A Girl Smiles in 1895 — But Her Clenched Fist Holds a Hidden Truth

Dr.Sarah Mitchell adjusted her glasses as the afternoon light filtered through the tall archive windows in Louisville.

The Kentucky Historical Society had just acquired a collection of Dgerara types from an estate sale in Harlem County, and Sarah had volunteered to catalog them.

It was tedious work, but she loved it.

The quiet intimacy of examining faces from another century, imagining their lives, their joys, their sorrows.

Most of the photographs were typical for the era.

Stiff families in their Sunday best, stern patriarchs with thick mustaches, holloweyed women who’d borne too many children, boys and girls forced to hold perfectly still for long exposures, their expressions frozen somewhere between boredom and terror.

Then she saw it.

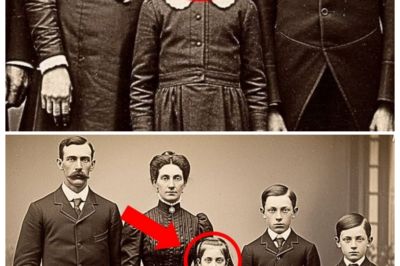

The photograph was dated March 1895, taken in front of a modest wooden house with a sagging porch and narrow windows.

A family of four stood in a neat line.

A broad-shouldered man with a thick mustache and cold eyes.

A thin woman whose face seemed carved from worry.

a teenage boy with his hands clasped rigidly behind his back and a girl who couldn’t have been more than 10 years old.

But it was the girl who made Sarah pause.

Unlike everyone else in the frame, she was smiling, a wide, almost radiant smile that seemed completely out of place among the solemn, unsmiling faces surrounding her.

Her dress was plain calico, patched carefully at the elbows, and her dark hair hung in two simple braids tied with fraying ribbon.

Her feet were bare despite the early spring chill that Sarah could almost feel emanating from the photograph.

But it was her right hand that caught Sarah’s attention.

Pressed firmly against her stomach, it was clenched into a tight fist, knuckles white, fingers curled with obvious tension.

Sarah leaned closer, her breath fogging the protective glass.

The longer she stared, the stranger it became.

Why was this child smiling when no one else was? And what was she holding so tightly that her small hand had formed a fist? She pulled out her magnifying glass and examined the hand more carefully.

There was definitely something there.

A slight bulge between the fingers, a hint of something metallic catching the weak sunlight, barely visible, but unmistakably present.

Sarah’s breath caught in her throat.

She had spent 15 years studying 19th century photographs, documenting families and communities, and she knew instinctively when something didn’t fit, when something was wrong.

She grabbed her notebook and began to write, her hand moving quickly across the page as questions flooded her mind.

Sarah spent the next morning at the county clerk’s office, surrounded by dusty ledgers and property records that hadn’t been digitized yet.

The photograph had been labeled only with a year and the vague designation Harland County, but the house itself was distinctive enough.

Two stories with weathered clabbered siding, narrow windows with shutters hanging at odd angles, and a stone chimney that leaned slightly to the left, as if the whole structure were slowly surrendering to gravity.

After 3 hours of cross-referencing old tax maps, land deeds, and property transfers, she finally found it.

A homestead on Pineville Road owned in 1895 by a man named Thomas Carver.

The deed showed he’d purchased the property in 1889 for $300, a modest sum, even for that era.

The name stirred something in her memory.

She opened her laptop and searched the historical society’s digital archives.

Thomas Carver had been a merchant of some local standing, moderately successful, known throughout the region for buying up land from struggling families during the brutal economic depression of the 1890s.

He’d accumulated nearly 200 acres before his death in 1904, and the property had passed to his son, who’d sold most of it off during the First World War, but there was no mention anywhere of a daughter.

Sarah frowned and kept digging, her eyes burning from reading faded handwriting.

Birth records, church registries, census logs.

She searched them all methodically.

Finally, buried in the 1895 county census, she found it.

Carver household.

Thomas, age 41, merchant.

Ida, age 38, housewife.

James, age 15, labor.

Clara, age nine, orphan, taken in 1893, an orphan.

Sarah’s pulse quickened.

Clara wasn’t their daughter by birth.

She’d been taken into the household 2 years before the photograph was made.

But from where and why, and most importantly, what had happened to her biological parents? She jotted down the name, Clara, and stared at the photograph again, now displayed on her laptop screen.

That brilliant smile, that desperately clenched fist.

The contrast between the two was jarring, almost painful to witness.

What had happened to this girl? What secret was she holding? And why did the family around her look so grim while she alone smiled? Sarah grabbed her coat.

Harland County was a 4-hour drive through winding mountain roads, but she had to see that house.

She had to walk the ground Clara had walked.

She had to know.

The road to Pineville twisted through dense forests of oak and pine, following creek beds and climbing steep bridges that revealed breathtaking valleys below.

Sarah’s car rattled over loose gravel as she passed.

Abandoned coal mines with rusted equipment still visible, weathered barns with sagging roofs and small family cemeteries tucked into hillsides.

Their stones tilted and covered in lykan.

When she finally found the house, her heart sank.

It was still standing, but only just.

The porch had collapsed entirely, leaving splintered boards jutting up like broken teeth.

The windows were boarded up with plywood that had itself begun to rot, and kudzu vines crawled up the walls like grasping green fingers, slowly pulling the structure back into the earth.

A rusted no trespassing sign swung from a single nail on what remained of the front door.

Sarah parked on the overgrown driveway and stepped out into the thick humidity.

Cicas droned in the trees, their sound rising and falling in hypnotic waves.

The air smelled of honeysuckle and decay.

She approached the house cautiously, her camera hanging around her neck, documenting everything.

The windows on the ground floor were too high and too thoroughly boarded to see through.

But as she circled the property, stepping carefully over fallen branches and rusted farm equipment, she noticed something.

A small cemetery plot about 50 yards behind the house, enclosed by a low iron fence that had mostly survived the years.

The gate hung open, hinges red with rust.

She pushed through and stepped inside, her shoes sinking slightly into the soft earth.

There were four headstones arranged in a neat row.

The first three were easier to read, their inscriptions still clear despite years of weather.

Thomas Carver Squint Nqueter A Carver 1856 1910 James Carver 1880 1952.

The fourth was smaller, set slightly apart from the others, as if even in death Clara had been kept separate.

Sarah knelt in the damp grass and carefully brushed away the accumulated dirt and moss.

The inscription was faint, the letters worn, almost smooth by more than a century of rain and wind, but she could just make it out.

Clara, 1886, 1895.

Beloved child.

Sarah’s stomach turned.

Clara had died in 1895, the same year the photograph was taken.

She’d been only 9 years old, but the word beloved felt wrong, a hollow, a lie carved in stone.

Sarah took several photographs of the grave, then stood slowly and looked back toward the ruined house.

Its empty windows like blind eyes staring back at her.

Something terrible had happened here.

She could feel it in her bones.

Sarah returned to town and stopped at the Harland County Public Library, a small brick building on Main Street that doubled as a community center and local history museum.

The librarian, a woman in her 70s with silver hair pulled back in a neat bun and sharp intelligent eyes behind wire rimmed glasses, looked up from her desk as Sarah entered.

the bell above the door jingling softly.

“Help you find something?” she asked, her accent thick with the musical lltilt of Appalachia.

“I’m researching a family that lived here in the 1890s,” Sarah said, approaching the desk and carefully setting down the photograph she’d printed.

“The Carvers, Thomas and I, a Carver.

Do you know anything about them?” The woman’s expression shifted just slightly, a tightening around her eyes, a subtle downward turn of her mouth, but it was enough for Sarah to notice.

She set down her pen and picked up the photograph, studying it with the careful attention of someone who understood the weight of history.

Thomas Carver, she said slowly, her voice measured.

I’ve heard the name.

My grandmother used to talk about him when I was a girl.

Said he was a hard man, ambitious, not well-liked, but respected in the way that wealthy men are respected even when they shouldn’t be.

What about the girl? Sarah pointed to Clara to that inongous smile and clenched fist.

She was an orphan according to the census taken in by the family in 1893.

The woman’s gaze lingered on Clara’s face, and something like sadness flickered across her features.

“There were rumors,” she said quietly, glancing toward the empty library, as if afraid someone might overhear about how some families treated the children they took in back then.

“Orphans didn’t have legal rights.

” “No protection.

” “They were useful, if you understand my meaning.

” Sarah felt a chill despite the warm afternoon.

“Useful how?” “Labor,” the woman said bluntly, meeting Sarah’s eyes.

“Farm work, housework, anything that needed doing.

” They weren’t adopted out of Christian charity or love.

They were free hands, extra workers who couldn’t complain or leave or demand wages.

Some families treated them decently enough.

Others, she trailed off, shaking her head.

Sarah’s mind raced.

She thought again of Clara’s smile, so bright and so wrong, and her clenched fist holding something precious or dangerous or both.

“Is there anyone still alive who might remember that time?” Sarah asked, leaning forward.

“Anyone who might have known the carvers or heard stories about them?” The woman hesitated, clearly weighing something in her mind that nodded slowly.

There’s a man, Henry Pike.

He’s 93 now.

Lives in the Maplewood Care Home just outside town.

His grandmother was a midwife here in the 1890s.

Delivered most of the babies in three counties.

She kept detailed journals of her work and the family she served.

Henry donated most of them to the historical society years ago, but he might still have some, and his memory is still sharp.

Sarah’s heart leapt with hope.

Can you give me his address? The woman wrote it down on a scrap of paper.

Tell him Ruth sent you,” she said.

“And tell him.

Tell him it’s about remembering the ones who were forgotten.

” Henry Pike sat in a wheelchair by the window of his room at Maplewood.

A patchwork quilt his granddaughter had made draped over his lap.

Afternoon sunlight streamed through the glass, illuminating dust moes that drifted lazily through the air.

His eyes were cloudy with cataracts, but his mind was remarkably sharp, his voice rough, but steady as he greeted Sarah.

when she explained why she’d come, showing him the photograph and telling him about Clara’s grave and the questions that had been building in her mind.

He nodded slowly, his weathered hands trembling slightly as he took the picture.

“My grandmother, Eliza,” he said, staring at Clara’s face.

As she delivered half the babies in this county between 1875 and 1920, saw things, knew things.

People trusted her with their secrets, their fears, their shame.

She understood that her work wasn’t just about bringing children into the world.

It was about bearing witness.

Did she ever mention the carvers? Sarah asked, pulling a chair closer and sitting down.

Henry’s jaw tightened, the muscles working beneath his papery skin.

She did, not fondly, not kindly.

He wheeled himself over to a small wooden chest in the corner of the room, its surface scarred with age and use.

With effort, he opened it and pulled out a leatherbound journal, its pages yellowed and brittle.

The binding cracked.

He handled it with the reverence it deserved, and handed it carefully to Sarah.

“She wrote about a girl,” he said, his voice dropping almost to a whisper.

an orphan living with the Carvers.

I remember reading about her years ago when I first went through grandmother’s journals.

Broke my heart then.

Still does.

Sarah carefully opened the journal, mindful of its fragility.

The handwriting was cramped and faded, written in the careful script of someone educated but pragmatic.

She flipped through the pages slowly until she found an entry dated February 18th, 1895.

Called to the Carver home today for the girl, Clara, she had a fever and a terrible cough.

Mrs.

Carver said she’d been working outside in the cold rain without proper clothing, fetching water from the creek because the well had run dry.

The child is thin as a willow branch, her hands raw and cracked from scrubbing floors and doing laundry and cold water.

I asked if she was being fed enough.

Mrs.

Carver did not answer.

Thomas stood in the doorway the entire time I was there watching his presence filling the room like a threat.

I do not trust that man.

There is something cold in him, something calculating.

I fear for this child.

Sarah’s hands trembled as she turned the page, her heart pounding.

Another entry dated March 10th, 1895.

Saw Clara in town today near the general store.

She was carrying two heavy buckets of water, her shoulders bent under the weight.

When she saw me, she smiled, such a bright, unexpected smile that it startled me.

I gave her a biscuit I’d been saving.

She took it and immediately hid it in her dress pocket, glancing around as if afraid it would be taken from her.

She thanked me in a whisper and hurried away.

I fear deeply for this child.

There’s something wrong in that house.

Sarah looked up at Henry, her throat tight.

“What happened to her?” “She died,” Henry said quietly, his cloudy eyes distant with memory.

“Just a few weeks after that last entry grandmother made.

” March 28th, 1895.

They said it was pneumonia given to the county physician as cause of death recorded in the church registry, and she was buried in the family plot.

But Sarah heard the doubt in his voice.

The unspoken questions.

“You don’t believe it was pneumonia?” Sarah said it wasn’t a question.

Henry was silent for a long moment, staring out the window at the mountains in the distance.

“I don’t know what I believe,” he finally said.

“But I know my grandmother didn’t believe it.

” She wrote one more entry after Clara died.

“Would you like to read it?” Sarah nodded, unable to speak.

Henry reached over and turned the pages for her, stopping at an entry dated March 30th, 1895.

The handwriting was different here, shakier, more emotional.

Clara is dead.

They say pneumonia, but I do not believe it.

I examined her body when they sent for me to prepare her for burial.

There were no signs of the fluid in the lungs that accompanies pneumonia.

Her body bore marks, bruises, old and new.

This child was not loved.

She was not cherished.

And now she is gone, and no one will ask questions because she was only an orphan, and orphans do not matter to people like the Carvers.

May God forgive us all for our silence.

Sarah closed the journal carefully, her hands shaking.

She looked at Henry, tears burning in her eyes.

No one investigated.

No one cared enough to, Henry said simply.

That’s how it was then.

That’s how it’s always been for children who don’t matter to the right people.

But Sarah was already thinking ahead.

Clara had mattered.

She had mattered enough to hide something in her clenched fist.

Something important enough to hold on to even when being photographed, even when surrounded by the people who had failed her.

“Thank you,” Sarah said, standing.

“Uh, thank you for sharing this with me.

” “Find out what happened to her,” Henry said as she turned to leave.

“Give her the voice she never had,” Sarah nodded.

“I will.

” Back in her hotel room that night, Sarah spread everything out on the desk.

The photograph, copies of the census records, notes from her conversations, and photographs of Clara’s grave.

She made herself a cup of coffee and sat down, studying the photograph under the harsh light of the desk lamp.

She pulled out her high-powered magnifying lens, the kind used by art historians and document examiners, and focused it on Clara’s clenched fist.

With the increased magnification, the object hidden between her fingers became clearer, definitely metallic, definitely ovalshaped with what appeared to be decorative edging around the perimeter.

A brooch.

Clara was holding a brooch.

Sarah’s mind raced through possibilities.

Why would a poor orphan girl dressed in patched calico and bare feet possess a brooch? Such items were luxury goods made of silver or gold, often containing precious stones or enamel work.

They were heirlooms passed down through families, symbols of status and affection.

So, where had Clara gotten it? And more importantly, why hide it? Why clutch it so tightly that her knuckles went white, even while being forced to smile for a photograph? Sarah opened her laptop and began searching historical records again.

This time, focusing on 1893, the year Clara had been taken in by the Carvers.

She combed through newspaper archives, death notices, court records, anything that might explain where an orphan girl had come from.

After two hours of searching, her eyes burning with fatigue.

She found it buried in the back pages of the Harlland County Gazette.

Dated November 16th, 1893.

Local woman found dead.

Foul play suspected.

Mrs.

Rebecca Frost, age 28, was discovered deceased in her home on Mil Creek Road on the evening of November 14th.

The body was found by a neighbor who had not seen Mrs.

Frost for several days.

Authorities report signs of violent struggle within the home.

Her young daughter, believed to be approximately 7 years of age, is missing.

Sheriff Morton has stated that an investigation is ongoing and asks anyone with information to come forward immediately.

Sarah’s heart pounded as she scrolled to the next edition.

Dated November 30th, 1893.

Orphan child recovered.

Taken in by local family.

The daughter of the late Mrs.

Rebecca Frost has been located and placed with the family of Mr.

Thomas Carver of Pineville Road, who has graciously agreed to provide for the child’s welfare and upbringing.

Sheriff Morton has stated that the investigation into Mrs.

Frost’s death continues, though no suspects have been identified.

The child, who has been deeply traumatized by recent events, is reported to be recovering under the care of the Carver family.

Sarah sat back, her blood running cold.

Clara was Rebecca Frost’s daughter, and Rebecca Frost had been murdered violently in her own home just weeks before Clara was placed with the Carvers.

But the newspaper said the investigation was ongoing.

What had happened? Had anyone been arrested? Had anyone been held accountable? She searched for follow-up articles, but found nothing.

The story had simply disappeared from the public record, as if Rebecca Frost’s murder had never mattered.

As if it had been quietly forgotten by everyone except perhaps the one person who couldn’t forget, her daughter.

Sarah grabbed her phone and called the Kentucky Historical Society’s research desk.

“I need everything you have on Rebecca Frost,” she said, her voice urgent.

“Death records, property records, anything.

And Thomas Carver, every document, every mention.

I need it all, and I need it now.

” Because Sarah understood something now.

something that made her chest ache with rage and sorrow.

Clara hadn’t just been holding a brooch in that photograph.

She’d been holding her mother’s brooch.

And possibly, probably she’d been holding the only piece of evidence that could prove who had killed Rebecca Frost.

The only piece of evidence that could point to the man who had taken her in, not out of kindness, but to keep her silent.

The documents arrived by courier the next morning, filling two large archive boxes.

Sarah spread them across the hotel room’s bed and began the painstaking work of piecing together the truth.

property deeds, tax records, court filings, personal correspondence, the paper trail of two lives that had intersected with deadly consequences.

Rebecca Frost had been a widow, left with a small but valuable plot of land, 35 acres with creek access and good timber after her husband, William Frost, died in a mining accident in 1891.

According to the documents, she’d managed the property herself for two years, selling timber rights to maintain a modest but independent living.

Court records showed she’d successfully defended the property against a claim from a distant relative of her late husband in 1892.

But what caught Sarah’s attention were the letters, copies of correspondence preserved in the county clerk’s files as part of various legal proceedings.

Starting in early 1893, Thomas Carver had written to Rebecca Frost repeatedly, making increasingly generous offers to purchase her land.

The letters were polite but persistent, each one emphasizing how difficult it must be for a woman alone to manage such property, how he could offer her a fair price and security.

Rebecca had refused every offer.

In her responses, formal, carefully worded letters written in an educated hand, she made it clear that the land was her daughter’s inheritance, that she intended to hold it until Clara came of age, and that no amount of money would persuade her to sell.

The final letter from Thomas Carver was dated October 15th, 1893, less than a month before Rebecca was found dead.

The tone had shifted from persuasive to threatening, though the threat was veiled in concern.

I must urge you to reconsider.

Mrs.

Frost, a woman and child alone are vulnerable to many dangers in these isolated hills.

It would be a tragedy if something were to happen that could have been prevented through more prudent decision-making.

Sarah’s hands clenched around the paper.

It wasn’t quite an explicit threat, nothing that could be used in court, but the implication was clear enough.

3 weeks later, Rebecca Frost was dead.

And according to property records filed in January 1894, her 35 acres had been transferred to Thomas Carver.

The deed listed the transaction as settlement of debts with no price indicated.

Processed through the county probate court as part of Rebecca Frost’s estate settlement, but Rebecca had no debts.

The document showed she’d been current on her taxes, had no outstanding loans, owed nothing to any merchant or bank.

Sarah pulled out another document, the probate record itself.

It was prefuncter, processed quickly with minimal review.

The presiding judge had been a man named Howard Langley, who, according to other documents Sarah found, had been a business partner of Thomas Carver in several land speculation ventures.

The corruption was there, woven through every document, every transaction.

Rebecca Frost had been murdered for her land.

Her daughter had been taken in by her mother’s killer.

not as an act of charity, but as a way to legitimize the theft, to appear benevolent, while ensuring that any potential witness to his crime remained under his control and influence.

But Clara had known.

Somehow, even as a seven-year-old child, she had understood what had happened.

And she had held on to something, her mother’s brooch, as evidence, as memory, as the one thing that connected her to the truth.

Sarah looked at the photograph again, at Clara’s smile that was really a mask, at her clenched fist that was really an act of defiance and preservation.

She thought of that little girl living for two years in the house of the man who had murdered her mother.

Forced to call him a benefactor, unable to speak, unable to accuse, unable to escape until she died at 9 years old.

Her secrets buried with her.

Or were they? Sarah drove to the old Presbyterian church on the southern edge of Harland County, a white clapped building with a tall steeple that had been converted into a community center in the 1970s when the congregation had dwindled and merged with another church.

But the original records, births, deaths, marriages, when pastoral correspondents dating back to 1875 were still stored in the basement, carefully preserved by volunteers who understood their historical importance.

The current volunteer archivist was a retired school teacher named Ruth Anne, a small woman with bright eyes and steady hands who took her work seriously.

When Sarah explained what she was looking for, Ruth Anne nodded thoughtfully and led her down the narrow stairs into the basement.

We’ve got everything organized by year, she said, pulling on the chain of a bare light bulb that illuminated rows of metal filing cabinets.

The church correspondence is filed separately from the registries.

What year are you looking for? 1895, Sarah said.

March, specifically.

Ruth Anne moved to a cabinet marked 1890 to 1900 and pulled open a drawer.

Inside were folders organized by month and year, each one carefully labeled in neat handwriting.

She pulled out one marked March 1895 and handed it to Sarah.

You can work at that table there, she said, pointing to a scarred wooden table beneath the single bulb.

Just handle everything carefully and let me know if you need anything.

Sarah sat down and opened the folder with trembling hands.

Inside were pastoral letters, reports to the church council, records of home visits to sick parishioners, and correspondence with other churches in the region.

She worked through them methodically, reading each one, looking for any mention of Clara or the Carver family.

And then she found it 3/4 of the way through the stack.

A letter dated March 15, 1895, written in the careful hand of Reverend Samuel Holt.

It had never been sent.

Instead, it appeared to have been filed away.

Perhaps as a record of the reverend’s concerns, perhaps as insurance, perhaps as testimony he hoped would never be needed.

Sarah’s hands shook as she read, “To whom it may concern.

I write this with a heavy and troubled heart, praying that I am wrong in my suspicions, but fearing that I am not.

” Yesterday, March 14th, a child in my congregation came to me in secret, waiting until the church was empty before approaching me in the vestri.

This child, Clara, the orphan girl residing with the Carver family, was frightened, trembling, and spoke of things no child should know or carry.

She told me that her mother did not die by accident or by the hand of some unknown intruder.

She claimed to know who killed her mother, though she did not speak the name aloud.

When I pressed her gently to tell me who, she simply looked at me with eyes far too old for her young face and said, “He took everything.

He took Mama and then he took me.

” She showed me a brooch, a small silver piece with a blue stone that she said had been her mother’s most precious possession.

She opened it before me, and inside was hidden a folded piece of paper, a letter, she said, that her mother had written in the days before her death.

She would not let me read it, but she told me it contained the truth, that it named the man who threatened her mother and took their land.

I urged her to give the letter to the sheriff to let me accompany her and help her speak.

But she is afraid, terrified in fact, and I cannot say her fear is unfounded.

She believes, perhaps rightly, that no one will listen to an orphan child, especially one beholdened to a man of Mr.

Carver’s standing in influence in this community.

She fears that speaking out will only bring harm to herself, and she may well be correct.

I have prayed long through the night for guidance.

I have promised Clara that I will keep her secret until she is ready to speak.

But I fear for her safety.

I fear that the man who would kill a woman for her land would not hesitate to silence a child who threatens to expose him.

If anything should happen to this child, if she should fall ill, if she should meet with any accident, if she should die under circumstances that seemed too convenient, let this letter serve as testimony.

Let it be known that she came to me, that she told me she knew the truth about her mother’s death, and that she feared the man who now claims to care for her.

May God forgive me if my silence leads to harm.

May God grant me wisdom to know what is right.

Reverend Samuel Hol, Pineville Presbyterian Church.

Sarah sat in stunned silence, the letter trembling in her hands.

Clara had tried.

She had tried to speak, tried to expose the truth.

She had gone to the one person who might help her, who might believe her.

And Reverend Hol had wanted to help.

She could feel his anguish and uncertainty in every line of the letter.

But he hadn’t acted.

Whether from fear, from uncertainty about what a child’s testimony could accomplish, or from the social realities of a world where men like Thomas Carver were believed over orphan children, he had waited, had prayed, had written this letter as insurance, and two weeks later, Sarah checked the church registry that Ruth Anne brought her at her request.

Clara was dead.

The entry was brief.

March 28th, 1895, Clara, age 9, caused pneumonia.

Buried March 30th, family plot, Carver property.

Reverend Holt had made one final entry in the margin in smaller, more cramped handwriting, as if he’d added it later.

“May God forgive us for what we failed to prevent.

” Sarah carefully photographed the letter and the registry entry.

She thanked Ruth Anne and walked out of the church into the late afternoon sunlight, her mind racing.

Clara had the evidence.

She’d been holding it in that photograph, literally holding it in her clenched fist, her mother’s brooch with her mother’s letter hidden inside.

The letter that named Thomas Carver.

But where was it now? Clara had died, been buried.

Had the brooch been buried with her or had someone taken it? Sarah pulled out her phone and started making calls.

She needed to find that brooch because if it still existed, if that letter could still be found after more than 130 years, then Clara could finally speak.

The truth could finally be heard and justice, however delayed, might finally be served.

Sarah returned to Louisville and spent the next week working 18-hour days, compiling everything she’d discovered into a comprehensive report.

The photograph that had started it all.

Eliza’s journal entries documenting Clara’s mistreatment.

The property records showing the theft of Rebecca Frost’s land.

The newspaper articles about Rebecca’s murder and the investigation that had gone nowhere.

The letters between Rebecca and Thomas Carver.

Reverend Holt’s testimony of Clara’s secret visit.

The suspicious death certificate listing pneumonia as the cause when a midwife had documented otherwise.

She wrote it all out methodically, building a case across time, showing pattern and motive and opportunity.

She submitted it to the Kentucky Historical Society with a formal recommendation that Clara’s death be reopened as a historical investigation and that Rebecca Frost’s murder be re-examined in light of new evidence.

Within days, the story had been picked up by the Louisville Courier Journal.

Then the Lexington Herald Leader, then regional news outlets across Kentucky and Tennessee.

The photograph of Clara, that heartbreaking image of a smiling child with a clenched fist, became the focal point of discussions about historical justice, about children who had no voice, about crimes that had been buried under respectability in time.

The story went viral on social media.

Historians, genealogologists, true crime enthusiasts, and advocates for children’s rights all shared it, each adding their own research and commentary.

Someone created a crowdfunding campaign to restore Clara’s grave.

It reached its goal in three hours.

And then came the breakthrough Sarah had been hoping for.

A woman named Patricia from Lexington sent an email to the historical society.

Her grandmother had been an antiques dealer in Harland County in the 1950s, and among her estate items was a collection of jewelry purchased from various estate sales over the years.

Patricia had inherited the collection and had been slowly cataloging it.

One piece was a small silver brooch with a blue stone oval-shaped Victorian era with delicate filigree work around the edge.

According to her grandmother’s records, it had been purchased at an estate sale in 1952 when the last of the Carver property was being liquidated after James Carver’s death.

Patricia had seen the viral story.

She wondered if this could be Clara’s brooch.

Sarah drove to Lexington the next day, her heart pounding the entire drive.

Patricia met her at her home, a gracious older woman who understood the weight of what she might possess.

She brought out the brooch in a small velvet box.

The moment Sarah saw it, she knew.

It matched the description perfectly.

The size, the shape, the blue stone that caught the light.

And when Patricia carefully opened the brooch’s back clasp, revealing a small hidden compartment Sarah’s breath caught.

Inside, folded so many times it was barely larger than a postage stamp, was a piece of paper, yellowed and fragile with age.

With shaking hands and Patricia’s permission, Sarah carefully unfolded it under the light.

The handwriting was faded but legible, written in the same educated hand as Rebecca Frost’s letters in the county records, March 1893.

If anything happens to me, let it be known Thomas Carver has threatened me repeatedly.

He wants my land and will not accept my refusal.

He came to my home again today and said that women who don’t listen to reason often meet with accidents.

He said my daughter would be better off with a proper family who understands reality.

I am afraid.

I am alone, but I will not sell.

This land is Clara’s inheritance, and I will protect it with my life if necessary.

If I am found dead, look to Thomas Carver.

He is not what he seems.

He is not a good man.

Clara, if you’re reading this, know that I loved you more than anything in this world.

Fight for what is yours.

Fight for the truth.

Your mother, Rebecca, Sarah’s vision blurred with tears.

This was it.

The evidence Clara had protected with everything she had.

The truth her mother had written knowing she might die.

the accusation that had been hidden for 132 years.

Waiting.

Patricia insisted that the brooch and letter be donated immediately to the Kentucky Historical Society.

Within hours, a team of archivists and forensic document experts confirmed its authenticity.

The paper was consistent with 1890s stock.

The ink matched the period, and most importantly, the handwriting was definitively Rebecca Frost’s, matching perfectly with her known correspondence in the county records.

The story exploded across national news.

Major networks picked it up.

The New York Times ran a front page feature.

Documentary filmmakers reached out.

But more importantly, it sparked a broader conversation about historical accountability, about the crimes that had been hidden behind respectability, about the children who had been silenced.

The Kentucky Historical Society convened a special panel of historians, legal scholars, and genealogologists to examine the case thoroughly.

While Thomas Carver could not be prosecuted, he’d been dead for 120 years.

The panel issued a formal historical finding that Thomas Carver had, by the preponderance of evidence, murdered Rebecca Frost to acquire her property, that he had taken in her daughter to silence potential testimony and legitimize his theft, and that Clara had died under suspicious circumstances while in his care, likely killed to prevent her from ever speaking the truth she carried.

The finding was published, distributed to libraries and historical societies across the state, and entered into the permanent record.

Thomas Carver’s name, once associated with prosperity and civic leadership, was now forever linked to murder, theft, and the death of a child.

Rebecca Frost’s land, the 35 acres that had cost two lives, was traced through property records.

It had been subdivided and sold many times over the decades.

The current owners, when they learned the history, agreed to allow a memorial to be placed on the property.

A simple stone marker was erected near the creek bearing the names of Rebecca and Clara Frost and the words, “Murdered for refusing to surrender.

” remembered for refusing to forget that Clara’s grave was completely restored.

The small, lonely headstone was replaced with a larger monument of polished granite.

The new inscription read, “Clara Frost, 1886, 1895, daughter of Rebecca Frost.

She held the truth when no one else would listen.

She protected her mother’s words until they could finally be heard.

Her silence was never surrender.

It was survival, her voice, though delayed, has now spoken.

” The dedication ceremony was attended by hundreds of people, historians, advocates, descendants of other families who had lost land in similar circumstances and children from local schools who had learned Clara’s story.

Sarah stood beside the grave as a pastor offered a prayer in a children’s choir sang.

When it was Sarah’s turn to speak, she looked at the faces gathered around her and then down at the photograph she held.

The one that had started everything.

Clara smiling her defiant smile, her fist clenched around her mother’s truth.

Clara was 9 years old when she died,” Sarah said, her voice carrying across the quiet cemetery.

She lived only two years with the man who murdered her mother.

Two years of knowing the truth, of carrying it, of being unable to speak it without risking everything.

She went to her pastor, hoping he would help her.

He wanted to, but he was afraid.

We were all afraid throughout history to stand up for children who had no power, no protection, no voice.

She paused, looking at the restored grave, but Clara never let go.

In that photograph, surrounded by the people who had taken everything from her, she smiled, not because she was happy, but because she was strong, and she held on to that brooch, her mother’s brooch, containing her mother’s words, even when it meant she couldn’t relax.

Couldn’t let her guard down for even the moment it took to capture that image.

Sarah’s voice grew stronger.

Story isn’t just about the past.

It’s about now.

It’s about every child who knows something is wrong, but doesn’t know how to speak.

It’s about listening when children tell us they’re afraid.

It’s about believing them when they say someone has hurt them.

It’s about creating a world where a 9-year-old girl doesn’t have to hold on to evidence alone, where she doesn’t have to choose between silence and danger.

She held up the photograph.

This image traveled through 132 years to reach us.

Clara waited all that time for someone to see what she was really saying.

Not just with her smile, but with her fist.

She was saying, “I remember.

I know.

And someday you’ll know, too.

” The crowd was silent, except for the sound of people weeping quietly.

“Today we finally hear her,” Sarah concluded.

Today, Clara Frost speaks and we will make sure her voice is never forgotten again.

6 months after the dedication ceremony, the photograph hangs in a place of honor at the Kentucky Historical Society in Frankfurt, behind museum grade glass with carefully controlled lighting to preserve it for future generations.

The exhibit is called Hidden Truths: Children’s Voices in American History.

And Clara’s photograph is the centerpiece, surrounded by context.

Copies of the documents Sarah uncovered, reproductions of Rebecca’s letters, the brooch itself displayed in a secure case beside it, and the text of the letter that had been hidden inside for so long.

Visitors stopped to look at it every day.

School groups come on field trips.

Teachers use Clara’s story in their curriculum when discussing reconstruction era America, the treatment of orphans, women’s property rights, and the long struggle for justice.

Clara has become more than a victim.

She’s become a symbol of resilience, of the power of truth to survive, even when those who carry it cannot.

Sarah visits the exhibit often.

She’s written a book about Clara’s story titled The Clenched Fist: How One Photograph revealed a 132year-old murder.

It became a bestseller and sparked renewed interest in other cold historical cases, inspiring a new generation of researchers to look more carefully at the forgotten, the marginalized, the silenced voices in archived photographs and documents.

But more than the book, more than the recognition her work has received.

Sarah treasures the letters she gets from people who have seen the exhibit or read Clara’s story.

Letters from adoptive families who’ve been moved to learn more about their children’s histories.

Letters from social workers and child advocates who’ve put Clara’s photograph in their offices as a reminder of why their work matters.

Letters from survivors of childhood abuse who found strength in knowing that truth, however delayed, can still emerge and be acknowledged.

One letter came from a teacher in Harlem County who had taken her entire fifth grade class to see Clara’s grave.

The students had each written a letter to Clara telling her they were sorry for what happened to her, that they would remember her, that they would try to be the kind of people who listen to children who need help.

The letters were placed in a waterproof box and buried near the memorial stone, a time capsule of compassion reaching back across the centuries.

Today, Sarah stands in front of the exhibit once more, watching as a young girl, maybe eight or nine years old, about Clara’s age, stares intently at the photograph.

The girl’s mother stands beside her, reading theformational placard aloud in a quiet voice.

When they finish, the girl doesn’t move.

She keeps staring at Clara’s face, at that smile, at that clenched fist.

Finally, she looks up at her mother and asks, “Did it hurt?” “Holding on that tight for so long.

” The mother considers the question seriously.

“Probably,” she says gently.

“But sometimes holding on is the bravest thing we can do.

” The girl nods slowly, then reaches out and touches the glass with her small hand, her fingers spread over Clara’s image.

“I’m glad someone finally listened to you,” she whispers.

Sarah’s throat tightens with emotion.

“This is why the work matters.

This is why uncovering the past is never just about history.

It’s about connection, about recognition, about making sure that suffering is acknowledged and remembered so that perhaps incrementally the world can become a place where such suffering happens less often.

She thinks about the journey that began with a single photograph in a dusty archive, about following the threat of curiosity and outrage until it unraveled a story that had been deliberately buried.

About Clara, who at 9 years old had more courage than most adults, who had understood that some truths are worth protecting even when protection costs everything.

The photograph no longer fills Sarah with sadness, though the sorrow is still there, embedded in every pixel of that image.

Now it fills her with something else, a fierce kind of pride.

Pride in Clara’s strength.

Pride in Eliza, the midwife, who documented what she saw, even when she couldn’t prevent it.

Pride in Reverend Hol, who wrote his letter even though he was afraid.

Pride in all the people who had preserved these fragments, the photograph, the journals, the letters, the brooch, not knowing that someday someone would assemble them into truth.

Clara’s smile is no longer a mystery to Sarah.

It’s not happiness, not innocence, not the simple joy of childhood.

It’s defiance.

It’s determination.

It’s a 9-year-old girl’s way of saying, “You can take everything else, but you cannot take this.

You cannot make me forget.

You cannot silence the truth I carry.

” And her clenched fist, that small hand holding so tightly to her mother’s brooch, to her mother’s words, to her mother’s love, is no longer just a detail in a photograph.

It’s a declaration.

It’s resistance.

It’s hope.

Because Clara had known something that her killers had not understood, that truth is patient.

That evidence, carefully protected, can wait.

That a photograph taken to show a respectable family accepting an orphan out of Christian charity could, if examined closely enough by someone who cared, reveal something entirely different.

Could reveal a captive.

Could reveal resistance.

Could reveal a crime.

The young girl and her mother move on to the next exhibit, but Sarah stays looking at Clara’s face at those eyes that had seen too much.

at that smile that was really a mask.

At that fist that had held on through everything.

“You did it,” Sarah whispers to the photograph.

To the girl who has been dead for 130 years, but who is somehow more alive now than ever.

“You held on long enough.

Your mother’s words reached us.

Your truth reached us.

We heard you, Clara.

Finally, we heard you.

” And in the controlled lighting of the museum, with the afternoon sun streaming through distant windows, Clara’s photograph seems almost to glow.

That smile, once so mysterious and troubling, now reads differently to Sarah.

Not as tragedy alone, but as triumph, because Clara had won.

She had protected her mother’s truth through two years of fear and oppression.

She had kept the evidence safe, even when she couldn’t use it herself.

She had held on, literally and figuratively, until her hands went white, until her body gave out, until death claimed her, but death hadn’t claimed her story.

Death hadn’t claimed her courage.

Death hadn’t claimed the truth she protected.

Those had survived.

Those had waited.

Those had been patient.

And now, 132 years after a little girl smiled for a photograph while clutching her murdered mother’s accusation in her small, determined fist, the world finally knew.

Thomas Carver had taken Rebecca Frost’s life and land.

He had taken Clara’s childhood and ultimately her life as well.

He had believed that he could bury the truth as easily as he’ buried his victims.

But he had underestimated the power of a mother’s words and a daughter’s love.

He had underestimated the courage of a nine-year-old girl who refused to let go.

He had underestimated the persistence of truth.

And in the end, across more than a century of silence Clara Frost had spoken.

Her voice, once silenced by violence and fear and death itself, now echoes in museums and classrooms and books and hearts.

Her story, once buried and forgotten, is now taught and remembered and honored.

She’s no longer the forgotten orphan girl who died alone and afraid.

She is Clara Frost, daughter of Rebecca, keeper of truth, holder of justice, and her clenched fist frozen forever in that 1895 photograph is no longer a mystery.

It is a promise kept.

News

Historians Restored This 1903 Portrait — Then Noticed Something Hidden in the Man’s Glove Emma Brooks adjusted her computer screen, squinting at the sepia toned photograph that had arrived at the Pennsylvania Historical Society three days earlier. The image showed a family of five standing in a modest garden, their faces frozen in the stern expressions common to early 20th century portraits. The father stood at the center, one hand resting on his wife’s shoulder, the other hanging stiffly at his side. Three children flanked them, the youngest barely tall enough to reach her mother’s waist. The photograph had been donated by Katherine Miller, an elderly woman from Pittsburgh who claimed it showed her great-grandparents. Emma had seen hundreds of similar images during her 15 years as a photographic historian. But something about this one nagged at her. Perhaps it was the quality of the original print, remarkably well preserved despite its age, or the intensity in the father’s eyes that seemed to pierce through more than a century of distance.

Historians Restored This 1903 Portrait — Then Noticed Something Hidden in the Man’s Glove Emma Brooks adjusted her computer screen,…

Why Did Historians Become Pale When Enlarging the Face of the Younger Girl in This 1891 Image? The Haunting Revelation of the 1891 Portrait In the dim light of the archive room, Dr. Eleanor Hayes meticulously examined the faded photograph, its edges curling with age. The image depicted a young girl, her face innocent yet enigmatic, captured in a moment that transcended time. But as Eleanor enlarged the photograph, a chill ran down her spine. The girl’s eyes, once merely a reflection of childhood, now seemed to harbor secrets that could unravel history itself. Eleanor had dedicated her life to understanding the past, but this image was different. It was as if the girl was staring into her soul, demanding to be heard. The historians had warned her about this particular photograph, claiming it was cursed, a relic that had brought misfortune to those who dared to delve too deep. But Eleanor, driven by an insatiable curiosity, pressed on. As she zoomed in, the girl’s face transformed. The smile that once appeared sweet now twisted into something sinister.

Why Did Historians Become Pale When Enlarging the Face of the Younger Girl in This 1891 Image? The Haunting Revelation…

This 1901 studio portrait looks normal — until experts zoomed in on the child’s eyes Dr.Sarah Brennan’s hands trembled slightly as she adjusted the highresolution scanner over the faded photograph. The basement archive of the Boston Heritage Museum was cold, smelling of old paper and preservation chemicals. She had been cataloging donated Victorian photographs for 3 weeks now, and most had been unremarkable. Stiff portraits of forgotten families, their stories lost to time. This one seemed no different at first glance. A studio portrait dated 1901, stamped on the back with the name Whitmore Photography Studio, Lawrence, Massachusetts. A well-dressed couple stood rigid, the man’s hand on his wife’s shoulder. Between them sat a small girl, perhaps 6 years old, in a white-laced dress with ribbons in her dark hair. The child’s hands were folded neatly in her lap, holding a small bouquet of white liies. Sarah began the scanning process, watching as the digital image appeared on her computer screen in extraordinary detail.

This 1901 studio portrait looks normal — until experts zoomed in on the child’s eyes Dr.Sarah Brennan’s hands trembled slightly…

🚨 Greg Biffle’s last flight revealed in 60 seconds as a countdown compresses terror into heartbeats, timelines snap shut, and every routine check feels fateful while the sky turns witness to courage, pressure, and a moment that refuses to stay silent ✈️⏱️ the narrator slices time with a razor voice, hinting that when seconds decide legends, the truth doesn’t shout—it clicks, pops, and dares you to keep watching 👇

The Final Descent In the heart of the night, the engines roared like a beast awakened from slumber, echoing through…

🤖 Salvaging & restoring the giant Robot Batman abandoned at the bottom of the ocean turns into a gothic rescue opera as divers descend into ink-black pressure, find a rusted vigilante staring back, and spark a clash between nostalgia and nightmare when cables tighten and the legend refuses to stay buried 🦇🌊 the narrator growls that this isn’t scrap recovery, it’s an exhumation of myth, where every bolt screams history, every bubble carries regret, and the sea seems angry about losing its darkest trophy 👇

Echoes from the Abyss: The Resurrection of the Forgotten Titan In the depths of the ocean, where light dares not…

End of content

No more pages to load