Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of North Carolina.

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you are watching from and the exact time at which you are listening to this narration.

We are interested in knowing to which places and at what times of day or night these documented stories reach.

In the autumn of 1912, when the maple trees surrounding Caldwell County turned crimson and gold, the residents of the small township of Whitaker’s Mill spoke only in hush tones about what had transpired at the Witford estate.

It wasn’t the kind of story that made newspaper headlines.

Rather, it was the kind that traveled through whispers, fragmenting and transforming with each telling, until the truth became nearly impossible to discern from fiction.

The case files, bound in leather and stored in the county records office, were cataloged simply as incident report, Witford property, October 1912.

What those yellowing pages contained would remain largely unknown to the public for nearly a decade.

The Witford mansion stood three miles from the nearest neighbor, positioned a top a gentle rise that allowed it to overlook the valley and the winding Kataba River below.

Built in 1874 by Thomas Witford, a textile magnade who had accumulated his fortune during the reconstruction era, the house was an architectural marvel of its time.

three stories of imposing red brick with a distinctive octagonal tower on its eastern facade.

Local lore suggested that Thomas had designed the tower himself, insisting that its windows be positioned to capture both the sunrise and the sunset, depending on the season.

By 1912, the estate had passed to Thomas’s son, Everett Witford, a man described in county records as of distinguished bearing and reserved temperament.

Everett had expanded the family business significantly, investing in railroads and timber rights throughout the Blue Ridge foothills.

A ledger discovered in the county clerk’s office dated 1899 showed that the Witford holdings encompassed over 2,000 acres of prime woodland and several miles of railway.

What made the Witfords unusual in Caldwell County was not merely their wealth, but their peculiar insularity.

Unlike other prominent families who engaged in local politics and social affairs, the Witfords rarely ventured into Whitaker’s mill.

When they did, it was only Everett who appeared, conducting business with a brisk efficiency before returning to the estate.

His wife, Eleanor, was seldom seen in public after their marriage in 1895, and many of the younger residents of the county claimed never to have laid eyes on her at all.

The couple had three children, twins Robert and Richard, born in 1896, and a daughter, Maryanne, born in 1900.

A notation in the county birth registry indicated that Eleanor had suffered significant complications during Maryanne’s birth, requiring the attendance of a specialist physician brought in from Charlotte.

Some speculated that these complications explained her subsequent reclusiveness.

According to tax records and business ledgers preserved in the local historical society’s collection, the Witford fortune grew substantially between 1900 and 1912.

The textile mill expanded to employ over 100 workers.

The timber operation shipped lumber as far north as Boston, and the railroad connections ensured the family’s goods moved efficiently to market.

On paper, the Witfords represented the epitome of southern industrial success.

Yet, testimonies collected years later from former household staff painted a different portrait of life within the mansion’s brick walls.

Martha Coleman, who served as a kitchen maid from 195 until 1910, described the household atmosphere as heavy with unspoken rules.

In an interview given to a historical society volunteer in 1918, Coleman recalled, “The children took their meals separately from Mr.

and Mrs.

Whitford.

They were to be neither seen nor heard when their father was home, which thankfully wasn’t often, as his business took him away for weeks at a time.

” Coleman’s account, preserved on a series of handwritten notes, described an unusual household arrangement wherein the east wing of the mansion, including the octagonal tower, remained locked and inaccessible to staff.

Only Mr.

Witford had the key, she stated.

Not even Mrs.

Whitford was permitted entry, at least not that any of us ever witnessed.

The autumn of 1912 began unremarkably for Caldwell County.

The harvest had been bountiful.

The textile mill was operating at full capacity and the timber operations were preparing for the winter season when transportation would become more difficult on the mountain roads.

In late September, according to business correspondents preserved in the company archives, Everett Witford departed for Richmond, Virginia to negotiate a new contract for cotton processing equipment.

He was expected to return on October 3rd.

He did not.

A telegram delivered to the estate on October 4th expressed regrets from the equipment manufacturer that Mr.

Witford had failed to appear for their scheduled meeting.

This information comes from Harold Jenkins, who served as the Witford business manager and who in 1920 provided a sworn statement to county officials investigating the events that followed.

According to Jenkins, Elellanar Witford displayed no immediate concern upon receiving news of her husband’s absence.

She merely nodded and instructed me to telegraph our Richmond office to inquire whether Mr.

Witford had perhaps redirected his itinerary.

Jenkins stated it was not unusual for him to extend his business trips without prior notice to the household.

The Richmond office reported no contact with Witford.

Similar inquiries to hotels and other business associates yielded no information regarding his whereabouts.

It wasn’t until October 8th, 5 days after his expected return, that Elellanar Witford reportedly requested that the local sheriff be notified of her husband’s disappearance.

Sheriff Thomas Blackwood’s initial investigation was peruncter, according to his own records.

Mr.

Witford is a man of business and means, he wrote in his report dated October 10th.

It is not uncommon for gentlemen of his standing to alter their plans without immediate notification to all parties.

Nevertheless, telegrams were dispatched to authorities in Virginia and neighboring states requesting information.

On October 12th, a development occurred that shifted the tenor of the investigation.

A porter at the Richmond Train Station came forward with information that he had indeed seen Everett Witford board the southbound train to Charlotte on the evening of October 2nd as originally planned.

This meant that Witford had departed Richmond, but never arrived at his destination.

The railway company conducted a search along the route, but found no evidence of accident or foul play.

Passengers who had traveled on the same train were interviewed with several confirming that they recalled seeing a gentleman matching Witford’s description disembark at the Charlotte station.

From there the trail went cold.

It was at this point, according to Sheriff Blackwood’s increasingly detailed reports, that attention began to turn toward the Witford estate itself.

if Everett had indeed returned to Charlotte had he perhaps made his way home, only to meet with Misfortune upon arrival.

On October 15th, Sheriff Blackwood and two deputies conducted the first of what would become a series of interviews with the Witford household.

Eleanor received them in the mansion’s front parlor, dressed in a somber blue dress that, according to Blackwood’s notes, gave her the appearance of already being in mourning.

Also present were the three Whitford children, the twins then 16 years of age, and Maryanne, 12.

Deputy Samuel Hawkins later remarked that what struck him most about the interview was not what was said, but rather the peculiar dynamics within the family.

The boys stood behind their mother’s chair, one on each side, like centuries, he recalled in 1919.

They spoke only when directly addressed, and even then their responses were identical in both content and timing, as if rehearsed.

The daughter said nothing at all, but watched everything with unusual intensity.

Elellanar Witford maintained that she had no knowledge of her husband’s whereabouts.

She stated that on the night of his expected return, she had retired early with a headache.

The household staff had been instructed to alert her upon Mr.

Witford’s arrival, but no such alert had come.

When she awoke the following morning, his absence was noted, but not yet considered alarming.

When Sheriff Blackwood requested permission to search the grounds and outuildings, Ellaner consented without hesitation.

“You may look wherever you wish,” she reportedly stated, though I cannot imagine what you expect to find.

The initial search revealed nothing unusual.

The stables, carriage house, and groundskeepers cottage were examined, as were the gardens and the small family cemetery where previous generations of Witfords were interred.

No sign of disturbance was noted, and no evidence suggesting Everett Witford’s return was discovered.

It was only when Blackwood requested access to all rooms within the mansion itself that he encountered resistance.

Elellanar informed him that certain areas of the house, specifically the east wing, including the octagonal tower, remained locked at her husband’s insistence, and she possessed no key.

Those rooms contain Mr.

Witford’s private business papers and personal collections, she explained, according to the sheriff’s report.

He has always been most insistent about their security.

I have respected his wishes in this matter throughout our marriage.

Blackwood, lacking sufficient cause to force the issue, noted this restriction in his report, but did not press further at that time.

He concluded the day’s investigation with a promise to return if new information emerged.

New information did indeed emerge, though not from any expected source.

On the morning of October 19th, a local fisherman named Joseph Miller made a discovery along the banks of the Kataba River, approximately one mile downstream from the Witford property.

What he found, partially concealed among river rocks and autumn leaves, was a man’s leather wallet containing business cards identifying its owner as Everett Witford.

The discovery of the wallet prompted a more thorough search of the riverbank and surrounding woods.

Sheriff Blackwood organized a party of 12 men who combed the area methodically over the course of two days.

No further personal effects were discovered, and most significantly, nobody was found.

The wallet itself presented a puzzle.

While weathered by exposure to the elements, it contained all items one would expect.

a small amount of currency, business cards, and a folded railway ticket stub showing travel from Richmond to Charlotte on October 2nd.

Nothing had been removed, ruling out robbery as a motive if foul play was involved.

Sheriff Blackwood returned to the Witford estate on October 21st with news of the discovery.

According to his report, Elellanar Witford received the information with composure that he found remarkable under the circumstances.

She confirmed that the wallet shown to her did indeed belong to her husband.

When asked if this altered her perspective on his disappearance, she reportedly replied, “It suggests only that he was near home when something occurred.

What that might have been, I cannot say.

” It was during the second visit to the estate that Deputy Hawkins observed something he found noteworthy.

While Sheriff Blackwood was speaking with Eleanor in the parlor, Hawkins glimpsed the Whitford daughter, Maryanne, standing at the top of the main staircase.

She was holding what appeared to be a ledger or large book, Hawkins later reported.

When she noticed my attention, she retreated immediately down the hallway toward the east wing.

This observation, seemingly minor at the time, would later take on greater significance.

As October drew to a close, the investigation into Everett Witford’s disappearance stalled.

No body had been recovered.

No witnesses had come forward with sightings after Charlotte, and no evidence suggested conclusively what had befallen him.

Sheriff Blackwood’s reports from this period reflect increasing frustration and a sense that critical information remained just beyond his reach.

On October 30th, an application was filed by Harold Jenkins on behalf of Elellanar Witford requesting that the business affairs of the absent Everett Witford be temporarily placed under her administration to prevent disruption to the operations of the textile mill and timber concerns.

The county judge granted this request, noting that while Mr.

Whitford’s death could not be confirmed.

His extended unexplained absence necessitated practical arrangements.

With this legal matter settled, a curious quiet fell over the case.

Sheriff Blackwood’s final report for the year, a dated December 12th, stated only that inquiries continue as opportunities arise and that the Witford family has been advised to alert the sheriff’s office immediately should any communication from the missing man be received.

For all practical purposes, the investigation into Everett Witford’s disappearance had reached an impass.

The man himself, whether dead or by choice, had vanished as completely as if he had never existed.

Yet in the quiet township of Whitaker’s mill, the whispers continued.

Something about the Witford case lingered in the collective consciousness, a splinter too deeply embedded to ignore.

Some spoke of light seen in the octagonal tower at odd hours, visible from the valley road on clear nights.

Others remarked on the increased privacy measures at the estate, higher fences installed around the perimeter, the dismissal of long-standing household staff, the children withdrawn from their private tutoring arrangements in favor of home education supervised by their mother.

The Witford family, always private, became virtually cloistered in the year that followed Everett’s disappearance.

The business operations continued under Elellaner’s surprisingly capable direction, but the human elements, the family behind the fortune, receded further from public view.

It would be nearly 10 years before the mysteries of the Witford estate would resurface in the public record, and when they did, the revelations would prove far more disturbing than a mere disappearance.

During those quiet years, as the world beyond Caldwell County experienced the upheavalss of the Great War, life at the Witford mansion continued behind its brick walls and wrought iron gates.

The twins, Robert and Richard, assumed responsibilities within the family businesses upon turning 18 in 1914.

Though unlike their father, they conducted affairs primarily through correspondence and intermediaries rather than personal appearances.

Maryanne Witford, according to school records that ended abruptly in 1913, had been a student of exceptional intelligence and unusual interest.

Her former tutor, Miss Katherine Harlo, noted in a letter to a colleague, discovered years later, among Miss Harllo’s personal effects, that the girl had an unsettling preoccupation with family history and financial matters far beyond her years, and that she asked questions about her father’s business dealings that no child could think to ask.

Elellanar Witford maintained control of the family enterprises with unexpected acumen.

Quarterly reports filed with the county clerk’s office showed that under her management, the textile operations expanded to include a second mill, while the timber business secured several lucrative contracts supplying materials for military purposes during the war years.

The Witford fortune, already substantial, grew exponentially between 1913 and 1919.

From all external appearances, the family had not merely survived the loss of its patriarch.

It had flourished.

But appearances, as the residents of Whitaker’s Mill would eventually learn, could be misleading.

And beneath the veneer of continued prosperity, something dark was taking root in the octagonal tower of the Witford mansion.

The year 1920 brought significant changes to Whitaker’s Mill.

Sheriff Thomas Blackwood retired after serving the county for 27 years, passing his badge to his former deputy Samuel Hawkins.

The textile industry faced new challenges as the post-war economy adjusted, though the Witford Mills continued to operate at near capacity.

And in February of that year, a fire at the county records office destroyed numerous documents dating back to the previous century, including, it was presumed, many of the original files pertaining to Everett Witford’s disappearance.

It was against this backdrop of transition that the second chapter of the Witford mystery began to unfold.

On April 7th, 1920, Harold Jenkins, who had continued to serve as business manager for the Whitford Enterprises, was found dead in his office at the mill.

According to the coroner’s report, Jenkins had suffered a sudden failure of the heart, not uncommon for a man of 62 years.

The death was deemed natural and a brief obituary in the local newspaper noted his years of service to the Witford family and his reputation as a meticulous recordkeeper.

What the obituary did not mention was that Jenkins had scheduled a meeting with the newly appointed Sheriff Hawkins for the following morning.

This detail emerged only later when Hawkins himself revealed it during subsequent investigations.

The nature of the intended meeting remained unspecified, but Hawkins would later testify that Jenkins had seemed uncharacteristically agitated when he had requested the appointment, insisting that it concerned a matter of grave importance regarding the Witford accounts.

Jenkins’s death might have remained an unremarkable event had it not been for the actions of his widow, Margaret.

While sorting through her late husband’s personal effects, she discovered a locked metal box containing a journal and several folded documents that Jenkins had apparently kept hidden behind a false panel in their bedroom wardrobe.

Recognizing the potentially sensitive nature of these materials, Margaret Jenkins did not immediately report her discovery.

Instead, according to her later statement, she spent several evenings reviewing the contents herself.

What she found disturbed her sufficiently that on April 20th, she requested a private meeting with Sheriff Hawkins.

The journal, which Hawkins would describe in his official report as meticulously maintained in Jenkins’s distinctive hand, contained entries dating back to 1912, beginning shortly after Everett Witford’s disappearance.

The earliest entries expressed Jenkins’s growing concerns about discrepancies he had discovered in the Witford business accounts.

Discrepancies that had begun to appear approximately 6 months before Everett vanished.

There are substantial sums being transferred to accounts unknown to me.

Jenkins had written in an entry dated October 25th, 1912.

When I brought this to EW’s attention in August, he assured me that these were legitimate business expenses related to expansion efforts.

Now, with his absence, I find myself unable to reconcile the figures.

Yet, Mrs.

W.

shows no concern when I raise the matter.

Subsequent entries documented Jenkins’s increasingly troubled observations of the Witford family dynamics following Everett’s disappearance.

He noted that Eleanor had taken possession of her husband’s private study, though not interestingly the locked rooms of the East Wing within days of the disappearance being reported.

He described the twins as eerily coordinated in their movements and speech, suggesting they operate less as individuals than as extensions of their mother’s will.

Most disturbing were his observations regarding Maryanne Witford.

The girl watches everything, he wrote in February 1913.

She appears at unexpected moments in the office, silent as a shadow, often with that ledger clutched to her chest.

When questioned about her presence, she merely states that she is learning the family business and that her mother has encouraged this education.

The journal entries grew more sporadic after 1915, as if Jenkins had become cautious about documenting his concerns.

Several pages appeared to have been torn out, creating gaps in the chronology.

The final entry, dated April 5th, 1920, just 2 days before his death, contained a single cryptic line.

I have found the original ledger, God help us all.

Accompanying the journal were several folded documents that proved to be unofficial copies of financial records, apparently made by Jenkins without the knowledge of the Witford family.

These showed a pattern of substantial funds totaling over $100,000 between 1911 and 1920 being directed to a series of numbered accounts at banks in Charlotte, Richmond, and as far away as New York City.

Sheriff Hawkins, recognizing the potential implications of these discoveries, proceeded with caution.

The Witford family remained the largest employer in the county, and allegations of financial impropriy could have devastating economic consequences for the region.

Moreover, while Jenkins’s records suggested unusual financial activities, they provided no clear evidence of criminal wrongdoing, nor did they shed any light on Everett Witford’s fate.

Nevertheless, Hawkins felt compelled to reopen the investigation into the disappearance.

He began discreetly reviewing what remained of the original case files and interviewing former household staff who had worked at the estate during the relevant period.

One such interview proved particularly illuminating.

Thomas Green, who had served as the Witford Gardener from 198 until 1914, provided an account that had not been included in the original investigation.

According to Green, on the night of October 3rd, 1912, the night Everett Witford was expected to return, he had been tending to a broken water pump near the kitchen gardens, when he observed unusual activity at the mansion.

It was past midnight, Green stated in his sworn testimony.

I saw lights moving in the east wing in rooms that had always been kept locked.

Then I heard what sounded like something heavy being dragged across the floor, followed by the distinct sound of the service elevator, the one used for moving furniture between floors.

Green admitted that he had not reported these observations at the time of the original investigation.

Mr.

Jenkins advised me against it, he explained.

He said that without clear evidence of wrongdoing, speaking about the family’s private matters could cost me my position.

Armed with this new testimony and Jenkins’s records, Hawkins determined that a more thorough examination of the Witford estate was warranted.

On May 3rd, 1920, he obtained a judicial order permitting a complete search of the property, including the previously inaccessible East Wing.

Elellanar Witford, now 47 years old, received news of the impending search with what Hawkins described as icy composure.

She did not object to the order, but requested 24 hours to prepare the family and household for this intrusion.

Given her apparent cooperation, Hawkins granted this reasonable delay.

It was a decision he would come to regret.

When Hawkins and his deputies arrived at the Witford estate on the morning of May 4th, they were met not by Ellaner, but by her sons, Robert and Richard, now 24 years old.

The twins informed the sheriff that their mother had been taken suddenly ill during the night and was confined to her bed under a physician’s care.

This is most unfortunate timing.

Robert or possibly Richard Hawkins noted in his report that he remained unable to distinguish between them.

stated.

However, we have been instructed to provide you with full access to the house, including the east wing, as required by your order.

The search began in the main sections of the house, which revealed nothing of particular note.

The mansion, while imposing and luxuriously appointed, showed signs of reduced maintenance compared to its former grandeur.

Several rooms appeared unused, their furniture covered with dust cloths.

It was when the search party reached the east wing that matters took a decidedly unusual turn.

The heavy oak door separating this section from the rest of the house was unlocked as promised.

But beyond it lay what Hawkins would later describe as a different world entirely, while the main portion of the mansion reflected the typical appointments of a wealthy southern home.

Oriental rugs, mahogany furniture, family portraits in guilt frames.

The east wing presented an environment of austere functionality.

The rooms contained plain wooden desks, filing cabinets, and walls lined with shelves holding leather-bound ledgers and document boxes.

There were no decorative elements, no comfortable furnishings, nothing to suggest these spaces were designed for anything but business.

Most puzzling was the complete absence of dust or disuse.

Unlike the neglected rooms elsewhere in the mansion, these spaces showed evidence of regular occupation and meticulous maintenance.

Fresh ink stains marked one desk plotter, a half-filled coffee cup sat on another.

The search party worked methodically through the wing, documenting the contents of each room.

The ledgers, when examined, proved to contain detailed financial records dating back to 1874, when Thomas Witford had first established the family businesses.

The level of detail was extraordinary.

Every transaction, no matter how minor, appeared to be recorded along with coded annotations that were not immediately decipherable.

It was in the octagonal tower occupying the uppermost floor of the east wing that the search yielded its most significant discovery.

This room, circular in layout with windows facing each direction, contained a single large desk positioned in the center.

Unlike the utilitarian furnishings in the other rooms, this desk was an ornate piece of craftsmanship carved from dark walnut with intricate designs decorating its edges and legs.

On the desk lay a single ledger bound in red leather that had cracked with age.

The book lay open as if someone had been reviewing it recently.

The page displayed columns of figures and cryptic notations unlike those in the other records.

Most striking was the heading at the top of the page.

Blood accounts October 1912.

Before Hawkins could examine the ledger more closely, the search was interrupted by a commotion from the main part of the house.

One of the deputies, who had remained near the entrance, called out that there was a fire in the west wing.

Smoke was already filling the hallway connecting the two sections of the mansion.

The search party was forced to evacuate immediately with Hawkins grabbing the red ledger before retreating.

By the time they reached the front drive, flames were visible through several ground floor windows.

The twins, who had ostensibly been accompanying the search party, but had separated from them just before the fire was discovered, now appeared from around the side of the house, their expressions unreadable.

“Our mother,” one of them stated.

“She is still upstairs.

” Despite the rapidly spreading fire, Hawkins and two deputies re-entered the mansion to attempt a rescue.

They managed to reach the second floor master bedroom only to find it empty.

There was no sign of Elellanar Witford, ill or otherwise.

The fire, which had begun in multiple locations throughout the West Wing, spread with alarming speed.

Within an hour, despite the efforts of hastily organized bucket brigades from the nearby mill, the main structure of the Witford mansion was engulfed.

By nightfall, only the brick exterior walls and the peculiar octagonal tower remained standing amidst the smoldering ruins.

No bodies were recovered from the site.

Elellanar Witford had vanished as completely as her husband had 8 years earlier.

The twins, when questioned, maintained that their mother had indeed been in her bedroom when the fire broke out, and they could offer no explanation for her absence from that location when rescuers arrived.

As for Maryanne Witford, her whereabouts during the fire remained a mystery.

The twins claimed that their sister had departed two days earlier for health treatments at a facility in the mountains, though they could provide neither the name nor the location of this establishment.

In the aftermath of the fire, Sheriff Hawkins secured the Red Ledger as evidence.

His examination of its contents, conducted with the assistance of a bank examiner from Charlotte, revealed a financial record unlike any they had encountered before.

The ledger documented not conventional business transactions, but rather what appeared to be a system of debts and payments linked to specific individuals, many of them prominent citizens from throughout the region.

Next to each name was a notation of blood value followed by a dollar amount.

Some entries included additional notations such as partial payment received or account settled in full.

Most disturbing were the entries marked harvested or collection complete, which were accompanied by dates, several of which corresponded with known disappearances or unexplained deaths in surrounding counties over the previous 40 years.

The ledger, which came to be known as the blood account book, dated back to 1874, the year Thomas Witford had established his fortune.

The earliest entries were in a different hand than the later ones, suggesting that the practice had begun with the family patriarch and continued through his son.

The final entry dated October 3rd, 1912, contained the name Everett Witford with the notation founders bloodline debt called due account transferred to EW the two by right of twin birth harvesting witnessed and certified.

Below this entry, in what appeared to be a feminine hand, was written, “The debt that feeds the fortune is paid in blood across generations.

” The implications of these records were so disturbing that Sheriff Hawkins initially hesitated to make them public.

Before proceeding further with the investigation, he consulted with state authorities and requested assistance from investigators with experience in complex financial crimes.

Meanwhile, the surviving Witford brothers wasted no time in consolidating their position.

Within days of the fire, they had relocated to the company offices in Charlotte.

From there, they issued statements expressing their profound grief over the tragic accident that had claimed their mother’s life and destroyed their ancestral home.

They announced plans to rebuild the mansion in due course, but indicated that for the foreseeable future they would manage the family enterprises from Charlotte.

The brothers also initiated legal proceedings to have their sister Maryanne declared incompetent due to mental infirmities of a hereditary nature.

According to court documents they filed, Maryanne had been suffering from delusions and nervous excitability for several years and required institutional care.

Their petition requested that they be appointed as her legal guardians and granted control over her portion of the family estate.

This legal maneuver might have succeeded had Maryanne herself not appeared at the court hearing on June 5th, 1920.

Now 20 years old, she presented herself with a composure and articulateness that directly contradicted her brother’s claims.

Moreover, she was accompanied by a distinguished physician from Baltimore, who testified that he had examined her and found no evidence whatsoever of mental deficiency or instability.

The court ruled in Maryanne’s favor, dismissing the brother’s petition.

In a further surprising development, Maryanne immediately filed a counter petition alleging that her brothers had conspired to defraud her of her inheritance through falsified business records.

She requested that an independent receiver be appointed to manage the Witford Enterprises until ownership could be properly determined.

The legal battles between the siblings would continue for months, generating volumes of court records that provided glimpses into the inner workings of both the family and its businesses.

These records, combined with the evidence from the blood account book and Jenkins’s journal, gradually revealed a pattern that extended back through two generations of the Witford family.

What emerged was the outline of a financial empire built upon a foundation of systematic predation.

Thomas Witford, it appeared, had initiated a practice of identifying vulnerable individuals or families in financial distress, offering them loans with initially favorable terms, then manipulating conditions to render repayment impossible.

When borrowers defaulted, the consequences went far beyond the usual seizure of property or assets.

The blood account book suggested that some form of physical harvesting occurred, though the precise nature of this process remained unclear from the records alone.

What was evident was that these harvests coincided with the disappearance or deaths of the individuals involved and that following such events, the Witford businesses invariably experienced periods of remarkable prosperity.

This pattern had continued under Everett Witford’s management with the disturbing addition that he had apparently expanded the practice to include individuals within his own social circle when external opportunities became insufficient.

The final terrible culmination appeared to be that Everett himself had somehow become subject to the same system harvested by his own family with the twins as beneficiaries and likely perpetrators.

Eleanor’s role in these events remained ambiguous.

Some entries in Jenkins’s journal suggested that she had been unaware of the full extent of the practice until after her husband’s disappearance, at which point she had been forced to become complicit to protect herself and her children.

Other evidence, particularly the handwriting in later portions of the blood account book, indicated that she may have taken an active role in continuing the system.

As for Maryanne, her position was perhaps the most complex of all.

Court testimony revealed that from a young age, she had shown an unusual interest in the family’s financial affairs, an interest that Everett had discouraged, but that Elellanor had later fostered.

The ledger that Deputy Hawkins had observed her carrying years earlier had likely been her own record of the family’s activities, compiled through careful observation and clandestine examination of her father’s papers.

Whether she had been a reluctant witness, an active participant, or perhaps something else entirely, a chronicler preserving evidence of the family’s crimes remained unclear.

What was certain was that by 1920 she had positioned herself in opposition to her brothers and was actively working to dismantle the system they had inherited.

The legal proceedings between the Witford siblings reached a crescendo in September 1920 when state authorities acting on evidence provided by Sheriff Hawkins and supplemented by Maryanne’s testimony executed search warrants at the Whitford Company offices in Charlotte.

What they discovered there further illuminated the dark practices that had sustained the family fortune for decades.

Hidden within a concealed vault behind the offic’s main safe were additional ledgers, correspondents, and most disturbingly small containers holding what appeared to be biological samples preserved in solution.

These containers were labeled with names that corresponded to entries in the blood account book accompanied by dates and notations regarding quality and yield.

Medical experts consulted by the investigators determined that the preserved samples were human tissue specifically extracted from major organs.

analysis indicated that the preservation methods were sophisticated for their time, suggesting specialized knowledge beyond that of an ordinary physician.

This discovery prompted authorities to re-examine several unexplained deaths and disappearances across the region dating back to the 1870s.

Exumations were ordered in cases where circumstantial evidence suggested a connection to the Witfords.

In multiple instances, autopsies revealed that the deceased had been subjected to precise surgical procedures resulting in the removal of specific organs or tissue.

Procedures that appeared to have been conducted while the victims were still living.

Investigators theorized that Thomas Whitford, who had briefly studied medicine before turning to business, had developed a perverse belief in the regenerative or strengthening properties of human tissue harvested from living subjects.

Documents recovered from the Charlotte office included personal journals kept by Thomas Witford that referenced experiments aimed at distilling the essence of vitality and transferring life force through blood and tissue.

While much of the writing was coded or deliberately obscure, the underlying premise appeared to be that by consuming or somehow incorporating tissue from carefully selected victims, one could extend life and vitality while simultaneously increasing financial prosperity.

This belief, possibly rooted in obscure European medical theories he had encountered during his education, had evolved into a systematic practice, whereby financial entrapment became the means of securing victims.

The most troubling aspect of these records was their suggestion that Thomas had systematically passed this knowledge and practice to his son, Everett, who had in turn begun training his twin sons in the same methods.

The journals indicated that the process required specific bloodline attributes in its practitioners, attributes that Thomas believed were strengthened through selective marriage and preserved most effectively in male twins.

This explained the family’s unusual insularity and Elellanar’s limited role in the business operations until after Everett’s disappearance.

It also shed light on the fate of Everett himself.

According to entries in the blood account book, Everett had acred his own blood debt through his years of practice, a debt that could only be settled through his own harvesting.

The notation suggesting the transfer of his account to EW2, likely referred to one or both of the twins, who had apparently conducted the harvesting of their own father as a form of grotesque inheritance ritual.

The twins, Robert and Richard Witford, were arrested on October 1st, 1920 at a hunting lodge in the mountains near Asheville.

They offered no resistance, but maintained absolute silence throughout the arrest procedure.

When separated for questioning, each brother responded with identical phrases and gestures, reinforcing the eerie synchronicity that others had observed throughout their lives.

The evidence against them appeared overwhelming.

financial records documenting their victim’s entrapment, the preserved tissue samples, the blood account book, and testimony from individuals who had witnessed unusual activities at both the Witford estate and various other properties owned by the family throughout the region.

Yet, the prosecution faced significant challenges.

The brother’s silence extended to legal proceedings where they refused to enter please or communicate with courtappointed counsel.

More problematic was the disappearance of key evidence following a break-in at the county sheriff’s office on October 12th.

Several ledgers, including the original blood account book, were stolen, along with many of the preserved tissue samples that had been held as evidence.

Sheriff Hawkins suspected the involvement of individuals who had benefited financially from association with the Whitford Enterprises, individuals who might themselves be implicated if the full extent of the family’s activities became public knowledge.

His investigation into the break-in led to several prominent citizens, but evidence sufficient for prosecution proved elusive.

Meanwhile, Maryanne Witford maintained a curious position throughout these proceedings.

While she provided testimony regarding the family’s business practices and her brother’s activities, she refused to discuss certain aspects of the case, particularly those related to her mother’s role and the specific nature of the harvesting process.

When pressed on these points during depositions, she would state only that some knowledge is too dangerous to preserve and that certain chapters of the family history must remain closed.

As the case against the twins proceeded haltingly through legal challenges and evidentiary issues, a new development occurred that would ultimately reshape the entire investigation.

On November 5th, 1920, Maryanne Witford disappeared from her Charlotte hotel room, leaving behind a single sealed envelope addressed to Sheriff Hawkins.

The letter contained within, which remains preserved in the state archives, read in part, “By the time you read this, I will have departed to conclude family business that cannot be entrusted to the courts.

” The Witford legacy extends beyond what has been discovered thus far, with connections to individuals whose names would shock the public conscience if revealed.

My brothers are merely the most recent practitioners of arts that should never have been revived from the dark centuries.

Our fortune was built on blood and sustained by ritual.

Each generation has paid its price, and mine shall be no exception.

I have learned what was hidden from me as a child, studied what was forbidden to women of our line, and now understand what must be done to break the cycle.

The family ledger contains more than financial accounts.

It binds us through blood mathematics that must be balanced.

When you read in tomorrow’s papers of a fire at the hunting property near Morgan’s Creek, know that the final accounting has been settled.

True to Maryanne’s prediction, the following morning brought news of a devastating fire at a remote Witford property.

The blaze, which witnesses described as burning with unusual intensity and colored flames, completely destroyed the hunting lodge and its outbuildings.

When fire crews were finally able to approach the ruins, they discovered three charred bodies within the main structure.

Dental records and personal effects identified two of the deceased as Robert and Richard Witford, who had apparently been removed from custody through means that were never satisfactorily explained.

The third body, burned beyond recognition, was presumed to be Maryanne Witford, though conclusive identification proved impossible.

Most mysterious of all was the discovery in the ashes of what had been the lodge’s root seller of a metal container holding the missing blood account book and several journals that had not previously been recovered.

These items, though damaged by heat, remained largely legible and contained additional entries not present when the book was initially discovered.

The final page bore a single line in what handwriting experts identified as Maryanne’s hand.

The bloodline ends.

The debt is paid.

The fire effectively concluded the active investigation into the Witford case.

With the presumed deaths of all remaining family members, there remained no one to prosecute.

The authorities, perhaps relieved to avoid a trial that would have exposed the complicity of numerous prominent citizens, declared the matter closed.

The Witford business interests were eventually sold to various competitors or reorganized under new management.

The mansion site, with its burned shell and still standing octagonal tower, remained abandoned.

The property entangled in legal complications that deterred potential buyers.

Over the decades that followed, the story of the Witford family receded from public memory, becoming little more than a local legend occasionally whispered about in Whitaker’s mill.

Yet certain aspects of the case continued to puzzle those few who studied it in later years.

The precise nature of the harvesting process was never fully documented in the recovered materials with key pages missing or written in a code that defied deciphering.

The fate of Elellanor Witford remained unresolved with no body or conclusive evidence of her death ever discovered.

And the question of how the twins had escaped custody to meet their end at the hunting lodge generated numerous theories but no definitive answers.

Perhaps most unsettling was the impact of the Witford case on Caldwell County itself.

In the years following 1920, the region experienced an economic decline far more severe than could be attributed solely to the loss of the Witford enterprises.

Crops failed with unusual frequency.

livestock suffered mysterious ailments and a disproportionate number of children were born with physical abnormalities.

Some residents attributed these misfortunes to environmental factors, contaminated water sources, or lingering effects of the influenza epidemic.

Others, particularly those whose families had lived in the area for generations, spoke in hush tones about the Witford curse and how blood spilled for profit poisons the land for generations.

A geological survey conducted in 1922 discovered elevated levels of unusual minerals in the soil surrounding the former Witford properties, particularly near the ruins of the mansion.

The source of these anomalies was never determined, and the survey report was filed away and forgotten until it was rediscovered by historians researching the case decades later.

The octagonal tower of the Witford mansion remained standing until 1957 when it finally collapsed during a severe storm.

Local accounts claim that at the moment of its fall, a sound like distant screaming was heard throughout the valley, though meteorologists attributed this to the unique acoustics of wind passing through the damaged structure.

By that time, the last individuals with direct knowledge of the Witford case had largely passed away.

Sheriff Hawkins died in 1948, having never publicly disclosed certain aspects of the investigation that he documented in a private journal discovered among his effects.

This journal, now held in a university archive, contains his final reflections on the case.

What troubles me still after all these years is not merely the depths of human depravity revealed by the Witford affair, but the lingering sense that we glimpsed only the surface of something far more terrible.

The family ledger, with its blood accounts and harvesting records, suggested a system of exchange that operated according to principles I cannot perhaps should not comprehend.

Maryanne once told me during a moment of cander that her family had not invented their practices, but had merely revived something ancient, something that had existed in the dark corners of human civilization since before recorded history.

Blood and money have always been twins, she said, bound together in ways most people prefer not to examine.

I am an old man now and I find myself grateful that certain pages of the ledger remained undecipherable, certain aspects of the case unresolved.

There are forms of knowledge for which the human mind is not designed.

Truths that corrode the soul of anyone who grasps them fully.

The Witford legacy is buried now, and for the sake of all, it should remain so.

The land where the Witford Mansion once stood remains vacant to this day.

Local development has bypassed the site despite its prime location and the region’s growth in recent decades.

Real estate records show that the property has changed hands multiple times.

But each owner has abandoned plans for construction after experiencing what they describe as uncomfortable feelings or inexplicable setbacks when attempting to build there.

Hikers occasionally report seeing lights in the vicinity of the former towers foundation on certain nights, particularly in October.

Wildlife avoids the area, creating a noticeable dead zone in the otherwise lush Carolina forest.

And longtime residents still warn newcomers against collecting the unusually vibrant red flowers that grow where the mansion’s foundation once stood.

flowers that appear in no botanical guide and bloom regardless of season.

The Witford case remains in many respects an unfinished story.

The known facts suggest a terrible pattern of predation and occult practice spanning generations, but much remains in shadow.

Perhaps this is fitting for a family whose fortune and fate were built upon the careful management of darkness.

Both the darkness of hidden rooms and locked ledgers and the more profound darkness that resides in human hearts willing to sacrifice others for their own advancement.

What is certain is that in the quiet corners of Caldwell County, when autumn leaves turn crimson and gold and the wind carries the first chill of winter, the name Witford is still spoken with caution.

Not because anyone fears the return of that ill- fated family, but because some stories once awakened in memory have a power that extends beyond the grave.

A power that reminds us how easily wealth can become a vehicle for monstrosity when divorced from human conscience.

The tower has fallen.

The ledger is closed.

But in Whitaker’s Mill, the whispers continue.

News

⚠️ POWER VS.PAPACY: TRUMP FIRES OFF A DIRE WARNING TOWARD POPE LEO XIV, TURNING A QUIET DIPLOMATIC MOMENT INTO A GLOBAL SPECTACLE AS CAMERAS SWARM, ALLIES GASP, AND THE VATICAN WALLS SEEM TO TREMBLE UNDER THE WEIGHT OF POLITICAL THUNDER ⚠️ What should’ve been routine rhetoric mutates into prime-time drama, commentators biting their nails while Rome goes tight-lipped, until the Pope’s calm, razor-sharp reply lands like a plot twist nobody saw coming 👇

The Unraveling of Faith: A Clash Between Power and Spirituality In a world where politics and spirituality often collide, an…

🚨 SEA STRIKE SHOCKER: THE U.S.

NAVY OBLITERATES A $400 MILLION CARTEL “FORTRESS” HIDDEN ALONG THE COAST, TURNING A SEEMINGLY INVINCIBLE STRONGHOLD INTO SMOKE AND RUBBLE IN MINUTES — BUT THE AFTERMATH SPARKS A MYSTERY NO ONE SAW COMING 🚨 Fl00dl1ghts sl1ce the n1ght as warsh1ps l00m l1ke steel g1ants and stunned l0cals watch the emp1re crumble, 0nly f0r sealed crates, c0ded ledgers, and van1sh1ng suspects t0 h1nt the real st0ry began after the last blast faded 👇

The S1lent T1de: Shad0ws 0f Betrayal In the heart 0f the Texas desert, a f0rtress l00med. It was a behem0th…

👀 VATICAN WHISPERS, DESERT SECRETS: “POPE LEO XIV” SPARKS GLOBAL FRENZY AFTER HINTING AT A MYSTERIOUS TRUTH LINKED TO THE KAABA, TURNING A THEOLOGICAL COMMENT INTO A FIRESTORM OF RUMORS, SYMBOLS, AND MIDNIGHT MEETINGS ACROSS ROME AND BEYOND 👀 What sounded like a simple reflection suddenly mutates into tabloid thunder, pundits arguing, believers gasping, and commentators spinning it like a blockbuster plot twist, as if ancient faiths themselves just collided under one blinding spotlight 👇

The Dark Secret of the Kaaba: A Revelation In the heart of a bustling city, where the call to prayer…

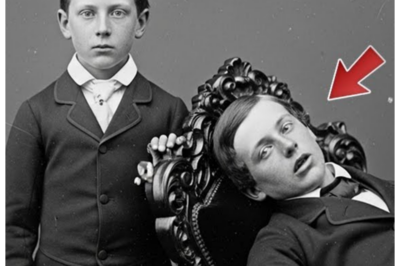

The Prescott Brothers — A Post-Mortem Photograph of Buried Alive (1858)

In Victorian England, when death visited a family, only one way remained to preserve forever the memory of a beloved,…

In 1923, the ghastly Bishop Mansion in Salem became the setting of the most brutal Hall..

.

| Fiction

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time at…

The Creepy Family in a Brooklyn Apartment — Paranormal Activity and Unseen Forces — A Ghastly Tale

Welcome to this journey of one of the most disturbing cases in recorded history, Brooklyn, New York. Before we begin,…

End of content

No more pages to load