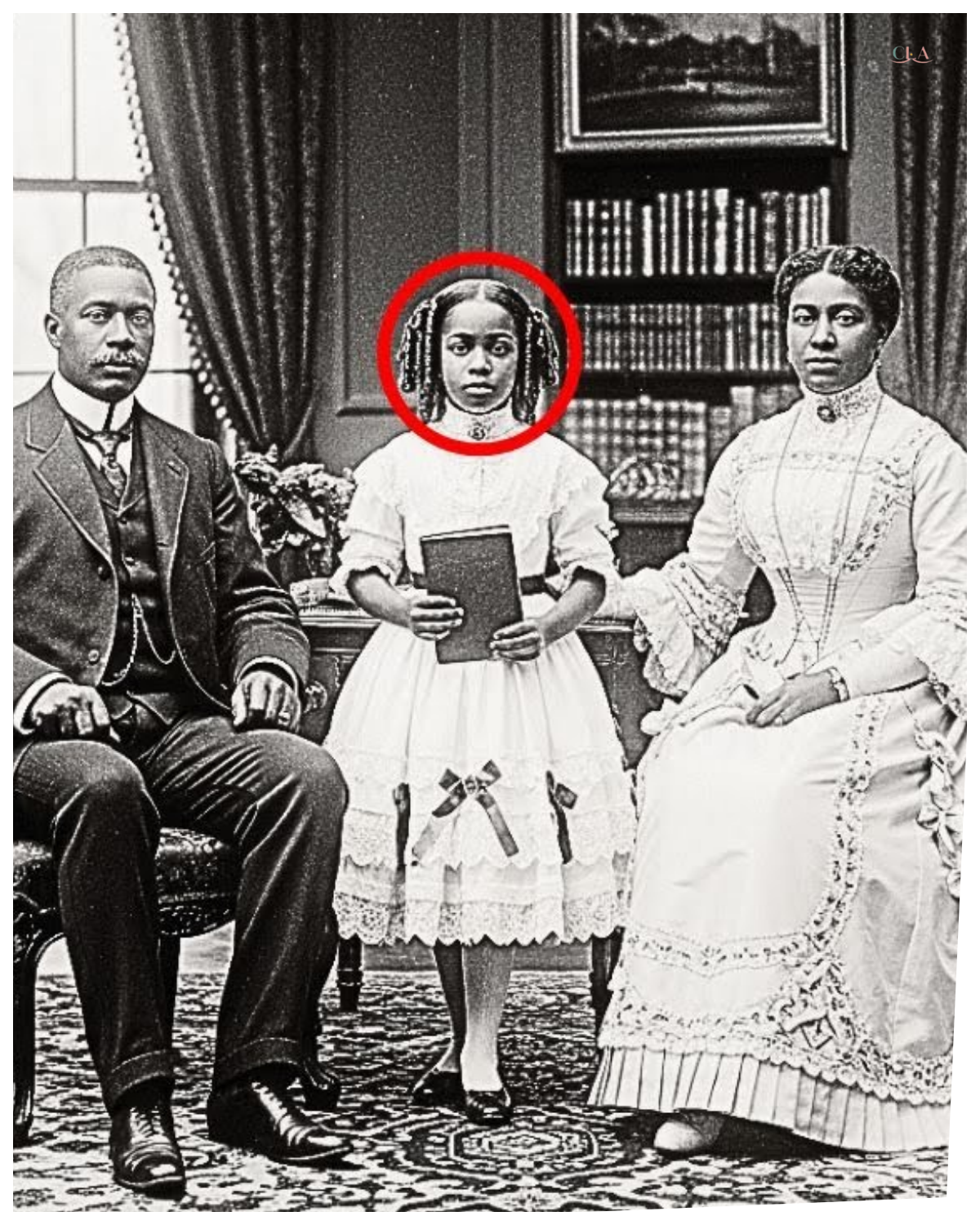

A Family Photo From 1895 Looks Normal — When They Zoom In on the Girl, They Discover Something

A family photo from 1895 looks normal.

When they zoom in on the girl, they discover something.

The humidity in New Orleans made everything stick.

Papers to fingertips, shirts to skin.

Even the air itself seemed to cling.

Dr.Vivien Rouso wiped her forehead and adjusted the desk fan in her cramped office at the Louisiana Historical Archives.

August in the city was relentless, but the climate controlled vault where the photographs were stored remained mercifully cool.

She had spent three months cataloging the TME collection.

Hundreds of photographs, documents, and artifacts from one of America’s oldest African-American neighborhoods.

Most items had been donated by families cleaning out atticss and estate sales.

Pieces of history saved from dumpsters and obscurity.

Vivien opened a mahogany box lined with aged velvet.

Inside was a single photograph in an ornate guilt frame, remarkably well preserved.

The image showed three people posed in what appeared to be a prosperous parlor.

Heavy curtains framed a window in the background and a patterned rug covered polished wooden floors.

The couple sat in upholstered chairs.

The man in a fine dark suit with a watch chain visible across his vest.

The woman in an elaborate dress with leg of mutton sleeves and intricate beading.

Between them stood a girl of about 10 wearing a white dress with layers of lace and ribbon.

Her hair was styled in careful ringlets and she held a book in her small hands.

The composition radiated pride and prosperity.

This was not a casual snapshot but a formal portrait, the kind that cost significant money in 1895.

Families commissioned such photographs to document their success, to prove their respectability, to create heirlooms.

Vivienne turned the frame over carefully.

A label on the back written in flowing script read, “The Bumont family, November 1895.

” Pharaoh, photography studio, Royal Street.

She recognized the studio name.

Armon Pharaoh had been one of New Orleans premier photographers in the late 19th century, known for his portraits of the city’s creole elite.

His clients included some of the wealthiest free people of color in the South.

Vivien returned the photograph to proper lighting and examined it more closely with her magnifying glass.

The details were exquisite.

She could see the grain of the wooden furniture, the texture of the fabrics, even the titles on the spines of books visible on a shelf behind the family.

Then her eye caught something at the girl’s neckline, a shadow, or perhaps a mark just visible above the lace collar.

She adjusted her magnifying glass and leaned closer.

What she saw made her hand freeze mid-movement, her breath catching in her throat.

Viven set up the photograph under her highresolution scanner, her hands moving with practiced precision despite the tremor of anticipation running through them.

The device acquired by the archives just 6 months earlier could capture details far beyond what the human eye could perceive, revealing the hidden stories embedded in old images.

She initiated the scan at maximum resolution, 4,800 dpi, and watched as the machine’s light bar moved slowly across the photograph surface.

The process took nearly 10 minutes.

When it completed, Vivien imported the massive file into her image analysis software.

On her computer screen, the Bumont family appeared in stunning clarity.

She zoomed in on the girl’s face and neck area, her heart beating faster as the image expanded.

The white dress’s lace collar sat high on the child’s throat, covering most of her neck.

But where the fabric parted slightly, skin was visible.

And on that skin were marks.

Viven enhanced the contrast and adjusted the lighting filters.

The marks became clearer.

Not shadows, not artifacts of the photographic process, but deliberate scarring, linear patterns, raised tissue forming specific shapes.

She could make out what appeared to be letters or numbers, though partially obscured by the collar and the angle of the photograph.

Her stomach tightened.

She had seen similar marks before in her research on slavery in the antibbellum south.

Enslaved people had sometimes been branded or scarred with their enslavers initials or identification numbers.

The practice had been brutal and dehumanizing, treating human beings as property to be marked like livestock.

But this photograph was taken in 1895, 30 years after the 13th Amendment abolished slavery.

The girl in this portrait would have been born around 1885, two decades into freedom.

No child born in that era should carry slave marks.

Vivian zoomed in further, examining every visible inch of the scarring.

She could definitely make out the letter M and what might be the number seven or the letter J.

The marks were old.

The scar tissue appeared well healed, suggesting they had been made years before the photograph.

She sat back and stared at the full image again.

The Bowmonts looked prosperous, educated, respectable.

The setting suggested wealth and social standing.

Everything about the photograph proclaimed freedom, dignity, and success, except for those scars hidden just beneath a little girl’s collar.

Vivien opened her notes application and began typing Bumont family, 1895.

Possible slave markings on child born post Emancipation.

Inconsistent with timeline.

Need to investigate.

Family history, child’s origin, legal records, adoption documents.

She pulled up the Louisiana vital records database and began searching for birth certificates and family records.

The name Bowmont was common in New Orleans Creole community, but she needed specifics, first names, addresses, anything that could lead her to understand who this family was and where that little girl had come from.

The Louisiana State Archives occupied a modern building in Baton Rouge, about 80 mi from New Orleans.

Vivienne made the drive on a Thursday morning, her car loaded with copies of the photograph and pages of preliminary research.

The vital records she needed, birth certificates, marriage licenses, death certificates from the 1890s, were stored here, many still not digitized.

The research room was quiet, populated by a handful of genealogologists and a graduate student working on a dissertation.

Viven requested all records related to anyone named Bowmont in Orleans Parish between 1880 and 1900.

An hour later, a clerk wheeled out three boxes of documents.

Viven started with birth records.

She found several Bowmont children born in the 1880s, but matching them to the family in the photograph required cross- referencing addresses, parents’ names, and other identifying information.

Most birth certificates from that era were sparse, just names, dates, and sometimes a parents occupation.

Then she found something promising.

Bumont Marie Clair, born November 3rd, 1885 to parents Etien Bumont and Josephine Bowmont, Navo, residence 427 Esplanade Avenue.

Vivienne pulled out her copy of the photograph.

The girl appeared to be about 10 years old in 1895, which would make her birth year approximately 1885.

The timing matched.

She searched for more records on ATN and Josephine Bowmont.

Etienne appeared in the 1890 city directory as a merchant and property owner with a business address on canal street.

Josephine’s name appeared in society notices in the New Orleans Daily Picune fundraising events for schools, church activities, charitable organizations.

This was definitely a prominent family.

But where had Marie Clare gotten those scars? Vivien requested adoption records next.

Louisiana had maintained formal adoption proceedings since the 1870s.

Though many adoptions in the Creole community were handled informally within extended families, the official records were incomplete.

But she found a document dated March 1891 that made her pulse quicken.

Petition for adoption.

Etienne and Josephine Bowmont seeking to legally adopt Marie Clare.

Approximate age 6 years.

Currently in their care.

Child’s origins unclear.

Petition granted.

April 1891.

The child’s origins were unclear.

At age 6 in 1891, Marie Clare had been formally adopted despite already being listed on an 1885 birth certificate as their biological daughter.

Something wasn’t adding up.

Vivien photographed the document and continued searching.

She needed to find out where Marie Clare had actually come from and how she had ended up with the Bowmonts.

In the property records, she found something else, a deed dated January 1891, showing Etienne Bowmont purchasing a small house in Plaamine Parish about 70 mi south of New Orleans.

The purchase price was listed as $800, a significant sum for what property maps showed was a modest structure.

Viven made notes.

Adoption finalized April 1891.

Property purchased January 1891, 3 months earlier.

Connection: Why would wealthy New Orleans merchant buy rural property in Plaamine Parish? She requested all available records from Plaamine Parish for 1890 1891 knowing it would take days to arrive.

Meanwhile, she had another resource to explore, the Feroh Photography Studio Records, if they still existed.

Armon Fau’s studio had operated on Royal Street from 1878 until his death in 1912.

His granddaughter had donated his business records to the historic New Orleans collection in the 1960s.

appointment books, client lists, financial ledgers, and remarkably, a detailed log describing each photograph taken.

Viven spent an afternoon in the collection’s reading room, carefully turning the pages of Pharaoh’s 1895 appointment book.

The entries were meticulous, written in precise French, dates, times, clients names, type of portrait, and often brief notes about the sitting.

She found the entry for November 1895.

Bumont family portrait.

MCU Etien Bowmont.

Madame Josephine Bowmont, daughter Marie Clare.

Full formal setting, three poses taken.

Client requested highest quality, important family record.

Payment $25.

$25 was expensive, equivalent to perhaps $800 in modern currency.

The Bowmonts had spared no expense, but it was Feralt’s personal notes written in smaller script at the bottom of the entry that made Vivien’s breath catch.

The child, very still, well behaved.

Madame Bowmont, particular about the girl’s collar, adjusted it multiple times before allowing exposure.

The child bears marks at the throat, visible despite careful positioning.

Did not inquire.

Family’s private matter, but such marks on one so young trouble the conscience.

Faux had seen the scars.

He had noticed them being deliberately concealed, and he had been troubled enough to record his observation.

Vivien checked the studio’s financial records.

In January 1891, the same month Etienne had purchased the plaque property, there was an entry showing a payment to Fau of $50 with the notation, special commission.

Discretion required.

No archive copies.

$50, twice the cost of the formal family portrait.

For what? What kind of photographic work required such discretion? Vivien’s mind raced with possibilities.

Had Faroh photographed Marie Clair when she first came to the Bmonts? Had he documented something that needed to be kept secret? The studio records indicated Pharaoh kept glass plate negatives of all his work stored in chronological order.

The collection’s curator had told Vivien that most plates from the 1890s survived, carefully preserved in acid-free storage.

She requested access to the January 1891 plates.

2 hours later, she sat at a light table with a box of glass negatives, each one carefully sleeved and labeled.

She worked through them chronologically.

January 16891, a wedding portrait.

January 5th, a family with three children.

January 9th, an elderly man in formal dress.

Then, dated January 12th, 1891.

A plate labeled only with a number.

Private commission 127.

Vivien lifted the plate carefully and held it to the light.

The image was a portrait of a small child.

perhaps five or six years old, standing against a plain backdrop.

The child wore a simple dress, her hair uncimemed and tangled, her expression was haunted, eyes wide, face thin, and around her neck clearly visible were the scars, letters and numbers.

M7J.

Vivian stared at the image, her hands trembling.

This was Marie Clare before the Bowmonts adopted her, before the fine dresses and careful hair styling, before the lace collars that hid her scars.

This was documentation of a rescued child.

Vivien drove south on Highway 1, following the Mississippi River through Louisiana’s sugarcane cutting.

The landscape was flat and green, broken by occasional clusters of houses and the rusting remains of old plantation infrastructure.

Plaamine Parish was rural, its economy still tied to agriculture as it had been for centuries.

The parish courthouse was a modest brick building in the town of Pllemine.

Viven had called ahead, and the clerk, a woman named Dorothy, who had worked there for 30 years, had pulled the records related to the property Etien Bowmont had purchased in 1891.

It’s unusual, Dorothy said, spreading documents across a table in the records room.

City folks didn’t typically buy property out here unless they had family connections or business interests.

And this particular piece of land, she pointed to a property map.

It wasn’t farmable, just a small house and a few acres of scrub land.

Vivien examined the deed.

The previous owner was listed as estate of Jacqu Mercier, deceased.

A note indicated the property had been seized for unpaid taxes and sold at auction, with ATN Bowmont being the only bidder.

Do you have any records on Jacqu Mercier? Vivienne asked.

Dorothy disappeared into the archives and returned with a slim folder.

Not much.

He died in 1890.

No known heirs.

The property went to the parish.

But there’s this.

She pulled out a sheriff’s report dated November 1890.

The report detailed a raid on Mercier’s property following complaints from neighbors.

What the sheriff found shocked Vivian.

Upon investigation of the Mercier residence discovered three negro children, ages approximately 4 or 8 years being held in conditions of servitude.

Children bore marks of branding and physical abuse.

Mercier claimed children were apprenticed to him legally, but could produce no documentation.

Children removed to parish custody.

Mercier charged with unlawful detention and assault.

Three children, one of them must have been Marie Clare.

Viven’s hands shook as she read further.

Children unable to provide information about their origins appear to have been taken at young ages with no memory of families.

Scars indicate they may have been marked by previous capttors.

Investigation into broader trafficking operation recommended.

What happened to Jacqu Mercer? Vivien asked.

Dorothy checked her notes.

Died in parish jail before trial.

Heart failure according to the death certificate.

The case was closed and the children were placed in an orphanage in New Orleans.

St.

Mary’s home for colored children.

Vivien felt pieces clicking into place.

Mary Clare had been rescued from Mercier’s house in late 1890.

Placed in an orphanage and then adopted by the Bowmonts in early 1891.

But why had it purchased Mercier’s property? She found the answer in a legal document dated February 1891.

Testimony of Etien Bowmont in the matter of children rescued from Jacqu Mercier property.

Mr.

Bumont states that upon learning of children held in Plaine Parish.

He investigated the matter personally.

He purchased the Mercier property in order to secure any evidence or documentation that might identify the children or their origins.

Among items found in the house were ledgers indicating Mercier had been part of a larger operation kidnapping freeborn negro children and selling them into illegal servitude.

Etien had bought the property to find evidence.

He had been trying to solve the mystery of where these children came from.

Back in New Orleans, Vivien requested all available records from St.

Mary’s home for colored children.

The orphanage had closed in 1924.

Its records transferred to the Catholic Arch Dascese.

Most had been damaged in Hurricane Betsy in 1965, but some ledgers and correspondents survived.

What she found was heartbreaking and infuriating in equal measure.

The intake records from November 1890 listed three children brought from Plaine Parish.

Child one, female, approximately 6 years, unable to state name, bears marking M7Js on neck.

Child two, male, approximately eight years, unable to state name, bears marking M4P on shoulder.

Child three, female, approximately four years, unable to state name, bears marking M2K on back.

The children had been so young when taken that they couldn’t remember their own names or where they’d come from.

They had been reduced to numbers and letters branded into their skin.

Vivien found correspondents from the orphanage director to various authorities, desperately trying to identify the children and find their families.

One letter to the New Orleans Police Department dated December 1890 detailed the problem.

We believe these children were kidnapped from their families and held in servitude, part of a criminal enterprise that may involve numerous perpetrators across multiple parishes.

The marks on their bodies suggest systematic identification, possibly indicating many more victims.

We implore your department to investigate thoroughly.

The police response was cursory.

Matter investigated.

No evidence of broader conspiracy.

Children likely orphaned by yellow fever or other epidemic.

taken in by Mercier with good intentions.

Unfortunate situation, but no crime proven.

No crime proven.

Despite the scars, despite the conditions the children were found in, despite everything.

But Etien Bowmont hadn’t accepted that conclusion.

Viven found more evidence of his personal investigation.

Letters he’d written to sheriffs across Louisiana asking about missing children, about similar cases, about anyone who might recognize the marking patterns.

One response from a sheriff in St.

James Parish dated March 1891 provided a lead.

We had a similar case in 1888.

Family reported their daughter taken from a church picnic.

Girl, aged three, name of Clara.

Never found her.

But the description of the markings you describe matches a child seen at a work camp up river.

The camp was raided, but most children there had been moved before we arrived.

Only found two boys, both too traumatized to speak.

Vivien spent the next week tracking down every reference to missing children in Louisiana between 1885 and 1890.

The pattern that emerged was chilling.

Dozens of reports of children disappearing, mostly from poor rural families.

mostly very young.

The cases were rarely investigated thoroughly.

When children were found in situations of illegal servitude, they were placed in orphanages, but almost never reunited with their families.

The marking system suggested organization.

M7J likely meant something.

Maybe the M indicated the trafficker mercier.

The number indicated sequence or location, and the letter indicated what? Age group, gender, destination.

Vivian found a report from a federal investigator dated 1892, a full year after Marie Cla’s adoption, that outlined a network of kidnapping and reinslavement operating across the South.

The investigator estimated hundreds of children had been taken and sold to farms, work camps, and private households as unpaid labor.

The report concluded with a bitter note.

Despite clear evidence of systematic child trafficking, local authorities show little interest in prosecution.

Many victims are from families too poor or powerless to demand justice.

This investigation is hereby closed due to lack of cooperation from local officials.

Viven found Etien Bowmont’s personal papers in the archives of the Amastad Research Center at Tulain University.

The collection included business correspondents, property records, and significantly a private journal he’d kept from 1890 to 1895.

She requested the journal and waited anxiously as it was retrieved from climate controlled storage.

The leatherbound book was fragile.

Its pages yellowed but still legible.

Etien’s handwriting was elegant and precise.

His entries detailed and often emotional.

The entry dated November 20th, 1890, made Vivien’s eyes well with tears.

Today, I learned of the children found in Plaamine.

Three souls stolen from their families, marked like animals, used as slaves 30 years after emancipation supposedly ended such horrors.

The police say there is nothing to be done.

The man who held them is dead.

The children cannot remember their origins.

They will go to an orphanage and likely never know who they truly are.

I cannot accept this.

Josephine and I have been blessed with wealth and position.

If we do not use these advantages to fight such injustice, what purpose does our prosperity serve? I have resolved to investigate personally.

If these children have families searching for them, I will find those families.

Over the following months, Etien documented his investigation.

He visited the Mercier property and found ledgers hidden in a false floor, records of children taken, dates, locations, and buyers.

He copied everything and turned the originals over to federal authorities, though he noted bitterly that he had little faith in their willingness to act.

The entry dated January 10th, 1891, described meeting Marie Clare for the first time at St.

Mary’s orphanage.

The child they call number seven is small for her age with large eyes that have seen too much suffering.

When I showed her the ledger entries, trying to find anything that might identify her origins, she touched the marking on her neck and said only, “Mama,” cried it is the first personal memory she has shared with anyone at the orphanage.

The marking reads M7J.

According to Mercier’s ledgers, she was acquired in July 1887 near Tibido.

Age approximately two years.

The J may indicate July.

The seller was listed only as Dupon, likely an alias.

I have written to authorities in Lefor Parish asking about any reports of a missing child from that time.

Viven flipped ahead through the journal.

Etien’s investigation consumed him.

He traveled across southern Louisiana, interviewed dozens of families who had lost children, and spent enormous sums hiring private investigators.

He found the families of the two other children rescued from Mercier’s house and facilitated emotional reunions, but Murie Cla’s family remained elusive.

No one in Tibido or surrounding areas recognized her description or the circumstances of her disappearance.

The trail went cold.

The entry dated March 15th, 1891, detailed a painful decision.

After 4 months of searching, I have found no trace of Mary Cla’s family.

It is possible they died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1888.

It is possible they moved away or that the records were simply lost.

I cannot continue the search indefinitely.

And meanwhile, the child remains in an orphanage waiting.

Josephine and I have decided to adopt her.

We will give her our name, our home, our love.

We will tell her the truth about where she came from when she’s old enough to understand.

And we will never stop hoping that someday somehow her original family might be found.

Viven’s research took an unexpected turn when she received an email from a descendant of the Bumont family.

Margaret Tibido, a retired teacher living in Lafayette, had seen a news article about Viven’s work with the Louisiana Historical Archives and recognized her great great-grandmother’s maiden name, Bowmont.

They met at a cafe in the French Quarter.

Margaret brought a box of family papers that had been in her attic for decades, letters, photographs, and documents passed down through generations, but never properly examined.

My grandmother always said there were family secrets, Margaret explained.

But she died before she could tell me what they were.

Maybe these papers will help.

Vivien opened the box carefully.

Inside were bundles of letters tied with ribbon organized by date.

Most were routine family correspondents, but one bundle stood out.

Letters between Josephine Bowmont and a woman named Sister Marie TZ, a nun who had worked at St.

Mary’s orphanage.

The letters dated from 1895 to 1910, long after Marie Cla’s adoption.

Vivienne read through them, finding discussions of orphanage fundraising, church events, and social matters.

But then she found a letter from 1897 that made her heart race.

Dear Josephine, I write with news that may bring both joy and sorrow.

A woman came to the orphanage yesterday asking about children who passed through our care in 1890.

She has been searching for her daughter taken from her in Tibido in 1887 when the child was just 2 years old.

The woman was herself enslaved at that time, illegally held on a remote farm despite the war’s end.

She escaped in 1889, but was unable to return for her daughter until she had established herself in New Orleans and earned enough money to hire an investigator.

She described a small mark her daughter had, a birthark shaped like a crescent moon on the child’s left shoulder blade.

She also remembered that when the child was taken, the man who took her was called Dupon, though she believes this was a false name.

Josephine, I believe this woman may be Marie Clare’s mother.

I did not tell her anything definitive, but I gave her your address.

I hope I have not overstepped, but a mother’s love deserves the chance to be reunited with her child.

Vivian’s hands trembled.

Marie Clare’s mother had found her.

After 10 years of separation, after escaping illegal enslavement herself, after years of searching, she had tracked down her daughter.

But what had happened then? Had Josephine allowed the reunion? Had Mary Clare, raised as a bowont for six years, remembered her birthother.

Vivien found the answer in the next letter, dated two weeks later, written in Josephine’s hand.

Dear sister Marie TZ, I must tell you what transpired when Claudine Tibido came to our home.

I admit I felt fear at first.

Fear that we would lose Mary Clare, whom we love as dearly as if she had been born to us.

But when Cladine saw Mary Clare and Mary Clare saw her, something extraordinary happened.

The child, who had no conscious memory of her mother, ran to her immediately.

She said, “You’re the lady from my dreams.

” They held each other and wept, and I wept with them.

Huh.

Vivien continued reading Josephine’s letter, tears streaming down her face.

Etienne and I faced an impossible decision.

Legally, Mary Clare is our adopted daughter.

We could have refused to allow Claudine any access to her, but how could we deny a mother who had suffered so much to find her child? How could we deny Mary Clare the chance to know her birthother? We invited Claudine to stay with us for several days so she and Mary Clare could spend time together.

The stories Claudine told were heartbreaking.

She had been born free in Tibido in 1865, immediately after emancipation.

Her parents died of fever when she was young, and at age 16, she was tricked by a man offering employment and instead imprisoned on a remote farm.

Forced to work without pay, she became pregnant, an assault by the farm’s overseer and gave birth to Mary Clare in 1885.

For 2 years, she cared for her daughter while planning escape.

But when Mary Clare was two, the child was taken from her and sold to a man Claudine knew only as Dupon.

Cladine was told if she tried to escape or report what had happened, her daughter would be killed.

She finally escaped in 1889 when the farm’s owner died and his estate was sold.

She made her way to New Orleans with nothing, took work as a laundress, saved every penny, and eventually hired an investigator.

It took 8 years to find her daughter.

Mary Clare sat with her mother for hours, asking questions, holding her hand, examining her face as if memorizing every feature.

And then my daughter, our daughter, asked the question we had been dreading.

Do I have to leave, Papaen and Mama Josephine? The room fell silent.

Claudine looked at me with tears in her eyes and said, “No, my darling, you don’t have to leave.

You have been blessed with two mothers and two fathers who love you.

I only want to be part of your life if you’ll have me.

” And so, we have made an arrangement that defies convention, but feels right in our hearts.

Cludine has taken a room near our home.

She visits Marie Clare every week.

Marie Clare calls her mama Claudine and calls me Mama Josephine.

The child now has two families and we are all richer for it.

Margaret wiped her eyes.

I never knew any of this.

My grandmother spoke of Cludine as Aunt Claudine, a family friend.

I had no idea she was Marie Clare’s birthother.

Vivien found more letters documenting this unusual arrangement.

Cladine became part of the Bowmont household’s extended family.

She taught Marie Clair traditional Creole songs, told her stories of their Tibido ancestors, and gave her the truth about where she came from.

In an 1899 letter, Josephine wrote, “Mary Clare is now 14 and understands the full story of her early years.

She knows about the kidnapping, the trafficking, the illegal enslavement.

She knows about the scars on her neck and what they represent.

We feared this knowledge would traumatize her, but instead she has become passionate about justice.

” She speaks of becoming a lawyer or a teacher of helping other children who have been wronged.

Vivian found a photograph tucked into the letters, a group portrait from 1900 showing the Bowmont family gathered in their parlor.

Etienne and Josephine sat in chairs.

Marie Clare stood between them, now a young woman of 15.

And beside Josephine stood another woman, older, her face bearing the marks of hardship, but her eyes bright with joy.

Claudine Tibidau, Marie Cla’s first mother, finally united with her daughter.

3 months after discovering the Bumont family photograph, Viven stood before a packed auditorium at Tulain University, preparing to present her findings.

The event had drawn historians, genealogologists, descendants of Louisiana’s Creole families, and activists working on issues of child trafficking and exploitation.

On the screen behind her was the original 1895 photograph, the Bowmonts in their elegant parlor, Marie Clair in her lace colored dress.

But now, thanks to digital enhancement, a second image appeared beside it.

A close-up of Marie Cla’s neck, the scars visible, the letters M7J clear enough to read.

This photograph, Vivien began, is about concealment and revelation.

The Bumonts carefully posed their daughter to hide her scars, evidence of a traumatic past they wanted to protect her from.

But they also preserved evidence of that past, perhaps knowing that someday the truth would need to be told.

She clicked to the next slide, the 1891 photograph of Marie Clare before her adoption.

Thin and haunted, her scars fully visible.

Between these two images lies a story of extraordinary courage from multiple people.

Jacques Mercier, who kidnapped and held children in illegal servitude.

Etienne and Josephine Bowmont, who used their privilege to investigate his crimes and rescue the children.

Claudine Tibido, who survived enslavement herself and never stopped searching for her stolen daughter, and Mary Clare, who endured trauma that would have broken many people, but instead built a life of purpose and advocacy.

Pakias, Viven showed documents from her research, Etienne’s journal entries, the ledgers from Mercier’s house, the letters between Josephine and Sister Marie TZ, the photograph of the two families united.

What makes this story particularly important, she continued, is that it reveals a largely undocumented aspect of post civil war history.

We know that slavery legally ended in 1865, but illegal enslavement continued for decades, particularly in the South.

Children were especially vulnerable, kidnapped from poor families, marked like property, sold into servitude on remote farms where authorities rarely ventured.

The Bumont’s investigation uncovered a network that operated across Louisiana involving dozens of perpetrators and potentially hundreds of victims.

Most of these children were never reunited with their families.

Their stories died with them.

But Marie Cla’s story survived because people cared enough to document it, to preserve evidence, and to fight for justice even when authorities wouldn’t.

She showed a final image, a newspaper article from 1915.

The headline read, “Attorney Marie Cla Bumont Tibido wins landmark case for child labor protections.

” Marie Cla grew up to become one of Louisiana’s first black female lawyers.

Vivian explained she specialized in cases involving child exploitation and illegal labor practices.

She successfully prosecuted several child trafficking operations and helped reunite over 30 children with their families.

The scars she bore became her motivation to ensure other children wouldn’t suffer as she had.

Margaret Tibido stood from the front row.

I’d like to add something if I may.

She joined Viven at the podium.

Mar Clair was my great-g grandandmother.

She passed away in 1963 at the age of 78.

I knew her when I was young, though she never spoke to me about her early years.

But she left behind journals and letters that my family is now prepared to donate to the Louisiana Historical Archives.

In those documents, she wrote extensively about her two mothers, about the Bumont family’s efforts to find trafficked children, and about Claudine’s determination to never give up searching.

There’s one passage I want to share.

Kings and Margaret unfolded a paper and read, “I have two mothers, and I am blessed by both.

Mama Claudine gave me life and never stopped fighting to find me.

Mama Josephine gave me safety and opportunity and never stopped fighting to reunite me with my first family.

Together, they taught me that love is not diminished by being shared.

It multiplies.

And they taught me that privilege means nothing if it’s not used to help those who suffer.

The audience sat in silence for a moment, then erupted in applause.

After the presentation, Vivien was approached by several people with similar stories.

families who suspected their ancestors had been victims of post-emancipation trafficking.

Descendants seeking to understand mysterious scars and old photographs, researchers working on related topics.

But the most meaningful encounter came from an elderly woman who waited until everyone else had left.

She introduced herself as Clara Dupi and handed Vivian a photograph in a worn envelope.

“This is my grandmother,” she said, pointing to a young girl in the photo, maybe six or seven years old.

“She was found at a work camp in St.

James Parish in 1888.

She had marks on her shoulder.

M4P.

She never found her original family, but maybe with your help, we could try.

Vivien looked at the photograph, then at Clara’s hopeful face.

M4P matched the marking on one of the other children rescued from Mercier’s house.

One of the two children whose families Etien Bowmont had successfully found.

I think we can, Vivien said.

In fact, I think we might already have a lead, she thought of Marie Clare, standing between her two mothers in that 1900 photograph, whole and healed despite the scars she carried.

The photograph in Vivian’s office, the one that had started this entire investigation, was no longer just an image of concealment.

It was a testament to resilience, to the power of investigative persistence, and to the revolutionary idea that families could be built on love rather than blood alone.

The scars hidden beneath Marie Cla’s lace collar had told a story that waited 129 years to be fully heard.

And now finally people were listening.

News

Archaeologists Just Discovered Something Beneath Jesus’ Tomb In Jerusalem… And It’s Bad

In Jerusalem, where history is layered as densely as the stone beneath its streets, a recent discovery has reopened questions…

Pope Leo XIV Declares The Antichrist Has Already Spoken From Within the Holy City A statement attributed to Pope Leo XIV has sent shockwaves through religious circles after reports claimed he warned that a deceptive voice had already emerged from within the Holy City itself. Was this meant as a literal declaration, a symbolic admonition, or a theological reflection on MORAL DECEPTION and SPIRITUAL AUTHORITY in modern times? As theologians dissect the language and believers debate its meaning, questions are rising about PROPHECY, INTERPRETATION, and WHY SUCH WORDS WOULD BE SPOKEN NOW.

With official clarifications limited and reactions intensifying, the message has ignited one of the most unsettling conversations the Church has faced in years.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Examine What Was Said—and How Different Voices Are Interpreting It.

In the quiet hours before dawn on January third, a sequence of events began inside the Vatican that would soon…

Pope Leo XIV Bans Popular Marian Devotion and Bishops Around the World React in Fury Reports circulating across Church networks claim Pope Leo XIV has restricted or banned a Marian devotion practiced widely in multiple regions—a move that allegedly triggered sharp backlash from bishops and clergy worldwide. What exactly was limited, why was the devotion targeted, and does this represent doctrinal clarification or disciplinary overreach? As statements and reactions pour in, divisions are emerging over TRADITION, AUTHORITY, and THE LIMITS OF PAPAL POWER.

With official explanations still unfolding and emotions running high, the controversy is quickly becoming a defining test of unity within the global Church.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Explore What’s Being Said—and Why the Reaction Has Been So Intense.

The marble floors of the papal residence reflected pale moonlight in the early hours before dawn. Pope Leo the Fourteenth…

Pope Leo XIV Ousts Influential Cardinals—Unveils Decades of Vatican Corruption Sources close to Vatican observers claim a dramatic internal shake-up followed decisions attributed to Pope Leo XIV—moves that allegedly sidelined several influential cardinals while reopening scrutiny into long-buried financial and administrative practices. What actions were actually taken, which allegations are supported by documentation, and how far back do the claims of misconduct reach? As senior officials rush to control the narrative, the moment has reignited debate over TRANSPARENCY, REFORM, and WHETHER THE CHURCH IS ENTERING A RECKONING LONG DELAYED.

With statements carefully worded and details emerging slowly, speculation continues to grow about how deep this crisis may run.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Examine What’s Being Reported—and What Remains Unconfirmed.

Pope Leo XIV Initiates Unprecedented Vatican Financial Reckoning Amid Internal Resistance In the early hours of the morning, when Vatican…

Pope Leo XIV Issues 12 New Rules for Mass—Catholics Struggle to Accept Sudden Liturgical Reform Reports circulating within Church circles claim Pope Leo XIV has introduced a set of 12 new guidelines affecting how Mass is celebrated—a move that has reportedly caught many clergy and lay Catholics off guard. What do these proposed changes involve, why were they introduced so abruptly, and how do they interact with long-standing liturgical traditions? As parishes react with confusion, concern, and cautious support, the discussion has quickly expanded to questions of AUTHORITY, CONTINUITY, and HOW MUCH CHANGE THE FAITHFUL CAN ABSORB AT ONCE.

With official explanations still unfolding, the reforms are already igniting one of the most intense liturgical debates in recent memory.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Explore the Rules Being Discussed—and Why Reactions Are So Divided.

Pope Leo I XIV Prepares to Reshape Catholic Worship as Vatican Debates Historic Liturgical Reform The final light of a…

Pope Leo XIV Shatters Vatican Financial Secrecy Pillar — Cardinals Scramble to Contain Fallout According to reports circulating among Vatican analysts, Pope Leo XIV has taken a dramatic step that may have dismantled a long-standing pillar of financial secrecy within the Holy See. Sources suggest the move triggered urgent meetings and behind-the-scenes efforts by senior cardinals to manage potential repercussions.

What exactly was revealed or restructured, why was this moment chosen, and how deep could the consequences run for Church governance and global trust? As officials issue carefully worded statements, questions intensify around TRANSPARENCY, ACCOUNTABILITY, and WHETHER THIS SIGNALS A NEW ERA—or a deepening internal rift.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Examine What Changed—and Why the Fallout Is Spreading Fast.

Secret Vatican Decree Triggers Internal Crisis and Redefines the Future of Church Governance In the early hours before dawn, within…

End of content

No more pages to load