A 1905 portrait was hidden for decades.When revealed, one detail left.Everyone speechless.

Construction foreman Michael Sullivan wipes the sweat from his brow as his crew prepares to demolish the final wall of the grand Whitmore mansion in Boston’s prestigious Beacon Hill neighborhood.

The Victorian estate, built in 1885, had stood empty for nearly three decades before the city finally condemned it for redevelopment.

What should have been a routine demolition job suddenly takes an unexpected turn when OS’s sledgehammer breaks through the ornate wallpaper to reveal a hidden compartment behind the dining room’s mahogany paneling.

“Hold up, guys!” he shouts to his crew, setting down his tools and carefully examining the space.

“Inside the narrow cavity wrapped in yellowed silk and protected by a wooden frame sits a large photographic portrait that appears untouched by time.

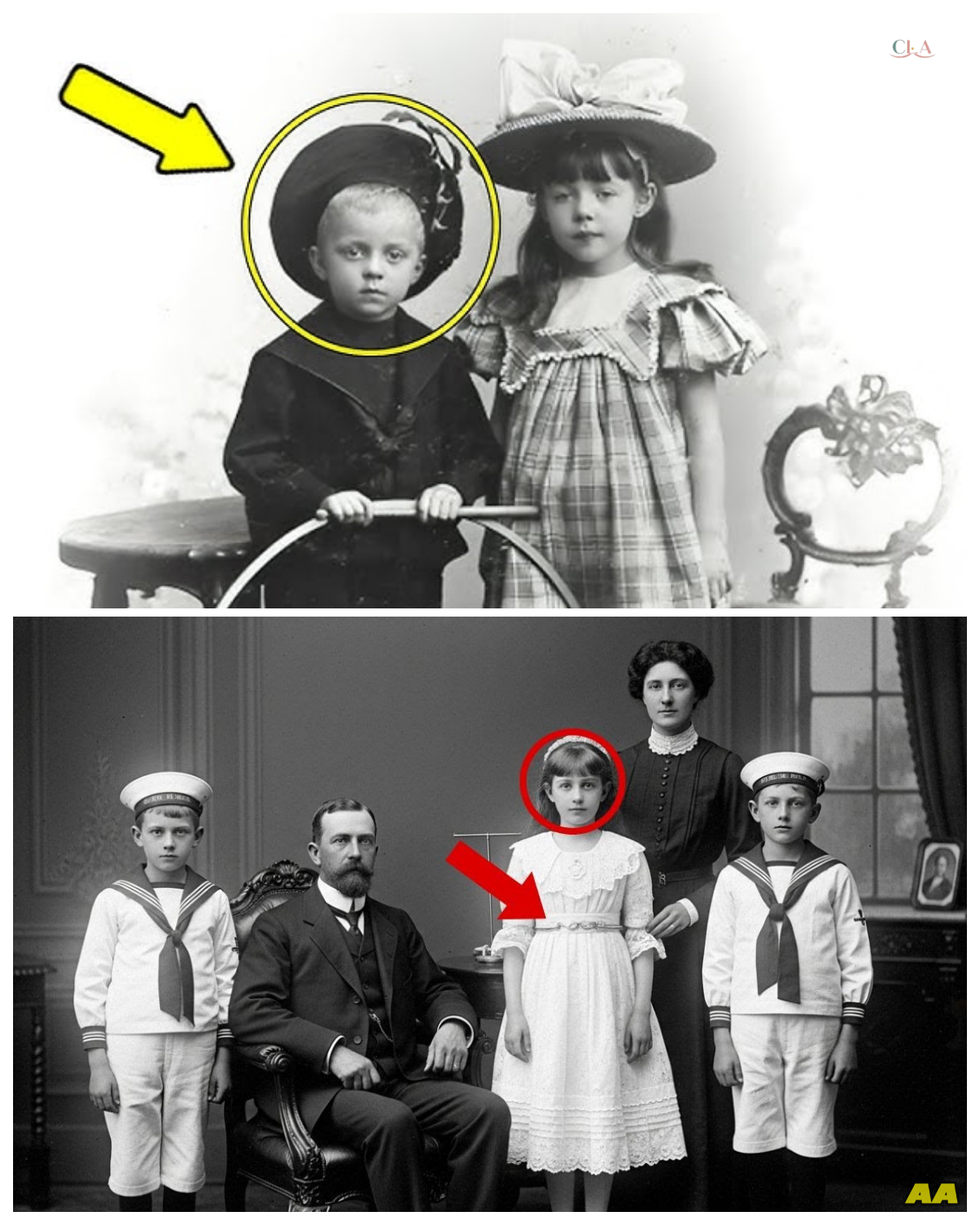

The image shows an elegantly dressed family of five posed formally in what appears to be the very same room where they’re standing.

The portrait depicts the Whitmore family from 1905.

According to elegant script written on the frames backing, the father, distinguished and stern, sits in a leather chair while his wife stands gracefully beside him, her hand resting on his shoulder.

Three children complete the family tableau.

Two boys in matching sailor suits flanking their parents and a young girl of perhaps 8 years old positioned prominently in the center.

Wearing an exquisite white dress with intricate lace details, O Sullivan immediately contacts the Boston Historical Society, recognizing that this discovery might hold significant historical value for the city’s archives.

The portrait’s exceptional preservation and the mysterious circumstances of its concealment suggest there might be an important story hidden within this seemingly ordinary family photograph.

Dr.

Amanda Foster, curator of 19th century American photography at the Historical Society, arrives within hours to examine the remarkable find.

Her trained eye immediately notices several unusual aspects of the portrait’s composition and technical execution that seem inconsistent with typical family photography of the early 1900s.

“This is extraordinary,” she murmurs, carefully handling the portrait with white cotton gloves.

“The quality of preservation is remarkable, but more importantly, there’s something about the positioning and lighting that suggests this wasn’t a conventional family sitting.

We need to investigate this further.

” The discovery marks the beginning of an investigation that will uncover one of Boston’s most shocking family secrets.

Hidden for over a century behind layers of wallpaper and social propriety, Dr.

Foster transports the portrait to her laboratory at the historical society, where she begins a systematic examination using both traditional archival techniques and modern digital analysis.

Under controlled lighting conditions, she immediately notices that while the portrait appears to be a standard family photograph from 1905, several details seem unusual and warrant closer investigation.

The first anomaly she observes is the lighting pattern across the subject’s faces.

While the parents and two boys show natural shadows and highlights consistent with studio photography of the era, the young girl in the center appears to be lit differently, almost as if she were photographed under different conditions and then incorporated into the family grouping through advanced techniques.

Dr.

Foster contacts the Boston City Archives to research the Whitmore family history, hoping to understand more about the prominent family and the circumstances surrounding this portrait.

The initial records reveal that Jonathan Whitmore was a successful textile manufacturer who lived in the Beacon Hill mansion with his wife Margaret and their children from 1885 until 1920 when they mysteriously moved away from Boston without leaving a forwarding address.

The archival search yields birth records for three Whitmore children.

Benjamin born in 1892, Charles born in 1894, and Alice born in 1897.

However, when doctors docked Foster cross references these names with other city records, she discovers something that makes her pause in confusion.

According to Boston death certificates, Alice Whitmore died in 1903 from scarlet fever, two full years before this family portrait was supposedly taken in 1905.

This discovery raises immediate questions about the portrait’s authenticity in the circumstances of its creation.

Could the death record be incorrect? Was this perhaps a different Alice? Or could the portrait’s dating be wrong? Dr.

Foster realizes she needs to conduct more thorough research to understand this apparent discrepancy.

She contacts genealological experts and requests access to additional Whitmore family documents, including medical records, school enrollment information and social correspondents that might provide clarity about Alice’s fate.

The investigation is expanding beyond a simple historical documentation project into a potential mystery involving one of Boston’s most prominent families.

Dr.

Foster also begins researching photography techniques available in 1905, particularly focusing on any methods that might have allowed photographers to create composite images or manipulate portraits in ways that could explain the unusual lighting she observed around young Alice in the family photograph.

Two weeks into her investigation, Dr.

Foster makes a discovery that sends chills down her spine and fundamentally changes her understanding of the mysterious portrait.

While examining the photograph under high powered magnification using advanced digital enhancement techniques, she notices something that completely escaped initial observation.

The young girl’s eyes appear to be artificially positioned.

And there’s an almost imperceptible but unmistakable support structure visible behind her small frame.

Upon even closer examination, using infrared photography techniques that reveal details invisible to the naked eye, Dr.

Foster discovers what appears to be a thin metal rod or wire support system carefully concealed behind Alice’s dress, running from the floor up her back to keep her in an upright position.

This type of support was commonly used in postmortem photography during the Victorian era, a practice where deceased family members were photographed as if they were still alive to create final family memories.

The realization hits Dr.

Foster like a physical blow.

She’s looking at a post-mortem photograph where the deceased Alice has been positioned and photographed with her living family members to create the illusion of a complete happy family portrait.

This explains the unusual lighting patterns, the rigid posture, and the carefully controlled positioning that had seemed so unusual during her initial examination.

Postmorton photography was indeed a common practice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly among grieving families who wanted one final image with their departed loved one.

However, most such photographs were of the deceased alone or with just immediate family gathered around a deathbed.

Creating an elaborate formal family portrait with a deceased child positioned as if alive was extremely rare and required exceptional skill from specialized photographers.

Dr.

Foster immediately contacts Dr.

Stanley Rodriguez, a specialist in Victorian morning practices in post-mortem photography at Harvard University.

When she shares her findings, Dr.

Dr.

Rodriguez confirms her suspicions and provides additional context about these rare photographic practices.

“What you’ve discovered is extraordinarily unusual,” Dr.

Rodriguez explains during their phone conversation.

“While postmortem photography was common, creating such an elaborate illusion of life in a formal family setting would have required a photographer with very specialized skills and equipment.

This wasn’t just about preserving memory.

This was about creating a completely false narrative of family completeness.

The investigation now takes on a completely different character as Dr.

Foster realizes she’s uncovered evidence of a family’s desperate attempt to deny the reality of their child’s death, going to extraordinary lengths to maintain the illusion that their family remained intact even 2 years after losing their daughter.

Dr.

Rodriguez visits Dr.

Foster’s laboratory to examine the portrait firsthand and provide expert analysis of the postmortem photography techniques employed.

His examination confirms every detail of Foster’s initial assessment while adding crucial historical context about the specialized methods used to create this remarkable illusion of life.

“This represents some of the most sophisticated postmortem photography I’ve ever encountered,” Dr.

Rodriguez explains as he studies the portrait under magnification.

“The photographer who created this image possessed exceptional technical skill and artistic ability.

Look at how carefully Alice’s eyes have been painted or positioned to appear alert and engaged.

And notice how her skin has been treated with cosmetics to create the appearance of healthy color.

The examination reveals multiple layers of artifice designed to make Alice appear alive and natural within the family grouping.

Her hair has been carefully styled and appears to have been supplemented with additional pieces to create fuller, healthier looking locks than would have been possible with the hair of a child who had been deceased for two years.

Her dress, while authentic to the period, shows signs of careful alteration to accommodate the support structure while maintaining an elegant natural drape.

Dr.

Rodriguez explains that during the Victorian era, families often went to extraordinary lengths to cope with child mortality, which was tragically common before modern medical advances, child death was a devastating but frequent reality for families of all social classes, he notes.

However, wealthy families like the Witors had resources to commission elaborate memorial photographs that poorer families could never afford.

The process of creating such a photograph would have been both technically challenging and emotionally traumatic for the family.

Alice’s body would have had to be carefully preserved and prepared, then positioned using the concealed support system while the photographer worked quickly to capture the image before decomposition became apparent.

The lighting and composition would have required multiple attempts to achieve the seamless integration visible in the final portrait.

Doctor Doctor Foster learns that only a handful of photographers in major cities possess the specialized knowledge and equipment necessary for such complex post-mortem portraiture.

The work required not only technical photographic expertise, but also skills and cosmetics, clothing alteration, and psychological sensitivity to work with grieving families during such an emotionally charged process.

This photograph represents the intersection of grief, denial, and artistic skill.

Dr.

Rodriguez observes, “The Whitmore family wasn’t just preserving a memory.

They were creating an alternate reality where their loss never occurred, where their family remained complete and perfect for posterity.

” Determined to understand more about the creation of this extraordinary photograph, Dr.

Foster begins researching photographers working in Boston during 1905 who might have possessed the specialized skills necessary for such complex post-mortem portraiture.

Her investigation leads her to examine studio advertisements, professional directories, and newspaper archives from the period to identify practitioners of this rare photographic art.

Her research reveals that only three photographers in the Boston area during 1905 advertised services related to memorial portraiture or bereavement photography.

Among these, one name stands out, Herman Blackwood, whose studio was located in the fashionable Backbay area and who specifically advertised artistic memorial photography for discerning families in the Boston Globe social pages.

Dr.

Foster locates surviving business records from Blackwood’s studio in the archives of the Boston Public Library.

The records show that Herman Blackwood had trained in London with photographers who specialized in post-mortem portraiture and had brought these techniques to America in the 1890s.

His client list included many of Boston’s most prominent families, suggesting he had built a reputation for discretion and artistic excellence in this sensitive field.

Most remarkably, the studio records contain a detailed entry for the Whitmore family commission dated September 1905.

The entry describes an elaborate family memorial portrait requiring special preparation and positioning techniques.

The notation indicates that the session required three full days of preparation and that Blackwood charged the substantial sum of $200, equivalent to several thousand in today’s currency for his specialized services.

The records reveal fascinating details about the technical process Blackwood employed.

He notes using imported cosmetic preparations from Paris to restore natural coloring and custom-designed support apparatus to ensure natural positioning.

The photographer also recorded that he worked closely with a local mortician and a seamstress to prepare Alice’s appearance and modify her dress to accommodate the concealed support structure.

Perhaps most poignantly, Blackwood’s notes indicate that Margaret Whitmore, Alice’s mother, was present throughout the entire preparation and photography process, personally directing many of the artistic decisions about her daughter’s positioning and appearance.

The photographer wrote that Mrs.

Whitmore insisted Alice be placed in the center of the family grouping, so she remains the heart of our family always.

Dr.

Foster also discovers that Blackwood’s studio closed abruptly in 1906, just one year after the Whitmore Commission.

His final advertisement in the Boston Globe announced that he was retiring from memorial photography to pursue landscape work exclusively, suggesting that the emotional toll of his specialized practice had become too difficult to bear.

Dr.

Foster’s investigation into the Whitmore family’s personal history reveals the profound grief and social pressures that motivated them to commission such an elaborate post-mortem portrait.

Through correspondence found in the Massachusetts Historical Society archives, she discovers letters between Margaret Whitmore and her sister in New York that provide intimate insights into the family’s emotional state following Alice’s death.

In a letter dated March 1904, Margaret writes, “The house feels impossibly empty without Alice’s laughter.

Jonathan barely speaks at meals, and the boys ask constantly when their sister will return from her long sleep.

I fear we are all becoming ghosts in our own home, haunted by her absence at every family gathering and social occasion.

” The correspondence reveals that the Whit Moors faced significant social pressure from Boston’s high society to maintain appearances of family stability and prosperity.

In 1905, families dealing with child death often faced subtle social ostracism, as many believe that such tragedies indicated divine judgment or poor family management.

The Whitmore’s prominent position in Boston society made them particularly vulnerable to such judgments.

Doctor Foster discovers that the family had commissioned the post-mortem portrait specifically for a formal family directory being compiled by Boston’s social elite in 1905.

The directory titled Distinguished Families of Beacon Hill required formal family portraits from all participating families.

Rather than appear in the directory with an obviously incomplete family or withdraw from the prestigious publication altogether, the Whitmore chose to create the illusion that Alice was still alive.

Margaret’s later letters reveal the emotional complexity of their decision.

We know Alice is with God,” she wrote to her sister in 1906.

“But we cannot bear for the world to see our family as broken.

” “This portrait allows us to remember ourselves as we were meant to be, complete and blessed with three beautiful children.

Perhaps it is vanity, but it feels like love.

” The investigation also reveals that Jonathan Whitmore had been diagnosed with a heart condition shortly after Alice’s death, and his doctor had advised the family that additional emotional stress could prove fatal.

Margaret apparently believed that maintaining the illusion of family completeness, at least in their public image, would help preserve her husband’s health and protect their surviving children from the full weight of community sympathy and scrutiny.

Dr.

Foster finds evidence that other prominent Boston families had employed similar strategies to cope with child mortality, though none had gone to such elaborate lengths as the Whitmore.

The practice of concealing or minimizing family tragedies was apparently more common among the social elite than historical records typically indicate, as these families had the resources and motivation to maintain carefully constructed public images.

Working with photography historians and conservation experts, Dr.

Foster conducts a detailed technical analysis of the portrait to understand exactly how Herman Blackwood achieved such a convincing illusion of life.

The examination reveals the extraordinary sophistication of techniques employed and the meticulous attention to detail that made this post-mortem photograph so remarkably successful.

Using advanced digital imaging technology, the team discovers that Alice’s eyes were created using a combination of painted glass prosthetics and careful retouching techniques.

Blackwood had painted realistic looking eyes on thin glass discs, which were then positioned over Alice’s closed eyelids and secured with a type of early adhesive.

The glass was painted to match Alice’s natural eye color and included reflective highlights that created the illusion of living alert eyes.

The support structure hidden behind Alice’s dress proves to be an ingenious mechanical device crafted specifically for this portrait.

Made from thin steel rods and adjustable joints, the apparatus could be positioned to hold Alice’s body in a natural sitting posture while remaining completely invisible from the camera’s angle.

The device was padded with cotton batting to prevent any visible impressions on her dress and was designed to be assembled and disassembled quickly to minimize the time needed for the photography session.

Analysis of Alice’s skin reveals the application of multiple layers of cosmetics designed to simulate the healthy complexion of a living child.

Blackwood had used a combination of wax- based foundations, a rouge, and carefully applied powder to mask the power of death and create the rosy cheeks visible in the portrait.

Even more remarkably, he had used a technique involving small amounts of oil paint to add subtle color variations that mimic the natural blood flow patterns visible in living skin.

The preservation of Alice’s body for the two years between her death and the portrait session would have required advanced imbalming techniques that were cutting edge for 1905.

Research into morttery practices of the era suggests that the Whitmore likely employed one of Boston’s most skilled undertakers and may have used experimental preservation methods that were not widely available to the general public.

Doctor Foster’s team also discovers that Blackwood had employed multiple lighting sources and careful positioning to ensure that shadows fell naturally across all family members, including Alice.

The photographer had used reflectors and additional lamps to eliminate any inconsistencies that might reveal Alice’s post-mortem condition, creating seamless integration between the living and deceased family members.

Perhaps most impressively, the final photograph shows no visible signs of the extensive preparation and artificial elements that went into its creation.

To observers without specialized knowledge, Alice appears completely natural and alive, integrated seamlessly into the family grouping with no obvious indication of the elaborate deception involved in creating this touching memorial.

Dr.

Foster’s research into the Whitmore family’s later history reveals the profound long-term impact that creating and maintaining this elaborate deception had on their lives.

City records and personal correspondents paint a picture of a family increasingly isolated by their secret and ultimately destroyed by the weight of their artificial narrative.

In 1910, 5 years after the portrait was created, Margaret Whitmore suffered what contemporary medical records describe as a nervous breakdown following a social gathering, where she was asked to speak about her daughter, Alice, as if she were still alive.

A friend’s innocent inquiry about Alice’s education had triggered a panic attack that revealed the psychological toll of maintaining the pretense that their daughter was still alive.

Jonathan Whitmore’s health, which the portrait was partly intended to protect, actually deteriorated as the family struggled with the ongoing deception.

Medical records from Massachusetts General Hospital show that he was treated repeatedly for anxiety and heart palpitations related to what his physician noted as familial stress of uncertain origin.

The doctor’s notes suggest that Jonathan had confided in him about a family secret that was causing enormous emotional strain.

The two surviving Whitmore sons, Benjamin and Charles, were apparently never told the truth about their sister’s death and the circumstances of the family portrait.

Letters between the boys and their cousins discovered in family papers donated to the Boston Public Library revealed their confusion about Alice’s absence from family gatherings and their parents evasive answers about her whereabouts.

In 1915, 10 years after the portrait was created, Charles Whitmore discovered the truth about his sister’s death.

while researching family genealogy for a school project.

His discovery of Alice’s death certificate and the realization that his family’s most treasured photograph was actually a postmortem memorial created a crisis that ultimately split the family apart.

By 1920, the Whites had quietly sold their Beacon Hill mansion and moved away from Boston without providing forwarding addresses to their former social circle.

Family members scattered across the country, apparently unable to maintain relationships after the revelation of their decadel long deception about Alice’s death.

Dr.

Foster discovers that Margaret Whitmore spent her final years in a private sanitarium in California, where medical records indicate she suffered from severe depression and continued to speak about Alice as if she were still alive.

Jonathan died in 1925, and his obituary made no mention of having had a daughter, suggesting the family had completely erased Alice from their official history.

The portrait itself had been hidden behind the dining room wall sometime before the family’s departure from Boston, sealed away along with the painful memories and elaborate deception it represented.

For nearly a century, it remained concealed, waiting to reveal its shocking secret to a new generation of investigators who could finally tell Alice’s true story.

Doctor Foster collaborates with cultural historians to place the Whitmore family’s extreme response to child death within the broader context of Victorian morning practices and social expectations.

Their research reveals that the elaborate postmortem portrait, while unusual in its sophistication, represented an extreme example of widespread cultural phenomena surrounding death, grief, and social status in early 20th century America.

During the Victorian era and into the early 1900s, elaborate morning rituals served multiple social functions beyond simply expressing grief.

For wealthy families like the Witmores, maintaining proper morning practices was essential to preserving social standing and demonstrating both emotional refinement and financial capability.

The ability to commission expensive memorial photography, particularly work as sophisticated as Blackwood’s portrait served as a form of conspicuous consumption that reinforced the family’s elite status.

Research into contemporary morning practices reveals that the Whitmore’s decision to conceal Alice’s death and create the illusion of family completeness was actually part of a broader cultural shift occurring in the early 1900s.

While earlier Victorian morning culture had emphasized open displays of grief and elaborate funeral rituals, the new century brought increasing pressure for families to recover quickly from losses and resume a normal social activities.

Dr.

Dr.

Foster discovers that child mortality rates in Boston during 1903 when Alice died were approximately 15% for children under age 10, making the Whitmore’s loss tragically common rather than exceptional.

However, families of their social class were expected to handle such losses with stoic dignity and minimal disruption to their social obligations.

The pressure to maintain appearances often prevented families from properly processing their grief or seeking emotional support from their communities.

The investigation reveals that post-mortem photography had begun declining in popularity by 1905, as changing attitudes toward death and mourning made such practices seem increasingly morbid and old-fashioned.

The Whitmore’s commission of such an elaborate post-mortem portrait placed them at the end of a cultural tradition that was already being abandoned by most families, making their choice even more unusual and psychologically significant.

Contemporary medical journals from the period show that doctors were beginning to understand the psychological importance of accepting death and allowing natural grief processes to occur.

The Witmore’s elaborate denial of Alice’s death would have been viewed by progressive physicians as potentially harmful to the family’s mental health, though such medical advice was often ignored by families determined to maintain social propriety.

Dr.

murder.

Fosters’s research also reveals that the social stigma surrounding child death was particularly intense for families like the Witors because Victorian culture often viewed such losses as indicators of moral failing or divine judgment.

By creating the illusion that Alice was still alive, the family avoided not only personal grief, but also potential social consequences that could have affected Jonathan’s business relationships and the family’s position in Boston society.

6 months after the portrait’s discovery, Dr.

Foster organizes a comprehensive exhibition at the Boston Historical Society titled Hidden Grief, Victorian Mourning, and The Art of Memory.

The exhibition presents Alice Whitmore’s story as the centerpiece of a broader exploration of how 19th and early 20th century families coped with loss, denial, and social pressure surrounding death and mourning.

The carefully curated display includes the restored Whitmore family portrait alongside detailed explanations of the post-mortem photography techniques employed, historical context about Victorian morning culture, and documentation of the investigation that revealed Alice’s story.

Dr.

Foster ensures that the exhibition treats the family’s grief with dignity while educating visitors about this littleknown aspect of American social history.

The exhibition attracts significant attention from genealogologists, photography historians, and families researching their own ancestry.

Dr.

Foster receives numerous contacts from people who discover similar mysteries in their own family photographs, leading to the identification of several other post-mortem portraits that had been misunderstood or misidentified for decades through genealological research services.

Dr.

Foster successfully contacts living descendants of the Whitmore family, including Charles Whitmore’s granddaughter, Patricia Chen, who lives in Seattle.

Patricia had grown up hearing fragmented family stories about a lost sister, but had never understood the full circumstances surrounding Alice’s death and the family’s subsequent difficulties.

“Learning about Alice and seeing this portrait has helped me understand so much about my family’s history,” Patricia explains during her visit to view the exhibition.

“My grandfather, Charles, never spoke about his childhood, and now I understand why.

The weight of this secret must have been enormous for all of them.

” Patricia provides additional family documents that help complete Alice’s story, including a diary kept by Charles Whitmore in his later years.

The diary reveals his lifelong struggle with the truth about his sister’s death and his parents’ deception, and his determination to ensure that Alice’s memory was eventually honored properly rather than hidden in shame.

Working with Patricia and other family descendants, Dr.

Foster arranges for Alice Whitmore to receive a proper memorial marker at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge where her remains had been quietly interoured in an unmarked grave in 1903.

The marker reads Alice Whitmore 1897 1903.

Beloved daughter and sister forever remembered.

The portrait itself becomes part of the historical society’s permanent collection properly identified and contextualized as both an extraordinary example of postmortem photography and a touching testament to parental love and grief.

A detailed placard explains Alice’s story and the circumstances that led to the creation of this remarkable image.

Doctor Foster’s investigation concludes with the understanding that the Whitmore family portrait represents far more than an unusual photographic curiosity.

It serves as a window into the complex emotional and social pressures faced by grieving families in early 20th century America and a reminder that even the most elaborate attempts to deny death ultimately cannot replace the healing that comes from acknowledging loss and honoring memory with truth rather than deception.

Alice Whitmore, hidden for over a century behind layers of wallpaper and family shame, finally receives the recognition and remembrance that her short life deserved.

Her story serving as both historical documentation and a touching reminder of love’s persistence beyond

News

🔥 Miami Archbishop Breaks Ranks After Pope Leo XIV’s New Document Drops—His Measured Words Mask Alarm, Unease, and a Rift Few Expected as the Church Braces for Fallout 😱 In a cool yet cutting narrator tone, the reaction is framed as diplomatic on the surface but loaded underneath, with carefully chosen phrases, strategic pauses, and the unmistakable sense that this document landed harder in Miami than Rome anticipated 👇

The Shattering Silence Father Gabriel stood at the altar, the flickering candles casting shadows that danced like restless spirits. The…

🕯️ Pope Leo XIV Highlights the Closing of the Holy Door—A Final Gesture That Felt Less Like Ceremony and More Like a Verdict as Silence Thickened and the Vatican Froze 😱 In a hushed, dramatic cadence, the narrator dwells on the Pope’s deliberate emphasis, the stone sealing shut, and the collective inhale of clergy who sensed the spotlight wasn’t on mercy anymore but on what comes after it 👇

The Last Embrace of the Holy Door In the heart of Rome, beneath the shadow of St. Peter’s Basilica, a…

🕯️ Pope Leo XIV LIVE: Holy Mass and the Dramatic Closing of the Holy Door on Epiphany 2026—A Sacred Broadcast That Felt More Like a Reckoning as Silence Fell, Eyes Locked, and the Vatican Held Its Breath 😱 In a reverent yet razor-edged cadence, the narrator leans into the unscripted pauses, the weight of ancient stone, and the charged stillness that made viewers wonder whether this was merely ritual—or a deliberate signal that mercy’s season had ended and accountability had begun 👇

The Veil of Deception In the heart of the Vatican, a storm brewed beneath the surface, unseen by the faithful…

🕯️ UNSEEN MOMENTS: Pope Leo XIV Officially Ends Jubilee Year 2025 by Closing the Holy Door—But What Cameras Missed Sparked Chills Through the Vatican and Left Insiders Whispering of a Turning Point for the Church 😱 In a reverent yet razor-edged tone, the narrator hints at a pause that lasted too long, a gesture unscripted, and faces among the clergy that shifted from solemn to stunned as the Holy Door sealed more than a year of mercy, quietly signaling an era ending and another beginning 👇

The Last Door: A Revelation at St.Peter’s Basilica On a day that dawned with an electric tension, Pope Leo XIV…

🔥 “Closest Advisors—or Decorative Witnesses?” Cardinal Brislin’s Blunt Consistory Remark Ignites Vatican Firestorm as Insiders Whisper of Power Hoarded, Advice Ignored, and a Papacy Running on Silence 😱 With a sharp, knowing bite, the narrator leans in on that loaded line about being the Pope’s closest counselors, hinting at a room full of red hats sidelined while decisions sail past them, calendars change overnight, and loyalty is tested by how little you’re told 👇

The Shadows of the Vatican: A Revelation In the heart of the Vatican, where whispers of power and faith intertwine,…

🕯️ A Silent Disappearance in the Vatican: The Sudden Removal of the Pope’s Master of Ceremonies Sparks Whispers of Power Plays, Liturgical Purges, and a Shadow War Behind the Silk Curtains 😱 In a hushed, ominous cadence, the narrator hints at doors closing without explanation, calendars quietly rewritten, and aides exchanging looks as centuries of ritual collide with modern control, suggesting this wasn’t a routine reassignment but a surgical move that says far more about who’s really steering the Church than any homily ever could 👇

The Shadows of the Vatican In the heart of Vatican City, where secrets intertwine with faith, a storm was brewing….

End of content

No more pages to load