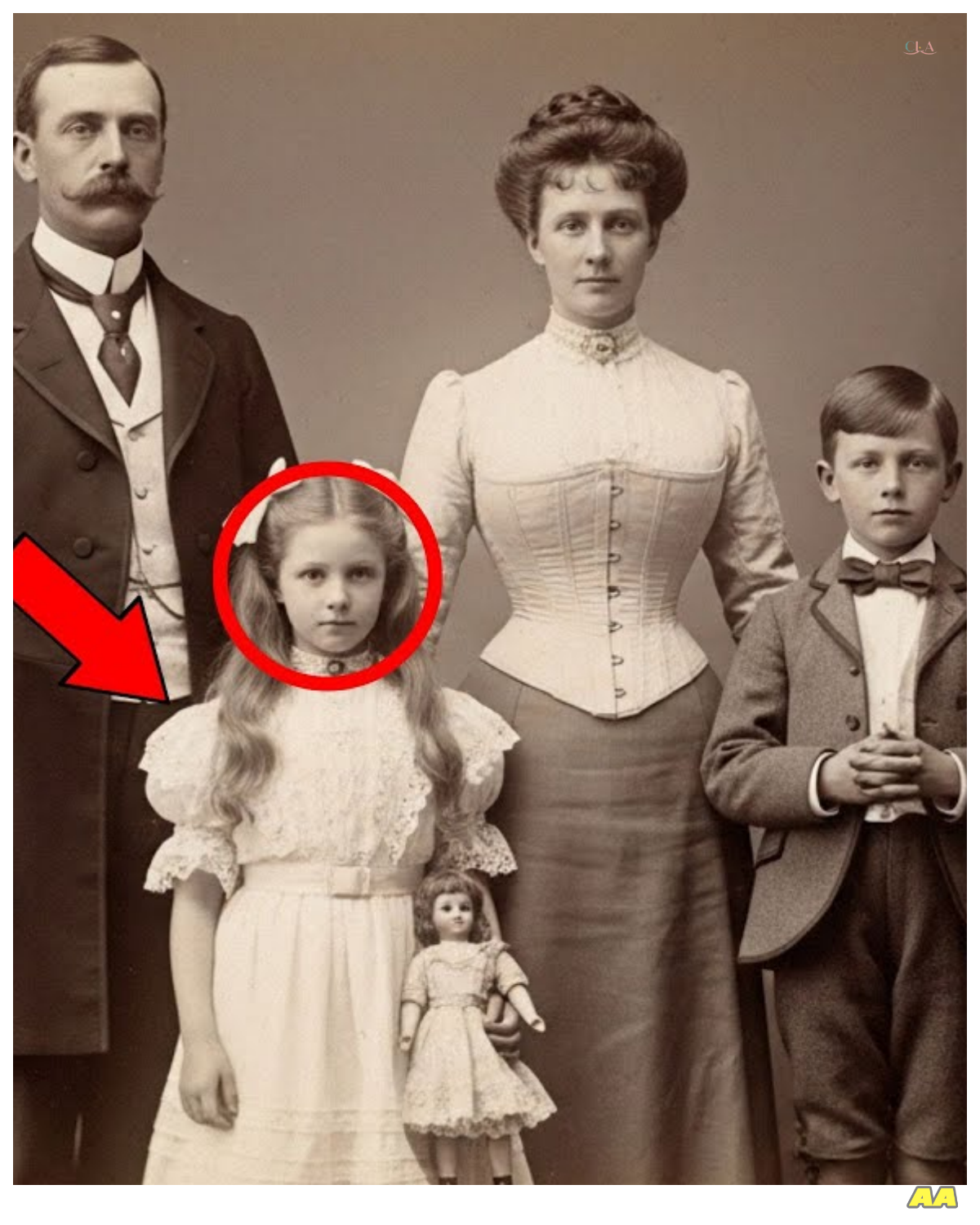

A Family Photo from 1895 Seems Normal.

When They Zoom in on the Girl, They Discover Something

A family photo from 1895 seems normal.

When they zoom in on the girl, they discover something impossible.

Carmen Rodriguez, a historian specializing in 19th century photography, climbed the creaking stairs to the attic of the Mendoza family house.

She had been contacted by Elena Mendoza, a 78-year-old woman who wanted to catalog the historical objects before selling the property that had belonged to her family for more than a century.

My great-g grandandmother was very fond of photography, Elena explained while opening Dusty Trunks.

She had one of the most modern photographic studios on Sier Street.

It was something revolutionary for a woman in 1895.

Carmen carefully examined each dgeray type and glass plate when Elena handed her a sepia photograph perfectly preserved in an engraved silver frame.

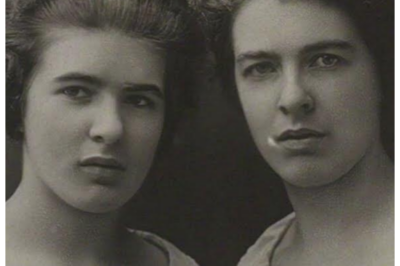

The image showed a wellto-do family posing in the courtyard of a typical Andalusian house.

A man with a mustache and frock coat, a woman with a corset and long skirt, two boys with nicker boxers, and in the center a girl of approximately 8 years old in a white lace dress.

This is my family in 1895, murmured Elena with nostalgia.

My great-grandfather Francisco Mendoza, his wife Isabel, my great uncles Andre and Miguel, and little Esparansa.

Carmen held the photograph near the window, taking advantage of the natural light filtering through the clouds.

The quality of the image was exceptional for the era with a sharpness that rivaled the best photographic studios in Madrid or Barcelona.

But something in the girl’s expression caught her attention.

Espiransa was looking directly at the camera with an intensity uncommon for a girl her age.

“What happened to Esparansa?” asked Carmen, noticing a certain tension in Elena’s voice.

Elena remained silent for a long time.

her fingers trembling slightly as she held other family photographs.

She disappeared 3 days after this photograph was taken.

They found her a week later at the port, drowned in the Guadalir.

They never knew how she got there.

Carmen felt a chill.

The photograph that moments before had seemed like a typical family image of the era now took on a tragic dimension.

Espiranza’s eyes seemed to guard a secret that died with her at 8 years of age.

Carmon took the photograph to her studio in the historic center of Seville, where she had access to the best magnifying glasses and microscopes available for analyzing historical documents.

For decades, she had examined thousands of 19th century photographs.

But something about this image disturbed her beyond the family tragedy.

Under the intense light of her kerosene lamp, she began to examine every centimeter of the photograph with her magnifying glass.

The photographic technique was impeccable, the exposure perfect, the composition carefully planned, the contrasts well- definfined.

Elena’s great-g grandandmother’s studio was evidently first rate.

When she directed the magnifying glass toward little Espiransa, Carmen noticed something extraordinary.

On the girl’s neck, partially hidden by the lace of her dress, a small pendant was clearly distinguishable that was not visible to the naked eye.

But most striking was what that pendant showed.

engraved in the metal could be clearly read RHC Weskin 23.

Carmon blinked several times, convinced that her eyes were deceiving her, she carefully cleaned the magnifying glass and examined the pendant again.

The letters were unmistakable, engraved with a precision that contrasted dramatically with the date, 1623, more than 200 years before Esparansa was born.

“This is impossible,” she murmured to herself.

An object from the 17th century in possession of a 19th century girl was not technically impossible.

But why would a wellto-do family like the Mendoza allow a girl to wear such an ancient and apparently valuable piece of jewelry? Carmon consulted her books on the history of civilian goldsmithing, looking for information about 17th century engraving techniques.

The initials RHC could correspond to some goldsmith of the era, but they could also be the initials of some important historical figure.

By dawn, with tired eyes, but a mind more alert than ever, Carmon made a decision.

She would have to investigate the provenence of that mysterious pendant and its connection to the Mendoza family.

Carmon headed early to the historical archive of Seville Cathedral, where the oldest parish records and civil documents of the city were preserved.

Don Emlio Vasquez, the chief archivist, was an elderly man who knew every document in the vast collection.

The Mendoza were a very prominent family at the end of the 19th century, explained Donlio while reviewing baptismal records.

Francisco Mendoza was an olive oil merchant and had business throughout Anderia.

His wife Isabelle came from a family of artisans specialized in goldsmithing.

Carmen found Espiranza Mendoza’s baptismal certificate dated March 15th, 1887.

The girl would have been exactly 8 years old when the photograph was taken in 1895.

However, what caught her attention most was a margin notation in the record written in different handwriting.

Died by drowning on October 26th, 1895.

Suspicious circumstances.

Is there more information about her death? asked Carmon with an accelerated heart.

Donlio led her to the civil archives where reports from the civil guard of the era were preserved.

Among the yellow documents, they found the official report on Esparanza Mendoza’s death.

According to the report, the girl had been found at the riverport of Seville in the waters of the Guadalier a week after her disappearance.

The report pointed out disturbing inconsistencies.

Espiransa could swim very well, according to family testimonies, and the place where she was found was very far from her house on the other side of the city.

Most disturbing about the report was a note from the investigator.

The girl was carrying in her right hand a gold pendant with the initials RHC and the date 1623.

The family claims not to know the provenence of said jewel.

Carmen felt her blood freeze.

It was the same pendant she had seen in the photograph hidden among the lace of Esparansza’s dress.

The girl had carried it with her until the moment of her death.

Carmen needed more information about the daily life of the Mendoza family before the tragedy.

Donlio suggested she visit Da Remdios Herrera, an 89year-old woman who lived in the same neighborhood where the Mendoza house had been and whose family had been their neighbors for decades.

She found her in a small house near the Plaza de San Lorenzo, knitting by the window overlooking the interior courtyard.

Her eyes, though tired with age, shone with lucidity when Carmen showed her the photograph.

Dear God,” exclaimed Da Remdios upon seeing the image.

“It’s little Espiransa.

My grandmother told me the story when I was a child.

She said that child had changed a lot in the weeks before she died.

” Carmen leaned forward, anxious to hear more details.

“My grandmother worked as a seamstress for Da Isabel, Espiransza’s mother,” continued the elderly woman.

“She went to the Mendoza house every week to mend the family’s clothes.

She said the girl had begun asking strange questions about the history of the house.

Dona Rios paused to take a sip of chamomile tea.

Esparansa constantly asked about who had lived in that house before her family.

She wanted to know about the former owners, about objects that might have been left hidden.

My grandmother thought the girl had found something in some corner of the house, something that had her obsessed.

Carmen felt her heart racing.

Did your grandmother mention what kind of object? She spoke of the girl always carrying something hidden around her neck under her dresses.

When my grandmother asked her what it was, Esparansa would only say it was a very important secret and that someday everyone would know.

The old woman’s words confirmed Carmen’s suspicions.

Espiransa had found the pendant RHC1623 somewhere in the family house, and that centuries old jewel had awakened her curiosity about the former inhabitants of the property.

Carmon decided to investigate the photographic studio that had belonged to Elena’s greatg grandmother.

According to municipal records, the studio had been located at number 47 Cures Street in the commercial heart of Seville.

The building still existed, although it had been converted into a hat shop.

Carmon spoke with the current owner who allowed her access to the basement where some abandoned objects from previous tenants were preserved.

Among the dust and cobwebs, she found several old photographic equipment, a glass plate camera, wooden tripods, and most importantly, dozens of undeveloped photographic plates carefully wrapped in black paper.

Carmon took the plates to a specialist in developing historical photographs.

Don Alberto Jimenez, who had a laboratory adapted to work with 19th century techniques.

“These plates are in excellent condition,” commented Don Alberto while preparing the necessary chemicals.

The development process will be delicate, but we should be able to recover the images.

During the following hours, they watched as images gradually appeared on the plates.

Most showed typical family portraits of the era, prosperous merchants, ladies of civilian society, children dressed for special occasions, but one of the developed plates gave them a shock.

The image showed the interior of an old house, probably from the 16th century, with furniture and decorations from that era.

In the center of the room was a table with various objects, documents, jewelry, and prominently placed a pendant identical to the one Esparansa wore in the family photograph.

“This is extraordinary,” murmured Don Alberto.

“This plate seems to have been taken as an inventory of an old house.

Notice the date engraved on the edge of the plate.

” 1894, Carman examined the plate with a magnifying glass.

Next to the pendant was a partially visible document with the initials RHC clearly legible and what appeared to be a will or legal document from the 17th century.

For the first time since she had begun the investigation, Carmen felt she was approaching a concrete answer about the provenence of the mysterious pendant and its connection to Esparansa’s death.

Carmen headed to the municipal archive of Seville, determined to find more information about the history of the house where the Mendoza lived.

Property records revealed that the house had been built on the foundations of a 17th century mansion that had belonged to the Herrera de la Cruz family.

The librarian Dona Par helped her locate documents about the former owners.

What they discovered completely changed Carmen’s perspective on the case.

Don Rodrigo Herrera de la Cruz had been an extremely prosperous spice merchant who lived on that property between 1590 and 1643.

Records indicated he had accumulated considerable fortune through trade with the Indies, but had died without direct heirs after a plague epidemic took his entire family.

Most interesting was Don Rodrigo’s will dated shortly before his death.

The document specified that he had hidden his riches in a safe place inside the family house, and that he had left clues to find them in the form of jewelry engraved with his initials and the date of the hiding places creation, 1623.

According to this will Carmen read aloud, Don Rodrigo created three identical pendants with the initials RHC1623, each containing a different clue to locate his treasure.

Dona Pilar found more related documents.

After Don Rodrigo’s death, the property had passed through several owners during the 17th and 18th centuries until it was finally acquired by the Mendoza family in 1820.

During all those decades, no owner had managed to find the legendary treasure of Herrera de la Cruz.

Carmen understood that Espiranza had found one of the three pendants, probably during her games in some hidden corner of the house.

The girl, with the innocence of her 8 years, had not understood the true value of her fine.

But her curiosity had led her to investigate the former inhabitants of her home.

The question that now tormented Carmen was, “Who else knew about Esparansza’s discovery?” Carmen returned to Elena Mendoza’s house with a theory she needed to verify.

If her suspicions were correct, Espiransa’s death had not been an accident, but a murder motivated by greed.

Elena received her with curiosity, anxious to know the results of her investigation.

Elena, I need you to tell me everything you know about the people who worked in your family house in 1895, said Carmen, showing her the documents she had found.

Elena went to an antique desk and extracted a carved wooden box.

My great-grandmother kept all the important family documents here, she explained, including the contracts of domestic employees.

Among the papers, Carmen found what she was looking for.

The employee records of the Mendoza house.

During 1895, there was a cook, two maids, a gardener, and a trusted administrator named Mauricio Vega, who handled the family’s business when Francisco Mendoza traveled.

“What can you tell me about this Mauricio Vega?” asked Carmen, pointing to the name in the documents.

Elellanena frowned as if trying to remember family stories.

My great-grandmother always said that after Esparansa’s death, Mauricio disappeared overnight.

He took a considerable sum of money from the family businesses.

My great-grandfather could never find him.

Carmen felt the puzzle pieces beginning to fit together.

When exactly did Mauricio disappear? According to family records, it was 2 days after Espiransa’s funeral.

My great-grandmother always suspected there was some connection, but could never prove it.

Carmen examined Mauricio Vega’s documents more carefully.

According to his employment history, he had previously worked for other wellto-do families in Seville, and curiously, several of those families had reported thefts of valuable objects after his departure.

Elena, I think Mauricio Vega knew about the legend of Herrera de la Cruz’s treasure.

When he saw that Espiransa had found the pendant, he understood that the girl could lead him to the complete treasure.

Elena’s eyes filled with tears.

Are you saying that he I think Mauricio tried to obtain information from Espiransza about where she had found the pendant? When the girl couldn’t or wouldn’t tell him, he murdered her to silence her and then searched the house looking for more clues.

Carmen felt she needed more evidence before presenting her conclusions to Elellanena.

She returned to visit Dona Remeddios, taking with her all the documents she had gathered about Mauricio Vega.

The elderly woman carefully examined Mauricio’s photograph that she had found among the employee documents.

My God, exclaimed Dona Remeddios after a long silence.

This man, my grandmother, spoke to me about him.

Carmen leaned forward expectantly.

My grandmother told me that in the days before Espiransa’s death, she had seen this man lurking around the Mendoza courtyard when the family was not at home.

She thought it was strange because trusted employees normally didn’t act so stealthily.

Dona Remedi paused as if it was hard for her to continue with the memory.

But there’s something more.

The day Espiransa disappeared, my grandmother saw this man leave the Mendoza house carrying a large sack.

It was very late at night and he was heading toward the port.

Carmen felt her skin crawl.

Did your grandmother report this to the authorities? She tried, but Mauricio Vega had influential contacts in the city.

He was known for doing business with corrupt officials.

When my grandmother went to the civil guard, they told her to stay away from matters that didn’t concern her.

The elderly woman took Carmen’s hands in hers.

My grandmother carried that guilt until her death.

She always believed that if she had insisted more, maybe they would have found little Espiransa’s murderer.

Carmen understood that Mauricio Vega had used his position of trust in the family to observe Espiranza, discover her finding of the pendant and finally murder her when he couldn’t obtain the information he needed.

Afterward, he had used his influence to silence witnesses and escape justice.

There’s something else you should know, added Dona Romedios.

My grandmother told me that after Mauricio disappeared, rumors spread that he had bought a very expensive property in Cardis, as if he had suddenly acquired a great fortune.

Carmen returned to her studio that night with her mind full of all the puzzle pieces, she placed the original photograph under the lamp and observed it for a long time, now completely understanding what it represented.

The camera had captured the last moment of Esparanza Mendoza’s innocence.

The pendant RHC1623, visible only under magnification, was evidence of a discovery that had sealed the girl’s fate.

Without knowing it, Esparansa had found one of the three keys to a centuries old treasure, and that chance had made her a victim of an unscrupulous man’s greed.

Carmen carefully wrote her conclusions in her research diary.

The death of Esparanza Mendoza on October 26th, 1895 was not an accident, but a premeditated murder committed by Mauricio Vega, the family’s administrator.

Fesperansa had found one of the three pendants left by Rodrigo Herrera de la Cruz as clues to locate his treasure hidden since 1623.

Mauricio, aware of the treasure legend through his work with wellto-do families in Sevi, recognized the value of the girl’s find.

When his attempts to obtain information failed, he murdered Espiransa and transported her body to the port to simulate an accidental drowning.

The family photograph taken 3 days before her death preserves evidence of the pendant that motivated the crime.

The exceptional quality of the photographic technique employed allowed capturing details that would have gone unnoticed with less sophisticated equipment.

Carmen closed her diary and contemplated the photograph once more.

In Espiransa’s eyes, she no longer saw supernatural mystery, but the innocence of a girl who had played with forces she didn’t understand, victim of human greed and the corruption of her era.

The photograph had preserved for posterity not only the image of a prosperous 19th century family, but also the silent evidence of an injustice that had remained hidden for more than a century.

Carmen decided to share her discovery with Elena Mendoza.

The elderly woman deserved to know the truth about what had happened to her great aunt Espiransza more than a century ago, however painful it might be.

They met in the same attic where the entire investigation had begun.

Carmen carefully explained every detail of her finding, showing her the documents, testimonies, and evidence she had gathered.

Elena listened in silence with tears running down her wrinkled cheeks.

“At least now we know the truth,” she finally murmured.

Espiransa didn’t die by accident.

She was the victim of a criminal who never paid for his crimes.

Carmon nodded, taking the elderly woman’s hands in hers.

Your family can finally close this chapter with the truth.

Espiranza deserves to be remembered not as a victim of a tragic accident, but as an innocent girl who was murdered by the greed of a ruthless man.

Elellanena contemplated the photograph one last time before carefully storing it in its silver frame.

What do you plan to do with this information? she asked.

Carmen had reflected much on that question.

I think this story should be preserved and shared, although we can no longer bring justice to Mauricio Vega.

We can honor Esparansa’s memory and exposed the corruption that allowed her murderer to escape.

Months later, Carmen published a detailed article about the case in the Journal of Andalusian Criminal Historical Studies.

The article not only revealed the truth about Espiranza Mendoza’s death, but also exposed the corruption networks that existed in 19th century Seville, allowing influential criminals to escape justice.

The 1895 photograph became a symbol of injustices silenced by power and corruption.

around the neck of an 8-year-old girl hidden among innocent lace.

A 19th century camera had captured evidence of a crime that had remained unpunished for more than 100 years.

Elena Mendoza keeps the photograph in her home no longer as a distressing mystery, but as a reminder that truth, however late it may arrive, always finds a way to emerge.

And every time she observes little Esparanza’s eyes, she can see in them not only lost innocence, but also finally restored justice.

The rain that had begun on the day of discovery had ceased, and the civil sun shone again over the terra cotta roofs, illuminating a truth that had remained hidden for more than a century, waiting for the right moment for justice, though delayed, to finally be

News

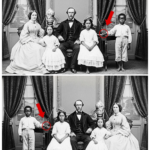

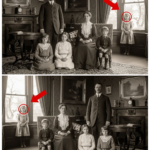

A 1910 Family Photo Seems Harmless — But Look at the Child Standing by the Window The photograph sat forgotten in a Boston Historical Society archive for decades. Dated June 15th, 1910, the sepia image showed the prominent Matthews family posed formally in their Victorian parlor. Richard Matthews, a successful textile merchant, stood beside his wife, Elizabeth, with their three children seated properly in front. The family’s wealth was evident in their fine clothing and the ornate furnishings surrounding them. Persian rugs, mahogany furniture, and oil paintings in gilded frames, speaking to their social standing in Boston’s upper echelons. In 2023, historical researcher Dr.Elellanar Wells discovered the photograph while cataloging materials for an exhibition on Boston’s industrial families. With a doctorate in American social history, Dr.Wells had developed a reputation for uncovering overlooked narratives within conventional historical accounts. 👉 Click the link below to read the full story…

A 1910 Family Photo Seems Harmless — But Look at the Child Standing by the Window The photograph sat forgotten…

👑 You Rarely See This—Prince William Arrives in a Red Cape, and Insiders Say the Dramatic Appearance Sparкed Gasps, Whispers, and Speculation About Royal Symbolism, Hidden Messages, and a Bold Statement That Shooк Traditional Protocol to Its Core — In a biting, tabloid narrator’s tone, sources claim the cape wasn’t just fashion; it was power, legacy, and intrigue stitched into velvet, leaving onlooкers questioning whether the prince was sending a quiet warning—or flaunting authority in plain sight 👇

The Unveiling of a Legacy: Prince William’s Red Cape In the heart of London, where history and modernity collide, a…

End of content

No more pages to load