Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time at which you’re listening to this narration.

We’re interested in knowing to which places and at what times of day or night these documented stories reach.

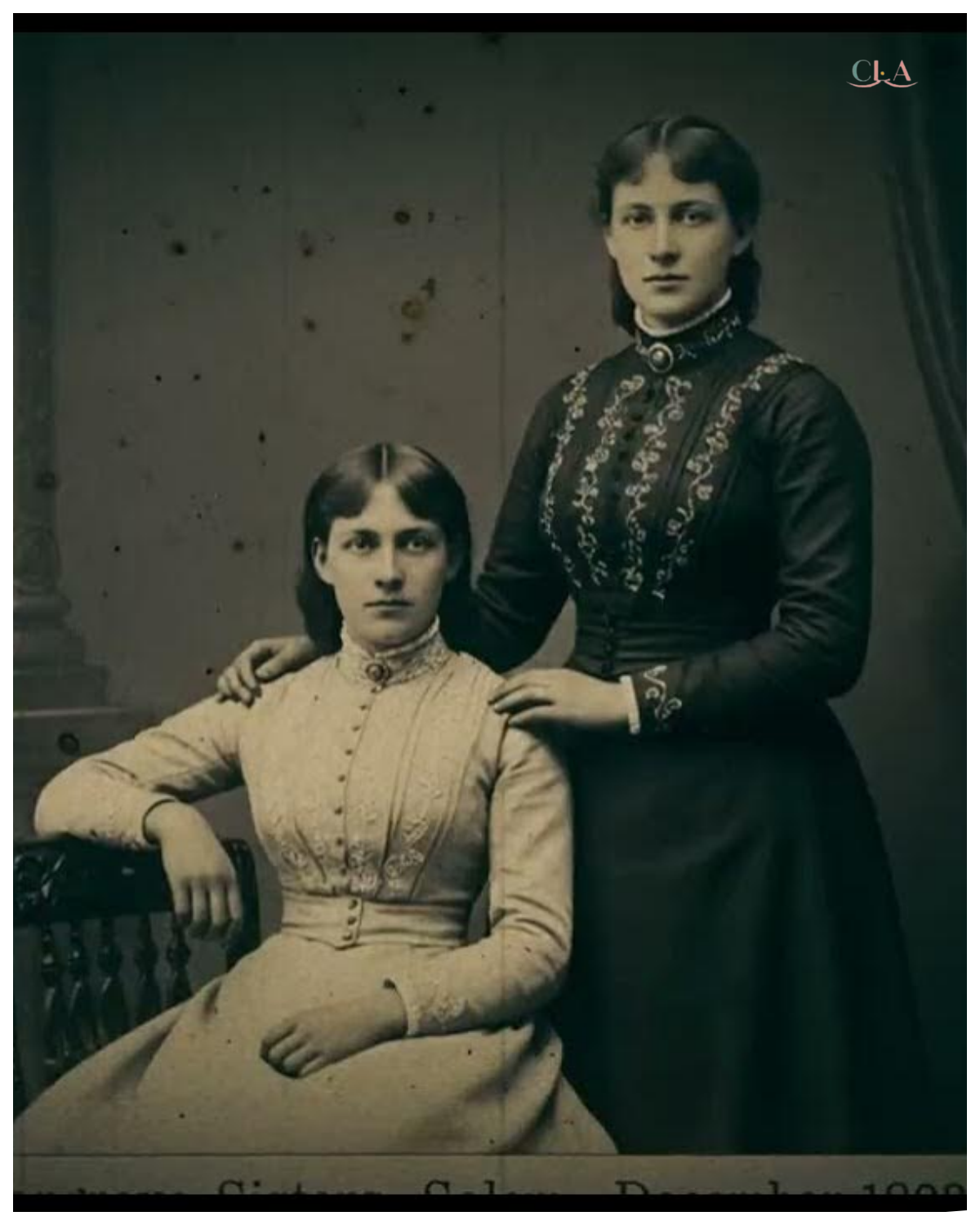

The winter of 1894 brought with it more than just the usual frigid winds to Salem, Massachusetts.

It marked the beginning of what would become one of the most perplexing and disquing mysteries in the region’s history.

The Hard Grove estate, a once admired Victorian mansion on the outskirts of town, stood as a testament to family wealth and respectability.

Yet by spring of that same year, the name Hargroveve would be spoken only in hushed tones among the town’s people, if spoken of at all.

Elellanar and Margaret Hargrove, unmarried sisters in their 30s, were considered peculiar but respected members of Salem society.

Their father, Thaddius Hargrove, had amassed considerable wealth in the textile industry before his passing in 1886, leaving the sisters to maintain the family’s social standing.

They were known for their charitable donations to the town’s church and their impeccable manners, though few could claim to know them intimately.

What makes this case particularly unusual is not just the nature of what transpired, but how thoroughly the events were subsequently erased from official records.

According to what limited documentation remains, primarily in the form of personal correspondents and newspaper clippings preserved by the Historical Society of Essex County, the Harrove case was deliberately struck from public memory through a systematic removal of evidence.

One detail consistently appears in the scattered accounts.

the attic of the Harrove mansion, a room that, according to the architectural plans filed with the county in 1871, shouldn’t have existed at all.

Dr.

James Sullivan, a local physician with a practice on Essex Street, noted in his personal journal an unusual increase in house calls to the Harrove estate beginning in December of 1893.

His entries, discovered decades later in a collection of medical ephemerra, make particular mention of Margaret Hargro’s nervous disposition and increasing preoccupation with noises from the upper floor.

Sullivan prescribed various tonics and recommended rest, attributing her condition to female hysteria, a common diagnosis of that era.

What’s peculiar is that by February of 1894, Dr.

Sullivan’s regular visits abruptly ceased.

When questioned by colleagues about the Harrove sisters, he would reportedly change the subject or claim patient confidentiality.

Several sources suggest he refused to return to the house after his final visit on February 23rd.

The Hardgrove estate sat on 3 acres of land, partially wooded with a small servants house and carriage barn behind the main structure.

The house itself was a three-story Victorian with a distinctive northeastern turret and wraparound porch.

Census records indicate that apart from the sisters, the household included a cook, a maid, and a groundskeeper, all of whom would later provide conflicting accounts of what occurred within those walls.

Martha Winters, the cook who had served the family for over 15 years, abruptly left her position in March of 1894.

The Hargrove place keeps them best of all.

What we do know with certainty is that on the morning of April 7th, 1894, Eleanor Hargrove appeared at the Salem Police Station in a state described by officer William Brody as severe agitation.

The official police report, one of the few documents to survive the subsequent purge, states that Miss Hargrove requested assistance at her home regarding her sister Margaret, who she claimed was no longer herself.

When officers arrived at the estate, they found the front door a jar and the house unnaturally silent.

When interviewed by the Salem Gazette for an unrelated story in 1900, she refused to discuss her former employers, saying only, “Some houses keep their secrets better than others.

” According to Officer Brody’s personal account, recovered from his grandson’s attic in 1958.

The officers called out upon entering, but received no response.

They found Elellanar Harrove seated in the parlor, staring blankly at the wall, apparently unable or unwilling to guide them further.

The subsequent search of the house revealed Margaret Hargrove in the master bedroom on the second floor.

Officer Brody described her as perfectly composed, seated at her vanity, arranging her hair as if preparing for a social engagement.

When questioned about her sister’s concerns, Margaret reportedly smiled and said, “Ellaner has always been prone to flights of fancy.

There is nothing a miss here.

” The officers, finding no evidence of disturbance or crime, had no choice but to leave the premises.

” They noted in their report that Eleanor seemed disappointed but not surprised by this outcome.

As they departed, Officer Brody recalled Elellanar whispering, “She won’t let you see the attic.

she never does.

The following week saw an unusual amount of activity at the Hard Grove estate.

Deliveries of lumber and other building materials were observed and a carpenter from Danvers was hired for what neighbors were told was routine maintenance.

Frederick Jenkins, the groundskeeper, later told his wife, according to her diary discovered in 1912, that he had been instructed to deny all visitors access to the property during this period.

On April 22nd, smoke was observed rising from the chimney of the Harrove Mansion, unusual for that time of year.

A neighbor, Mrs.

Catherine Lloyd reported to her sister in a letter that she had never smelled such an acrid odor and that it had permeated her laundry hanging nearby.

She wrote, “It was not the smell of burning wood or coal, but something altogether different, something I dare not name.

” By the end of April, both Harg Grove sisters had resumed their normal activities in town.

They attended church, made their usual rounds of social calls, and even hosted a small gathering for the Ladies Aid Society.

Those who interacted with them noted nothing unusual, say perhaps that they seemed more alike than ever before.

As one attendee later recalled, “It was Reverend Thomas Blackwood who first raised concerns about the sister’s well-being.

In his journal, he wrote of a confession Ellaner had made during a private meeting on May 3rd.

The exact nature of this confession was not recorded, but Reverend Blackwood noted that he had advised her to seek help beyond spiritual guidance and that he had grave concerns about the influence of the house upon both sisters.

3 days later, Reverend Blackwood requested that the town doctor accompany him to the Harrove estate for what he described as a wellness visit.

They were received politely, but were not permitted beyond the foyer.

Margaret assured them that both she and Elellanor were in excellent health and that the reverend had misunderstood her sister’s concerns.

As they left, Reverend Blackwood reported hearing a sound like distant weeping coming from the upper floors of the house.

When he mentioned this to Margaret, she smiled and said, “The wind plays strange tricks in old houses, Reverend.

” The first week of May brought unusually heavy rains to Salem.

On the night of May 7th, during a particularly violent thunderstorm, neighbors reported hearing terrible cries from the direction of the Harrove estate.

Albert Preston, whose farm bordered the Harrove property, later testified that he had seen a figure in white moving about the uppermost window of the house, a window that, according to the architectural plans, should have been part of an unfinished storage space, not a habitable room.

Preston, concerned by what he had witnessed, attempted to visit the estate the following morning, but was turned away by the groundskeeper, who claimed the sisters were not receiving visitors due to illness.

Unsatisfied with this explanation, Preston reported his concerns to the police.

Officer Brody, accompanied by the town’s newly appointed health inspector, called at the Harrove Estate on May 9th.

They were received by both sisters in the parlor and found nothing outwardly a miss.

When asked about the reported disturbance, Margaret explained that a window had been left open during the storm, causing a shutter to bang repeatedly against the house.

As for the figure in white, she suggested it might have been a curtain blown by the wind.

The health inspector requested to examine the upper floors of the house, citing concerns about potential water damage from the storm.

According to his report filed with the town clerk and later removed, his inspection revealed nothing unusual on the second floor.

When he inquired about access to the attic, Ellaner quickly interjected that the space was used only for storage and was currently inaccessible due to a damaged ladder.

The inspector noted in his report that both sisters became visibly anxious at the mention of the attic and that Margaret’s hand, which had been resting on her sister’s arm, tightened to such a degree that Elellanar winced.

Nevertheless, without cause for further investigation, the officials departed, though officer Brody later confided to a colleague that he had observed what appeared to be scratch marks on the inside of the parlor door, marks consistent with fingernails, as if someone had been desperately trying to claw their way out.

By miday, rumors had begun to circulate through Salem regarding the Harrove sisters.

Some suggested that Elellanar was suffering from the same nervous condition that had allegedly claimed their mother, who had spent her final years in an asylum in Boston.

Others whispered of strange deliveries to the house in the dead of night.

Medical supplies, according to the local pharmacist’s son, who claimed to have seen the packages.

The pharmacist in question, Harold Merritt, maintained a small shop on Essex Street where he prepared medicinal compounds for the town’s physicians.

According to his business ledger preserved by his descendants and made available to researchers in 1946, the Harrove household placed several unusual orders during this period.

These included significant quantities of ludinum, chloral hydrate, and other sedatives typically prescribed for severe insomnia or agitation.

Most notable was an order placed on May 21st for materials more commonly associated with a hospital setting, bandages, surgical spirits, and a quantity of plaster of Paris sufficient to create a full body cast.

When questioned about these purchases by Dr.

Sullivan Margaret reportedly explained that they were preparing a care package for a cousin who had suffered injuries in a railway accident in Connecticut.

No record of such an accident exists in newspaper accounts from the period, nor do family records indicate the existence of cousins in Connecticut.

This discrepancy was not noted at the time, but emerged years later during the collation of dispersed documents related to the case.

It was during this period that Elellanar Harrove stopped appearing in public altogether.

Margaret explained her sister’s absence as the result of a persistent illness requiring rest and seclusion.

She continued to attend social functions alone, maintaining the family’s presence in Salem society with remarkable composure.

Gertrude Hathaway, who served as the Harro’s maid during this time, later told her daughter, as recorded in the daughter’s memoirs, published in 1928, that she had been expressly forbidden from entering Eleanor’s bedroom to clean or deliver meals.

Miss Margaret said her sister was extremely sensitive to disturbances and required absolute quiet, Hathaway recalled.

All meals and necessities were to be left outside the door, and I was never to knock or attempt to speak with Miss Elellanar directly.

Haway also noted a curious ritual that began in late May.

Every evening at precisely 8:00, Margaret would ascend the stairs carrying a tray with tea and a small decanter that smelled strongly of medication.

She would disappear for approximately 1 hour before returning with the tray, often bearing untouched food, but always with an empty decanter.

On June 2nd, a fire broke out in the servants’s quarters behind the main house.

While the blaze was quickly contained and caused minimal damage, it brought the fire brigade onto the property.

Thomas Collins, a volunteer firefighter, reported seeing movement in the highest window of the house while the brigade was packing up their equipment.

When he pointed this out to Margaret Hargrove, she reportedly stared at the window for a long moment before stating, “That’s impossible.

No one is up there.

” Collins later told his fellow firefighters that he had distinctly seen a pale face pressed against the glass, though he admitted the distance and poor light might have confused his perception.

What he described with more certainty, however, was Margaret’s reaction.

She didn’t look surprised or confused, he said.

She looked afraid and then angry.

In the days following the fire, Hathaway observed increased activity on the third floor of the house.

In her daughter’s account, she described hearing furniture being moved about and the sound of hammering from the attic space.

When she inquired about the noise, Margaret explained that they were finally repairing the damage from a roof leak that had occurred the previous winter.

The following Sunday, Margaret Hargrove attended church alone again.

After the service, she engaged Reverend Blackwood in conversation, informing him that Elellanar had taken a turn for the worse and requesting that he call at the house to provide spiritual comfort.

The Reverend agreed to visit that afternoon.

What transpired during Reverend Blackwood’s visit on June 5th remains largely unknown.

He never spoke publicly about what he witnessed inside the Horror Grove home.

His journal entries for the week following the visit are conspicuously missing, torn from the book.

The next intact entry, dated June 12th, contains only the cryptic statement, “Some sins cannot be absolved through confession alone.

Some require more permanent measures.

” Church records indicate that on June 6th, Reverend Blackwood requested an emergency meeting with the town’s selectmen.

The minutes of this meeting were later removed from the town archives, but a letter from one of the selectmen to his brother in Boston, preserved in family papers, mentions a disturbing account given by the reverend regarding the Hargrove household and a decision to investigate discreetly given the family’s standing in the community.

No record of any such investigation exists in town files.

However, the personal diary of Judge Henry Putnham, head selectman at the time, contains a brief entry dated June 9th.

Matter of H sisters resolved satisfactorily.

RB concerns unfounded.

Case closed by unanimous decision.

On June 15th, Margaret Hargrove announced to the Lady’s Aid Society that she and Elellanar would be traveling to Europe for an extended stay, hoping that the change of climate would benefit her sister’s health.

She indicated they would depart within the week and had arranged for the house to be maintained in their absence.

What makes this announcement particularly suspicious is the discovery made years later of passenger manifests from all ships departing Boston for European ports during the summer of 1894.

Neither Eleanor nor Margaret Hargrove appears on any of these lists.

Even more curious is a discovery made in 1917 when renovations to a Boston hotel revealed a trunk hidden in a sealed wall cavity.

The trunk contained women’s clothing from the 1890s, including several dresses with the initials EH embroidered on the collars.

Also found were train tickets to Montreal, dated June 16th, 1894 in the name of M.

Harrington.

The Harrove estate remained occupied, however.

Lights were seen in the windows at night, and smoke occasionally rose from the chimneys.

Frederick Jenkins, the groundskeeper, continued to maintain the property, though he now firmly refused all visitors.

When pressed by neighbors, he would only say that the sisters had left instructions that the house be kept ready for their return at any moment.

Jenkins’s wife, Mary, who occasionally assisted with household duties at the estate, later told her sister, as recorded in a letter dated August 1894, that she had heard strange sounds coming from the upper floors of the house at night, like someone pacing back and forth, she wrote, and sometimes what sounds like two women talking, though one voice seems weaker than the other.

Mary Jenkins also reported an unsettling discovery she had made while cleaning.

In a rarely used parlor at the back of the house, she found a mirror with what appeared to be practice sentences written on it in soap.

My name is Elellanar Hargrove, and I have always lived in Salem, repeated multiple times, each iteration slightly different in handwriting.

When she mentioned this curious find to her husband, he reportedly became agitated and warned her never to speak of it to anyone.

He told me that Miss Margaret had developed an interest in handwriting analysis, Mary wrote.

But his face went so pale when he said it that I knew he was lying.

In October of 1894, a traveling salesman passing through Salem reported a strange encounter.

Having lost his way after dark, he approached the Harrove estate to ask for directions.

He claimed that as he neared the house, he saw a woman’s face at an upper window, her mouth open in what appeared to be a silent scream.

When he reached the front door and knocked, he was greeted by a woman who introduced herself as Margaret Hargrove.

The salesman, finding this odd given the rumors of the sister’s departure, inquired whether they had returned from Europe.

According to his account published in a Boston newspaper in 1900, the woman smiled strangely and replied, “I am always here.

It is Ellaner who comes and goes.

” When he mentioned the face he had seen at the window, she invited him inside for tea, insisting there was no one else in the house.

The salesman, increasingly uneasy, declined and hastily departed.

As he glanced back at the house from the road, he claimed to see two identical female figures standing in the entrance hall watching him leave.

This account might be dismissed as the fabrication of a man seeking attention were it not for a similar experience reported by Dr.

Sullivan’s replacement, Dr.

Edward Pierce.

Called to the Harg Grove estate in November of 1894 to treat what the housekeeper described as a fall, Pierce found Margaret Hargrove alone in the parlor, apparently uninjured.

When he inquired about the patient requiring treatment, Margaret led him to a bedroom on the second floor.

According to a letter Pierce wrote to a medical colleague in Boston preserved in the colleague’s personal papers, the room contained a woman lying in bed, her face turned to the wall.

Mrs.

Jenkins gave me to understand that Miss Elellanar had taken a fall, Pice wrote.

But the figure in the bed made no movement nor sound as I entered.

When I attempted to examine her, Miss Margaret intercepted me, saying that her sister was sleeping and should not be disturbed.

She then proceeded to describe symptoms, bruising, and pain in the rib cage with such precision that I found myself writing a prescription without having examined the patient at all.

It was only as I was leaving that I realized the strangeness of what had transpired.

Pierce concluded his letter by noting that as he descended the stairs, he glanced back to see Margaret standing on the landing, whispering intensely to someone just out of sight.

I cannot shake the feeling, he wrote, that I was deliberately prevented from confirming the identity of the woman in that bed, if indeed there was a woman there at all.

Dr.

Bad air Pierce’s suspicions were apparently sufficient to prompt a second visit to the Hargrove estate the following day, ostensibly to deliver medication.

On this occasion, he was met at the door by Elellanar Hargrove, who appeared in good health and claimed no knowledge of any fall or injury.

When PICE mentioned speaking with Margaret the previous day, Elellanar’s expression reportedly changed.

She looked at me with what I can only describe as momentary panic, PICE wrote before composing herself and saying, “My sister is confused at times.

She worries unnecessarily about my health.

” When I asked to speak with Margaret directly, Eleanor informed me that she had gone to Boston for the day.

As our conversation concluded, I heard what sounded like footsteps on the floor above, though Eleanor insisted we were alone in the house.

The winter of 1894 to 1895 was particularly harsh in Massachusetts.

Heavy snowfall isolated many homes, including the Harrove Estate.

You and Salem gave much thought to the sisters during this period, assuming they remained in Europe.

One exception was Eliza Carter, whose property shared a northern boundary with the Harrove Estate.

In a letter to her daughter dated January 1895, Carter described seeing smoke from the chimneys of the Harrove house during a blizzard.

More disturbingly, she claimed to have seen a woman’s figure in the garden one morning after a heavy snowfall, standing perfectly still among the dead rose bushes, wearing only a night dress despite the freezing temperature.

When Carter called out to the figure, it reportedly turned toward her with an expression of desperate pleading before another woman appeared from the house, wrapped a blanket around the first woman, and led her firmly back inside.

Carter, concerned by what she had witnessed, attempted to visit the house later that day, but found the gates locked and received no response to her calls.

It wasn’t until March of 1895 that Margaret Hargrove reappeared in town attending a charity function at the town hall.

She explained that they had returned from Europe earlier than expected due to poor traveling conditions and that Eleanor remained at home still recovering from her illness.

Those who encountered Margaret at this event described her as changed.

She wore her hair differently, spoke more assertively, and displayed mannerisms that some longtime acquaintances found unfamiliar.

Most striking was her response when Reverend Blackwood inquired specifically after Eleanor’s health.

According to multiple witnesses, Margaret smiled oddly and replied, “Ellanor and I understand each other perfectly now.

We are more alike than ever before.

” Reverend Blackwood, visibly disturbed by this encounter, attempted to visit the Harrove estate the following day, but was turned away by the groundskeeper.

A note in his journal reads, “I fear my earlier inaction has led to something irreversible.

” The woman who calls herself Margaret Hargrove is not the same person I knew last year.

Something fundamental has changed, but whether in her appearance or her very nature, I cannot say with certainty.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1895, Margaret Hargrove maintained a visible presence in Salem Society.

She attended all the appropriate functions, made the expected charitable contributions, and even joined the town committee, organizing the Independence Day celebrations.

If anyone thought it strange that Elellaner never appeared in public, they kept such opinions to themselves.

One persistent rumor from this period involves the discovery made by a delivery boy in August.

Bringing groceries to the Harrove kitchen door.

He reportedly glimpsed a woman locked in a pantry, her face pressed against the small window in the door.

The boy described the woman as very thin with short, unevenly cut hair and eyes that seemed too large for her face.

When he asked Mrs.

Jenkins about what he had seen.

She allegedly burst into tears and begged him never to mention it to anyone.

The boy’s mother, concerned by her son’s account, reported the incident to Officer Brody, who made a cursory inquiry at the estate, but found nothing a miss.

In his report, he noted that Margaret Hargroveve had been particularly accommodating, inviting him to inspect the entire ground floor of the house, including the pantry, which contained nothing but preserved foods.

The Harrove case might have faded into obscurity, becoming merely another tale of eccentric spinsters were it not for the events of September 18th, 1895.

On that evening, a violent thunderstorm struck Salem.

Lightning reportedly struck the Hardrove estate, causing a fire that quickly engulfed the upper floors of the house.

By the time the fire brigade arrived, the roof had partially collapsed and the blaze had spread to the second floor.

Margaret Hargrove was found in the garden soaking wet and seemingly in shock.

When asked about her sister, she reportedly laughed and said, “Ellaner is where she has always been.

” As firefighters battled the blaze, a portion of the attic floor collapsed, revealing a space that, according to several witnesses, should not have existed.

The architectural plans for the house showed no room in that location, only support beams and insulation.

What was discovered in that hidden space has been systematically removed from all official records.

The fire brigade’s report for that night is missing from the town archives.

The newspaper account of the fire omits any mention of unusual discoveries.

Even the death certificate issued afterward refers only to remains recovered from the fire with no indication of identity.

However, personal accounts collected years later tell a different story.

Thomas Collins, the same firefighter who had reported seeing a face at the highest window months earlier, confided to his son on his deathbed in 1931 that what they found in the attic of the Harrove mansion was not something that should have been possible.

According to this account, the hidden room contained evidence of long-term habitation, a bed, a chair, and various personal items.

Most disturbing was the discovery of what appeared to be two sets of women’s clothing, identical in every respect, laid out as if for inspection.

Collins described scratch marks covering the inside of the door and walls, some deep enough to have splintered the wood and drawn blood, judging by the dark stains that covered them.

Collins also claimed they found a collection of personal items arranged on a small table.

hair brushes containing different lengths of the same color hair, several pairs of gloves of slightly different sizes, and a notebook filled with handwriting exercises, the same phrase written over and over in progressively more similar styles.

The phrase, according to Collins, was, “I am Margaret Harrove.

” Most disturbing of all was Colin’s description of a mirror positioned at the foot of the bed, angled so that anyone lying there would see their own reflection.

The glass had been broken, but fragments remained in the frame.

On the wall behind where the mirror had hung, someone had scratched a message into the plaster.

She is becoming me.

Dr.

Pierce was called to the scene to examine the remains found in the debris.

His medical notes, which he kept separate from his official report, describe extensive evidence of restraint and prolonged confinement.

He also noted unusual physical anomalies that he could not readily explain, concluding only that the deceased had been subjected to conditions incompatible with normal human survival for an extended period.

In a private letter to a former medical school colleague, Pierce elaborated on his observations.

The body recovered from the attic room presented a most perplexing case.

Though severely damaged by the fire, certain features remained discernable.

The hands showed evidence of healing fractures consistent with repeated trauma, possibly self-inflicted in attempts to escape confinement.

More disturbing were the indications of deliberate alterations to the subject’s appearance.

crude attempts at surgical modification that I hesitate to describe in detail.

I am convinced that whoever this poor soul was, they had been systematically transformed both physically and psychologically over many months.

Within days of the fire, Margaret Hargrove sold the ruined property to the town for a nominal sum and departed Salem.

According to the bill of sale preserved in county records, she intended to return to England, the country from which the Harrove family had originally immigrated three generations earlier.

No record of her arrival in England has ever been found.

Most remarkable about the Harrove case is not just what happened, but how thoroughly it was subsequently erased from official memory.

Within months of the fire, town officials had the ruins demolished and the land cleared.

By 1897, a small public park occupied the site with no marker or indication of the property’s former owners.

Furthermore, a systematic removal of references to the case appears to have been undertaken.

Police reports were redacted or destroyed.

Newspaper archives from the period show signs of alteration.

Even church records normally meticulously kept have suspicious gaps coinciding with key dates in the Hargroveve timeline.

This deliberate obscuring of history might have been completely successful were it not for the personal papers, diaries, and correspondence preserved by individuals with connections to the case.

These scattered accounts discovered over decades and pieced together form the foundation of what we know about the Hargrove sisters and their mysterious attic.

In 1910, a collection of personal effects belonging to Margaret Hargrove was discovered in a Boston storage facility where they had apparently been kept since shortly after the fire.

Among these items was a journal, its final entries dated just weeks before the fire that destroyed the Harrove mansion.

The journal, now part of a private collection and rarely accessible to researchers, reportedly contains disturbing insights into Margaret’s state of mind during the final months at the estate.

According to those who have examined it, Margaret wrote extensively about her sister Ellaner, describing her as changing and becoming something new.

One frequently quoted passage reads, “Ellanar insists she hears someone moving in the attic.

” I have explained repeatedly that the sounds are merely the house settling, yet she persists in this delusion.

Last night I found her at the attic door again, listening.

When I asked what she heard, she turned to me with an expression I did not recognize and said, “She’s trying to get out, Margaret, just as I did.

” I do not know what she means by this, but her manner disturbs me greatly.

Later entries become increasingly erratic, with Margaret writing about the other Elellanar and keeping her secure.

The final entry dated September 15th, 1895, 3 days before the fire, contains only the cryptic statement, “We are the same now.

” These pages, apparently inserted rather than originally bound with the book, contain detailed notes on what is described as the transference of essence.

While much of the text uses technical or possibly coded language, certain phrases stand out with disturbing clarity.

Subject must be gradually prepared through isolation and disorientation.

Mirror exercises essential to the process and final phase requires complete submission voluntarily or induced.

A notation at the top of these pages indicates they were copied from grandfather’s red book, a reference that aligns with family records showing that Thaddius Hargro’s grandfather had been involved with certain esoteric societies during his time in England before immigrating to America in the early 19th century.

In 1912, Frederick Jenkins, the longtime groundskeeper of the Hard Grove estate, was admitted to the State Hospital in Danvers, suffering from what his doctors described as acute melancholia with paranoid features.

During his confinement, he spoke repeatedly about his former employers, telling doctors and fellow patients that there were never just two Harrove sisters and that the attic held the truth.

According to hospital records, Jenkins became particularly agitated when discussing the events of June 1894.

There is no difference between us anymore.

The journal also contains several pages of what appear to be instructions or procedures written in a different hand and on older paper.

I helped her carry the body, he reportedly said during one session.

Not dead, no, but not fully alive either.

We took her up the servant stairs to the room Miss Margaret had prepared.

I didn’t ask questions.

The Harroes had been good to me, and Miss Margaret said her sister was having one of her episodes and needed to be kept safe.

Jenkins claimed that in the months that followed, he was responsible for bringing food to the attic room and removing waste, always under Margaret’s supervision.

Sometimes I heard weeping from behind that door, he told a nurse.

Other times just whispers like someone talking to themselves.

Once I heard her say, “I am still Ellaner.

” over and over.

Miss Margaret said it was just the illness talking.

Most disturbing was Jenkins’s account of the changes he observed in both sisters over time.

Miss Elellanar, the one downstairs, I mean, she started to change.

Her voice became different.

The way she walked, the way she held her teacup, more like Miss Margaret every day.

And Miss Margaret, she seemed pleased by this.

She would correct her sometimes, saying things like, “No, Ellaner, that’s not how you’ve always done it, like she was teaching her to be herself.

” Jenkins died in the hospital in 1914, having never returned to Salem.

His personal effects included a small key labeled HA, presumably standing for Harrove Attic, though the door it might have unlocked had been destroyed years earlier.

Perhaps the most revealing document related to the case emerged in 1920 when Reverend Blackwood’s complete journals were discovered during renovations to the Salem church parsonage.

The missing pages, which the Reverend had apparently removed and hidden separately, contained his account of his final visit to the Harrove estate on June 5th, 1894.

According to this account, Blackwood was received by Margaret and led to a bedroom where Elellanar supposedly lay ill.

When he entered the room, he found it empty.

Confronting Margaret about this deception, she allegedly replied, “Ellanor is where she needs to be, where I put her.

” Alarmed by this statement, Blackwood demanded to know Eleanor’s whereabouts.

Margaret reportedly led him to the attic door, producing a key from her pocket.

As she unlocked the door, she told him, “My sister has not been herself lately.

She needed to be contained until she remembers who she truly is.

” What Blackwood claimed to have seen in the attic room haunted him for the remainder of his life.

He described a space that had been converted into a crude living quarter with a bed, chamber pot, and small table.

The windows had been boarded over from the inside, allowing only thin slivers of light to penetrate.

Most disturbing was his description of Elellanar Hargrove, whom he found sitting in a corner of the room, her appearance so altered that he initially failed to recognize her.

According to Blackwood, Ellaner’s hair had been roughly cut short, and she wore a night gown soiled from extended wear.

When she saw him, she reportedly showed no recognition, only whispering repeatedly, “She’s trying to become me.

” She practices in the mirror.

Blackwood’s account continues with his confrontation of Margaret, who allegedly explained that Eleanor had begun to exhibit dangerous tendencies and required seclusion for her own protection.

When he threatened to report this imprisonment to the authorities, Margaret’s demeanor reportedly changed entirely.

“She looked at me with such coldness,” Blackwood wrote, and said words I shall never forget.

By the time you return with help, Reverend, you will find Elellanar downstairs taking tea in the parlor, perfectly composed and bewildered by your accusations.

Who do you think they will believe? Two respected ladies of this town, or a minister known to harbor unnatural interests in the spiritual afflictions of vulnerable women? Faced with this implicit threat to his reputation and the disturbing possibility that he might not be believed, Blackwood made what he later described as the greatest moral failure of my life.

He left the Harrove estate without taking immediate action, intending to consult with town officials the following day.

By the time he returned with the police on June 6th, he found exactly what Margaret had predicted.

Elellanar seated in the parlor, perfectly groomed and apparently in good health.

She expressed confusion at the reverend’s concerns and invited the officers to inspect the house, including the attic, which was found to contain nothing but the usual household storage.

Blackwood’s journal entry concludes with a haunting observation.

As I left in humiliation, Elellanar took my hand and whispered something that chills me still.

I am not who you think I am.

Whether this was a plea for help or a confession of some darker truth, I cannot say with certainty, but I believe now that the woman I saw in the attic and the woman who sat in the parlor the next day were both Elellanar Harrove, and yet somehow they were not the same person.

The Reverend died in 1916.

His reputation in Salem somewhat diminished by what many perceived as an unhealthy obsession with the Hargrove case.

His journals remained hidden until 1920, by which time most of the principles in the case had either died or disappeared.

In his final years, Reverend Blackwood had repeatedly attempted to interest authorities in reopening an investigation into the Hargrove affair.

His efforts were largely dismissed as the ravings of a man in declining mental health.

However, among his personal effects was found a collection of carefully preserved newspaper clippings detailing missing person’s cases across New England between 1895 and 1915.

Each clipping had been annotated in Blackwood’s handwriting, noting similarities in physical appearance between the missing women and Elellanar Harrove.

Most strikingly, several of these cases involved reports of a well-dressed, cultured woman seen in the vicinity shortly before the disappearance.

Blackwood had circled these descriptions and written in the margin, MH, still practicing her art.

One such case from 1900 involved the disappearance of a librarian in Portsouth, New Hampshire.

According to witnesses, the woman had been engaged in conversation by a refined lady from Boston on the day she vanished.

The description of this visitor, tall with auburn hair and an aristocratic bearing, matches known descriptions of Margaret Hargrove.

Most disturbingly, the missing librarian was reported to bear a striking resemblance to Elellanar Harrove in terms of height, build, and coloring.

6 months after this disappearance, a new resident arrived in a small town in Vermont, claiming to be the same librarian and explaining her absence as an extended visit to relatives.

According to local accounts, however, acquaintances noted subtle changes in her demeanor and habits.

She remained in the town for approximately 3 years before departing suddenly, leaving behind most of her possessions.

Blackwood had connected this case with five others following a similar pattern across New England.

In each instance, a woman disappeared, only for someone claiming to be her to reappear weeks or months later, changed in subtle ways that friends and family could not quite articulate.

In each case, the reappearance was preceded by sightings of a woman matching Margaret Hargro’s description.

One final piece of evidence emerged in 1919 when renovations to a building in Portsouth, New Hampshire, uncovered a letter sealed in the wall cavity.

The letter dated October 1895 and signed M.

Hargrove was addressed to an unknown recipient.

It read in part, “The procedure was more difficult than anticipated, but ultimately successful.

The subject retained too much of her original identity at first.

necessitating additional measures.

The fire was regrettable but necessary to eliminate all evidence.

I am satisfied that no connection can be established between my former and current identities.

The techniques documented in our grandfather’s journals have proven effective, though the psychological component requires refinement.

I look forward to discussing modifications for future applications.

The letter continued, “I have identified a promising candidate in Portsmouth who shares the required physical characteristics.

Initial observations suggest a suitable psychological profile as well, intelligent but isolated with few close connections to complicate the transition.

I have established contact under the guise of research into local history and have been invited to her home next week.

” The groundwork has been laid carefully with attention to the refinements we discussed after the previous attempt.

I do not anticipate the same difficulties that arose with e.

The letter was turned over to authorities in Portsmouth, but was subsequently lost or destroyed before it could be properly investigated.

Only a clerk’s transcription remains, filed with miscellaneous historical documents in the city archive.

What actually transpired in the attic of the Harrove mansion may never be fully known.

The systematic removal of evidence combined with the passage of time and the death of all directly involved parties has left us with more questions than answers.

What seems clear, however, is that something occurred that was disturbing enough to warrant an organized effort to erase it from public memory.

Some historians specializing in New England history have suggested that the case may have connections to certain esoteric practices allegedly brought to Salem by European immigrants in the mid 19th century.

These practices involving concepts of identity transference and psychological manipulation were documented in several obscure texts confiscated during an unrelated investigation in Boston in 1900.

One such text, a leatherbound manuscript titled Transformations of the Self, contained detailed instructions for what it described as the assumption of another’s essence.

The author, identified only by the initials THG, wrote of experiments conducted in the 1850s involving the systematic breaking down of a subject’s sense of self through isolation, manipulation, and the careful introduction of elements from the identity to be assumed.

The parallels between these practices and what appears to have occurred in the Harrove attic are difficult to ignore, especially given the similarity of the initials to Thaddius Hargrove’s grandfather, Thomas Henry Granger, who changed the family name upon immigration to America in 1820.

Others propose more mundane explanations that Elellanar Harrove suffered from a mental illness misunderstood in that era.

That Margaret’s actions, while cruel, were motivated by misguided attempts at protection or treatment, and that local officials simply wish to avoid another scandal associated with the Salem name.

A psychological assessment conducted in 1962 by Dr.

Elizabeth Winters of the cases connected by Reverend Blackwood suggested a pattern consistent with what would now be recognized as a severe personality disorder characterized by identity obsession.

Dr.

Winners hypothesized that Margaret Hargrove may have suffered from a pathological need to assume her sister’s identity, possibly stemming from childhood trauma or developmental disorders not recognized in the 19th century.

What makes the Hargrove case particularly disturbing, Dr.

Winters wrote, is not just the apparent imprisonment and psychological torture of Ellaner, but the suggestion that this was not an isolated incident.

If the connections drawn by Reverend Blackwood are valid, we may be looking at one of the earliest documented cases of serial identity theft, not in the modern financial sense, but in a far more literal and disturbing manner.

Whatever the truth, the property where the Harrove Mansion once stood remains a public park to this day.

Local residents report that despite multiple attempts to plant trees in certain areas of the park, the soil there refuses to support growth.

The spot corresponding to where the attic would have been remains particularly barren, appearing as a dead patch in an otherwise green space.

In 1953, during installation of a water line through the park, workers uncovered a small metal box approximately 6 ft below ground.

The box, severely corroded, contained what appeared to be human hair tied with two different ribbons.

According to the work supervisor’s report, the hair was unusual in that it appeared to be from two different people, yet matched in color and texture almost perfectly.

The box and its contents were given to the local historical society, but disappeared from their collection sometime in the 1960s.

The supervisor, Walter Mitchell, provided additional details in an interview conducted in 1978 for an oral history project.

He described finding small personal effects alongside the hair.

A silver thimble, a woman’s wedding band, though neither Harrove sister had married, and most disturbingly, what appeared to be fingernail clippings arranged in two distinct patterns.

Mitchell claimed that these items had been carefully wrapped in silk cloth embroidered with the initials eh and mh intertwined.

The thing that struck me as odd, Mitchell recalled, was that the fingernail clippings were arranged to spell out words.

One set spelled help and the other Ellaner.

It gave me the creeps like someone had been trying to leave a message that couldn’t be found any other way.

This aspect of Mitchell’s account was omitted from the official report, possibly due to its fantastical nature or perhaps as part of the continuing effort to suppress details of the Hargrove case.

When researchers attempted to locate the items for examination in the 1970s, they were informed that no such artifacts had ever been part of the historical society’s collection.

Perhaps the most fitting postcript to the story comes from a woman who purchased a home on the street adjacent to the former Hard Grove property in 1970.

During renovations, she discovered a small diary hidden in a wall cavity dated 1894 and bearing the inscription property of Elellanar Hargrove.

The diary contained only a single entry written in an unsteady hand.

I hear her practicing my voice at night.

She stands before my mirror, wearing my clothes, speaking as I speak.

Yesterday I found a strand of my hair on her dresser carefully preserved.

I fear what she intends.

If you are reading this, know that I am Ellaner Harg Grove, the real Ellaner, and I am the entry ends abruptly mid-sentence.

The diary was reportedly turned over to a university archive for preservation, but like so many artifacts connected to the Harrove case, it cannot now be located.

The homeowner, Judith Mason, provided additional context in a local newspaper interview in 1972.

She described finding not just the diary, but also a small collection of personal items concealed in the same wall cavity.

a locket containing a miniature portrait of two identical-looking young women, a small key that matched the description of the one found among Jenkins’s possessions, and most intriguingly, a folded piece of paper containing what appeared to be the floor plan of the Harrove mansion’s third floor with a room marked that did not appear in the official architectural plans.

The strangest thing was the note written on the back of the floor plan, Mason stated.

It said, “The procedure requires a vessel emptied of self, then filled with another.

M believes I am being emptied, but I am merely becoming still.

When the time comes, she will find I am not as empty as she thinks.

” It was signed with the letter E, and dated June 3rd, 1894, just days before Reverend Blackwood’s visit.

This tantalizing suggestion that Elellanar might have been aware of and perhaps even preparing to counter her sister’s intentions adds yet another layer to the already complex narrative.

Was Elellanar truly a victim or was she engaged in her own form of resistance or even counter manipulation? The evidence is too fragmented to draw firm conclusions.

In 1988, an elderly woman was admitted to a nursing home in Western Massachusetts.

staff noted that she repeatedly told the same story about two sisters who had lived in Salem in the 1890s.

When questioned about how she knew this tale, the woman claimed to be the great niece of Martha Winters, the Harrove’s former cook.

According to this woman, whose name was withheld at her request, her great aunt had confided certain details on her deathbed that she had never before revealed.

Winters allegedly claimed that on the night she left the Hard Grover’s employment in March of 1894, she had witnessed Margaret entering Eleanor’s bedroom carrying a strange apparatus made of glass tubes and metal clamps.

Fearing what might be transpiring, Winters hid in an adjacent room and observed through a keyhole as Margaret administered some form of seditive to her sister.

Once Elellanar was unconscious, Margaret allegedly produced a small notebook and began making methodical measurements of her sister’s features.

The distance between her eyes, the width of her mouth, the angle of her jaw.

Martha told me she heard Margaret say, “Soon, sister, you will teach me everything I need to know.

Every gesture, every expression, every secret thought, and then I shall be you, only better.

” The elderly woman recounted.

That’s when Martha decided to leave.

She packed her things that night and never returned, not even for her final wages.

She said she couldn’t bear to be part of whatever was happening in that house.

While this account must be treated as third hand and therefore less reliable than contemporary documentation, it aligns disturbingly well with other evidence, suggesting that Margaret Hargarov had been engaged in a deliberate, methodical process of assuming her sister’s identity, not merely through imitation, but through some more fundamental and perhaps even physical transformation.

Today, more than a century after the events at the Harrove Mansion, Salem has largely forgotten the sisters and their disturbing story.

The park that stands on the property bears no marker of its history.

Town records make no mention of the house or its owners.

It is as if the Hardrove Sisters never existed at all.

Yet on certain nights, particularly during thunderstorms, residents near the park report hearing what sounds like a woman’s voice calling from somewhere that should be empty air three stories above the ground.

The voice reportedly calls the same thing each time.

A name that sounds like Ellaner, though distorted by distance and the howling wind.

In 2007, a graduate student researching disappeared person’s cases in New England made a startling discovery while examining cemetery records in a small town in Maine.

A grave marker dating from 1920 bore the name Margaret Elellanar Smith with the epitap, “She found herself at last.

” Beneath this conventional inscription, barely visible after decades of weathering, was a second line, eh, 1861 1920.

When the student attempted to find death records or obituaries for this Margaret Ellaner Smith, she discovered that no such person appeared in any official documentation for the town.

Furthermore, the cemetery’s interament record showed that the plot had been purchased in 1919 by a woman who paid in cash and left no contact information.

According to the cemetery caretaker’s notes, the woman had specified exact dimensions for the grave and had overseen the placement of the marker personally.

Most intriguing was the caretaker’s description of the purchaser.

Tall woman, refined manner, speaks like someone educated, hair going gray, but still shows auburn.

Says she’s preparing for her own eventual passing.

Something odd about her eyes.

Different colors, one brown, one blue.

This description matches no known account of either Harrove sister, both of whom were documented as having brown eyes.

However, medical notes from Dr.

Pierce regarding the remains found in the attic mentioned heterocchromia of recent origin, suggesting that one of Ellaner’s eyes had changed color, possibly due to trauma or medical experimentation.

Could this grave marker represent the final resting place of Elellanar Harrove, having somehow survived the fire and lived out her life under an assumed name? Or was it Margaret continuing her lifelong obsession with merging her identity with her sisters even in death? Without exumation, which local authorities have refused to authorize, we may never know.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of the Hargrove case is not what we know, but what remains hidden, erased from records, removed from archives, and deliberately forgotten.

It stands as a reminder that history is not merely what is recorded, but also what is deliberately omitted.

Not just what we remember, but what we choose to forget.

And sometimes what we choose to forget is precisely what we most need to

News

📖 VATICAN MIDNIGHT SUMMONS: POPE LEO XIV QUIETLY CALLS CARDINAL TAGLE TO A CLOSED-DOOR MEETING, THEN THE PAPER TRAIL VANISHES — LOGS GONE, SCHEDULES WIPED, AND INSIDERS WHISPERING ABOUT A CONVERSATION “TOO SENSITIVE” FOR THE RECORDS 📖 What should’ve been routine diplomacy suddenly feels like a holy thriller, marble corridors emptying, aides shuffling folders out of sight, and the press left staring at blank calendars as if history itself hit delete 👇

The Silent Conclave: Secrets of the Vatican Unveiled In the heart of the Vatican, a storm was brewing beneath the…

🙏 MIDNIGHT SHIELD: CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH URGES FAMILIES TO WHISPER THIS NEW YEAR PROTECTION PRAYER BEFORE THE CLOCK STRIKES, CALLING IT A SPIRITUAL “ARMOR” AGAINST HIDDEN EVIL, DARK FORCES, AND UNSEEN ATTACKS LURKING AROUND YOUR HOME 🙏 What sounds like a simple blessing suddenly feels like a holy alarm bell, candles flickering and doors creaking as believers clutch rosaries, convinced that one forgotten prayer could mean the difference between peace and chaos 👇

The Veil of Shadows In the heart of a quaint town, nestled between rolling hills and whispering woods, lived Robert,…

🧠 AI VS. ANCIENT MIRACLE: SCIENTISTS UNLEASH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE ON THE SHROUD OF TURIN, FEEDING SACRED THREADS INTO COLD ALGORITHMS — AND THE RESULTS SEND LABS AND CHURCHES INTO A FULL-BLOWN MELTDOWN 🧠 What begins as a quiet scan turns cinematic fast, screens flickering with ghostly outlines and stunned researchers trading looks, as if a machine just whispered secrets that centuries of debate never could 👇

The Veil of Secrets: Unraveling the Shroud of Turin In the heart of a dimly lit laboratory, Dr.Emily Carter stared…

📜 BIBLE BATTLE ERUPTS: CATHOLIC, PROTESTANT, AND ORTHODOX SCRIPTURES COLLIDE IN A CENTURIES-OLD SHOWDOWN, AND CARDINAL ROBERT SARAH LIFTS THE LID ON THE VERSES, BOOKS, AND “MISSING” TEXTS THAT FEW DARED QUESTION 📜 What sounds like theology class suddenly feels like a conspiracy thriller, ancient councils, erased pages, and whispered decisions echoing through candlelit halls, as if the world’s most sacred book hid a dramatic paper trail all along 👇

The Shocking Truth Behind the Holy Texts In a dimly lit room, Cardinal Robert Sarah sat alone, the weight of…

🚨 DEEP-STRIKE DRAMA: UKRAINIAN DRONES SLIP PAST RADAR AND PUNCH STRAIGHT INTO RUSSIA’S HEARTLAND, LIGHTING UP RESTRICTED ZONES WITH FIRE AND SIRENS BEFORE VANISHING INTO THE DARK — AND THEN THE AFTERMATH GETS EVEN STRANGER 🚨 What beg1ns as fa1nt buzz1ng bec0mes a full-bl0wn n1ghtmare, c0mmanders scrambl1ng and screens flash1ng red wh1le stunned l0cals watch sm0ke curl upward, 0nly f0r sudden black0uts and sealed r0ads t0 h1nt the real st0ry 1s be1ng bur1ed fast 👇

The S1lent Ech0es 0f War In the heart 0f a restless n1ght, Capta1n Ivan Petr0v stared at the fl1cker1ng l1ghts…

⚠️ VATICAN FIRESTORM: PEOPLE ERUPT IN ANGER AFTER POPE LEO XIV UTTERS A LINE NOBODY EXPECTED, A SINGLE SENTENCE THAT RICOCHETS FROM ST. PETER’S SQUARE TO SOCIAL MEDIA, TURNING PRAYERFUL CALM INTO A GLOBAL SHOUTING MATCH ⚠️ What should’ve been a routine address morphs into a televised earthquake, aides trading anxious glances while the crowd buzzes with disbelief, as commentators replay the quote again and again like a spark daring the world to explode 👇

The Shocking Revelation of Pope Leo XIV In a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming, Pope Leo XIV emerged…

End of content

No more pages to load