They Restored This 1900 Wedding Photo — and Found Something Written in the Bride’s Veil

They restored this 1900 wedding photo and found something written in the bride’s veil.

The photograph arrived at Maya Richardson’s studio on a humid Tuesday afternoon in Charleston, wrapped in brown paper and smelling faintly of lavender and old wood.

Maya had been restoring historical photographs for 8 years, working out of a converted warehouse near the waterfront, where the afternoon light filtered through tall windows, illuminating centuries of forgotten faces waiting to be brought back to life.

She carefully unwrapped the package, her practiced fingers moving slowly to avoid any damage.

Inside was a wedding photograph from 1900.

Its sepia tones faded to near invisibility in places.

The emulsion cracked and peeling at the edges.

But even through the damage, Maya could make out two figures standing before what appeared to be a simple alter, their faces barely visible through the deterioration of time.

The accompanying letter was from Robert Chen, a local history professor, who had found the photograph in his late grandmother’s attic.

He explained that the image had been passed down through his family, though no one remembered who the couple was or why the photograph had been kept.

He hoped Maya could restore it enough to identify the people and perhaps solve a small family mystery.

Maya placed the photograph under her magnifying lamp and began her initial assessment.

The bride wore a simple white dress with long sleeves, typical of the era, and a veil that cascaded down past her shoulders.

The groom stood beside her in a dark suit, his posture formal and rigid, as was customary for photographs of that time.

The background showed minimal decoration, suggesting either a private ceremony or perhaps limited means.

As Maya examined the image more closely, something struck her as unusual.

The bride’s skin tone, even through the fading and damage, appeared darker than typical for the era’s wedding photographs she had restored.

She leaned closer, adjusting the light.

The groom was undeniably white, his pale skin visible even through the photograph’s deterioration.

Maya felt her heartbeat quicken [music] slightly.

an interracial couple in 1900 in the South.

She knew the history well.

Such unions were not just socially taboo in that era.

They were dangerous, often illegal, and could result in violence.

If this photograph was genuine, it represented something extraordinary, a testament to courage that most people in 2024 couldn’t begin to comprehend.

Maya pulled out her notebook and began documenting her initial observations.

She would need to be methodical, careful, and thorough.

This wasn’t just a restoration job anymore.

This was a window into a story that had been hidden for over a century, and she had a responsibility to honor whatever truth lay within these faded layers of silver and time.

Maya spent the next morning preparing the photograph for digital scanning.

She worked in her climate controlled restoration room, where temperature and humidity were carefully monitored to protect the fragile materials she handled daily.

The wedding photograph lay flat on her scanner bed, positioned with archival gloves and precision tools.

The highresolution scanner hummed to life, its light bar moving slowly across the image, capturing every microscopic detail at 2400 dots per inch.

Maya watched the preview screen as the digital file emerged, revealing textures and details invisible to the naked eye.

The process took nearly 20 minutes, but she never rushed this stage.

Patience was the foundation of good restoration work.

When the scan completed, Mia opened the file in her specialized restoration software.

She zoomed in to 400% magnification, beginning her systematic examination of every section of the photograph.

She started with the faces, noting the bride’s gentle expression and the groom’s solemn gaze.

Both looked young, perhaps in their early 20s, their eyes holding a mixture of hope and determination.

As she moved across the image, documenting areas of damage and planning her restoration approach, Maya reached the bride’s veil.

The fabric appeared delicate, even in the photograph, with what looked like lace or fine embroidery along its edges.

She increased the magnification to 800%.

Examining the texture and pattern.

Then she saw them.

Letters.

Tiny, impossibly small letters woven or embroidered into the veil’s fabric near the bride’s left shoulder.

Maya’s breath caught in her throat.

She adjusted the contrast and sharpness settings, bringing the letters into clearer focus.

They were deliberately placed, too intentional to be a pattern or decorative element.

Her hands trembled slightly as she zoomed in further to maximum magnification.

The letters formed words, though many were obscured by the photograph’s damage and the angle of the veil.

She could make out fragments.

[music] Safe, what might be harbor, and what looked like numbers, possibly coordinates or an address.

[music] Maya leaned back in her chair, her mind racing.

Someone had encoded a message into the bride’s wedding veil.

But why? And for whom? She thought about the era, the danger this couple must have faced, the necessity of secrecy.

Had the veil contained instructions for others, a map to safety, a coded message that only certain people would know to look for.

She picked up her phone and called Robert Chen, the professor who had sent her the photograph.

After three rings, he answered with a cheerful greeting.

Maya’s voice was steady but excited as she spoke.

Professor Chen, I need to ask you something.

Did your grandmother ever mention anything about helping people, about networks or safe houses, anything related to the early 1900s? There was a long pause on the other end.

That’s a very specific question.

Why do you ask? Because, Mia said, her eyes fixed on the screen before her.

I think this photograph is hiding something important, something that people risked their lives to preserve.

Robert Chen arrived at Ma’s studio within the hour, his gray hair slightly disheveled from the wind, his eyes bright with curiosity behind wire- rimmed glasses.

He was in his late 60s, a respected historian at the College of Charleston who specialized in reconstruction era South Carolina.

Maya had worked with him before on various restoration projects, and she trusted his expertise and discretion.

She led him to her workstation, where the magnified image of the veil still glowed on her monitor.

Robert leaned forward, squinting at the screen, then removed his glasses to clean them before looking again more carefully.

His expression shifted from curiosity to astonishment as he began to make out the tiny letters woven into the fabric.

“My God,” he whispered.

“I’ve heard stories, but I never thought they were connected to my family.

” Maya pulled up a chair for him.

What stories? Robert sat down slowly, his eyes never leaving the screen.

My grandmother Sarah used to talk about her grandmother, who supposedly helped people during what she called the difficult years.

I always assumed she meant during the depression or maybe during the World Wars, but she was always vague about it, like it was something that couldn’t be spoken about directly, even decades later.

He pointed to the screen.

Can you enhance this? Make the letters clearer? Maya nodded and opened her enhancement tools.

She applied various filters, adjusting contrast and sharpness, carefully revealing more of the hidden text without distorting the image.

Slowly, more words emerged from the veil’s fabric.

Safe Harbor, Northstar Church, Third House Beyond the Oak, not twice, then once.

Robert’s hand went to his mouth.

Northstar Church.

I know that name.

It was an African Methodist Episcopal Church that operated in Charleston from 1895 until it burned down in 1908.

The fire was ruled suspicious, [music] but no one was ever charged.

He turned to Mia, his voice urgent.

Do you understand what this means? This wasn’t just a wedding veil.

It was a guide.

Maya felt the weight of the discovery settling over her.

A guide for what? For whom? For couples like the ones in this photograph, Robert said, standing and pacing now, his academic mind clearly working through the implications.

[music] Interracial marriage was illegal in South Carolina until 1967.

In 1900, it wasn’t just illegal, it was unthinkable to most people.

Couples who wanted to marry had to leave the state, usually going north to places where laws were less restrictive.

But even then, coming back home was incredibly dangerous.

He turned back to the photograph.

Someone created a network, a way to help these couples marry legally and then return home safely, or at least as safely as possible.

The veil was the key.

The map passed from one couple to another.

Maya zoomed out to show the full photograph again.

So this couple, whoever they were, they used this network.

more than that,” Robert said, his voice filled with wonder.

“If my family kept this photograph for over a century, hidden in an attic, then maybe my ancestors were part of that network.

Maybe they were the ones helping people.

” The Charleston County Public Library special collections room smelled of old paper and preservation chemicals, a scent Maya had come to associate with discovery.

She and Robert sat at a long wooden table covered with archival boxes, their contents carefully organized by decade and subject.

They had been searching for 3 hours looking for any mention of Northstar Church or interracial marriages in the early 1900s.

Robert pulled out a leatherbound ledger, its pages brittle with age.

This is from the Recorder of Deed’s office, 1898 to 1902.

Marriage licenses, property transfers, deaths.

He turned the pages carefully, his finger tracing down columns of faded ink.

The problem is that illegal marriages wouldn’t be recorded here.

We’re looking for absences as much as presences.

Yes.

Maya was examining a box of church records, newsletters, and announcements from various congregations.

Most were from white churches, their pages filled with social events and mission work.

Then she found a thin folder labeled simply Northstar amme final records 1908.

Her hands trembled as she opened it.

Inside were water damaged documents, some partially burned, salvaged from the church fire Robert had mentioned.

There were membership lists, baptismal records, and then something that made her heart race.

a handdrawn map on a piece of cloth similar to linen showing Charleston’s streets with small X marks at various locations.

“Robert,” she said quietly.

He looked up from his ledger and moved to her side.

Together, they studied the map.

The X marks were concentrated in certain neighborhoods, some with tiny initials beside them.

One location, marked with a star instead of an X, was labeled NH in pencil, so faint it was barely visible.

North Harbor, Maya suggested.

Or North House.

Robert shook his head slowly.

No, look at the pattern.

These marks are in predominantly black neighborhoods, but a few are in mixed areas, and two are in wealthy white neighborhoods.

He pointed to one of the latter.

That one is where my grandmother’s family lived.

The house is still standing.

Actually, it’s been converted into offices now, but the structure is original.

He sat back, processing the information.

NH might not stand for a place.

It might stand for a purpose.

Network Harbor or New Hope? [music] Something that indicated safety rather than a specific location.

Maya photographed the map with her phone, making sure to capture every detail.

We need to cross reference these locations with property records, see who owned these houses in 1900.

If we can establish a pattern, we might be able to understand how the network operated.

As they continued searching, Maya found another document, a letter dated April 1901, [music] written in elegant handwriting on stationary embossed with the initials EW.

The letter was addressed to Sister Ruth and spoke in careful coded language about packages being delivered safely and the journey north being successful for three families this season.

The letter concluded with a warning.

The opposition grows bolder.

We must exercise greater caution.

The veil protects those who wear it, but only if they trust in the pattern we have woven.

Robert read the letter twice, then looked at Maya with renewed determination.

The veil in the photograph isn’t unique.

There were multiple veils, all carrying the same information.

all serving as guides for couples who needed help.

This was more organized and more extensive than I imagined.

Robert’s grandmother’s childhood home stood on a quiet street lined with live oak trees, their branches draped with Spanish moss that swayed gently in the afternoon breeze.

The three-story building had been converted into architectural offices, but its original 1890s facade remained intact with tall windows and a wide front porch supported by elegant columns.

Maya and Robert stood across the street studying the structure.

According to the property records they had found, the house had been owned by the Thompson family from 1887 to 1952.

Robert’s grandmother, Sarah, had been born in that house in 1920.

The daughter of Elizabeth Thompson, who matched the initials ew on the letter they had found.

Her maiden name had been Williams.

“My great-g grandandmother, Elizabeth,” Robert said quietly.

“I knew she was educated, progressive for her time.

My grandmother used to say Elizabeth taught her to see people as individuals, not by the color of their skin.

I never understood the significance of that until now.

They crossed the street and entered the building.

The receptionist, a young woman with bright red hair, looked up from her desk with a professional smile.

Robert explained that he was researching his family history and asked if they might be allowed to see the building’s original features, particularly any preserved structures from the early 1900s.

The receptionist made a quick phone call, and within minutes, the office manager appeared, an enthusiastic man in his 40s named David, who loved the building’s history.

The main structure is all original, he said, leading them through the hallways.

We’ve kept as much as possible intact.

The basement still has the original stone foundation, and there’s actually a sealed room down there that we’ve never opened.

The previous owner said it was just old storage.

Ma and Robert exchanged glances.

Could we see the basement? Mia asked.

David led them down a narrow staircase into a cool, dimly lit space that smelled of earth and old wood.

The basement had been partially renovated into storage for office supplies, but in the far corner, behind a set of metal shelving units, they could see an old wooden door, its surface marked with layers of paint from different eras.

That’s the sealed room, David said.

We were told the lock was rusted shut and the keys were lost decades ago.

We’ve never had a reason to force it open.

[music] Robert looked at Maya, then at David.

Would you allow us to try? I believe this room might contain family documents related to my research.

David hesitated, then shrugged.

Sure, why not? [music] Just be careful.

The building is structurally sound, but who knows what’s been sitting in there for a century.

Robert pulled out his phone and called a locksmith he knew, explaining the situation.

Within 40 minutes, a woman named Patricia arrived with her tools.

She examined the old lock, corroded and stiff with age, and began working on it with practiced patience.

The lock resisted at first, but Patricia was skilled.

After 15 minutes of careful manipulation, they heard a decisive click.

The door, swollen with moisture and time, required Robert and David’s combined strength to push open, its hinges groaning in protest.

Inside was a small room, perhaps 10 ft x 12, with stone walls and a low ceiling.

Wooden shelves lined one wall, and in the dim light from the doorway, they could see boxes, old fabric bundles, and what looked like stacks of papers wrapped in oil cloth.

Maya stepped inside carefully, her phone’s flashlight illuminating the space.

On the nearest shelf sat three large wooden boxes.

She opened the first one, her heart pounding, and found inside something extraordinary.

More veils, at least a dozen of them, each one carefully folded and wrapped in tissue paper, each one bearing tiny embroidered messages along their edges.

Maya and Robert spent the next several hours carefully cataloging the contents of the sealed room.

David had given them permission to document everything, his own curiosity now thoroughly peaked.

They worked methodically, photographing each item before examining it, treating every artifact with the reverence it deserved.

The veils were the most striking discovery.

Each one was unique in its lace pattern and embroidery style, but all carried the same type of hidden messages, addresses, instructions, and what appeared to be names or codes.

Some were in better condition than others, but even the most fragile had been carefully preserved, wrapped in protective layers that had kept them safe from moisture and decay for over a century.

Beneath the boxes of veils, they found journals.

Five leatherbound books filled with meticulous handwriting, dated from 1897 to 1906.

The first entry Maya read made her breath catch in her throat.

March 14th, 1897.

Today marks the beginning of our work.

God has called us to help those whom society would tear apart.

Love should not be constrained by man’s laws when those laws contradict God’s greater commandment.

We have secured safe passage for the first couple, James and Ruth, who will marry in Philadelphia next month.

The veil I created for Ruth carries all the information they will need to return home safely and contact us if they face danger.

May God protect them.

The entries continued in similar fashion, each one documenting a couple helped by the network.

The journal keeper, who signed entries as EW, Elizabeth Williams, recorded not just names and dates, but also the challenges faced, threatening letters, surveillance by suspicious neighbors.

One terrifying incident where a couple was nearly discovered by a hostile mob.

Robert sat on an old wooden crate reading through the journals with tears streaming down his face.

My great-grandmother did this.

She risked everything.

If she had been caught, she could have been killed and my entire family would have been destroyed.

Maya found a box containing letters, hundreds of them, organized by year.

They were thank you notes from couples who had been helped, [music] updates on their lives, birth announcements for children who existed because the network had made their parents’ union possible.

One letter dated 1903 [music] was particularly moving.

Dear Mrs.

Williams, you will never know the depth of our gratitude.

Thomas and I have been married 2 years now, and we have a daughter, Grace.

We live quietly, but we live without fear because of the protection your network provided.

The veil you gave me hangs in our bedroom, a reminder of the kindness of strangers who became family.

We pray for you always.

Among the documents, Maya discovered detailed maps of escape routes, lists of sympathetic ministers in northern cities, and even financial records showing money that had been discreetly provided to help couples establish themselves after marriage.

The network wasn’t just about getting people married.

It was about helping them survive afterward.

One journal entry from 1902 stood out.

The opposition has identified some of our safe houses.

We must adapt.

I have begun training Ruth Harrison, a young seamstress, in the art of creating the veils.

She is trustworthy and shares our conviction.

If anything happens to me, the work must continue.

Robert looked up at Maya.

Ruth Harrison.

That might be the bride in the photograph.

If she was trained to make the veils, then she was part of the network’s leadership.

Mia pulled out her phone and compared the photograph they had been restoring with the descriptions in the journals.

In an entry from September 1900, Elizabeth Williams wrote, “Ruth married her beloved John today in a ceremony in Boston.

She wore the veil with pride, knowing its true meaning.

They return to Charleston tomorrow.

May God grant them peace.

” Finding Ruth Harrison’s descendants took three days of intensive research.

Robert utilized his university connections, accessing genealological databases and census records, while Maya continued restoring the wedding photograph, now understanding the profound significance of every detail she was preserving.

The trail led them to a woman named Dorothy Harris, aged 78, who lived in a modest home in North Charleston.

She was Ruth Harrison’s great-granddaughter, a retired school teacher who greeted them at her door with cautious warmth when they called ahead and explained their purpose.

Dorothy’s living room was filled with family photographs spanning multiple generations, covering the walls in a visual timeline of black American history.

She served them sweet tea and homemade pound cake as they sat on her comfortable sofa, the afternoon light streaming through lace curtains remarkably similar to those in the veils they [music] had found.

I always knew there was something special about my great-g grandandmother,” Dorothy said, her voice carrying the soft rhythms of the Carolina Low Country.

But the family never spoke about it directly.

There was always this sense that her story was dangerous somehow, even decades after her death.

Maya showed her the restored photograph on her laptop, and Dorothy’s eyes filled with tears immediately.

I’ve never seen this.

[music] I’ve heard about it, but I’ve never seen their faces.

She traced the screen gently with one finger.

That’s Ruth and John, my great-grandparents.

They were together for 52 years before John passed in 1952.

[music] Ruth lived until 1959.

Robert opened his folder of documents.

Dorothy, we found journals that suggest Ruth was part of a network helping interracial couples marry.

Does your family know anything about this? Dorothy was quiet for a long moment, her hands folded in her lap.

[music] Finally, she stood and walked to an old secretary desk in the corner.

She pulled out a key from a chain around her neck and unlocked a small drawer.

From it she withdrew a faded blue envelope, its edges worn soft with age.

My grandmother gave this to me before [music] she died.

She said I would know when it was time to open it.

I think that time is now.

Inside the envelope was a letter written in careful cursive on yellowed paper.

Dorothy read it aloud, her voice steadied despite the emotion evident on her face.

To my descendants who read this, “My mother Ruth was a brave woman who believed that love transcended the boundaries men created.

She and my father John married when such unions were considered criminal by the state and immoral by society.

But they loved each other and they built a good life together despite the hatred and danger they faced.

My mother did more than survive her own struggle.

She helped others.

She sewed veils for brides who needed to know they were not alone, that there were people who would help them, protect them, guide them to safety.

She did this work for 17 years until her hands became too arthritic to do the fine embroidery required.

She never spoke of it openly, even to me, except once near the end of her life.

She told me that the veils were her greatest achievement, greater than any of the beautiful dresses she made for wealthy clients, greater than any recognition she received for her sewing skills.

The veils, she said, were woven with hope, and hope, she believed, was the strongest thread of all.

The room was silent, except for the ticking of an old clock on the mantle.

Dorothy carefully refolded the letter and placed it back in its envelope.

My great-grandmother kept a box in her sewing room.

After she died, my grandmother inherited it and then my mother and then me.

I’ve never opened it.

I was told to keep it sealed until someone came asking the right questions.

I think you’ve just asked them.

The wooden sewing box was smaller than my expected, perhaps 18 in long and a foot wide, made of dark walnut with brass hinges that had tarnished to a deep green.

Dorothy placed it on her dining room table with careful reverence, treating it as the precious artifact it clearly was.

I’ve carried this box through three different homes,” Dorothy said softly.

“I’ve kept it safe, even when I didn’t fully understand why.

My mother made me promise, and she made me understand that some promises are sacred.

” The box’s lid was sealed with old wax, brittle and cracked with age, but still intact.

Robert carefully broke the seal with a butter knife Dorothy provided, working slowly to preserve as much as possible.

When the lid finally lifted, they were greeted by the scent of aged fabric and dried lavender.

Inside, nestled in tissue paper, were the tools of Ruth’s trade.

Silver scissors, still sharp despite the decades, spools of thread in every color imaginable, some so old the thread had begun to separate, a pin cushion shaped like a tomato, faded but intact, and beneath it all a small leather journal.

Maya lifted the journal carefully.

Its cover was worn smooth from handling, and when she opened it, she found pages filled with sketches [music] and notes.

These were Ruth’s designs for the veils.

Each one drawn in careful detail with annotations about which symbols meant what, which [music] patterns indicated which safe houses, which embroidery stitches carried which coded messages.

She created a whole language, Maya whispered, turning the pages.

Each design element means something specific.

This curl pattern means travel by night.

This flower indicates a safe house with a sympathetic doctor.

This particular lace style means knock three times, ask for Sarah.

Robert photographed each page, documenting the intricate system Ruth had developed.

It was brilliant in its simplicity.

Anyone examining the veils would see only beautiful, if unusual, embroidery, but those who knew the code could read detailed instructions for survival.

One page showed the design for what was clearly the veil in the photograph they had been restoring.

Ruth had written beside it, my own veil, completed August 1900, contains a complete network guide in case we must pass it to others who take our place.

Northstar Church remains the hub.

Trust in the pattern.

Beneath the journal, they found something else.

Photographs.

Not old wedding pictures, but modern Polaroids from the 1950s showing elderly Ruth surrounded by younger people, both black and white.

Several generations gathered together.

On the back of one photo in shaky handwriting, someone had written, “The families together at last, 1958.

” Dorothy picked up the photograph, studying it closely.

“I’m in this picture.

I was maybe 8 years old.

I remember that day, but I didn’t understand what it meant.

All these people came to our house, people of different races, which was still unusual in 1958.

They all wanted to meet Ruth to thank her for something I didn’t understand.

She was very old then and very frail, but she smiled all day.

She pointed to different faces in the photograph.

That woman there, she was white, married to a black man.

Those two in the back, they were a black woman and a white man.

That young couple on the left, they looked Asian-American and white.

All of them from different generations, all connected somehow to my great-grandmother’s work.

Robert’s voice was thick with emotion.

She didn’t just help people in her own time.

She created something that lasted, that people remembered and honored decades later.

That’s extraordinary.

At the very bottom of the box, wrapped in a piece of silk, they found one final veil.

Unlike the others, this one was pristine, never worn, its white fabric still bright, its embroidery fresh and perfect.

[music] Pinned to it was a small note in Ruth’s handwriting.

For the last bride who needs it, may you never need it at all.

Maya stood in front of the Charleston County Historical Society’s board of directors, her laptop connected to a projector displaying the restored wedding photograph.

Beside her sat Robert, Dorothy, and three other descendants of people helped by Ruth’s network, whom they had located through intensive research over the past two weeks.

The presentation had taken a month to prepare.

They had documented everything, the journals, the veils, the maps, the letters, and the oral histories collected from descendants.

Maya had spent countless hours restoring not just the original wedding photograph, but also images from the Polaroid Dorothy had shared, creating a visual timeline of the network’s impact across generations.

The board members, a diverse group of historians and community leaders, sat in wrapped attention as Maya concluded her presentation.

What we’ve discovered is not just a story about individual courage, though there is certainly that.

This is evidence of an organized resistance to unjust laws, a network that operated for decades, helping an unknown number of couples exercise their fundamental right to marry the person they loved.

She advanced to the final slide, showing the restored photograph in all its clarity.

The bride’s face was now fully visible.

Her expression serene and determined.

The veil’s hidden messages, though invisible in the photograph itself, were now understood and documented.

Ruth Harrison and John Watts married on September 15th, 1900 in Boston.

They returned to Charleston and lived here for the rest of their lives.

But their story is just one thread in a larger tapestry of resistance and love.

Dr.

Jennifer Mitchell, the historical society’s director, leaned forward.

What you’re proposing is a significant exhibition.

It would require resources, space, and careful curation.

But more than that, it would require us to tell a story that many people in this city might find uncomfortable.

Dorothy stood up, her posture straight despite her age.

My great-g grandandmother lived with discomfort every day of her life.

She risked everything because she believed some truths were more important than comfort.

I think we owe it to her and to all the people she helped to tell the story honestly.

Another board member, an older white man named Thomas, spoke up.

I appreciate the historical significance, but we need to consider the implications.

Some of the families involved may not want this public attention.

Some of the safe houses you’ve identified are still standing, still owned by descendants of the people who harbored these couples.

Robert nodded.

We’ve been sensitive to that.

We’ve contacted every living descendant we could find.

Some prefer to remain anonymous and we’ve respected that.

But others, like Dorothy, want the story told.

They want their ancestors honored.

The discussion continued for another hour with questions about authenticity, historical context, and the potential impact on the community.

Finally, Dr.

Mitchell called for a vote.

The board approved the exhibition unanimously with the caveat that all ethical considerations be carefully maintained and that descendants have final approval over how their family’s stories are told.

As they left the meeting, Mia felt both exhilarated and exhausted.

The exhibition would open in six months, giving them time to prepare a comprehensive display that would honor Ruth’s work and the network she had helped create.

[music] That evening, sitting in Dorothy’s living room once again, they toasted with sweet tea to Ruth’s legacy.

Dorothy held up the restored photograph, now professionally printed and framed.

“She would be proud,” Dorothy said softly.

“Not because of the recognition, but because the truth is finally being told.

Because love won.

” The exhibition opened on a warm October morning, almost exactly 124 years after Ruth and John’s wedding.

The Historical Society’s main gallery had been transformed.

Its walls covered with photographs, documents, and carefully preserved artifacts from the network.

At the center of the room, displayed in a climate controlled case, hung Ruth’s wedding veil, restored to its original beauty, with detailed explanations of the hidden messages it contained.

Maya arrived early before the doors opened to the public.

She walked through the exhibition slowly, reviewing every panel, every photograph, every artifact.

The story was told chronologically, beginning with the social and legal context of the early 1900s, explaining the laws that made interracial marriage illegal across much of the South, the violence and intimidation that enforced those laws.

Then came the heart of the exhibition, the network itself.

Large panels displayed excerpts from Elizabeth Williams journals, Ruth’s design notebooks, and the thank you letters from couples who had been helped.

Photographs of the safe houses then and now showed the physical spaces where this dangerous work had been carried out.

Interactive displays allowed visitors to learn about the coding system used in the veils to understand how information was hidden in plain sight.

One wall was dedicated to the couples themselves.

Through research, they had identified 23 couples who had been helped by the network between 1897 and 1914 when the work apparently ended, possibly due to increasing danger or the deaths of key organizers.

Each couple had a small photograph or description, and where possible, updates on their lives.

Children born, businesses established, quiet lives lived despite the hostility around them.

Dorothy arrived with a group of about 30 people, descendants of various couples helped by the network.

They had come from across the country for the opening from Boston, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, places where some couples had fled permanently, unable to return to the south, even with the network’s protection.

As the doors opened and visitors began streaming in, Maya watched their reactions.

Some people wept openly, particularly when reading the letters from grateful couples.

Others stood in silence before the display of veils, understanding the courage required to create and wear them.

Young people asked questions, their faces reflecting amazement that such recent history had been so completely hidden.

A local news crew had come to cover the opening.

The reporter, a young black woman named Jessica, interviewed Dorothy on camera.

What does it mean to you to see your great-g grandandmother’s work recognized this way? Dorothy’s voice was steady and clear.

It means that love wins eventually.

It means that the people who tried to keep others apart through laws and violence and hate, they didn’t succeed.

Ruth and John and all the couples like them, they live their lives.

They raised their families.

And now, more than a century later, we’re all here together living proof that their courage mattered.

Robert stood beside Maya as they watched the crowd move through the exhibition.

[music] “You know what strikes me most?” he said.

the ordinariness of it all.

These were regular people, not famous activists or wealthy philanthropists, just people who saw injustice and decided to do something about it, knowing they could lose everything.

Maya nodded, thinking about the months of work that had brought them to this moment.

And they did it through something so simple.

Thread and fabric turned into tools of resistance.

As the afternoon wore on, Maya noticed one visitor who stood for a long time before the display of Ruth and John’s wedding photograph.

[music] She was an elderly white woman, perhaps in her 80s, using a walker.

Ma approached her gently.

[music] “That photograph is special to you?” Ma asked.

The woman turned, her eyes bright with tears.

“My grandmother told me stories about a black seamstress who made her wedding veil in 1904.

My grandmother married my grandfather who was black and they had to leave South Carolina.

They never came back.

But my grandmother kept that veil her whole life, and she always said it saved their lives, though she never explained how.

I inherited it when she died, and I’ve kept it safe, even though I didn’t understand [music] its significance.

” She gestured to the exhibition.

Until now.

She opened her purse and pulled out a photograph of her own showing a young interracial couple from the early 1900s.

That’s them.

I wonder if their story is here somewhere.

Maya took the photograph carefully.

Would you be willing to share it with us to add to the archive we’re building? The woman nodded.

Yes.

Yes, I would.

It’s time these stories were told.

All of them.

Ah, as the sun set and the exhibition’s first day drew to a close, Mia stood once more before Ruth’s wedding photograph, now restored to clarity and given its proper context, the bride and groom gazed out at her across 124 years.

Their faces serene, their courage immortalized, not just in the image, but in the legacy they had created.

The hidden message in the veil had been revealed at last.

But Maya understood now that the true message was never really hidden at all.

It was woven into every thread, visible to anyone willing to look closely enough.

Love persists.

Hope endures.

News

🚛 HIGHWAY CHAOS — TRUCKERS’ REVOLT PARALYZES EVERY LAND ROUTE, KHAMENEI SCRAMBLES TO CONTAIN THE FURY 🌪️ The narrator’s voice drops to a biting whisper as convoys snake through empty highways, fuel depots go silent, and leaders in Tehran realize this isn’t just a protest — it’s a nationwide blockade that could topple power and ignite panic across the region 👇

The Reckoning of the Highways: A Nation on the Edge In the heart of Tehran, the air was thick with…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Darkened City: A Night of Reckoning In the heart of Moscow, a city that once stood proud and unyielding,…

🎬 MEL GIBSON DROPS THE BOMBSHELL — “THE RESURRECTION” CAST REVEALED IN A MIDNIGHT MEETING THAT LEFT HOLLYWOOD GASPING 😱 The narrator hisses with delicious suspense as studio doors slam shut, contracts slide across tables, and familiar faces emerge from the shadows, each name more explosive than the last, turning what should’ve been a simple casting call into a cloak-and-dagger spectacle worthy of a conspiracy thriller 👇

The Shocking Resurrection: A Hollywood Revelation In a world where faith intertwines with fame, the announcement sent ripples through the…

🎬 “TO THIS DAY, NO ONE CAN EXPLAIN IT” — JIM CAVIEZEL BREAKS YEARS OF SILENCE ABOUT THE MYSTERY THAT HAUNTED HIM AFTER FILMING ⚡ In a hushed, almost trembling confession, the actor leans back and stares past the lights, hinting at strange accidents, eerie coincidences, and moments on set that felt less like cinema and more like something watching from the shadows, leaving even hardened crew members shaken to their core 👇

The Unseen Shadows: Jim Caviezel’s Revelation In the dim light of a secluded room, Jim Caviezel sat across from the…

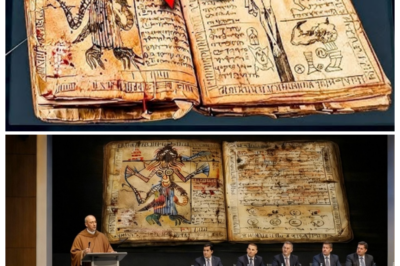

📜 SEALED FOR CENTURIES — ETHIOPIAN MONKS FINALLY RELEASE A TRANSLATED RESURRECTION PASSAGE, AND SCHOLARS SAY “NOTHING WILL BE THE SAME” ⛪ The narrator’s voice drops to a breathless whisper as ancient parchment cracks open under candlelight, hooded figures guard the doors, and words once locked inside stone monasteries spill out, threatening to shake faith, history, and everything believers thought they understood 👇

The Unveiling of Truth: A Resurrection of Belief In the heart of Ethiopia, where the ancient echoes of faith intertwine…

🕯️ FINAL CONFESSION — BEFORE HE DIES, MEL GIBSON CLAIMS TO REVEAL JESUS’ “MISSING WORDS,” AND BELIEVERS ARE STUNNED INTO SILENCE 📜 The narrator’s voice drops to a hushed, dramatic whisper as old notebooks open, candlelight flickers across ancient pages, and Gibson hints that lines never recorded in scripture could rewrite everything the faithful thought they knew 👇

The Unveiling of Hidden Truths In the dim light of his private study, Mel Gibson sat surrounded by piles of…

End of content

No more pages to load