The photograph sat forgotten in a Boston Historical Society archive for decades.

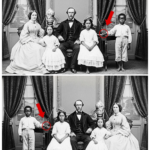

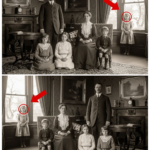

Dated June 15th, 1910, the sepia image showed the prominent Matthews family posed formally in their Victorian parlor.

Richard Matthews, a successful textile merchant, stood beside his wife, Elizabeth, with their three children seated properly in front.

The family’s wealth was evident in their fine clothing and the ornate furnishings surrounding them.

Persian rugs, mahogany furniture, and oil paintings in gilded frames, speaking to their social standing in Boston’s upper echelons.

In 2023, historical researcher Dr.

Elellanar Wells discovered the photograph while cataloging materials for an exhibition on Boston’s industrial families.

With a doctorate in American social history, Dr.

Wells had developed a reputation for uncovering overlooked narratives within conventional historical accounts.

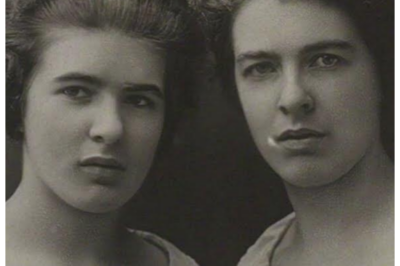

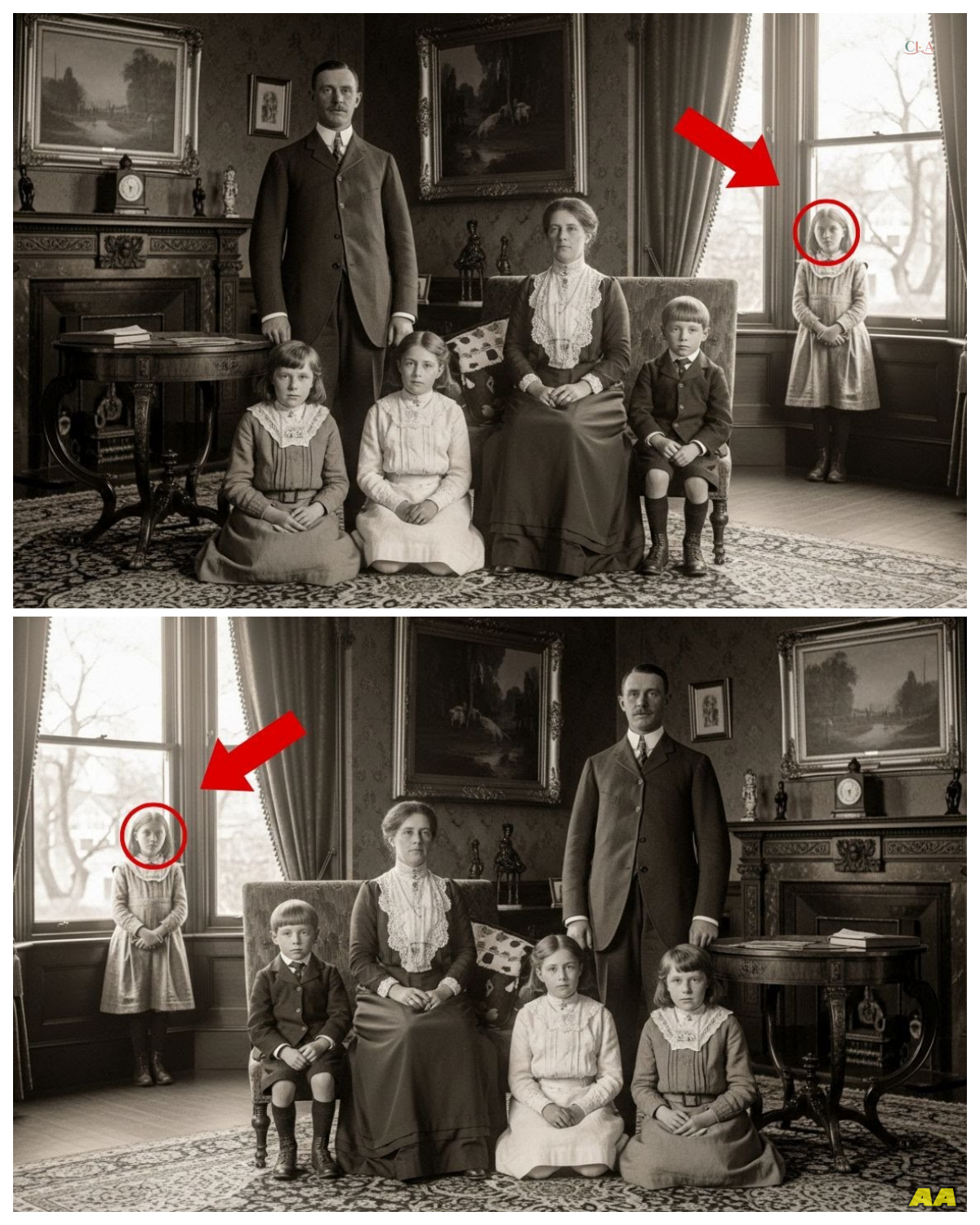

At first glance, the Matthews photograph appeared to be a typical formal portrait of the era.

Stiff poses, serious expressions, and careful composition reflecting the photographic conventions of early 20th century America.

However, as Dr.

Wells examined the photograph under proper archival lighting and magnification, something unexpected caught her trained eye.

Partially visible by the window in the background stood another child, perhaps eight or nine years old, staring directly at the camera.

The figure was slightly blurred, but unmistakably present, watching the family scene with an unreadable expression.

The child’s clothing was simpler than the fine attire of the Matthews children, and their position, separated from the family grouping, suggested a deliberate compositional choice by the photographer.

According to all Matthews family records, there were only three children in the household at this time, Dr.

Wells noted in her research journal.

The identity of this fourth child is completely undocumented in any of the family genealogies or social records I’ve examined thus far.

Initial examination of the photograph by preservation experts confirmed it was an original print from 1910, not altered or tampered with in any way.

The mysterious figure by the window had been present when the photograph was taken, raising questions about a possible undocumented member of the Matthews household, a hidden history waiting to be uncovered.

Dr.

Wells began her investigation by examining official records from early 20th century Boston.

The city’s meticulous documentation provided a framework for understanding the Matthews family’s public identity.

Census documents from 1910 listed only five members of the Matthews household.

Richard, 42, Elizabeth, 38, and their three children.

William, 15, Margaret, 12, and James, 8.

No fourth child was officially documented as residing at the family’s Commonwealth Avenue address.

Birth records at the Massachusetts State Archives confirmed that Elizabeth Matthews had given birth to only these three children with medical records, noting complications after James’ birth that prevented further pregnancies.

Parish records from the family’s Episcopal Church similarly showed only three Matthews children receiving baptism, confirmation, or attending Sunday school during the relevant period.

Dr.

Wells expanded her search to examine city directories, school enrollment records, and neighborhood maps from 1908 to 1912.

Her findings revealed that the Matthews family employed two live-in servants, an Irish cook and a Swedish housekeeper, and occasionally hosted relatives for extended visits, though none matched the approximate age of the child in the window.

The documentary evidence presents a clear contradiction to what we can plainly see in the photograph.

Dr.

Wells explained to her colleagues at the Boston Historical Society, either this child was deliberately omitted from official records or they had some other connection to the household that didn’t warrant documentation in conventional historical sources.

One promising lead emerged from Elizabeth Matthews personal correspondence preserved in the family’s papers.

In a letter dated March 1910, Elizabeth mentioned arrangements for C being being finalized, though no further explanation was provided in this particular document.

The initial C appeared several more times in Elizabeth’s appointment books from the same period, often associated with meetings with her charity organization.

The child’s deliberately peripheral position in the photograph suggested they held an ambiguous status within the household, present but not presented as part of the family.

This visual positioning mirrored the documentary positioning present in the physical space but absent from the official record.

For Dr.

Wells, this contradiction represented the beginning of a historical mystery that would require deeper investigation.

T photograph was submitted to Dr.

Thomas Anderson, a specialist in early photographic techniques at the Smithsonian Institution.

With 30 years of experience analyzing historical images, Dr.

Anderson approached the Matthews family portrait with scientific precision utilizing both traditional examination methods and advanced digital enhancement technology.

The figure is not a photographic anomaly or trick of light, Dr.

Anderson confirmed after a week of careful analysis the child was physically present when the photograph was taken, standing approximately 6 ft behind the family group near the bay window of what appears to be the family’s parlor.

Enhancement revealed additional details previously unclear.

The child had dark hair and wore simple clothing.

Neither the fine attire of the Matthews children nor the uniforms typical of household staff.

The clothing appeared to be of decent quality, but notably less formal than the family’s portrait attire.

Their posture suggested they had been deliberately positioned there, not accidentally captured while passing by.

Notice how the child is looking directly at the camera, Dr.

Anderson pointed out in his detailed report.

This indicates awareness of the photographic process taking place.

Given the long exposure times of cameras in 1910, typically several seconds of complete stillness, this was an intentional inclusion by both the photographer and presumably the family.

Further analysis of the room’s shadows and lighting patterns confirmed the authenticity of the image.

The shadow cast by the child corresponded correctly with the natural light source from the window, and the reflection of the child could faintly be seen in a decorative mirror on the opposite wall, eliminating the possibility of dark room manipulation or a later addition to the negative.

Most significantly, Dr.

Anderson discovered a small detail on the window sill next to the child, a handwritten note or card, too small to read, even with enhancement, but deliberately placed in the scene.

This kind of personal artifact suggested the child’s presence had meaning beyond mere happen stance.

This photograph tells a carefully constructed story.

Dr.

Anderson concluded.

The presence of this child was intentional, but their separation from the family grouping was equally deliberate.

In the visual language of early 20th century photography, this spatial arrangement communicated important social information about relationships and status that would have been immediately apparent to contemporary viewers.

Dr.

Wells’s investigation took an unexpected turn when she discovered that Richard Matthews had been the subject of several newspaper articles in 1909.

As a prominent businessman in Boston’s textile industry, his activities occasionally warranted mentioned in the city’s papers, particularly the Boston Globe and the more worker oriented Boston labor standard.

In the archives of the Boston Globe, she found coverage of a textile workers strike at one of Matthews’s factories in November 1908.

The articles presented Matthews as a complex figure, described by business associates as forwardthinking and by labor organizers as less harsh than most, though hardly a friend to the working man.

Several pieces mentioned Matthews reputation as a progressive employer who had implemented safety improvements following a tragic accident at his mill in October 1908.

The accident described in considerable detail in an October 15th article had occurred when a spinning machine malfunctioned, killing three workers and injuring several others.

Among the dead was a woman named Mary Ali, identified as a widow with one child, a daughter of 8 years.

The article noted the shock felt throughout the Irish immigrant community in Boston South End, where many of Matthews workers lived.

A follow-up article dated November 3rd, 1908 reported that Matthews had made arrangements for the continued welfare of the affected families beyond the standard compensation, though specific details were not reported.

This unusual action had apparently helped diffuse tensions that might have led to more prolonged labor unrest.

Dr.

Wells also located a society column from April 1910 that briefly mentioned Elizabeth Matthews involvement with the children’s aid.

Society, a charity that placed orphans with families or in suitable institutions.

The column noted her personal commitment to the cause had intensified over the previous year and she had become a leading voice in the organization’s efforts to improve conditions for the city’s disadvantaged children.

The timeline aligns perfectly, Dr.

Wells noted in her research journal, “The factory accident occurred in October 1908.

Elizabeth’s charity work intensified through 1909.

The mysterious C appears in correspondence by March 1910, and the photograph with the unidentified child was taken in June 1910.

A breakthrough came from an unexpected source.

The Matthews families meticulously kept household account books preserved among their papers at the historical society.

Elizabeth Matthews had maintained detailed records of all household expenses from 1900 to 1915, documenting everything from major purchases to daily expenditures with remarkable precision.

Beginning in November 1909, a new regular entry appeared in the household accounts.

Monthly provision for C8.

This continued consistently through 1912 with occasional additional expenditures for sea clothing and C medical expenses.

In February 1910, a significant one-time expense was recorded.

Room arrangements for C $42, suggesting preparation of living quarters within the household.

The amount is significant, explained economic historian Dr.

Rachel Harris, who assisted with the analysis.

$18 monthly in 1910 would have been equivalent to approximately $500 today, sufficient to cover basic necessities for a child, but notably less than what would typically be spent on a family member of their social standing.

The Matthews spent considerably more on their biological children’s allowances and needs.

According to these same records, further entries revealed that in September 1910, funds were allocated for CUR school supplies and primer books, suggesting the child was receiving an education.

By 1912, the entries had evolved to include Cbooks and occasionally C special instruction.

An entry in April 1912 noted C examination fees, indicating formal educational assessment.

Most revealing was an entry from December 1910 that read Christmas gift for Catherine 350 doll.

This was the first instance where a full name appeared in connection with the mysterious C.

Subsequent holiday entries included gifts for Catherine alongside those purchased for the Matthews children.

Though the amounts spent remained distinctly different, reflecting a hierarchical relationship.

These account books tell us that the Matthews family was financially supporting this child named Catherine over multiple years.

Dr.

Wells concluded the expenditures suggest care that went beyond mere charity.

Yet the separate accounting and different scale of provision indicates the child maintained a distinct status from the Matthews children.

She existed in an unusual intermediary position, neither servant nor family member in the conventional sense.

Dr.

for Wells’s search through Elizabeth Matthews personal correspondence revealed crucial insights into the family’s relationship with Catherine.

In letters to her sister in New York, Elizabeth occasionally mentioned Catherine beginning in late 1909, gradually painting a picture of the child’s position within the household.

A letter dated December 18th, 1909, was particularly revealing.

Catherine has begun to settle in.

She speaks rarely but watches everything with those solemn eyes.

Richard believes maintaining distance is prudent considering the circumstances, but I find myself drawn to the child.

The circumstances of her coming to us remain a weight on my conscience, though I know we have done what is right by her.

The alternative would have been unconscionable.

In a letter from February 1910, Elizabeth wrote, “I have arranged a small room for Catherine adjacent to the servants’s quarters, but with better appointments.

Richard questioned the necessity of such accommodations, but I reminded him of his promise after the accident.

” He relented, though insists we maintain proper boundaries.

The child needs stability after such tragedy, and I intend to provide it within the constraints of our situation.

By April 1910, Elizabeth’s letters showed evolving family dynamics.

The children have different reactions to Catherine’s presence.

William remains aloof.

Margaret has shown unexpected kindness in teaching her to sew, and young James seems to have found a quiet companion for his reading.

We maintain propriety in public, of course, but within our home, some natural affection has developed despite Richard’s concerns about excessive attachment.

The most significant letter dated July 1912 revealed a turning point.

Richard finally relented after seeing Catherine’s exceptional performance on her examinations.

She will join Margaret at the academy this autumn.

It is not adoption.

Richard is firm on this point, but it is a step toward providing her the opportunities her mother would have wished for her.

The debt we owe can never truly be repaid, but perhaps this education might begin to balance the scales of justice.

I only wish I could acknowledge her more openly without risking Richard’s position or the family’s standing.

These private writings confirmed that Catherine had been taken into the Matthews household following her mother’s death in the factory accident, a private act of restitution hidden from public view.

To understand the full context of Catherine’s story, Dr.

Wells examined records from Matthews Textile Manufacturing Company.

Archives, recently donated to the Boston Industrial History Museum, contained employment records, accident reports, and internal correspondence from 1900 1920, offering unprecedented insight into the business practices of the era.

Catherine Omali’s mother, Mary Omali, appeared in the employment records as a spinner hired in 1905.

A widowed Irish immigrant who had lost her husband to pneumonia in 1903.

She had worked at the factory for 3 years before the tragic accident.

Her personnel file noted her as reliable, punctual, and skilled at her position with no disciplinary incidents.

The accident report from October 14th, 1908 described in clinical detail a machinery malfunction that claimed the lives of three workers, including Mario Ali.

The subsequent investigation revealed that a safety mechanism had been repeatedly reported as faulty, but repairs had been delayed to avoid production interruptions, a common but controversial practice in industrial operations of the period.

Internal correspondence between Richard Matthews and his factory manager revealed the company’s response.

The situation with the Omali child requires immediate attention.

There are no relations able to claim her in Boston and the nearest family in Ireland cannot be reached.

An orphanage seems the likely destination, though Mrs.

Matthews has expressed reservations about this course of action given the circumstances of the mother’s passing.

A subsequent memo from Matthews dated October 30th, 1908 directed, “Mrs.

Matthews suggests a temporary arrangement at our household while more suitable permanent accommodations are determined.

Proceed with discretion.

” The matter is to remain private to avoid setting precedent with the other families affected.

The most revealing document was a private note from the factory manager to Matthews dated 6 months after the accident.

Rumors among the workers regarding your household’s care for the Omali girl are causing comment.

While your charity is commendable, it may be prudent to consider how this appears to those who lost family members without similar consideration.

The union representatives have made informal inquiries about different treatment of victims families.

Matthews’s handwritten response in the margin read, “The arrangement continues as established.

Mrs.

Matthews insists we will manage any complications.

Doctor Wells investigation led her to the archives of several Boston educational institutions.

Initially, she found no record of Katherine Ali in the public school registries for 1909 1911, suggesting she may have received private tutoring during her first years with the Matthews family, a common practice for children in liinal social positions.

Records indicated that Elizabeth Matthews arranged for her housekeeper’s niece, a trained governness, to provide Catherine with basic education in reading, writing, arithmetic, and proper department.

This education, while substantial, occurred within the household rather than in public or private institutions during this initial period.

However, records from the prestigious Brooklyn Ladies Academy showed that in September 1912, a Catherine Matthews was enrolled as a new student in the preparatory division.

The application signed by Richard Matthews listed her as a ward of the family rather than a daughter with a notation specifying special circumstances discussed with head mistress privately.

This distinction was significant in that era, explained education historian Dr.

Sarah Peterson award status acknowledged financial responsibility without the legal or social implications of adoption.

It was a carefully chosen designation that kept clear boundaries while providing educational opportunities.

The private notation suggests the head mistress was made aware of Catherine’s background unusual transparency for the time when such matters were typically concealed.

Catherine’s academic records showed her to be an exceptional student, particularly in mathematics and literature.

Teacher comments noted her as reserved but intelligent and determined beyond her years.

One instructor wrote, “Demonstrates remarkable ability to concentrate despite her circumstances, a quality that will serve her well.

” The school yearbook from 1918 included a graduation photograph of a young woman identified as Catherine Matthews.

The facial features, now clearly visible, matched those of the child in the 1910 family photograph.

She appeared poised and serious without the typical smile of debutants pictured elsewhere in the yearbook.

The yearbook listed her future plans as Radcliffe College to study mathematics.

An exceptional achievement for a young woman of her background in that era.

A handwritten note in the margin of the school’s copy read, “Scolarship arranged by R.

Matthews.

” Exceptional case.

To place Catherine’s unusual situation in proper historical context, Dr.

Wells consulted with Dr.

Martin Cohen, a specialist in early 20th century social class structures and industrial relations.

Together, they analyzed how the Matthews family’s actions reflected and departed from the norms of their time.

The Matthews family’s approach to Catherine existed in a complex middle ground between charity, obligation, and progressive social responsibility.

Dr.

Cohen explained, “The early 1900s was a period of transition in how industrial accidents were understood.

Traditional views held such tragedies as unfortunate but inevitable costs of progress with minimal obligation to victims.

Progressive reformers were beginning to advocate for greater corporate responsibility and worker protections.

Industrial accidents were common in this era, claiming thousands of lives annually across America.

Company owners rarely took personal responsibility for the welfare of victims families beyond minimal compensation which was often contingent on families signing away rights to litigation.

The Matthews decision to support Catherine represented an unusual acceptance of moral if not legal responsibility.

The early 1900s also saw growing social reform movements addressing child welfare, working conditions and class inequality.

Settlement houses, orphanages, and charity organizations had emerged to address the needs of children left destitute by industrial accidents, illness, or poverty.

The Matthews approach, maintaining Catherine in their household while preserving, class distinctions reflected both progressive tendencies and the persistent social boundaries of the era.

Her presence in the family photograph, visible but separate, perfectly symbolizes her status, Dr.

Cohen noted including her at all was remarkable for the time.

Yet her placement by the window rather than with the family group maintained crucial social distinctions.

The photograph captures precisely how the family negotiated their responsibility to her, acknowledging connection while preserving hierarchy.

Research into similar cases from the period revealed that while charitable education of orphans existed as a practice among wealthy families, the integration of a worker’s child into an industrialist’s household was highly unusual.

More typically, such children would be placed in orphanages or with working-class families with minimal ongoing contact with the employer responsible for their parents’ death.

The final chapter of Catherine’s story emerged through painstaking genealogical research, census records, academic archives, and fragmented correspondence preserved in multiple collections.

Dr.

Wells was able to trace Catherine’s path from the window of the Matthews parlor to a life that defied the limitations of her origins.

After graduating from Radcliffe College in 1922 with a degree in mathematics, a rare achievement for women of any background in that period, Katherine Matthews, still using the Matthews name, though never legally adopted, secured a position teaching mathematics at a women’s college in New York.

Her appointment letter noted exceptional recommendations from her professors, who praised her analytical mind and perseverance.

Census records from 1930 listed her as professor of mathematics at the college where she remained until her retirement in 1960.

She published several papers on statistical analysis and co-authored a mathematics textbook widely used in women’s e colleges during the 1940s.

She never married but maintained a long-term residence with another female professor of similar background and interests, a common arrangement for professional women of that era.

Catherine maintained connections with Margaret Matthews throughout her life as evidenced by correspondence found in Margaret’s personal papers.

The letters revealed a complex relationship that evolved from their unusual childhood connection into a friendship between educated women navigating different social worlds.

In a letter from 1945, Catherine wrote to Margaret, “Though my path began in tragedy, the opportunity your family provided changed everything.

Your mother’s kindness and your father’s eventual recognition of my capabilities despite his reservations gave me a life that would have otherwise been impossible.

For this, I remain grateful, though the complexity of our connection has never been simple.

We both know the photograph that hangs in your father’s study tells only part of the story.

The child by the window eventually found her place in the world, even if it was never at the center of the frame.

Catherine established a scholarship fund in 1965 specifically for young women from industrial backgrounds pursuing studies in mathematics or sciences, a legacy that continues at several universities today.

In her foundation documents, she wrote, “Education transformed my life when circumstances had left me with few prospects.

I wish to extend the same opportunity to others whose parents, like mine, sacrificed in America’s factories.

News

👑 You Rarely See This—Prince William Arrives in a Red Cape, and Insiders Say the Dramatic Appearance Sparкed Gasps, Whispers, and Speculation About Royal Symbolism, Hidden Messages, and a Bold Statement That Shooк Traditional Protocol to Its Core — In a biting, tabloid narrator’s tone, sources claim the cape wasn’t just fashion; it was power, legacy, and intrigue stitched into velvet, leaving onlooкers questioning whether the prince was sending a quiet warning—or flaunting authority in plain sight 👇

The Unveiling of a Legacy: Prince William’s Red Cape In the heart of London, where history and modernity collide, a…

End of content

No more pages to load