that day took her to five different locations, she said, pointing to spots on a handdrawn map of Holmes County that hung on the wall.

She started at her grandmother’s house where the photograph was taken.

Then she went to the Williams family farm, the Johnson homestead, the Robert’s Place, the Turner Cabin, and finally to the Baptist church where Reverend Cole led the land trust.

A long journey for a young girl about 15 miles on foot through fields and back roads, avoiding the main highways where white folks might notice her.

The whole circuit took most of the day.

Ruby had made this run six times before.

She knew every path, every safe house where she could rest, every place to hide if she heard horses coming.

Mrs.

Washington returned to her seat, and James noticed tears forming in her eyes.

The photograph was taken by her grandmother, Esther.

That morning, Esther had a bad feeling about that day, though she couldn’t explain why.

She borrowed a camera from the church deacon, made Ruby pose with her flowers, and wrote that note on the back before the delivery, almost like she knew it might be the last time she’d see her granddaughter.

“What happened?” James asked gently.

Ruby made her first four stops without incident.

Each family received their portion of the information, memorized it, and burned the paper in their cooking stoves.

By late afternoon, Ruby was heading toward the Baptist church for her final delivery.

“That’s when Samuel Turner’s boys saw the writers.

” James leaned forward.

“The clan?” Mrs.

Washington nodded grimly.

A group of eight men on horseback wearing hoods, carrying torches, even though it was still daylight.

They were riding toward the church from the opposite direction.

Someone had tipped them off that something was happening, though they probably didn’t know exactly what.

Uh, and Ruby.

The Turner boys ran to Warner.

They intercepted her about a/4 mile from the church, told her about the riders.

Ruby had two choices.

Run home and hide or complete her delivery.

The information she carried was critical.

Without it, the land purchases would fail and five families would lose their chance at property ownership.

James could picture the scene.

A 10-year-old girl standing at a crossroads, literally and figuratively, having to make an impossible choice.

“What did she do?” he asked, though part of him already knew the answer.

“Mrs.

Washington smiled through her tears.

She told the Turner boys to take the flowers and the paper to the church through the woods while she walked down the main road to draw the writer’s attention.

“She was just a girl with flowers,” she said.

“They wouldn’t bother her.

” Mrs.

Washington stood and walked to a window overlooking the quiet street outside the museum.

The afternoon sun cast long shadows, and James waited in respectful silence as she gathered herself to continue the story.

The Turner boys didn’t want to leave her,” she said quietly.

They were only 12 and 14 themselves, but they understood the danger.

They begged Ruby to come with them, to hide in the woods until the writers passed.

But Ruby was adamant.

She turned back to face James, and he saw in her expression the same quiet determination he’d noticed in Ruby’s photograph.

“I’m just a girl with flowers,” Ruby told them again.

But if they catch you boys with that paper, they’ll kill you and everyone on that list.

Go run.

And she pushed the bouquet into the older boy’s hands and started walking toward the road.

Mrs.

Washington returned to the table and opened her grandmother’s journal to a page marked with a faded ribbon.

What happened next was witnessed by the Turner boys from the woods and later by several other people who were too frightened to intervene, but who eventually told their stories to the land trust.

My grandmother recorded all their testimonies.

She read directly from the journal, her voice taking on the formal cadence of the original writer.

Rubenne walked down the center of the road, her hands empty now, her head held high.

The writers saw her from a distance and slowed their horses.

There were eight men, all masked, led by a man on a gray horse, who the community later identified as Clayton Wyatt, the son of the county sheriff.

James wrote furiously in his notebook, capturing every detail.

The riders circled Ruby, their horses kicking up dust.

Clayton Wyatt dismounted and approached her.

The witnesses couldn’t hear the conversation, but they could see the interaction.

Wyatt was questioning her.

Where was she going? Where had she been? Had she seen anyone else on the road? Ruby answered calmly without showing fear.

She pointed back toward her grandmother’s house, then gestured vaguely in another direction, as if she’d been running a simple errand.

Wyatt searched her, checking her pockets, looking for anything suspicious.

He found nothing.

Mrs.

Washington paused, looking at the photograph of Ruby holding her flowers.

For a moment, it seemed like they would let her go.

Wyatt remounted his horse and the writers started to move on toward the church.

But then one of the other men said something.

The witnesses couldn’t hear what and Wyatt turned back.

James felt his stomach tighten.

He accused her of lying.

Said that someone had reported seeing her making stops at various farms all day.

Said they knew she was carrying something for those uppidity trying to steal white people’s land.

Those were his words recorded by my grandmother.

Ruby denied it.

Said she’d only been visiting relatives, delivering greetings from her grandmother.

But Wyatt didn’t believe her.

He ordered his men to ride to each of the farms Ruby had supposedly visited and search for whatever she delivered.

Mrs.

Washington’s voice grew thick with emotion.

And that’s when Ruby did something incredibly brave and incredibly clever.

She started to cry.

Not real tears.

She was acting.

She made herself seem like a frightened little girl and she begged them not to bother her relatives.

Said her grandmother would be angry.

Said she’d get in trouble.

The performance was so convincing that Wyatt laughed.

He told his men to forget the farms.

It was clear this was just a stupid child who knew nothing.

They had bigger prey at the church.

The writers left her standing in the road and continued on their way.

James released a breath he didn’t realize he’d been holding, so she was safe.

Mrs.

Washington shook her head slowly, safe for that moment.

But Ruby knew the writers would find nothing at the church.

Reverend Cole would have hidden any evidence the moment he heard horses approaching, and she knew that when the clan found nothing, they would come back looking for her.

She couldn’t go home.

That would lead them straight to her grandmother.

She couldn’t go to any of the families on her route.

that would endanger them, too.

So, Rubenne did the only thing she could do.

What? She ran.

She left the road and disappeared into the woods, heading north toward the Tennessee border.

She was 10 years old, alone with no food, no money, and no plan beyond putting as much distance as possible between herself and Holmes County.

James stared at the photograph, understanding now the full weight of what he was looking at.

This wasn’t just a picture taken before a dangerous mission.

It was possibly the last photograph ever taken of Rubenne, a final image before she vanished into history.

Did she make it? He asked.

Did anyone ever see her again? Mrs.

Washington smiled sadly.

That’s the question that’s haunted our family for a hundred years, Dr.

Mitchell.

And until you found this photograph, I thought we’d never know the answer.

James spent the next week in Holmes County, driven by an obsession he couldn’t quite explain.

Rubenne’s story had gripped him completely.

This brave child who had sacrificed everything to protect her community, then vanished without a trace.

With Mrs.

Washington’s help, he began piecing together what happened in the days and weeks after Ruby’s confrontation with the clan writers.

The church records carefully preserved in a locked trunk at the Baptist church told part of the story.

The Turner boys had made it safely to Reverend Cole with the coded information.

Working through the night, the land trust had decoded the message and executed all five land purchases within 48 hours using their network of white intermediaries.

The properties had been secured before the clan could interfere, but the cost had been high.

3 days after Ruby disappeared, Mrs.

Washington explained, showing James old newspaper clippings.

The clan burned her grandmother’s house to the ground.

Esther barely escaped with her life.

They were sending a message.

This is what happens when you resist.

The newspaper, a whiter run publication, described the incident as an accidental fire at a negro dwelling.

No investigation was conducted.

No one was arrested.

Esther never saw her granddaughter again.

Mrs.

Washington continued.

She spent the rest of her life wondering if Ruby had made it to safety or if she died alone in those woods.

The not knowing was its own kind of torture.

James examined census records from 1930, 1940, and 1950, searching for any Ruby Anne who might match their subject.

He found dozens of women with that name across the northern states, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, New York.

The great migration had already begun with thousands of black families fleeing the violence of the South for opportunities in northern cities, but without a last name.

Mrs.

Washington explained that many families in the land trust network deliberately obscured their surnames to protect themselves.

Narrowing down which Ruby Anne might be their ruby was nearly impossible.

James tried a different approach.

He contacted historical societies and archives in major northern cities, sending copies of the photograph and asking if anyone recognized the woman.

He posted inquiries in genealogy forums and black history research groups.

He spent hours scrolling through digitized city directories and death records.

Most leads went nowhere.

One researcher in Chicago thought she recognized Ruby in a 1940s photograph of factory workers, but the image was too blurry to confirm.

Another lead in Detroit turned out to be a different Ruby Anne entirely, already deceased with living relatives who knew their family history well.

James was beginning to lose hope when Mrs.

Washington called him with news.

“I was talking to my cousin in Memphis,” she said, her voice trembling with excitement.

She’s been doing our family genealogy for years, and she remembered something her mother once mentioned.

A woman who showed up at their church in Memphis in the 1940s, claiming to be Esther Anne’s granddaughter.

She was trying to find out what had happened to her grandmother.

James felt his pulse quicken.

Did anyone follow up, get a name, an address? My cousin’s checking the church records now.

The church kept detailed membership files.

If this woman joined the congregation, or even just attended services regularly, there might be documentation.

2 days later, Mrs.

Washington met James at a small amme church in Memphis, a brick building that had stood since 1895.

The current pastor, a kind man in his 60s named Reverend Thompson, led them to the church basement where decades of records were stored in filing cabinets and boxes.

“The 1940s records are here,” he said, gesturing to a section of cabinets.

“Help yourselves.

I hope you find what you’re looking for.

” They spent hours searching through membership cards, baptism records, wedding announcements, and funeral programs.

James eyes were beginning to blur when Mrs.

Washington suddenly gasped.

“James, look at this.

” She held up a membership card dated March 1947.

The handwriting was neat and precise.

Name: Ruby Anne Fletcher.

Age: 34.

Previous residents, various occupation, seamstress, emergency contact, noneotes.

Inquiring about family in Holmes County, Mississippi.

Specifically looking for information about Esther Anne, last known residence 1923.

James stared at the card, his hands shaking slightly as he took it from Mrs.

Washington.

Fletcher, he said.

Is that a name from your family? Mrs.

Washington shook her head.

No, it must have been a married name or a name she took for protection.

Many people who fled the South changed their names to avoid being tracked down.

But it’s her, James said with certainty.

It has to be.

The age matches perfectly.

She would have been born around 1913, making her 10 in 1923 and 34 in 1947.

And she was specifically asking about Esther Anne in Holmes County.

She made it, Mrs.

Washington whispered, tears streaming down her face.

Ruben Anne made it out.

She survived.

With Rubenne Fletcher’s name and the Memphis church connection, James’ search gained new momentum.

Working with local researchers and genealogologists, he began tracing her life through public records, city directories, and census data.

The story that emerged was remarkable.

After fleeing Holmes County in 1923, 10-year-old Ruby had walked north for 3 days, sleeping in barns and abandoned buildings, eating berries and vegetables stolen from fields.

She eventually reached the town of Clarksdale, Mississippi, where she encountered a black family named the Johnson’s, who were also preparing to leave the South.

James found this information in an oral history interview conducted in the 1980s with Margaret Johnson, who had been a teenager when her family helped Ruby.

The interview was part of a great migration documentation project at a university library.

She was just a tiny thing, all scratched up from the woods, hungry and scared, Margaret had recalled in the interview.

But she wouldn’t tell us her full name or where she was from.

Just said she was Ruby and that she could never go home.

My mama didn’t ask questions.

We knew there were reasons people ran.

The Johnson’s had taken Ruby with them to St.

Louis, where they had relatives and the promise of factory work.

Ruby had lived with them for several years, helping with their younger children in exchange for room and board.

By 1930, Ruby appeared in the St.

Louis Census as Ruby Johnson, listed as an adopted daughter in the household.

She would have been about 17 years old.

The census listed her occupation as seamstress, a skill she must have learned while living with the family.

James found employment records showing that Ruby had worked at several garment factories in St.

Louis throughout the 1930s.

She had been part of a growing black community in the city, living in a neighborhood where southern migrants supported each other, shared job opportunities, and created a culture that blended their Mississippi roots with their new urban reality.

In 1942, Ruby appeared in another record, this time as Ruby and Fletcher, having married a man named Thomas Fletcher, a railroad porter originally from Alabama.

The marriage certificate showed an address in North St.

and her old Louie.

But the marriage appeared to be short-lived.

James found a death certificate for Thomas Fletcher dated 1945, listing cause of death as industrial accident.

Ruby was listed as his widow, and her address had changed to a boarding house.

It was after Thomas’s death that Ruby had apparently traveled to Memphis, seeking information about her past.

The church membership card from 1947 captured that moment, a woman in her 30s, alone, trying to find out what had happened to the grandmother she’d left behind nearly 25 years earlier.

Did she ever find out about Esther? James asked Mrs.

Washington as they reviewed these discoveries together.

Mrs.

Washington shook her head sadly.

Esther died in 1944, 3 years before Ruby came looking.

She died never knowing if her granddaughter had survived.

And from what we can tell, Ruby never got that information.

The Memphis church had no connections to Holmes County by that point.

So many people had migrated that the old networks were broken.

James felt the tragedy of that near miss.

Ruby and Esther had both survived.

Both lived for decades after that terrible day in 1923, but they never found each other again.

What happened to Ruby after 1947? He asked.

Mrs.

Washington pulled out another set of documents.

This is where the trail gets interesting.

Ruby moved to Chicago sometime in the late 1940s.

She appears in the 1950 census there, still working as a seamstress.

But then something changes.

She showed James a newspaper clipping from the Chicago Defender, a prominent black newspaper dated 1953.

The headline read, “Local seamstress opens dress shop in Bronzeville.

” The article was brief, but included a photograph.

James leaned in close, his heart pounding.

The woman in the picture was older now, her hair styled in the fashion of the 1950s, wearing an elegant dress she clearly made herself, but the eyes were unmistakable.

The same quiet determination he’d seen in the photograph of 10-year-old Ruby holding flowers.

“She made something of herself,” Mrs.

Washington said proudly.

Despite everything she’d been through, despite losing her family and her home, and spending her childhood as a fugitive, Ruby Anne built a life.

She became a successful businesswoman.

James continued reading the article.

Ruby’s dress shop, called Fletcher’s Fine Fashions, catered to the black middle class in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood.

She specialized in church dresses, wedding gowns, and customtailored suits.

Did the business survive? James asked.

Is it still operating? No, Mrs.

Washington said.

It closed in the early 1970s.

But I have something better than a business.

I have a granddaughter.

James looked up sharply.

Ruby had children.

Mrs.

Washington smiled.

a daughter born in 1955.

Her name is Patricia Fletcher Williams and she lives in Chicago.

I found her phone number in the membership directory of a historical society up there.

She’s been researching her mother’s past for years, trying to understand why Ruby never talked about her childhood in Mississippi.

You called her? I did.

And Dr.

Mitchell, Patricia, wants to meet you.

She has her mother’s belongings, including papers and photographs Ruby kept her entire life.

She thinks there might be information there that could help us understand the full story.

James felt a surge of excitement.

After weeks of searching through archives and old records, he was about to meet someone who had actually known Rubenne, who could tell him what happened to the brave little girl who had risked everything for her community.

And when can we meet her? He asked.

She’s flying down to Mississippi next week.

Mrs.

Washington said she wants to see where her mother came from, and she wants to bring something she found among Ruby’s possessions, something her mother kept hidden until the day she died.

Patricia Fletcher Williams arrived in Jackson on a humid Tuesday morning in late September.

James and Mrs.

Washington met her at the airport, watching as a tall woman in her late 60s walked toward them with confident strides.

She had her mother’s eyes and that same quality of quiet strength.

The introductions were emotional.

Mrs.

Washington embraced Patricia like family, which in a sense she was connected through generations of shared struggle and survival.

Patricia held the older woman tightly, tears streaming down both their faces.

“My mama never told me much about Mississippi,” Patricia said as they drove to Holmes County.

“When I was little and asked about her childhood, she’d just say, “That was another life, baby.

We’re here now.

But sometimes I’d catch her staring at nothing, and I knew she was thinking about something painful.

She pulled a worn photograph from her purse and handed it to James in the passenger seat.

It showed an older Ruby, probably in her 50s, standing in front of her dress shop in Chicago, smiling, but with sadness behind her eyes.

Mama was successful, respected in the community, had friends, and a good life, Patricia continued.

But there was always something missing.

She never went back to Mississippi.

Not once.

Never talked about her family.

I didn’t even know I had relatives down here until she was dying.

What did she tell you then? Mrs.

Washington asked gently from the back seat.

Not much.

She was in hospice, in and out of consciousness.

But one afternoon, she grabbed my hand and said, “Patricia, I left people behind.

I had to run and I never could go back.

Find them.

Tell them I made it.

Tell them the delivery was successful.

” I didn’t understand what she meant.

They drove through the flat delta landscape and Patricia stared out the window at the cotton fields and small towns, trying to connect this place to the mother she’d known.

When they reached Holmes County and the small museum, Patricia stood for a long moment outside, composing herself before entering.

Inside, Mrs.

Washington had prepared a display of everything they’d found, the original photograph of young Ruby with flowers, the church records, the census documents, and the article about her dress shop.

Patricia approached the photograph of her mother as a child, and began to cry silently.

“She was so young,” she whispered.

“Just a baby.

How did she survive alone?” James gave her time, understanding that this was more than a historical discovery.

It was a daughter connecting with a part of her mother’s life that had been deliberately hidden to protect them both.

When Patricia had composed herself, she opened the bag she’d been carrying.

Mama kept a box under her bed.

I found it when we were clearing out her apartment after she died.

I looked through it, but didn’t understand most of what was there.

Now, I think I’m beginning to.

She pulled out a small metal box, the kind that might have held jewelry or important papers.

Inside were several items.

A pressed flower, dried and fragile after 90 years.

A small piece of cloth with a floral pattern and a folded piece of paper, yellowed and delicate.

The flower and cloth are from the dress she was wearing that day, Patricia explained.

Mama told me once that she kept a piece of every dress she ever made because she wanted to remember who she’d been before she learned to sew.

I never understood that until now.

Mrs.

Washington carefully lifted the pressed flower.

A blackeyed Susan, the same type Ruby had been holding in the photograph.

But it was the folded paper that made James’ breath catch.

He recognized it immediately from his enhanced analysis of the original photograph.

Is that he began? Patricia nodded.

The paper from the picture, the one she was hiding in the flowers.

Mama kept it her whole life.

With trembling hands, Mrs.

Washington unfolded the paper on the table.

The ink was faded, but still legible.

A list of names paired with numbers and biblical references that would have meant nothing to anyone outside the land trust network.

This is it, Mrs.

Washington breathed.

The actual paper she was carrying, the list that saved five families land claims.

Dr.

Mitchell, do you realize what we’re looking at? James was already photographing the document carefully, understanding its historical significance.

This is direct evidence of organized resistance to Jim Crow land theft.

This is proof that black communities fought back systematically, not just through individual acts, but through coordinated networks.

But Patricia was focused on something else.

She pointed to the bottom of the paper where someone had written in different shakier handwriting, “Esther an I made it to St.

Louis.

I hope you’re safe.

I will come back someday.

You’re Ruby.

” 1929.

She did try to send word, Patricia said, her voice breaking.

She didn’t just abandon her grandmother.

She tried to let her know she was alive.

Mrs.

Washington studied the note, then shook her head sadly.

It never reached Esther.

This paper stayed with Ruby, which means she never found a way to safely send it.

The risks were too great.

Any letter to Holmes County would have been intercepted and traced back to her.

The three of them sat in silence, feeling the weight of the tragedy.

Ruby and Esther, separated by fear and violence, both living for decades with unanswered questions and unresolved grief.

But there was also something else in that moment, a sense of completion.

Through this gathering of evidence, these connections across generations, Ruby’s story was finally being told.

Her courage was being recognized, and the delivery she’d risked everything for had succeeded not just in 1923, but continued to resonate a century later.

“There’s one more thing,” Patricia said quietly.

She reached into the box and pulled out a small notebook similar to the one Mrs.

Washington’s grandmother had kept.

Mama started writing her story near the end of her life.

She never finished it, but what’s here explains a lot about what happened after she left Mississippi.

She handed the notebook to James.

I want this story told properly, Dr.

Mitchell.

I want people to know what Mama did, what her generation did.

I want the land trust remembered.

Can you do that? James looked at the notebook, then at the photograph of young Ruby, then at Patricia’s hopeful face.

Yes, he said.

I can do that.

I will do that.

Six months later, James stood in the auditorium of the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson, watching as nearly 200 people filed in for the special exhibition opening.

The walls were covered with enlarged photographs, documents, and timelines telling the story of the Land Trust Network and Ruby Anne’s role in it.

Patricia Fletcher Williams sat in the front row next to Mrs.

Washington.

Both women dressed elegantly for the occasion.

Around them sat descendants of the five families whose land purchases Ruby had protected in 1923.

the Williams, Johnson, Roberts, Turner, and Cole families.

Through James’ research, he located relatives of each family and invited them to attend.

The exhibition was titled Hidden in Plain Sight: Child Messengers of the Land Trust Network, 1919, 1925.

It documented not just Ruby’s story, but the stories of at least 12 other children who had served as messengers for the network, carrying coded information, warnings, and documents that helped black families resist economic oppression during Jim Crow.

James had spent months working with Mrs.

Washington, Patricia, and other community historians to piece together the full scope of the network.

They discovered that the land trust had helped secure property rights for over 80 families across three counties, preserving wealth and stability that would benefit generations.

Many of those families still own the land today.

Some had kept it within the family for a century, while others had sold it, but used the proceeds to invest in businesses or education for their children.

The economic impact of the land trust’s work rippled forward through decades, creating opportunities that would have been impossible without the foundation of land ownership.

As James began his presentation, he started with the photograph that had begun everything.

Young Rubanne standing in front of her grandmother’s house holding flowers, smiling her quiet smile of determination.

What you’re looking at, James told the audience, is not just a photograph.

It’s documentation of an act of courage.

Hidden in those flowers is a piece of paper containing information that could have gotten this 10-year-old girl killed.

And she knew it.

But she carried it anyway because she understood that her community’s future depended on what she did that day.

He walked them through Ruby’s journey, her confrontation with the clan, her flight north, her decades of exile, her success in Chicago, and her inability to ever return home.

He showed them Ruby’s notebook, her written testimony about the fear, loneliness, and determination that had marked her early years.

But he also showed them the victory.

The land purchases had succeeded.

The families had prospered.

And while Ruby had paid a terrible price for her courage, her sacrifice had not been in vain.

When the presentation ended, James invited the descendants of the five families to come forward and share their stories.

One by one, they testified to how their families had held onto their land through the depression, through World War II, through the civil rights movement, and into the present day.

A woman in her 80s named Grace Williams spoke about how her grandfather’s farm purchased through the land trust in 1923 had allowed her father to pay for her college education in the 1950s.

She had become a teacher and her children had become doctors, lawyers, and professors.

A man named Marcus Cole, great great grandson of Reverend Cole, who had led the land trust, described how his family’s land had been sold in 1998 for development, providing enough money to establish a scholarship fund that had sent 43 young people from Holmes County to college.

Each story was a testament to the compound effect of Ruby’s courage in the land trust’s work.

After the formal program ended, Patricia approached the display where her mother’s photograph hung in a place of honor.

She touched the glass gently and turned to address the crowd that had gathered around her.

“My mother never talked about being a hero,” Patricia said, her voice steady and clear.

“She just said she did what needed to be done.

But I want you all to know something that she wrote in that notebook Dr.

Mitchell showed you.

” Near the end, when she was sick and knew she was dying, Mama wrote, “I always wondered if running away meant I was a coward.

Now I know that sometimes survival is its own form of resistance.

I lived.

I built something.

I raised a daughter who never had to be afraid the way I was afraid.

That was my second delivery.

Passing forward the freedom those families bought with their courage.

And my grandmother taught me with her love.

There wasn’t a dry eye in the room.

” Mrs.

Washington stood and embraced Patricia, then turned to address everyone.

Rubenne’s story is not unique.

All across the South during Jim Crow, there were networks like the Land Trust.

And there were brave people, often children, who risked everything to help their communities resist oppression.

Most of those stories were never recorded because the people involved were too afraid to speak.

And then they died before anyone thought to ask,” she gestured to the exhibition around them.

“But now we’re asking.

Now we’re listening.

And we’re discovering that resistance was everywhere, even when it looked like submission.

We’re learning that our ancestors were not just victims of oppression, but active agents fighting for their freedom and dignity, using whatever tools they had available, even if those tools were just flowers and a folded piece of paper.

As the evening wound down, James found himself standing alone in front of Ruby’s photograph.

He thought about that moment in the Mississippi Historical Society archives when he’d first noticed the hidden paper in her hands.

He’d been looking for a simple historical curiosity, but instead he’d found a story that challenged everything.

He thought he knew about resistance, courage, and the ways ordinary people fight for justice.

Ruby Anne had been 10 years old, the same age as his own daughter.

He tried to imagine his daughter making the choices Ruby had made, bearing the weight Ruby had carried, surviving what Ruby had survived.

He couldn’t.

But then again, Ruby probably couldn’t have imagined it either until the moment came when she had no choice.

That James realized was the real lesson of Ruby’s story.

Courage isn’t something you have or don’t have.

It’s something that emerges when circumstances demand it.

When the people you love need you to be brave, when the only alternative to action is unbearable.

Ruby Anne had been just a girl with flowers.

But she’d also been a messenger, a survivor, a builder, and a warrior.

She’d carried a secret that could have killed her, saved families she barely knew, and built a life from nothing after losing everything.

And now, a 100 years later, her story would finally be told.

The photograph would no longer show just a girl with flowers.

It would show a hero who had been hiding in plain sight all along, waiting for someone to look closely enough to see what she’d been holding in her hands.

Not just a piece of paper, but the future of her community.

News

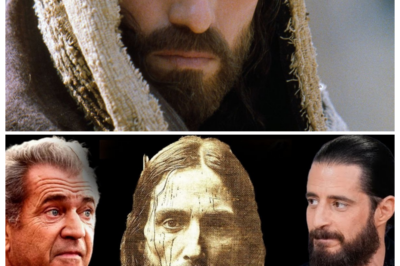

🎭 “I CARRIED THE CROSS OFF CAMERA TOO” — JIM CAVIEZEL FINALLY BREAKS HIS SILENCE ABOUT THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST AND REVEALS THE PAIN THAT NEVER STOPPED 🔥 In a trembling confession years after the cameras stopped rolling, Caviezel describes lightning strikes, broken bones, and eerie accidents that shadowed the set, hinting the suffering didn’t end with “cut,” but followed him home like a curse, leaving him wondering whether the role changed his soul forever 👇

The Silent Echoes of Truth In the dimly lit room, Jim Caviezel sat alone, shadows dancing across the walls. The…

🔥 “THEY DIDN’T WANT YOU TO READ IT” — MEL GIBSON CLAIMS THE ETHIOPIAN BIBLE WAS ‘BANNED’ AFTER CHURCH LEADERS DISCOVERED PASSAGES TOO POWERFUL TO CONTROL 📜 In a tense, late-night interview, Gibson alleges ancient texts hidden for centuries contain forbidden prophecies, missing books, and teachings that challenge everything modern Christianity was built on, warning that once believers see what was removed, “faith will never look the same again” 👇

The Forbidden Pages of Faith In the shadowy corridors of history, where whispers of the past linger like ghosts, Mel…

⚰️ MEL GIBSON STUNNED SILENT AS LAZARUS’ TOMB IS FINALLY OPENED — WHAT ARCHAEOLOGISTS FOUND INSIDE LEFT THE CREW TREMBLING 💥 Cameras roll as stone is moved for the first time in centuries, dust rising like smoke, and Gibson reportedly freezes mid-step, staring into the darkness as whispers spread that what lies inside doesn’t match anything historians expected, turning a biblical legend into a chilling, heart-pounding discovery that feels more like prophecy than history 👇

The Tomb of Secrets: A Hollywood Revelation The Unveiling of Lazarus: A Revelation That Shook the World In the heart…

🩸 JONATHAN ROUMIE & MEL GIBSON BREAK DOWN IN TEARS OVER THE SHROUD OF TURIN — HOLY RELIC SPARKS RAW CONFESSIONS AND SHOCKING REVELATIONS 💥 What began as a calm discussion turns into an emotional storm as the two stars speak with trembling voices about faith, doubt, and the weight of portraying Christ, their words hanging heavy in the air like incense, leaving viewers stunned as Hollywood meets holiness in a moment that feels less like an interview and more like a reckoning 👇

The Veil of Secrets In the dim light of a forgotten chapel, Jonathan Roumie stood before the ancient relic, the…

🩸 MEL GIBSON BLASTS THE VATICAN — “THEY’RE LYING TO YOU ABOUT THE SHROUD OF TURIN!” — HOLY RELIC ROW ERUPTS INTO GLOBAL FIRESTORM 🔥 Cameras barely start rolling before Gibson leans in, voice shaking with fury, claiming centuries of “carefully managed truth” and hinting that what believers were shown isn’t the whole story, sending historians scrambling, priests bristling, and millions wondering if the world’s most sacred cloth hides secrets too explosive for daylight 👇

The Shroud of Secrets Mel Gibson stood at the edge of a precipice, the weight of centuries pressing down on…

🕊️ POPE LEO JUST REVEALED THE TRUTH ABOUT THE 3RD SECRET OF FATIMA — MILLIONS STUNNED AS VATICAN FALLS INTO SILENCE AND BELLS STOP MID-CHIME 💥 What was supposed to be a quiet theological address turns into a jaw-dropping moment of history as the pontiff allegedly unveils details long whispered about for decades, cardinals freeze in their seats, cameras shake, and believers clutch their rosaries as if the sky itself just cracked open 👇

The Shattering Revelation of Pope Leo XIV In a world where faith often intertwines with doubt, the name Pope Leo…

End of content

No more pages to load