In a cluttered antique shop in downtown Portland, Oregon, collector and historian Dr.Samuel Morrison made a discovery that would haunt him for months.

Among a collection of family photographs purchased from an estate sale, one image immediately caught his attention.

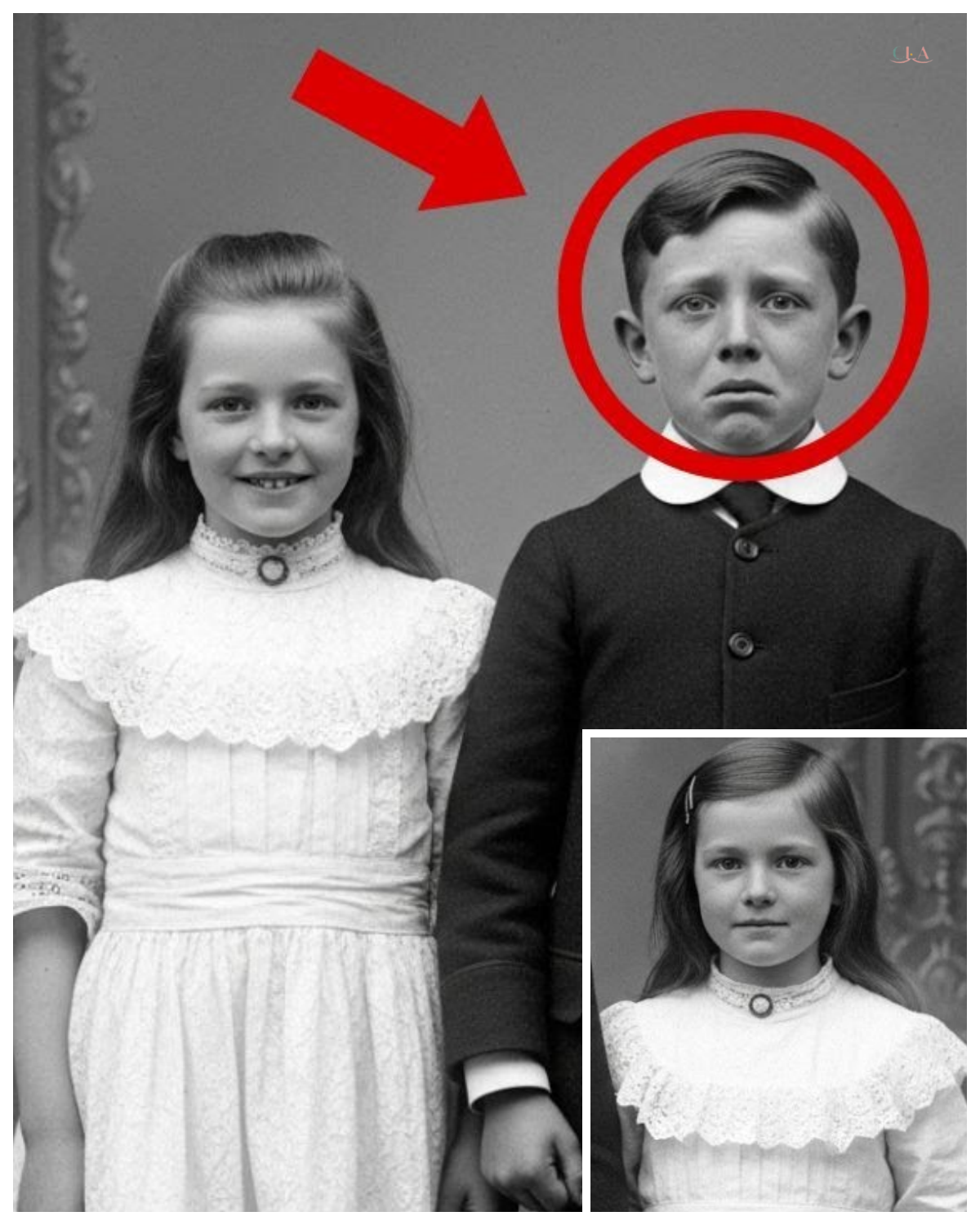

The formal studio portrait mounted on thick cardboard typical of early 1900s photography showed three children posed against an elaborate Victorian backdrop.

The inscription on the back written in careful script read, “Dorothy, 8, Thomas, 12, Helen, 6, Portland Studio, 1904.

” At first glance, the photograph appeared to be a typical family portrait of the era.

Two young girls in pristine white lace dresses flanked their older brother, who wore a dark wool suit with a starched white collar.

The girls smiled naturally, their eyes bright with the innocent joy of childhood.

But something about the boy’s expression troubled Dr.

Morrison.

While Thomas’s mouth curved upward in what should have been a cheerful smile, his eyes told a different story.

There was a depth of sadness, perhaps even fear, that seemed incompatible with the formal celebration the photograph was meant to capture.

The contrast was subtle but unmistakable to Morrison’s trained eye, honed by decades of analyzing historical photographs for emotional and social context.

The lighting in the studio had been carefully arranged to flatter the subjects, casting soft shadows that should have created warmth and intimacy.

Yet Thomas appeared somehow separate from his sisters, as if he were enduring the session rather than enjoying it.

His small hands, visible at his sides, were clenched into fists, an unusual pose for formal portraiture of the time.

Dr.

Morrison had seen thousands of period photographs, but few had affected him so immediately.

Something about this boy’s expression suggested a story far more complex than a simple family portrait.

The photographer had captured a moment that revealed more than the family likely intended, preserving not just an image, but a mystery that had waited over a century to be solved.

As Morrison examined the photograph under his magnifying glass that evening, he noticed other details that deepened his curiosity.

The quality of the children’s clothing suggested a wealthy family.

Yet, there were subtle signs of wear on Thomas’s suit that weren’t present on the girls dresses.

More intriguingly, while the girls wore matching lockets, Thomas wore no jewelry at all.

Unusual for a family portrait where equality and prosperity were typically emphasized, the studios embossed mark in the corner identified it as Hoffman and Associates.

Fine portraiture, Portland, Oregon.

Morrison realized he had stumbled upon something that demanded investigation.

Dr.

Morrison’s research into Hoffman and Associates led him through Portland’s historical archives and city records.

The studio he discovered had operated from 1898 to 1912 on Southwest Morrison Street in what was then Portland’s bustling commercial district.

Hinrich Hoffman, a German immigrant, had established the business as one of the city’s premier photography studios, catering to wealthy families during Portland’s rapid expansion following the Oregon Gold Rush.

The Portland Historical Society’s archives contained dozens of Hoffman photographs, but none quite like the one Morrison had found.

Mrs.

Elellanar Vance, the society’s elderly archivist, had worked with the collection for over 30 years.

When Morrison showed her the photograph, her weathered hands trembled slightly as she examined it.

“I’ve seen thousands of Hoffman’s portraits,” she said, adjusting her glasses.

And he had a particular style, very formal, very proper.

But this one, she paused, studying Thomas’s face.

But there’s something different about this boy’s expression.

Hoffman was known for putting his subjects at ease, especially children.

This suggests something was troubling the child that even Hoffman couldn’t overcome.

The archives revealed that 1904 was a significant year in Portland’s history.

The Louiswis and Clark centennial exposition was being planned, bringing unprecedented prosperity to the city.

Wealthy families like the one in the photograph would have been eager to document their status and success.

Yet, this portrait seemed to tell a more complicated story.

Morrison discovered that Hoffman kept meticulous records of his sessions, including notes about his subjects and the circumstances of each photograph.

The studio’s log books, preserved in the Oregon Historical Society, might contain crucial information about the session that produced this haunting image.

After days of searching through handwritten entries, Morrison found the relevant page.

The entry dated September 15th, 1904, read, “Whit more children, Dorothy Thomas, Helen, father’s request.

Special circumstances payment in advance.

boy reluctant throughout session.

Unusual family dynamics observed.

The surname Whitmore opened new avenues of investigation.

Morrison realized he wasn’t just looking at a random family portrait, but a document of a specific Portland family during a particular moment in their history.

The photographers’s notes about special circumstances and the boy’s reluctance suggested that this wasn’t a typical family celebration.

Portland’s city directories from 1904 listed three Whitmore families, but only one with children matching the ages in the photograph.

Charles Whitmore, a successful timber merchant, lived in a mansion in Portland’s exclusive Knobill neighborhood with his wife, Catherine, and their three children.

The Whitmore name carried considerable weight in early 20th century Portland.

Charles Whitmore had arrived from Maine in 1887, drawn by Oregon’s booming timber industry.

Within 15 years, he had built one of the most successful lumber operations in the Pacific Northwest, supplying wood for the rapid construction that followed the completion of the transcontinental railroad.

Morrison’s investigation through Portland’s business records revealed that Charles Whitmore owned three sawmills, employed over 200 workers, and held contracts with the Southern Pacific Railroad.

The family lived in a grand Victorian mansion on Northwest Portland’s prestigious Knobill, complete with 10 bedrooms, formal gardens, and a staff of six servants.

Newspaper Society pages from 1904 frequently mentioned Katherine Whitmore’s charitable work and elaborate social gatherings.

The Portland Oregonian described her as one of our city’s most gracious hostesses.

regularly entertaining prominent businessmen, politicians, and visiting dignitaries.

The Whitmore appeared to embody the American success story, a self-made man building an empire while raising a proper family in Portland’s elite society.

Yet, the photograph suggested a different reality within the family’s private world.

Thomas’s expression contradicted everything the public records indicated about the Whitmore’s prosperity and happiness.

Morrison wondered what circumstances had led to that September day in Hoffman’s studio when a 12-year-old boy had struggled to smile for the camera.

Further research revealed that 1904 was a pivotal year for the Whitmore business empire.

Charles had secured several major contracts related to the upcoming Lewis and Clark exposition, positioning his company for unprecedented profits.

The family’s public appearances increased dramatically that year with Catherine hosting fundraising events and Charles speaking at business conventions throughout the Pacific Northwest.

The timing of the photograph, September 1904, coincided with the peak of these public activities.

Morrison discovered society page mentions of the Whitmore children attending various social functions throughout that summer.

Dorothy and Helen were described as charming young ladies, while Thomas was noted for his quiet demeanor and serious disposition.

One particular newspaper clipping from August 1904 caught Morrison’s attention.

The Portland Orgonian Society reporter had written, “Young Thomas Whitmore, son of timber magnate Charles Whitmore, appeared notably withdrawn at yesterday’s charity picnic.

” While his sisters delighted attendees with their spirited participation in games, the lad remained close to his governness throughout the afternoon.

This observation aligned with Thomas’s expression in the photograph.

Something was clearly troubling the boy during what should have been the happiest period of his family’s rise to prominence.

Morrison realized that understanding Thomas’ situation required looking beyond the family’s public success to discover what shadows lurked within their private world.

Morrison’s next step led him to the Portland Academy, an exclusive private school that served the city’s wealthy families in the early 1900s.

The institution’s archives, housed in the basement of what was now Lincoln High School, contained detailed records of students from the era, including the Whitmore children.

The school’s enrollment records confirmed that Dorothy, Thomas, and Helen Whitmore had all attended Portland Academy.

However, Thomas’s academic file revealed a troubling pattern.

His grades, which had been excellent during his first two years, showed a dramatic decline, beginning in early 1904.

More concerning were the disciplinary reports filed by various teachers.

Thomas has become increasingly withdrawn and defiant, wrote his mathematics instructor in March 1904.

His attention wanders constantly, and he often appears to have not slept well.

When questioned about assignments, he becomes defensive and occasionally hostile.

His English teacher’s notes were even more alarming.

The boy’s essays have taken a dark turn.

Recent compositions about family life contain disturbing themes of imprisonment and escape.

I have requested a meeting with his parents to discuss these concerning developments.

Morrison discovered that no such meeting had taken place.

According to the school’s correspondence files, Charles Whitmore had responded to the teachers concerns with a Kurt letter stating that Thomas was experiencing temporary difficulties adjusting to increased family responsibilities and requesting that the school exercise patience during this transitional period.

The headm’s personal files contained a more detailed assessment.

Dr.

Edwin Hartwell had noted in June 1904, “Youn Whitmore’s behavior has become increasingly erratic.

He arrives at school appearing exhausted and frequently bears minor injuries which he attributes to accidents.

His sisters seem unaware of his distress, suggesting the family dynamics are more complex than they appear publicly.

Most intriguingly, Morrison found evidence that Thomas had attempted to confide in someone at the school.

A note in the files indicated that he had sought out the school’s groundskeeper, an elderly man named Patrick Ali, during lunch periods.

Ali, who had worked at the academy for over 20 years, was known for his kindness to troubled students.

Unfortunately, Ali’s own records were sparse.

The only relevant notation was found in Dr.

Hartwell’s journal.

Ali expressed concern about young Whitmore’s situation at home.

Claims the boy has made disturbing statements about his father’s expectations.

I have decided against pursuing this matter further given the family’s prominent position in our community.

This entry revealed a troubling pattern of institutional silence.

Even when school officials recognized Thomas’ distress, the Whitmore family social and economic influence had effectively protected them from scrutiny.

The photograph now seemed to capture not just a boy sadness, but his isolation within a system that prioritized reputation over his well-being.

Morrison realized that Thomas’ story reflected broader issues of child welfare in early 1900s Portland, where wealthy families operated with virtual impunity behind closed doors.

Morrison’s investigation took an unexpected turn when he discovered a reference to the Whitmore household staff in the Portland City Archives immigration records.

Among the family servants was Mario Sullivan, an Irish immigrant who had worked as the children’s governness from 1902 to 1905.

Through meticulous genealological research, Morrison located Mary’s great-g grandanddaughter.

Patricia Sullivan Hayes living in nearby Beaverton.

At 84 years old, Patricia had inherited not only her great-g grandandmother’s Irish accent, but also her collection of personal letters and journals.

a great grandmother.

Mary never spoke much about her time with wealthy families, Patricia explained as they sat in her modest living room, but she kept detailed journals, and she mentioned the Whitmore children frequently, especially the boy.

The journals written in Mary’s careful script provided an intimate glimpse into the Whitmore household that contrasted sharply with the family’s public image.

Mary’s entries from 1904 painted a picture of a home where appearances mattered more than the children’s emotional well-being.

An entry from July 1904 was particularly revealing.

Poor young Thomas grows thinner each week.

Master Charles has increased his character building exercises, requiring the boy to spend hours in the basement practicing discipline and obedience.

The child emerges from these sessions pale and shaking, but dare not speak of what transpires below.

Mary’s observations about Charles Whitmore were increasingly critical as 1904 progressed.

She described him as a man obsessed with control and reputation who viewed his children not as individuals but as extensions of his business empire.

Thomas as the only son and heir bore the brunt of his father’s expectations and frustrations.

Master Charles speaks of preparing Thomas for the responsibilities of manhood.

Mary wrote in August 1904, “Yet his methods are harsh beyond reason.

The boy has developed a stutter and frequently wakes screaming from nightmares.

When I suggested he might benefit from a physician’s care, the master accused me of feminine weakness and threatened my position.

The most disturbing entries concerned the period immediately before the family photograph was taken.

Mary wrote, “Master Charles announced that the family would have formal portraits made to commemorate their success.

” Thomas begged to be excused from the session, claiming he was ill, but his father would hear none of it.

“You will smile and represent this family with pride,” he commanded.

“Or face consequences worse than you can imagine.

” Mary’s final entry about the photograph session was brief but haunting.

The boy did his best to smile for the camera, but anyone with eyes could see the terror behind his expression.

I fear what Master Charles might do if the photographs do not meet his expectations of family perfection.

These revelations transform Morrison’s understanding of the photograph entirely.

Thomas’s forced smile and frightened eyes now made terrible sense.

He was a child trapped in an abusive situation, compelled to perform happiness while enduring private torment.

Armed with Mario Sullivan’s revelations, Morrison began searching for medical records that might shed light on Thomas’s condition.

Portland’s medical community in 1904 was small and interconnected.

With most wealthy families using the same handful of physicians, Dr.

James Whitman had been Portland’s most prominent pediatric physician during the early 1900s, serving families throughout the city’s elite neighborhoods.

His practice records donated to Oregon Health and Science University’s historical collection contained detailed notes about his young patients, including the Whitmore children.

The files revealed that while Dorothy and Helen received routine checkups and treatment for typical childhood ailments, Thomas’ medical history told a different story.

Beginning in early 1904, Dr.

Whitman had documented a series of concerning symptoms and injuries.

March 12th, 1904.

Thomas Whitmore presents with chronic fatigue, recurring nightmares, and what appear to be stress related stomach ailments.

Dr.

Whitman had noted a mother attributes symptoms to growing pains, but child exhibits signs of severe anxiety, multiple bruises on torso, explained as rough play by father.

Dr.

Whitman’s notes grew increasingly detailed and concerned throughout the year.

He documented Thomas’ dramatic weight loss, persistent insomnia, and developing speech impediment.

More troubling were his observations about the family dynamics during medical visits.

April 20th, 1904.

Child becomes visibly agitated when father enters examination room.

Thomas was beginning to describe games father plays with him when Mr.

Whitmore interrupted, stating such details were irrelevant to medical care.

Strongly suspect emotional trauma, but family’s influence makes direct intervention inadvisable.

The physician’s dilemma reflected the broader social constraints of the era.

Even medical professionals hesitated to challenge wealthy families, particularly on matters involving child welfare.

Dr.

Whitman’s notes revealed his growing frustration with his inability to help Thomas despite recognizing clear signs of abuse, a particularly disturbing entry from August 1904 documented Thomas’ condition just weeks before the photograph was taken.

Boy presents with fresh injuries to back and shoulders.

Father claims child fell from horse, but pattern and severity of wounds inconsistent with riding accident.

Thomas remains silent throughout examination, avoiding eye contact.

Fear for this child’s safety continues to grow.

Dr.

Whitman had attempted subtle intervention by recommending that Thomas spend time away from home, suggesting a visit to relatives or enrollment in a boarding school for his health.

Charles Whitmore had rejected these suggestions outright, stating that his son needed to learn discipline at home under proper supervision.

The final medical note about Thomas, dated September 10th, 1904, just 5 days before the photograph was taken, was brief but chilling.

Child appears to have resigned himself to his circumstances.

Previous agitation replaced by disturbing calm.

This emotional withdrawal may indicate severe psychological damage.

Have exhausted all diplomatically possible interventions.

Dr.

Whitman’s files contained one additional document that stunned Morrison, a letter the physician had drafted, but never sent to Portland’s child welfare authorities, describing his concerns about Thomas’ situation and requesting an investigation into the Whitmore household.

Morrison’s investigation led him to examine property records from the Whitmore’s Knob Hill neighborhood, hoping to identify families who might have witnessed or known about Thomas’ situation.

The Whitmore mansion had been surrounded by equally grand homes belonging to Portland’s other wealthy families, creating a tight-knit community of social elites.

Through genealological research, Morrison located descendants of the Hartwell family, who had lived in the mansion directly adjacent to the Whit Morris.

Elellanar Hartwell Morrison, no relation to Dr.

Morrison, now 91 and residing in a Portland assisted living facility, had vivid memories of her childhood neighbors.

Oh, I remember the Whitmore children very well, Elellanar said, her eyes brightening with recognition when shown the photograph.

Dorothy and Helen were delightful girls.

We often played together in our gardens.

But Thomas, she paused, studying the boy’s face in the image.

That poor child.

We children all knew something was terribly wrong next door.

Ellaner’s memories provided a child’s perspective on the Whitmore household that adult witnesses had been reluctant to discuss.

from her bedroom window.

She had often observed activities in the Whitmore backyard and could hear sounds from their house during quiet evenings.

Thomas was frequently in their garden very early in the morning or late at night, she recalled.

The mother thought it odd that a young boy would be outside at such hours.

Sometimes we could hear him crying, and occasionally there would be shouting.

Always Mr.

Whitmore’s voice, never the children’s.

The most disturbing of Ellanar’s memories involved the basement of the Whitmore mansion.

Her bedroom window provided a partial view of the basement’s small barred windows, and um she had noticed unusual activities there.

There were often lights in that basement late into the night, Elanar explained.

Father once mentioned to mother that he’d heard disciplinary sessions taking place there, but they agreed it wasn’t their place to interfere with another family’s child rearing methods.

That was how people thought in those days.

Elellanor remembered one particularly traumatic incident from the summer of 1904.

She had been awakened by sounds of distress from the Whitmore house and had seen Thomas standing at his bedroom window, pressing his hands against the glass as if trapped.

“He was looking directly at our house,” she recalled, tears forming in her eyes.

“I was only 8 years old, but I recognized the look of someone asking for help.

I tried to wake my parents, but by the time mother came to my room, Thomas was gone from the window.

Her family’s response to that incident was typical of the era’s social constraints.

Her father, Dr.

Edwin Hartwell had recognized Thomas’s distress, but felt powerless to act against such a prominent family without concrete evidence of wrongdoing.

Ellaner’s testimony confirmed what Morrison had suspected.

Thomas’ suffering had been visible to those around him, but social conventions and the Whitmore family’s influence had prevented intervention.

The photograph captured not just a boy’s private anguish, but a community’s collective failure to protect a vulnerable child.

Looking at this photograph now, Ellanar said sadly, I can see everything we should have recognized then.

That smile isn’t happiness.

It’s a plea for help that none of us answered.

Morrison’s research into Thomas’ fate led him through Portland’s vital records and newspaper archives, searching for information about what happened after the photograph was taken.

What he discovered was both heartbreaking and tragically predictable.

On November 18th, 1904, just two months after the family portrait session, the Portland Oregonian carried a brief obituary.

Thomas Whitmore, 12, beloved son of timber merchant Charles Whitmore and wife Katherine, died Tuesday following a brief illness.

Services will be held privately.

The family requests snow flowers or condolences during this difficult time.

The official death certificate filed with Multma County listed the cause of death as pneumonia complicated by nervous exhaustion.

Dr.

James Wittmann had signed the certificate, but Morrison noticed something unusual.

The physician had made several corrections to the document, and his normally precise handwriting appeared unsteady.

Further investigation revealed that Thomas’s death had occurred under suspicious circumstances that several people had questioned privately, though no formal investigation was ever conducted.

Mario Sullivan’s journal entries from that period provided the most detailed account of Thomas’s final weeks.

The boy’s condition worsened dramatically after the photographs were taken, Mary wrote.

Master Charles was displeased with Thomas’s appearance in the portraits and increased his corrective measures.

Thomas began refusing food and barely spoke, even to his sisters.

I begged Mistress Catherine to intervene, but she claimed Thomas was merely going through a difficult phase.

Mary’s final entries about Thomas were devastating.

November 15th, 1904.

Found Thomas collapsed in his room this morning.

He was burning with fever, but kept repeating, “I can’t do it anymore, Mary.

I just can’t.

” Dr.

Whitman was summoned, but seemed more concerned with speaking privately to Master Charles than examining the child.

November 17th, 1904.

Thomas passed peacefully in his sleep.

Dr.

Whitman says his heart simply gave out from the fever.

But I believe the boy’s spirit was broken long before illness claimed him.

Master Charles showed no grief, only concern about how the death might affect business relationships.

The governness’s account suggested that Thomas had essentially died of despair.

His physical illness, merely the final manifestation of months of psychological trauma.

Dr.

Whitman’s medical notes from that period, while diplomatically worded, supported this interpretation.

Child’s immune system appears compromised by chronic stress, the physician had noted.

Physical symptoms secondary to severe emotional disturbance fear that intervention came too late to prevent systemic collapse.

Morrison discovered that several people had questioned the official explanation for Thomas’s death.

The school groundskeeper, Patrick Omali, had reportedly told colleagues that the boy died of a broken spirit, not pneumonia.

Dr.

Whitman himself had confided to a colleague that Thomas’s death represented a failure of our entire community to protect an innocent child.

However, the Whitmore family’s influence ensured that no formal investigation was conducted.

Charles Whitmore’s business continued to prosper, and the family maintained their social standing.

Dorothy and Helen grew up never knowing the full extent of their brother’s suffering.

As the adults around them maintained a conspiracy of silence about Thomas’s true cause of death, as Morrison compiled his research, he realized that Thomas Whitmore’s story was not an isolated tragedy, but part of a broader pattern of child abuse that was systematically ignored in early 1900s Portland’s wealthy circles.

The historian discovered evidence of at least six other cases involving prominent families where children had suffered similar fates.

The Portland Children’s Aid Society, established in 1905, just months after Thomas’s death, had been founded partly in response to growing concerns about child welfare among the city’s elite families.

Morrison found correspondence between Dr.

Whitman and the society’s founders that revealed the physicians determination to prevent other tragedies like Thomas’.

We can no longer allow social position and economic influence to shield families from scrutiny when children’s lives are at stake.

Dr.

Dr.

Whitman had written to social reformer Margaret Evans in December 1904.

The death of young Thomas Whitmore must serve as a catalyst for change, ensuring that no other child suffers in silence behind the facade of respectability.

Morrison’s investigation revealed that several individuals who had witnessed Thomas’ suffering dedicated their later lives to child welfare reform.

Mario Sullivan, the family governness, had left domestic service entirely after Thomas’s death and became involved with early childhood protection organizations.

She spent the remainder of her career advocating for legal protections that would allow servants and teachers to report suspected abuse without fear of retaliation.

Dr.

Whitman had pushed for legislation requiring mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse by medical professionals, though such laws wouldn’t be enacted in Oregon until decades later.

His private papers contained detailed proposals for child protection measures that were remarkably progressive for the era.

Even Elellanar Hartwell, the neighbor child who had witnessed Thomas’ distress, had been profoundly affected by the experience.

As an adult, she became one of Portland’s most prominent advocates for children’s rights, serving on the boards of multiple child welfare organizations and frequently speaking about the importance of community responsibility in protecting vulnerable children.

Morrison discovered that the 1904 photograph had actually played a role in these reform efforts.

Dr.

Dr.

Whitman had kept a copy of the image and occasionally showed it to colleagues and lawmakers as evidence of how children’s distress could be hidden behind forced smiles and family respectability.

He called it a portrait of institutional failure, a reminder that society’s obligation to protect children transcended social and economic boundaries.

The photograph had become an informal symbol within Portland’s early child welfare movement, representing the hidden suffering of children whose voices had been systematically silenced by adult priorities and social conventions.

Several reformers kept copies of the image in their offices as motivation for their advocacy work.

Morrison realized that while Thomas’ story was tragic, it had ultimately contributed to meaningful social change.

The boy’s death had galvanized a community to confront uncomfortable truths about child welfare and to develop systems that might prevent similar tragedies in the future.

Morrison realized that while Thomas’ story was tragic, it had ultimately contributed to meaningful social change, the boy’s death had galvanized a community to confront uncomfortable truths about child welfare and to develop systems that might prevent similar tragedies in the future.

Dr.

Morrison’s investigation concluded with a profound understanding of how a single photograph could preserve not just an image but an entire story of human suffering, community failure, and eventual redemption.

The 1904 studio portrait of the Whitmore children had become far more than a family keepsake.

It was a historical document that revealed the hidden costs of social privilege and the importance of protecting vulnerable children.

In presenting his findings to the Portland Historical Society, Morrison emphasized how Thomas’s forced smile had served as a silent testimony to experiences that the boy himself could never have safely articulated.

The photograph captured a moment when a 12-year-old child was compelled to perform happiness while enduring private torment, creating a visual record of abuse that had been invisible to his community.

“This image teaches us to look beyond surface appearances,” Morrison explained to the gathered historians and social workers.

Thomas’s smile appears joyful until we examine his eyes, which tell a completely different story.

It reminds us that children in distress may be hiding in plain sight, their suffering masked by social expectations and family reputations.

The photograph had acquired new significance as evidence of how institutions, schools, medical practices, neighborhood communities, and even photography studios had collectively failed to protect a child whose distress was visible to anyone willing to look closely.

Yet it also demonstrated how individual witnesses from the governness Mario Sullivan to Dr.

Whitman to neighbor Ellaner Hartwell had been profoundly affected by their inability to help Thomas and had channeled their grief into lifelong advocacy for children’s rights.

Morrison’s research revealed that copies of the photograph had been quietly circulated among Portland’s early childy welfare advocates as a reminder of their mission.

The image had appeared in several early publications about child protection, always with Thomas’s eyes carefully, highlighted to demonstrate how children’s distress could be detected by observant adults.

The Portland Children’s Aid Society had used the photograph in training materials for teachers, medical professionals, and social workers, teaching them to recognize signs of abuse that might be hidden behind forced smiles and family respectability.

The image became a powerful tool for education and advocacy, helping prevent other children from suffering Thomas’ fate.

In the decades following Thomas’s death, Oregon had developed some of the nation’s most progressive child protection laws, many directly influenced by reformers who had been motivated by his story.

The state’s mandatory reporting requirements, established in the 1920s, were among the first in the country to legally protect professionals who reported suspected child abuse.

Morrison discovered that the photographs influence had extended far beyond Portland.

Dr.

Whitman had shared the image with colleagues at medical conferences across the Pacific Northwest, using it to demonstrate the importance of looking beyond physical symptoms to recognize psychological trauma in children.

The photograph had appeared in early pediatric textbooks as an example of how chronic stress could manifest in a child’s facial expressions and body language.

Perhaps most remarkably, Morrison found evidence that the photograph had influenced early developments in what would eventually become the field of child psychology.

Several prominent researchers had cited Thomas’ case and the visual documentation of his distress as evidence for the need to understand children’s emotional experiences rather than simply focusing on their behavior and academic performance.

The image had also played a role in changing photography practices.

Henrik Hoffman and other studio photographers had begun documenting their observations about concerning family dynamics, sometimes quietly alerting authorities when they suspected children were being mistreated.

The profession had developed informal networks for protecting vulnerable children who came through their studios.

As Morrison completed his research, he realized that the photograph’s most powerful legacy was its demonstration that historical images could serve as windows into experiences that had been systematically silenced.

Thomas’ story showed how careful historical investigation could give voice to those who had been unable to speak for themselves during their lifetimes.

The photograph now resides in the Portland Historical Society’s permanent collection, displayed alongside Morrison’s research and the testimonies of those who had known Thomas.

Visitors often spend long moments studying the boy’s face, learning to see beyond his forced smile to recognize the pain in his eyes.

The exhibit includes information about modern child protection resources, connecting Thomas’s historical tragedy to contemporary efforts to safeguard vulnerable children.

Morrison’s final report concluded with a reflection on the photograph’s enduring significance.

This image reminds us that every child’s suffering matters regardless of their family’s social standing or economic power.

Thomas Whitmore’s story teaches us that true protection of children requires courage from entire communities.

The willingness to see uncomfortable truths and act on them, even when doing so challenges powerful interests.

The 1904 studio photograph continues to serve as both a memorial to Thomas Whitmore and a call to action for anyone who encounters children in distress.

His smile, which appeared joyful to casual observers, now stands as a powerful reminder that the most vulnerable among us may be hiding their pain behind expressions of forced happiness, waiting for someone with the wisdom and courage to look more closely in the determination to

News

Archaeologists Just Discovered Something Beneath Jesus’ Tomb In Jerusalem… And It’s Bad

In Jerusalem, where history is layered as densely as the stone beneath its streets, a recent discovery has reopened questions…

Pope Leo XIV Declares The Antichrist Has Already Spoken From Within the Holy City A statement attributed to Pope Leo XIV has sent shockwaves through religious circles after reports claimed he warned that a deceptive voice had already emerged from within the Holy City itself. Was this meant as a literal declaration, a symbolic admonition, or a theological reflection on MORAL DECEPTION and SPIRITUAL AUTHORITY in modern times? As theologians dissect the language and believers debate its meaning, questions are rising about PROPHECY, INTERPRETATION, and WHY SUCH WORDS WOULD BE SPOKEN NOW.

With official clarifications limited and reactions intensifying, the message has ignited one of the most unsettling conversations the Church has faced in years.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Examine What Was Said—and How Different Voices Are Interpreting It.

In the quiet hours before dawn on January third, a sequence of events began inside the Vatican that would soon…

Pope Leo XIV Bans Popular Marian Devotion and Bishops Around the World React in Fury Reports circulating across Church networks claim Pope Leo XIV has restricted or banned a Marian devotion practiced widely in multiple regions—a move that allegedly triggered sharp backlash from bishops and clergy worldwide. What exactly was limited, why was the devotion targeted, and does this represent doctrinal clarification or disciplinary overreach? As statements and reactions pour in, divisions are emerging over TRADITION, AUTHORITY, and THE LIMITS OF PAPAL POWER.

With official explanations still unfolding and emotions running high, the controversy is quickly becoming a defining test of unity within the global Church.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Explore What’s Being Said—and Why the Reaction Has Been So Intense.

The marble floors of the papal residence reflected pale moonlight in the early hours before dawn. Pope Leo the Fourteenth…

Pope Leo XIV Ousts Influential Cardinals—Unveils Decades of Vatican Corruption Sources close to Vatican observers claim a dramatic internal shake-up followed decisions attributed to Pope Leo XIV—moves that allegedly sidelined several influential cardinals while reopening scrutiny into long-buried financial and administrative practices. What actions were actually taken, which allegations are supported by documentation, and how far back do the claims of misconduct reach? As senior officials rush to control the narrative, the moment has reignited debate over TRANSPARENCY, REFORM, and WHETHER THE CHURCH IS ENTERING A RECKONING LONG DELAYED.

With statements carefully worded and details emerging slowly, speculation continues to grow about how deep this crisis may run.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Examine What’s Being Reported—and What Remains Unconfirmed.

Pope Leo XIV Initiates Unprecedented Vatican Financial Reckoning Amid Internal Resistance In the early hours of the morning, when Vatican…

Pope Leo XIV Issues 12 New Rules for Mass—Catholics Struggle to Accept Sudden Liturgical Reform Reports circulating within Church circles claim Pope Leo XIV has introduced a set of 12 new guidelines affecting how Mass is celebrated—a move that has reportedly caught many clergy and lay Catholics off guard. What do these proposed changes involve, why were they introduced so abruptly, and how do they interact with long-standing liturgical traditions? As parishes react with confusion, concern, and cautious support, the discussion has quickly expanded to questions of AUTHORITY, CONTINUITY, and HOW MUCH CHANGE THE FAITHFUL CAN ABSORB AT ONCE.

With official explanations still unfolding, the reforms are already igniting one of the most intense liturgical debates in recent memory.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Explore the Rules Being Discussed—and Why Reactions Are So Divided.

Pope Leo I XIV Prepares to Reshape Catholic Worship as Vatican Debates Historic Liturgical Reform The final light of a…

Pope Leo XIV Shatters Vatican Financial Secrecy Pillar — Cardinals Scramble to Contain Fallout According to reports circulating among Vatican analysts, Pope Leo XIV has taken a dramatic step that may have dismantled a long-standing pillar of financial secrecy within the Holy See. Sources suggest the move triggered urgent meetings and behind-the-scenes efforts by senior cardinals to manage potential repercussions.

What exactly was revealed or restructured, why was this moment chosen, and how deep could the consequences run for Church governance and global trust? As officials issue carefully worded statements, questions intensify around TRANSPARENCY, ACCOUNTABILITY, and WHETHER THIS SIGNALS A NEW ERA—or a deepening internal rift.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Examine What Changed—and Why the Fallout Is Spreading Fast.

Secret Vatican Decree Triggers Internal Crisis and Redefines the Future of Church Governance In the early hours before dawn, within…

End of content

No more pages to load