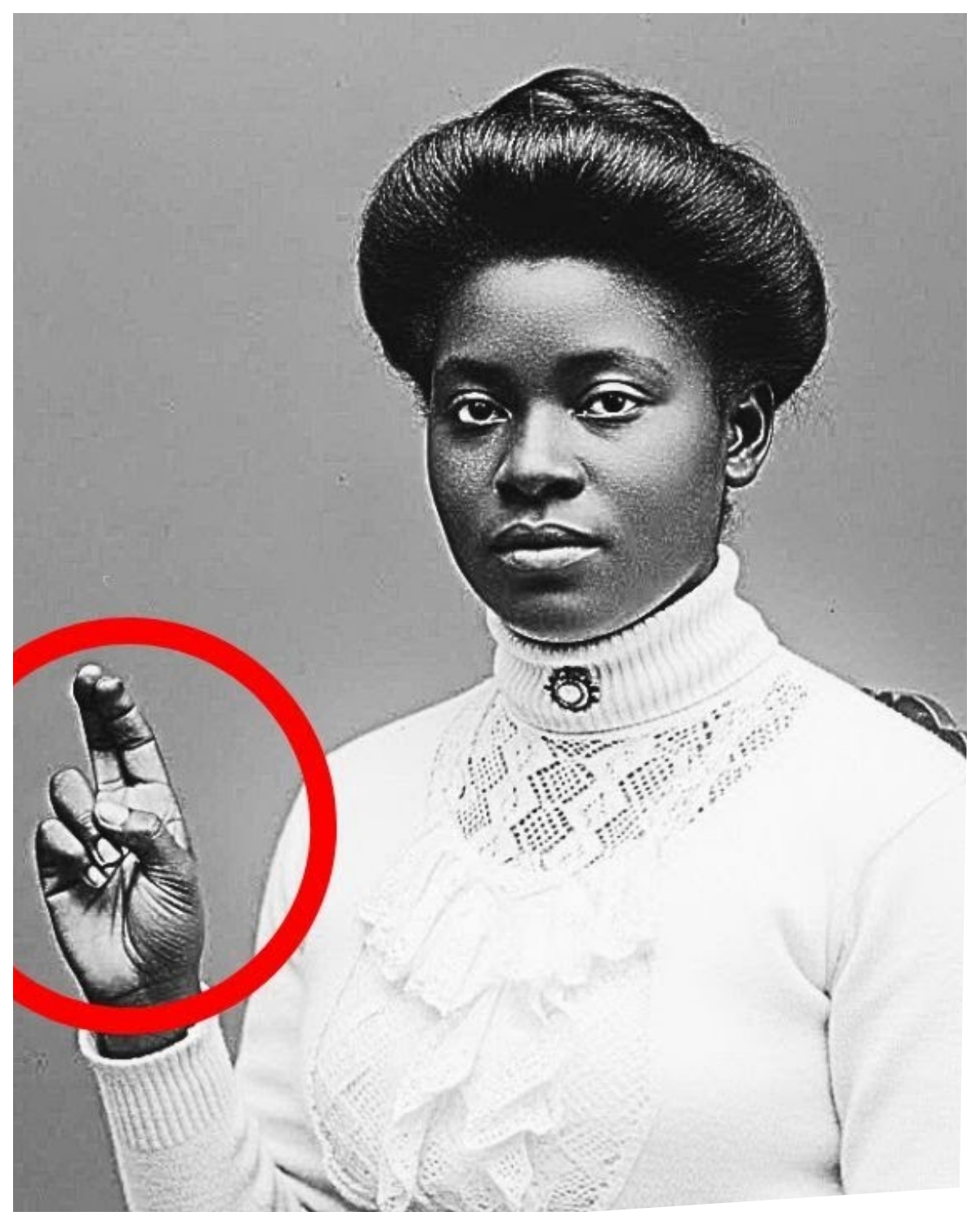

It was just a 1903 studio portrait until you saw the strange symbols on the woman’s hand.

Dr.Maya Richardson stood in the dimly lit auction house in Philadelphia, her fingers trembling slightly as she held the photograph up to the light.

The October rain drumed against the tall windows, casting shifting shadows across the rows of antique furniture and forgotten artifacts.

As a historian specializing in early African-American social movements, Maya had spent 15 years searching through archives, estate sales, and private collections, looking for untold stories buried beneath layers of official history.

This particular photograph had caught her eye immediately.

The auction catalog listed it simply as studio portrait, unknown subject, circa 1903.

The image showed a young black woman, perhaps in her late 20s, seated in a photographer’s studio with the formal rigidity typical of the era.

She wore a high-collared white blouse with delicate lace trim, her hair pulled back in a neat bun.

Her expression was composed, almost serene, but there was something in her eyes, a quiet defiance, a spark of intelligence that seemed to pierce through the decades.

Maya had almost passed it by.

She’d seen hundreds of similar portraits, beautiful but anonymous, their subjects names and stories lost to time.

But something made her look closer.

She pulled out her jeweler’s loop and examined the woman’s hands, which rested firmly on her lap.

Her breath caught on the woman’s right palm, barely visible in the sepia toned photograph were markings.

At first, Maya thought they might be damaged to the print itself, or perhaps shadows from the studio lighting.

But as she adjusted the angle, the patterns became clear.

Deliberate symbols, intricate and purposeful, etched or drawn under the woman’s skin.

Maya’s heart began to race.

She’d never seen anything like this in period photographs.

The symbols appeared to be geometric, circles intersecting with lines, small crosses.

what looked like stylized letters or numbers.

They were faint, as if the woman had tried to position her hand carefully to conceal them from casual observers, yet still preserve them for those who knew to look.

“That one’s $15?” the auctioneer called out, barely glancing in Maya’s direction.

“Going once for 15?” “50?” Mia said firmly, her voice cutting through the murmur of the crowd.

“She didn’t care about the price.

She knew with the certainty that comes from years of research and intuition that she was holding something extraordinary, a doorway into a hidden history that demanded to be opened.

Maya’s apartment in West Philadelphia was a controlled chaos of research materials.

Bookshelves sagged under the weight of historical texts.

Archival boxes were stacked in corners, and her dining table had long ago been converted into a permanent workspace.

She carefully placed the photograph under her high-powered digital microscope, connecting it to her laptop.

The November wind rattled her windows as she worked late into the night.

Her cat, Harriet, named after Tubman, watched from the windowsill with patient indifference.

Maya had canceled her morning lectures at the university, too consumed by what she was seeing on her screen.

The digital magnification revealed details invisible to the naked eye.

The symbols on the woman’s palm were definitely intentional, drawn with what appeared to be ink or henna.

There were seven distinct marks.

A circle with a horizontal line through it.

Two small crosses positioned at different angles.

What looked like the number three or a stylized letter M.

A vertical line with two dots, a crescent shape, and two parallel diagonal lines.

Maya photographed each symbol separately, then began cross-referencing them against every database she could access.

She searched through collections of early African-American fraternal organizations, church records, Masonic symbols, and documentation of secret societies.

Nothing matched.

Around 3 in the morning, exhausted and frustrated, she turned to the back of the photograph.

Studio portraits from this era typically bore the photographers’s imprint.

This one was no exception.

Thornton and Sun’s photography studio, Washington, DC, estosed in fading gold letters.

Washington DC in 1903.

Maya’s historian’s mind began making connections.

This was during the height of the progressive era, but also a time of increasing segregation and disenfranchisement for black Americans.

The National Association of Colored Women had been founded just 7 years earlier.

Ida B.

Wells was still actively campaigning against lynching, and the struggle for women’s suffrage was gaining momentum, though black women were often excluded from white suffragist organizations.

Maya pulled up census records, city directories, and business registries for Washington DC in the early 1900s.

Thornton and Sons had been located on Ust Street in the heart of what would later be known as Black Broadway, a thriving African-American cultural and business district.

Her phone buzzed.

A text from her colleague, Dr.

James Chen, a symbology expert at Georgetown.

You still up? Saw your email about the symbols.

Can meet tomorrow afternoon if you want a second opinion.

Mia smiled, typing back quickly.

Tomorrow couldn’t come soon enough.

Dr.

James Chen’s office at Georgetown University was the opposite of Mia’s chaotic workspace, meticulously organized with artifacts displayed in glass cases and reference books arranged by subject and date.

He greeted Maya with his characteristic warm smile, adjusting his wire- rimmed glasses as she carefully removed the photograph from its protective sleeve.

“You weren’t exaggerating,” James murmured, examining the image under his own equipment.

“These symbols are deliberately placed.

” The woman positioned her hand just so enough to capture them in the photograph, but subtle enough that a casual viewer wouldn’t notice.

That’s sophisticated.

Maya leaned over his shoulder, watching as he traced each symbol on his tablet, creating digital renderings.

The afternoon light filtered through his office window, illuminating dust moes in the air.

Outside, Georgetown students hurried between classes, their voices a distant murmur.

“This one,” James said, pointing to the circle with the horizontal line resembles astronomical or navigational symbols, but the context is all wrong.

In these crosses, they’re not religious in the traditional sense.

The angles are too specific, too deliberate.

Right? He pulled up several reference databases on his computer, running image recognition software against archives of historical symbols from secret societies, trade guilds, and political organizations.

Maya watched the screen flicker through hundreds of possibilities, each one rejected by the algorithm.

What if they’re not established symbols? Maya suggested.

What if they’re original, a code created for a specific purpose? James sat back, considering that would make sense if we’re dealing with clandestine communication.

During this period, many marginalized groups developed their own symbolic languages.

The question is, what was this woman trying to communicate and to whom? Maya pulled out her notebook where she’d sketched her preliminary research.

I’ve been thinking about the context.

Washington, DC, 1903.

Black women were fighting for both racial equality and gender equality, but they were systematically excluded from mainstream suffrage organizations.

The National American Women Suffrage Association was actively courting southern white women and distancing itself from black activists.

So they would have needed their own networks.

James continued, his eyes brightening with understanding their own ways of organizing, communicating, identifying allies.

Exactly.

And if you wanted to preserve evidence of that network to document it for future generations, what better way than a photograph? Something that looks completely ordinary but carries hidden information.

James enhanced one of the symbols on his screen, the crescent shape.

This could represent a meeting time.

Crescent moon, specific lunar phase perhaps, or location.

Maya added there was a crescent street in the Shaw neighborhood of DC.

It was renamed in the 1920s.

They worked through the afternoon developing theories, discarding implausible ones, building hypotheses.

By evening, they had a framework.

The symbols likely represented a communication system, possibly indicating meeting places, times, or warnings within an underground network of black suffragists.

But they still didn’t know who the woman was.

The Library of Congress loomed before Maya.

Its Bozar’s architecture imposing against the gray December sky.

She’d requested access to the manuscript division’s collection of early 20th century African-American organizational records.

A sprawling archive that few researchers had thoroughly explored.

The reading room was hushed, filled with the rustle of turning pages, the soft clicking of laptop keyboards.

Maya had been here for three days straight, working through boxes of correspondents, meeting minutes, membership lists, and newspaper clippings from black women’s clubs, church groups, and civic organizations active in Washington DC between 1900 and 1910.

Her eyes burned from reading faded handwriting and microfilm, but she couldn’t stop.

Somewhere in this vast collection was a connection to the woman in the photograph.

On the afternoon of the third day, in a box labeled Colored Women’s League of Washington, correspondence 1902 and 1905, Maya found something that made her pulse quicken.

It was a letter dated March 15th, 1903, written in elegant cursive on cream colored stationary.

Dear Sister Josephine, the matter we discussed at the last gathering requires utmost discretion.

Our sisters in Baltimore have established their circle successfully using the marks we agreed upon.

I have commissioned a portrait at Thornon Studio, as you suggested, to preserve our record.

The photographer is sympathetic to our cause and asks no questions.

We must be careful.

The opposition grows bolder each day.

Remember our sign in solidarity.

CM.

Maya’s hands trembled as she photographed the letter CM.

The initials matched several women in the league’s membership roster, but one name appeared repeatedly in the correspondence.

Clara Montgomery.

She pulled up the membership list again.

Clara Montgomery, born 1876 in Richmond, Virginia, moved to Washington DC in 1899.

occupation listed as school teacher active in the colored women’s league, the Baptist Women’s Convention.

And this was new, something called the Citizens Rights Circle.

Maya had never heard of the Citizens Rights Circle.

She searched through every database, every index, nothing.

It didn’t appear in any historical record she could access, which meant it was either extremely obscure or deliberately hidden.

She gathered her materials and headed to the archives reference desk, where a librarian named Mrs.

Patterson, who’d helped Maya numerous times over the years, was sorting through request slips.

“Mrs.

Patterson, have you ever come across any references to something called the Citizens Rights Circle, active in DC around 1903?” The elderly librarian paused, her expression thoughtful.

“Can’t say I have, Dr.

Richardson, but you might want to check with the Morland Spingern Research Center at Howard.

They have materials that never made it into our collection.

Family papers, church archives, that sort of thing.

If it was a grassroots organization in the black community, they’re more likely to have records.

Maya checked her watch.

The research center would be open for another 2 hours.

She gathered her things and headed out into the cold December evening, her breath forming clouds in the air as she walked quickly toward the metro station.

Howard University’s campus was quieter during winter break, most students having left for the holidays.

Maya walked through the historic grounds, past Frederick Douglas Memorial Hall, toward the Morland Spingard Research Center.

The building housed one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of materials documenting the black experience.

Dr.

Evelyn Harper, the senior archivist, greeted Maya in the reading room.

She was a woman in her 60s with silver streaked hair and the kind of institutional knowledge that comes from decades of careful stewardship.

Dr.

Richardson, good to see you again.

Your email about the Citizens Rights Circle intrigued me.

I did some preliminary searching after you contacted me.

Maya’s hopes rose.

Did you find anything? Dr.

Dr.

Harper led her to a research table where she’d laid out several items.

Not much, I’m afraid, but what we have is fascinating.

The Citizens Rights Circle appears to have been active between approximately 1901 and 1908, primarily in DC, Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

It was an underground organization of black women advocating for voting rights, not just women’s suffrage, but universal suffrage that would include all black citizens.

Oh.

She opened a fragile scrapbook protected by archival tissue.

This belonged to Reverend Sarah Watkins who pastored a small Baptist church in Shaw.

Her granddaughter donated it to us in 1987.

Look at this entry from 1904.

Maya leaned in reading the careful handwriting.

Attended the circle’s quarterly gathering.

Sister Clara spoke with great passion about the need for our own methods of organization.

As the white suffragists will not stand with us, we have adopted the marks of identification which each member will carry as a sign of our commitment and a means of recognition in times of danger.

Marks of identification.

Maya whispered.

The symbols.

Dr.

Harper nodded.

I believe the citizens right circle developed a symbolic language, a visual code that members could use to identify each other and communicate safely.

Remember, this was during a period of intense violence against black activists.

Women in this movement faced threats from white supremacist groups, and they couldn’t necessarily trust law enforcement.

They needed ways to operate below the radar.

She pulled out another document, a faded photograph of a group of women standing in front of a church.

This was taken in 1905.

Notice anything unusual? Maya examined the image closely.

There were about 20 women, all formally dressed, their expressions serious, and then she saw it.

Several of them had positioned their hands in similar ways, palms slightly turned toward the camera.

They’re displaying the symbols, Maya breathed.

I believe so.

The marks were subtle enough to avoid detection by hostile observers, but visible enough for those who knew what to look for.

A brilliant security measure.

Maya felt the weight of discovery settling over her.

These women had been erased from official suffrage history, their contributions forgotten or deliberately excluded, but they’d left breadcrumbs, coded messages hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone to decipher them.

Dr.

Harper, do you have any records identifying the individual members? I’m particularly looking for Clara Montgomery.

The archist smiled.

Follow me.

In a climate controlled storage room, Dr.

Harper retrieved a banker’s box labeled Montgomery Family Papers, 1870 1920.

Inside were letters, certificates, photographs, and a leatherbound journal with Clara Montgomery’s name embossed on the cover.

Maya’s hands shook as she carefully opened the journal.

The entries began in January 1901, when Clara had just moved to Washington, DC from Richmond.

Her handwriting was precise and elegant, her observations sharp and often tinged with frustration.

January 10th, 1901.

Arrived in the capital today.

The train journey was long and uncomfortable.

We were relegated to the colored car which was overcrowded and poorly ventilated.

But I am here now, ready to begin teaching at the Frederick Douglas School.

Mother worries I am too outspoken for my own good.

Perhaps she is right.

But silence is a luxury I cannot afford.

Amaya read through months of entries watching Clara’s life unfold.

She taught history and literature to black children, attended church meetings, joined the colored women’s league.

Her entries revealed a woman of fierce intelligence and determination, increasingly frustrated by the limitations placed on her life simply because of her race and gender.

Then in November 1901, the tone shifted.

November 18th, 1901, met with a group of like-minded women tonight at Sister Josephine’s home.

We spoke openly, perhaps dangerously, about our rights, not as a future possibility, but as a present demand.

We discussed forming our own organization.

Separate from the white suffragists who patronize us and from the black men’s organizations that ask us to wait our turn.

Our turn is now.

We will call ourselves the Citizens Rights Circle.

Over the following months, Clara’s entries documented the circle’s growth and activities.

They held secret meetings in church basement and private homes.

They organized quiet boycots of businesses that discriminated against them.

They raised funds for legal challenges to discriminatory laws.

And they developed their symbolic code.

March 12th, 1903.

We finalized our marks today.

Each symbol carries meaning.

The circle with the line represents unity and equality.

The crosses mark meeting places.

The crescent indicates midnight gatherings.

The vertical line with dots signifies danger or surveillance.

We must be able to recognize each other and communicate without words, for words can be overheard and used against us.

Tomorrow I will have my portrait made at Thornton’s studio.

Sister Josephine insists we must document ourselves, preserve evidence of our work for future generations.

who may wonder if we even existed.

Maya looked up from the journal, her vision blurred with tears.

She was reading the words of the woman in the photograph.

The same woman whose image had been reduced to unknown subject circa 1903 in an auction catalog.

Clara Montgomery wasn’t unknown.

She had a name, a voice, a story.

She had been a teacher, an organizer, a revolutionary hiding in plain sight.

Dr.

Harper placed a hand on Mia’s shoulder.

You found her.

Yes, Mia whispered.

And I need to find her family.

They deserve to know who she was.

No.

Finding Clara Montgomery’s living descendants proved easier than Maya expected.

The Montgomery family papers included a detailed family tree meticulously maintained through generations.

Clara had married in 1907, had three children, and lived until 1958, passing away in her Washington DC home at the age of 82.

Her great great granddaughter Simone Carter lived in Silver Spring, Maryland, just outside DC.

Maya founder through a combination of genealological databases and social media then sent a carefully worded email explaining her research.

The response came within hours.

Dr.

Richardson, I would very much like to meet you.

My family has always known that great great-grandmother Clara was involved in activism, but we have very few details.

Sunday afternoon at my home.

Sunday arrived cold and bright with snow beginning to fall as Maya drove to Silver Spring.

Simone’s house was a warm, welcoming split level filled with the sounds of family, children playing, music from a kitchen radio, the rich smell of cooking greens, and cornbread.

Simone was a woman in her early 40s, a high school principal with Clara’s same intelligent eyes and determined chin.

She greeted Mia warmly, then led her to the living room where several family members had gathered.

Simone’s mother, her aunt, two cousins, and her teenage daughter.

Mia spread out her research materials on the coffee table.

the photograph, copies of Clara’s journal entries, the documents from the citizen’s right circle.

The room fell silent as family members examined each item.

Simone’s mother, Mrs.

Angela Carter, picked up the photograph with trembling hands.

“I’ve never seen this picture before.

Look at her.

So young, so serious.

We have some photos of her from when she was older, but nothing from this time in her life.

” “The symbols on her hand,” Simone said, studying the image closely.

“We had no idea.

What did they mean?” Maya explained the citizens rights circle, the coded communication system, the underground network of black women fighting for their rights decades before the victories of the civil rights movement.

She described how Clara and her fellow activists had operated in secret, knowing that visibility could mean violence or worse.

They couldn’t march openly, couldn’t organize publicly the way the white suffragists did, Maya explained.

So, they developed their own methods.

The symbols were a way to identify allies, share information, arrange meetings, and by having them photographed, Clara was preserving evidence of their work, leaving proof for future generations.

Simone’s teenage daughter, Trinity, spoke up.

So, my great great great grandmother was basically a spy.

That’s amazing.

Not exactly a spy, Maya said with a smile.

But she was operating in resistance.

She and the other women of the circle were risking their safety and livelihoods, to fight for rights that wouldn’t be fully recognized for decades.

Black women didn’t get the practical right to vote in many places until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, more than 60 years after this photograph was taken.

Mrs.

Carter wiped tears from her eyes.

We always knew she was special.

She lived with my grandmother for the last years of her life.

And even when she was very old, she would tell us stories about the work.

We thought she just meant teaching.

We had no idea.

Can we have copies of the journal? Simone asked.

And the other documents? This is our family history.

Absolutely, Maya assured her.

And I’d like to work with you on a larger project, documenting Clara’s story and the citizens right circle, bringing this hidden history to light.

The family spent the rest of the afternoon sharing stories, looking through old photo albums, piecing together Clara’s life beyond the activism.

She had been a beloved teacher, a devoted mother, a talented baker famous for her peach cobbler.

She had loved reading, especially poetry.

She had sung in the church choir.

She had been a complete person, not just a symbol or a historical figure, but a woman with dreams, fears, joys, and struggles.

As Maya prepared to leave, Trinity approached her with a question.

Dr.

Richardson, why do you think she put the symbols where people could see them, even if it was risky? Maya considered the question carefully.

I think she wanted to be seen, not just by her contemporaries, but by us, by people in the future.

She wanted us to know that she existed, that she fought, that she mattered.

And now, more than a century later, we do know, and we can tell her story.

The Washington Post conference room overlooked K Street, the winter cityscape, gray and sharp beyond the windows.

Mia sat across from journalist Kesha Williams, who specialized in historical features with contemporary relevance.

Between them lay the photograph, Clara’s journal, and Mia’s research notes.

Kesha studied the materials with the focused attention of an experienced reporter.

This is extraordinary, Dr.

Richardson.

A secret network of black suffragists operating underground while history focused on the white suffrage movement.

The timing is perfect, too.

We’re in an era where people are hungry for untold stories for the voices that were deliberately silenced.

That’s why I wanted to bring this to you.

Maya said Clara and the women of the citizens rights circle deserve recognition.

Their strategies, their courage, their vision.

It all needs to be part of the national conversation about suffrage history.

Kesha made notes on her tablet.

I’ll need to verify everything independently, of course, interview the family, consult other historians, confirm the archival sources.

But if this checks out, and I believe it will, we’re looking at a major feature, possibly a series.

Have you considered the broader implications? This could reshape how we teach suffrage history.

I’ve been thinking about nothing else, my admitted for too long, the narrative has centered white women and their struggles, while erasing or minimizing the contributions of black women who faced both racism and sexism.

Clara and her colleagues weren’t just fighting for the vote.

They were fighting for fundamental human dignity in a society that denied both their race and their gender full citizenship.

Over the next two weeks, Kesha worked on the story, conducting interviews and verifying sources.

She spoke with the Montgomery family, with Dr.

Harper at Howard, with James Chen about the symbols, with other historians who specialized in black women’s history.

The article grew into a major investigative feature.

On a cold February morning, the story broke online.

The Secret Code of the Suffragists, how black women fought for the vote in plain sight.

The response was immediate and overwhelming.

Within hours, the article had been shared thousands of times on social media.

Historians, educators, activists, and general readers engaged with Clara’s story, expressing shock that this history had been so thoroughly buried.

Pride in the ingenuity and courage of these forgotten women, and determination to ensure their stories were finally told.

Maya’s phone buzzed constantly with messages.

Interview requests from NPR, the BBC, local news stations, emails from other researchers who’d found similar coded photographs in their own collections, messages from descendants of other citizens rights circle members asking if she could help them learn about their ancestors.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture called expressing interest in acquiring the photograph and related materials for their permanent collection.

The National Archives wanted to collaborate on a comprehensive oral history project documenting the circle’s activities and impact.

Maya sat in her apartment that evening, exhausted but elated, watching the sun set over Philadelphia.

Harriet the cat curled in her lap, purring softly on her laptop screen.

The photograph of Clara Montgomery glowed in the fading light.

That young woman with her quiet defiance and her hidden symbols, finally seen, finally recognized, finally claiming her place in history.

Her phone rang.

It was Simone Carter.

Dr.

Richardson, my family and I, we don’t know how to thank you.

My daughter has been reading everything she can find about Clara, and she’s writing a paper about her for her history class.

She’s so proud.

We all are.

Amaya felt tears welling up.

Clara did the work.

I just helped bring it to light.

That’s everything, though.

That’s what she wanted for someone someday to look closely enough to see.

And you did.

6 months later, the National Museum of African-American History and Culture unveiled a special exhibition, Coded Courage, the secret language of black and women suffragists.

The opening reception drew hundreds of people, scholars, activists, descendants of circle members, politicians, students, and curious visitors who’d followed the story since the Washington Post article broke.

Maya stood near the entrance watching people file in.

The exhibition design was stunning.

The main gallery featured enlarged versions of coded photographs, including Clara’s portrait as the centerpiece.

Interactive displays explained the symbol system, while touchcreens allowed visitors to explore digitized versions of letters, journals, and meeting minutes.

Personal artifacts, a suffrage pin, a handwritten speech, a worn Bible brought the women’s daily lives into focus.

One section of the exhibition contextualized the citizens right circle within the broader suffrage movement using timeline graphics to show how black women were systematically excluded from white organizations while also facing resistance from some black male leaders who argued that women’s suffrage should wait until racial equality was achieved erea overheard a young visitor say to her friend but they didn’t wait they just found another way and her family arrived Trinity wearing a custom t-shirt featuring Clara’s photograph they moved through the exhibition together, reading every placard, watching every video, examining every artifact.

When they reached Clara’s portrait, now professionally restored and beautifully lit, they stood in silence for a long moment.

“Look at her hand,” Trinity said softly, pointing to the enlarged image where the symbols were now clearly visible.

“She’s talking to us.

She’s saying, I was here.

We were here.

Don’t forget us.

” Mrs.

Carter nodded, wiping her eyes.

“And we won’t.

Not anymore.

” The exhibition included a section on the modern implications of Clara’s work, how the organizing strategies of the citizens rights circle influenced later civil rights activists, how their emphasis on underground networks and coded communication prefigured the security measures used by freedom writers and voter registration workers in the 1960s.

Dr.

Harper had contributed to this section, providing historical analysis that connected Clara’s generation to subsequent waves of activism.

What’s remarkable, her wall text explained, is how these women understood that resistance takes many forms.

When overt organizing was dangerous, they went underground.

When their voices were excluded from mainstream platforms, they created their own communication channels.

When history threatened to erase them, they left coded messages for future generations to decipher.

As the reception continued, Maya was approached by a young woman who introduced herself as a graduate student researching black women’s organizing in Baltimore.

I think I found evidence of another circle chapter, she said excitedly.

In my grandmother’s attic, there’s a trunk full of papers from a church group in the 1900s, and some of the correspondence mentions the marks.

I had no idea what it meant until I read about your discovery.

Why, I felt a surge of hope.

That’s wonderful.

We’re only beginning to uncover this history.

There are probably dozens of women whose stories are still waiting to be told.

Throughout the evening, similar conversations unfolded.

Descendant families found each other, comparing notes about their ancestors.

Researchers shared leads and sources.

Young activists drew connections between historical organizing strategies and contemporary movements.

As the crowd thinned and the reception wound down, Maya found herself alone again with Clara’s portrait.

She thought about the long journey from that auction house in Philadelphia to this moment.

From unknown subject to honored ancestor, from forgotten to celebrated.

James Chen joined her, carrying two glasses of champagne.

To Clara, he said, raising his glass.

To Clara, Mia echoed.

And to all the women whose stories we’re still searching for.

One year after the exhibition opened, Mia stood in a very different setting, a high school auditorium in Shaw, Washington, DC, just blocks from where Clara Montgomery had once taught.

She was there to speak to students about historical research methods.

But the real purpose, as the history teacher had explained, was to inspire young people to see themselves in history.

The auditorium was packed with teenagers, their energy palpable as they settled into seats.

Maya noticed that several wore t-shirts featuring the now iconic image of Clara’s photograph, the symbols on her hand clearly visible in the design.

How many of you have heard of the citizens right circle? May I asked? Nearly every hand in the room went up.

A year ago, almost no one knew this history existed.

Now it was being taught in schools across the country, included in updated textbooks, featured in documentaries.

Good, Maya continued.

Then you know that history isn’t just about what’s written in official records or celebrated in monuments.

Sometimes the most important stories are hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone to look closely enough to see them.

She clicked to a slide showing Clara’s portrait, the image now familiar to millions.

When I first found this photograph, it was cataloged as unknown.

No name, no story, just an anonymous face from the past.

But Clara Montgomery wasn’t anonymous.

She was a teacher, an activist, a wife, a mother.

She was brave and brilliant and she made sure we would find her.

Trinity Carter, now a sophomore in the school student body president, raised her hand.

Dr.

Richardson, how many other women like my great great great grandmother are still out there still unknown? It was the question Maya had been asking herself for months.

Honestly, probably thousands.

The Citizens Rights Circle had chapters in at least a dozen cities.

We’ve identified about 40 members so far, but the organization likely included many more.

And they weren’t the only group.

There were other networks, other movements, other brilliant women whose contributions were deliberately erased from official history.

She paused, looking out at the sea of young faces.

That’s where you come in.

You are the next generation of researchers, truthtellers, and history keepers.

In your atticss, your family archives, your church basement, there are probably photographs, letters, and documents that hold pieces of this puzzle.

Your job is to look closely, ask questions, and refuse to accept that anyone is truly unknown.

After the presentation, students crowded around with questions and stories.

One boy showed Maya a photograph of his great-grandmother at a protest in the 1940s.

A girl mentioned finding old suffrage pins in her grandmother’s jewelry box.

A young person asked how to start researching their family history.

Later, as Maya packed up her materials, the history teacher approached, “Thank you for this.

You’ve given these kids something precious.

Proof that people who looked like them, who came from neighborhoods like theirs, changed history.

That matters more than you know.

Driving back to Philadelphia that evening, Maya reflected on the year since she’d first held Clara’s photograph in that auction house.

The discovery had transformed her own career.

She’d published articles, given lectures worldwide, received grant funding for expanded research, but more importantly, it had sparked a broader reckoning with how American history is told and who gets remembered.

The exhibition had traveled to six cities and was scheduled for 10 more.

The Smithsonian had established a research fellowship in Clara Montgomery’s name, funding scholars studying hidden histories of black women’s activism.

Multiple universities had revised their suffrage history curricula to include the citizens rights circle.

And the Montgomery family, Simone, Mrs.

Carter, Trinity, and dozens of relatives across the country had become keepers of Clara’s legacy, speaking at events, sharing family stories, ensuring that their ancestors courage continued to inspire new generations.

Maya’s phone buzzed with a text from Simone.

Trinity got an A+ on her research paper about Clara.

She’s thinking about becoming a historian.

Thank you for everything.

Maya smiled, typing back, “Tell her historians don’t discover history.

They recover it.

” And there’s so much left to recover.

As she drove through the Maryland countryside, the late afternoon sun casting long shadows across the landscape, Ma thought about all the photographs still sitting in auction houses, attics, and archives, all the stories still waiting to be seen.

all the women who’d left breadcrumbs, hoping someone would follow the trail.

Clara Montgomery had smiled for a camera in 1903, carefully positioning her hand to reveal her secrets.

121 years later, her message had finally been received and understood.

She had existed.

She had fought.

She had mattered.

And she was no longer unknown.

News

It was just a portrait of newlyweds — until you see what’s in the bride’s hand

It was just a portrait of newlyweds until you see what’s in the bride’s hand. The afternoon light filtered through…

It Was Just a Photo of a Mother and Child — Until You Saw the Symbol Hidden in Her Fingers

It was just a photo of a mother and child until you saw the symbol hidden in her fingers. Dr.Maya…

No one ever noticed what was wrong with this 1930 family portrait — until it was restored

No one ever noticed what was wrong with this 1930 family portrait until it was restored. Jennifer Hayes carefully removed…

Why were Experts Turn Pale When They enlarged This Portrait of Two Friends from 1888?

Why did experts turn pale when they zoomed into this portrait of two friends from 1888? The digital archive room…

It was just a portrait of two sisters — and experts pale when they notice the younger sister’s hand

It was just a portrait of two sisters, and experts pale when they noticed the younger sister’s hand. The photograph…

🌲 VANISHED IN MONTANA — THREE YEARS LATER HIS BODY EMERGES WRAPPED INSIDE A DEAD TREE, AND THE FOREST SPEAKS A NIGHTMARE 🩸 What was thought to be another missing-person case turned into a grotesque revelation when hikers stumbled upon the hollowed trunk, realizing the wilderness had been hiding a chilling secret, and investigators were left piecing together a story of cruelty and concealment that sent shivers through the state 👇

The first thing people noticed was the silence. Not the peaceful kind that hikers chase, but the wrong kind, the…

End of content

No more pages to load