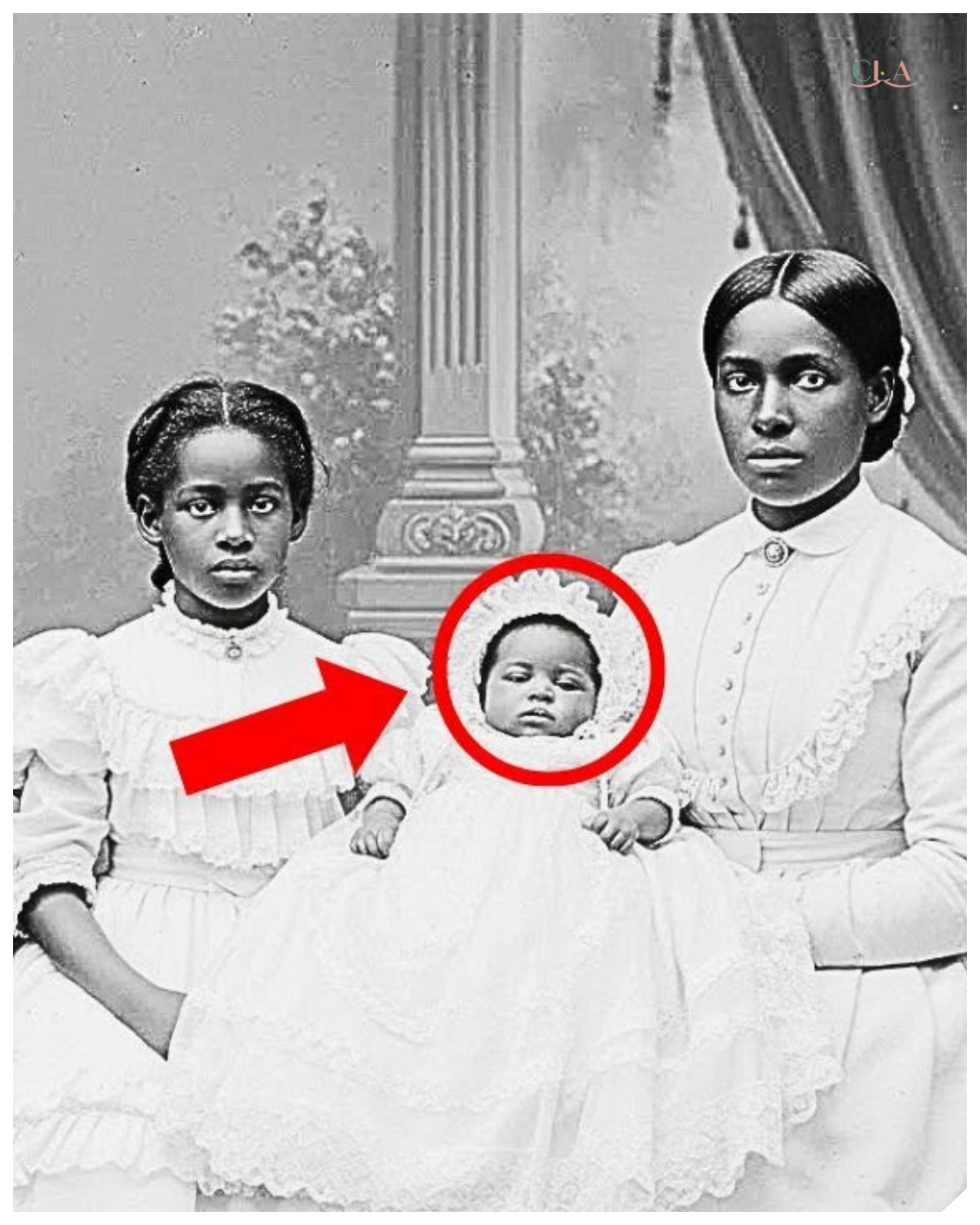

1888 household portrait found and historians are shocked when they zoom in on the child.

On April 13th, 2024, Dr.

Rebecca Martinez arrived at the Whitman estate sale in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, carrying nothing more than her camera bag and years of expertise in 19th century American photography.

The Victorian house stood on a quiet street in Shadyside, its rooms filled with the accumulated possessions of three generations.

The final owner, a 93-year-old woman named Dorothy Wittmann, had passed away three months earlier with no living relatives.

Rebecca specialized in documenting the visual history of black American families during the post Civil War era.

For 15 years, she had worked as lead archavist at the Carnegie Museum of American History, building one of the nation’s most comprehensive collections of African-American photographic records.

She knew the statistics intimately.

Fewer than 2% of photographs taken between 1865 and 1900 documented black families.

and of those, even fewer survived.

The estate sale had drawn the usual crowd of antique dealers, furniture collectors, and curious neighbors.

By the time Rebecca arrived at 9:30 that morning, most of the valuable items had already been claimed.

She moved methodically through the remaining boxes, her trained eye scanning for anything that might hold historical significance.

In a corner of the attic, beneath a stack of water damaged magazines from the 1950s, she found a metal tin box.

The container was rusted at the edges, its hinges stiff with age.

Inside, wrapped in yellowed tissue paper, lay approximately 40 photographs spanning different eras.

Rebecca’s pulse quickened as she carefully examined each image under the dim attic light.

Most were typical late Victorian family portraits, stiff poses, formal clothing, the characteristic sepia tones of albiman prints.

Then near the bottom of the collection, she found it, a photograph that would change everything she thought she understood about memorial photography in America.

The image showed a black family of five formally posed in what appeared to be a photographers’s studio.

The photograph measured approximately 8 by 10 in mounted on thick cardboard backing.

On the reverse side, written in faded iron gall ink were the words, “The Coleman family, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, June 1888.

” Rebecca paid the estate manager $15 for the entire tin of photographs and drove directly to her laboratory at the museum.

Something about that particular image had caught her attention, though she couldn’t yet articulate what it was, the family’s expression, perhaps the way they held themselves, or maybe it was simply the rarity of finding such a wellpreserved photograph from that specific time and place.

She had no idea that within hours this single photograph would reveal a truth that historians had never documented.

Dr.

Martinez arrived at the Carnegie Museum at 11:15 that morning.

The building was quiet on weekends with only security staff and a few dedicated researchers occupying the vast halls.

She made her way to the third floor conservation laboratory, a climate controlled room filled with specialized equipment for analyzing and preserving historical artifacts.

The photograph lay on her examination table, still in its original mounting.

Rebecca began with standard documentation procedures, photographing the image from multiple angles under controlled lighting.

She measured the dimensions precisely, 7.

9 by 9.

8 8 in.

The cardboard backing showed signs of age, but remained structurally sound.

The photograph itself displayed the characteristic glossiness of an albaman print, a process common in the 1880s that used egg whites to bind photographic chemicals to paper.

She turned her attention to the image itself.

The Coleman family stood arranged in a traditional studio composition.

The father, a man who appeared to be in his mid-30s, stood at the left wearing a dark suit with a high collar and a carefully knotted tie.

His expression was serious, dignified, his posture erect.

Beside him stood the mother, a woman of similar age, dressed in a high-neck dress with intricate buttons running down the front.

Her hair was pulled back severely, her hands folded at her waist.

Two children stood between their parents.

A boy of approximately 9 years old wore a miniature version of his father’s suit, his face solemn beyond his ears.

Beside him stood a girl of perhaps eight in a white dress with ruffled sleeves, her hair carefully braided.

Both children stared directly at the camera with the stillness required by long exposure times.

The mother held an infant in her arms wrapped in a white christening gown that cascaded down in elaborate folds.

The baby’s face was visible, peaceful, the tiny features clearly captured by the photographers’s lens.

Rebecca noted all of these details in her initial assessment log.

The photograph represented exactly the kind of historical document she sought to preserve.

A black family in 1888, formerly dressed, clearly having saved money to afford a professional studio sitting.

These images were acts of defiance and dignity in an era of systematic oppression.

Visual declarations that said, “We exist.

We matter.

Remember us.

” She placed the photograph under her highresolution digital scanner, a piece of equipment capable of capturing details invisible to the naked eye.

The machine hummed softly as it began its work, creating a digital file at 2400 dots per inch, a resolution that would allow her to examine every microscopic detail of the original image.

As the scan completed and appeared on her computer monitor, Rebecca began the process that would change everything.

She started to zoom in.

Rebecca’s examination followed her standard protocol.

She began with the background elements, noting the painted backdrop, typical of 1880s studio photography, a vague suggestion of columns and drapery meant to evoke Victorian elegance.

She examined the lighting, identifying the direction of the main light source and the subtle use of a reflector to soften shadows on the subject’s faces.

Then she moved to the subjects themselves, zooming in on each family member systematically.

The father’s face showed evidence of hard physical labor, calloused hands, weathered skin around the eyes, the bearing of a man who worked with his body.

The mother’s expression held a particular intensity that Rebecca had seen in other photographs from this era, a determination mixed with weariness that spoke to the specific burdens carried by black women in postreonstruction America.

The two older children displayed the typical rigidity of young subjects forced to remain motionless during long exposure times.

Rebecca could see the slight blur at the edges of the boy’s hand, suggesting he had moved slightly during the exposure, a common occurrence with children.

Finally, she directed her attention to the infant.

She increased the magnification to 400%, bringing the baby’s face into sharp focus on her screen.

At this magnification, every detail became visible.

the delicate fabric of the christristening gown, the careful way the mother’s hands supported the small body.

The baby’s face turned slightly toward the camera.

Rebecca’s hands froze on her mouse.

Something was wrong, deeply, fundamentally wrong.

The baby’s eyes were open, but they possessed a fixed quality that she recognized immediately from her years studying Victorian photography.

The skin tone, even accounting for the limitations of 19th century photographic chemistry, showed an unusual pour.

The tiny fingers visible beneath the gown’s lace cuffs rested in an unnatural position.

Most tellingly, there was an absolute absence of the slight motion blur that appeared on every other family member, even those who had held remarkably still.

This infant had not moved at all during the exposure, not even the involuntary movements that living bodies make.

The chest showed no expansion, the fingers no tension.

Rebecca leaned back in her chair, her professional detachment momentarily shattered.

She had just identified what historians call a memorial portrait or post-mortem photograph, a practice common in the Victorian era, where families would pose with deceased loved ones, particularly infants and children, as a way of preserving their memory in an age before modern death rituals.

But something about this particular image disturbed her in a way that professional examples had not.

The family’s expressions suddenly took on new meaning.

The mother’s intensity was not determination.

It was barely contained grief.

The father’s rigid posture was not dignity.

It was the physical manifestation of holding himself together.

The two older children’s faces showed not obedience but confusion and sorrow.

And the baby, dressed in white, held carefully in its mother’s arms, appeared for all the world to be peacefully sleeping.

Only the trained eye could see the truth.

This child was dead.

The family was participating in a final ritual of remembrance that was both heartbreaking and deeply human.

Rebecca sat in the silent laboratory, staring at the image on her screen and felt the weight of history pressing down on her shoulders.

Dr.

Martinez spent the remainder of that Saturday afternoon in her office, surrounded by reference books and historical journals.

She needed to contextualize what she had discovered to place the Coleman family photograph within the broader framework of Victorian morning practices and postmortem photography.

The practice had been widespread in America and Europe throughout the 19th century.

Before the advent of snapshot photography, many families never had their pictures taken at all, except when a death occurred, particularly the death of a child.

Infant mortality rates in the 1880s ranged from 15 to 30% depending on location and socioeconomic factors.

For black families in America, those numbers were often significantly higher due to limited access to medical care, inadequate housing, and the economic legacies of slavery.

Photographers specialized in memorial portraits, offering services that allowed grieving families to preserve a final image of their loved one.

The deceased, especially infants and young children, would be posed as if sleeping, sometimes held by family members, sometimes arranged in cribs or chairs.

Photographers used various techniques to create the illusion of peaceful rest, propping eyes open, positioning bodies carefully, using stands hidden beneath clothing to maintain posture.

Rebecca pulled several examples from the museum’s archives for comparison.

There was the Williams infant from 1882 photographed alone in an elaborate bassinet.

The Morrison twins from 1875 positioned together as if napping.

The elderly Mr.

Patterson from 1890 seated in his favorite chair with his family gathered around.

But as she compared these images to the Coleman family photograph, she began to notice significant differences.

Most memorial portraits made the death explicit in some way.

flowers arranged around the body, obvious positioning that suggested eternal rest, sometimes even captions or written notations indicating the nature of the photograph.

Families understood they were creating memorial images, and the photographs reflected that understanding.

The Coleman portrait was different.

At first glance, and even at second glance, the baby appeared completely alive.

The christristening gown suggested a celebration, not mourning.

The family’s formal poses could easily be interpreted as simply Victorian stiffness rather than grief.

Nothing in the composition explicitly indicated a memorial photograph.

This suggested several possibilities, each more intriguing than the last.

Perhaps the family had specifically requested that the photograph not obviously appear as a memorial portrait, wanting to remember their child as alive rather than dead.

Perhaps the photographer had possessed unusual skill in creating the illusion of life.

Or perhaps there was something else happening in this image, something that required deeper investigation.

Rebecca returned to her computer and began searching historical records.

The inscription on the back had provided crucial information.

The Coleman family, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, June 1888.

She accessed the digitized records of the Alageney County Archives, searching for birth records, death certificates, census data, anything that might tell her more about this family and their lost child.

The search took hours.

Pittsburgh in 1888 was a rapidly industrializing city.

Its population swelling with workers drawn to steel mills and factories.

Recordkeeping, especially for black residents, was inconsistent and often incomplete.

Many births went unregistered.

Deaths, particularly of infants, were sometimes documented only in church records or family bibles.

Finally, at 7:30 that evening, Rebecca found her first lead, a death certificate filed on June 18th, 1888 for an infant named Thomas Coleman, aged 3 months.

cause of death listed as summer complaint, a 19th century term for various gastrointestinal diseases that killed thousands of infants each year before modern sanitation and medicine.

Sunday morning found Dr.

Martinez back at her desk surrounded by printouts and notes.

The death certificate for Thomas Coleman had provided her first solid piece of evidence, but it raised as many questions as it answered.

She needed to learn more about this family, who they were, how they lived, what circumstances surrounded the death of their infant son.

She began with the 1880 United States Census conducted 8 years before the photograph was taken.

The census records for Pittsburgh’s black residents were frustratingly incomplete, but after several hours of searching variants of the name, she found them.

James Coleman, age 26, occupation listed as laborer.

Living at the same address was his wife Sarah Coleman, age 24, occupation listed as keeping house.

Two children, Michael Coleman, age 1, and Ruth Coleman, infant.

This matched the family in the photograph.

James would have been approximately 34 in 1888.

Sarah, 32, consistent with the ages suggested by their appearance in the image.

Michael and Ruth would have been 9 and 8, exactly as they appeared in the portrait.

Rebecca then turned to city directories, property records, and church registries.

She discovered that James Coleman worked at the Jones and Laughlin steel mill on the south side, one of Pittsburgh’s largest industrial facilities.

The family lived in the Hill District, a neighborhood that housed many of Pittsburgh’s black residents in the late 19th century.

The 1888 city directory listed James Coleman at an address on WY Avenue.

Rebecca cross referenced this with historical maps and found that the location would have been in a densely populated area near the base of the hill where workers housing crowded together in narrow streets, often without adequate sanitation or clean water.

Exactly the conditions that allowed diseases like summer complaint to spread rapidly through infant populations.

She found the Coleman family’s church, Bethl African Methodist Episcopal Church, established in 1808 and serving as a cornerstone of Pittsburgh’s black community.

Rebecca contacted the church’s current administrator and learned that many historical records had been preserved.

She scheduled a visit for Monday morning.

But there was something else nagging at Rebecca’s attention.

Something about the photograph itself that went beyond identifying it as a memorial portrait.

She returned to the highresolution scan, examining every detail with fresh eyes.

The family’s clothing, while formal, showed signs of careful mending.

The mother’s dress had been altered probably multiple times to extend its usefulness.

The father’s suit jacket showed slight differences in fabric texture that suggested patches or repairs.

Even the children’s clothing, while clean and pressed, bore the marks of handme-downs and careful preservation.

Yet, they had paid for a professional studio photograph.

In 1888, such a sitting would have cost a significant portion of a laborer’s weekly wages, perhaps two or three dollars, representing several days of work.

For a family living in worker’s housing, scraping together this money would have required sacrifice and planning.

Why? Why invest so heavily in photographing a dead infant? Memorial portraits were common, yes, but most families of limited means could not afford professional studio sessions.

They might have a traveling photographer take a simple image at home, or they might have no photograph at all, preserving memory only through oral tradition and morning rituals.

The Coleman family had chosen differently.

They had dressed in their finest clothes, brought their deceased infant son to a professional studio, and commissioned a formal portrait that positioned little Thomas as if he were alive, held lovingly in his mother’s arms, surrounded by his family.

This wasn’t just a memorial.

This was a statement.

Monday morning brought Rebecca to Bethl Ame Church, a modest brick building on Center Avenue that had stood for more than two centuries.

The current structure dated from 1925, but it occupied the site of earlier buildings that had served Pittsburgh’s black community since before the Civil War.

The church administrator, a retired school teacher named Dorothy Evans, met Rebecca in the basement archives.

“We don’t get many researchers down here,” Dorothy said, leading Rebecca through narrow aisles between filing cabinets and storage boxes.

Most of the historical societies focus on the wealthy neighborhoods, the industrialists and their families.

They forget that working people had history, too.

The church records from the 1880s filled three large ledgers, their pages brittle with age.

Dorothy handled them carefully, showing Rebecca how to support the binding while turning pages.

Birth records, baptisms, marriages, deaths, committee meetings, the daily life of a congregation documented in careful handwriting.

Rebecca found the Coleman family quickly.

James and Sarah had been married at the church in 1876.

Michael’s baptism was recorded in 1879, Ruth’s in 1880, and there in June 1888, she found what she was looking for.

Thomas James Coleman, born March 15th, 1888, died June 17th, 1888.

Baptized June 10th, 1888.

Interred Oakland Cemetery June 20th, 1888.

He was only 3 months old, Dorothy said softly, reading over Rebecca’s shoulder.

Summer complaint, you said that killed so many babies back then.

No refrigeration, no clean water in most neighborhoods, no understanding of hygiene.

The summers were terrible.

But it was another entry written in the margin in a different hand that caught Rebecca’s attention.

Photograph sitting arranged by congregation fund family memorial preserved.

The congregation paid for the photograph, Rebecca said, her voice tight with sudden emotion.

Dorothy nodded slowly.

The churches did that sometimes, especially for families who couldn’t afford it.

Death was expensive.

The burial plot, the coffin, sometimes a headstone if the family could manage it.

Many people died without any record except what was written in these books.

A photograph was a luxury most couldn’t dream of.

Rebecca photographed the page carefully with her camera, documenting every detail.

The congregation fund notation suggested something profound.

The community had collectively decided that the Coleman family’s grief deserved commemoration, that their lost child deserved to be remembered, that they would pull their resources to ensure this family had what wealthier families took for granted, a permanent image to hold on to when memory faded.

Is there anything else about the Coleman’s? Rebecca asked.

Any other records, letters, anything that might tell me more about them? Dorothy thought for a moment, then moved to a different section of the archives.

There might be something in the women’s auxiliary records.

Sarah Coleman.

That was the mother’s name.

Let me check.

She pulled down another ledger.

This one’s smaller.

Its pages filled with neat feminine handwriting.

The Women’s Missionary Society of Bethlme.

Church maintained detailed records of their activities, fundraising for missions, supporting widows and orphans, organizing food assistance for families in crisis.

Sarah Coleman’s name appeared multiple times.

She had been an active member participating in quilting circles, food preparation for church functions, and visitation of the sick.

The entry is painted a picture of a woman deeply embedded in her community.

Someone who gave her time and energy even while raising small children and managing a household on a laborer’s wages.

Then Dorothy found an entry from July 1888, one month after Thomas’s death.

Sister Sarah Coleman has requested leave from society duties while she recovers from her recent loss.

The society extends its deepest sympathy and assures Sister Coleman of our continued prayers and support.

Rebecca felt the historical distance collapse.

And these weren’t just names in a ledger.

Sarah Coleman had been a real woman who laughed and worried and loved her children and worked until her hands achd and woke in the night when her babies cried.

And when one of those babies died, she had needed time to grieve and her community had given it to her.

Rebecca’s next lead came from the photograph itself.

On the bottom right corner of the original cardboard mounting, partially obscured by age and wear, she had discovered an embossed mark.

Whitmore Photography Studio, Pittsburgh, Paw.

A search of city directories from the 1880s revealed that Whitmore’s studio had been located on Smithfield Street in downtown Pittsburgh in a building that no longer existed.

However, the Carnegie Library’s Pennsylvania room held an extensive collection of Pittsburgh business records, including some surviving documents from defunct photography studios.

By Tuesday afternoon, Rebecca had obtained access to a partial catalog from Whitmore Photography, donated to the library in 1952 by the photographers’s granddaughter.

The catalog was a revelation.

Benjamin Whitmore had operated his studio from 1875 to 1903, specializing in portraits of all classes and conditions.

His advertisement in an 1887 city directory emphasized respectful service to colored families, and memorial photography executed with sensitivity and care.

This was significant.

Many photographers of the era refused to serve black clients or charged them inflated prices or relegated them to inferior time slots and equipment.

Whitmore’s business records, though incomplete, showed regular appointments with black families from Pittsburgh’s Hill District and other working-class neighborhoods.

His pricing structure offered payment plans that allowed families to afford studio sessions they otherwise could never have managed.

Most intriguingly, Rebecca found a brief notation in Whitmore’s hand dated June 1888.

Coleman family memorial sitting infant prepared in natural sleep pose per family request.

Extra care taken with infant positioning and family composition.

Congregation of Bethl Church provided payment.

This family deserves dignity in their grief.

The phrase natural sleep pose confirmed what Rebecca had already determined.

The photographer had deliberately created an image where Thomas appeared to be peacefully sleeping rather than obviously deceased.

This wasn’t deception.

The family knew their child was dead, but rather an artistic choice that allowed them to remember him as he might have been.

held lovingly by his mother, surrounded by family, appearing for all the world like a drowsy infant at the end of a long day.

Whitmore’s note about dignity struck Rebecca deeply.

In an era when black Americans were systematically dehumanized, when their lives were considered less valuable, when their grief was dismissed or ignored, this white photographer had recognized the profound humanity of the Coleman family’s loss and had used his skill to honor it.

Rebecca found examples of Whitmore’s other work.

Standard studio portraits, wedding photographs, memorial images that were more obviously postmortem character.

The Coleman portrait represented his finest technical skill.

The lighting, the composition, the subtle positioning that maintained the illusion of life while still serving as a memorial.

She began to understand the photograph in a new light.

This wasn’t just a document of death.

It was a collaborative act of love and artistry, bringing together a grieving family, a supportive congregation, and a skilled photographer who understood that images could preserve not just appearance, but dignity, not just loss, but enduring connection.

Yet, questions remained.

What had happened to the Coleman family after this photograph was taken? Where had they gone? How had their photograph ended up in Dorothy Whitman’s attic, miles away from the Hill District where they had lived? And most importantly, had this family story, like so many others, simply vanished into the silence of history? Rebecca was determined to find out.

The breakthrough came on Wednesday afternoon through a source Rebecca hadn’t initially considered.

Death records from Oakland Cemetery, where little Thomas Coleman had been buried in June 1888.

The cemetery, established in the 1840s, served as the final resting place for thousands of Pittsburgh residents, including many from the city’s black community.

The cemetery’s historical society maintained detailed plot maps and burial records.

Rebecca drove out to the cemetery office located in a Victorian era building near the main gates and met with the archivist, an elderly man named Robert Chen, who had spent 40 years documenting the cemetery’s residence.

Thomas Coleman, Robert said, pulling up records on his computer.

Section 7, plot 42.

That’s in the older part of the cemetery up the hill.

The plot was purchased through Bethl Church’s burial fund.

They bought several plots to ensure their members had proper resting places.

Is there a headstone?” Rebecca asked.

The records show a marker was installed, though I can’t guarantee it’s still legible after all these years.

Would you like to visit the site? They walked together through the cemetery grounds, past ornate monuments and simple markers, through sections that told the story of Pittsburgh’s history in granite and marble.

Section seven occupied a gentle slope beneath oak trees, their branches creating patterns of light and shadow on the ground.

Plot 42 held a small weathered headstone, its inscription barely visible.

Thomas James Coleman, March 15th, June 17, 1888.

Beloved son, safe in the arms of Jesus.

Rebecca photographed the marker documenting another piece of the Coleman family story.

But Robert had more information to share.

I did some additional searching while you were driving out, he said, pulling a folder from his bag.

When you called yesterday asking about the Coleman’s, I got curious.

We have a database that tracks all burials and family plots.

The Coleman plot in section 7 has four burials.

Rebecca’s pulse quickened four Thomas in 1888 as you know then Sarah Coleman the mother in 1891 cause of death listed as tuberculosis she was only 35 years old James Coleman the father in 1902 aged 48 cause of death listed as industrial accident and Ruth Coleman in 1895 she was only 15 years old cause of death influenza the weight of it hit Rebecca like a physical blow three members of the family dead within seven years of the photograph being taken.

Only Michael, the older boy, was missing from the cemetery records.

“What happened to Michael?” Rebecca asked.

“That I don’t know,” Robert said.

“If he’s not buried here, he either moved away from Pittsburgh or is buried somewhere else.

” Given that the rest of the family is here, my guess would be he left the city.

Rebecca spent the rest of that afternoon in the cemetery photographing the Coleman family plot and searching for any other information that might provide leads.

The neighboring plots held other families from Bethl Church, creating a community in death as they had in life.

As the afternoon sun began to slant through the trees, Rebecca sat on a bench near the Coleman plot and considered what she had learned.

The photograph taken in June 1888, captured a family at a moment of devastating loss.

But that loss had been only the beginning.

Sarah, the mother, who had held her dead infant so tenderly in that photograph, had died just 3 years later, possibly already sick with the tuberculosis that would kill her.

Ruth, the 8-year-old girl in the white dress, had died at 15.

James, the father whose face showed such controlled grief, had died in a workplace accident at the steel mill.

Only Michael had survived, at least long enough to leave Pittsburgh.

Where had he gone? What had become of him? And how had the family photograph ended up in Dorothy Whitman’s attic? Rebecca pulled out her phone and began making notes, mapping out her next steps.

She would need to search census records from 1900 and 1910, looking for Michael Coleman.

She would need to investigate the Jones and Laughlin steel mill records, looking for details of James Coleman’s fatal accident.

She would need to trace property records in the Hill District, seeing if the family’s home could be identified, and she would need to find out who Dorothy Whitman was, and how a photograph of the Coleman family had come into her family’s possession.

The sun was setting as Rebecca left the cemetery, the long shadows stretching across the graves.

The Coleman family, dead for more than a century, had suddenly become vividly real to her.

Not just names and dates, but people who had loved and suffered and endured, whose story deserved to be told.

The link between the Coleman family and Dorothy Whitman proved to be the most challenging piece of the puzzle.

Rebecca spent Thursday morning at the Alageney County Property Records Office tracing ownership of the Shadyside House where the estate sale had been held.

The house had been built in 1920 and purchased by Dorothy’s parents, William and Elellanar Whitman, in 1935.

William had been a physician, Elellanar, a school teacher before her marriage.

There was no obvious connection between the Whitman’s, a white professional family in an affluent neighborhood, and the Coleman’s, a black working-class family from the Hill District.

The geographical and social distance between these families in late 19th century Pittsburgh would have been substantial, maintained by rigid racial segregation and economic inequality.

Rebecca was ready to abandon this line of inquiry when she discovered something unexpected.

Elellanar Whitman had taught at the Minersville School in the Hill District from 1915 to 1925 before leaving teaching to raise her own children.

The school had served predominantly black students, children of the workers who labored in Pittsburgh’s mills and factories.

This was the connection Rebecca needed.

She contacted the Pittsburgh Board of Education archives and requested any surviving records from the Minersville school.

2 days later, she received a package of digitized documents, including class rosters, teacher reports, and a box of materials that had been saved when the school closed in 1968.

Among these materials was a collection of student essays and assignments saved by Elellanar Whitman.

And there, in a folder marked family history projects, 1920, Rebecca found a handwritten composition by a student named David Coleman.

The essay, written in careful cursive on lined paper, began, “My father’s name is Michael Coleman.

He came to Pittsburgh from North Carolina when he was young.

His father died when he was 12 years old.

His mother and sister had already died of sickness.

He was alone, but he worked hard and made a life for himself.

He got married and had me and my two sisters.

My father says we must honor the family that came before us, even though they are gone.

He has a photograph of them that he keeps in a special box.

He says it reminds him where he came from and why he must be strong.

Rebecca’s hands trembled as she read the words, “Michael Coleman had survived.

He had stayed in Pittsburgh or returned to it and he had started his own family and he had kept the 1888 photograph, the last image of his family before tragedy destroyed them one by one.

There were more documents in the folder.

Ellen Whitman had written notes on David Coleman’s essay.

Excellent work.

This student shows deep respect for family history.

Spoke with him after class about the importance of preserving these memories.

And then in a separate note dated 1925, David Coleman’s father passed away suddenly last week.

Pneumonia.

The family is struggling.

David may need to leave school to work.

I offered to help however I can.

Rebecca found the death certificate.

Michael Coleman died February 1925, aged 46.

Cause of death, pneumonia.

He had survived his entire immediate family, built a new life, raised children, and still died relatively young.

Another casualty of the harsh conditions faced by working-class families in industrial Pittsburgh.

But the trail didn’t end there.

Rebecca found one more document.

A handwritten note from Eleanor Whitman to the school principal dated March 1925.

Principal Morrison, I wanted to inform you that David Coleman has had to leave school to help support his family.

His father’s death has left them in difficult circumstances.

I’ve offered to tutor David privately when possible, and I have taken possession of some family photographs that Michael Coleman’s widow wanted to ensure were preserved.

She fears they may be lost or sold if the family faces further hardship.

I assured her I would keep them safe.

Elellanar Whitman.

There it was.

Elellanar Whitman, a white school teacher in 1925, had taken possession of the Coleman family photograph to protect it at the request of a grieving widow who feared losing the last tangible connection to her husband’s tragic past.

And Elellanar had kept that promise, preserving the photograph for nearly a century until it ended up in her daughter Dorothy’s attic, where Rebecca had discovered it 99 years later.

On a warm morning in June 2024, exactly 136 years after the Coleman family photograph was taken, Dr.

Dr.

Rebecca Martinez stood before a gathering of 40 people in the Carnegie Museum’s main hall.

She had spent three months preparing this moment, and now the fruits of her research were ready to be shared.

The exhibition was titled The Coleman Family: Memory Loss and Resilience in Pittsburgh’s Black Community, 1888 1925.

The centerpiece was the photograph itself, professionally conserved and mounted, displayed at eye level with careful lighting that brought out every detail.

But the photograph was no longer alone.

Surrounding it were the other pieces of the Coleman family story.

painstakingly reconstructed census records showing James Coleman’s work at the steel mill church records documenting the family’s participation in Bethl amme church on the notation from Benjamin Whitmore’s studio log showing the congregation had funded the photograph burial records and photographs of the family plot in Oakland cemetery David Coleman’s school essay about his father Michael Ellanar Whitman’s notes showing how she had preserved the photograph the exhibition text explained what Rebecca had discovered written in clear language that honored the complexity of the story.

This photograph taken in June 1888 shows the Coleman family of Pittsburgh at a moment of profound grief.

The infant held by Sarah Coleman is her son Thomas, who had died the day before at 3 months of age.

The family could not afford a professional photograph, but their church congregation pulled resources to pay for this memorial portrait.

Photographer Benjamin Whitmore created an image where Thomas appears peacefully asleep, allowing the family to remember him with love rather than only with loss.

Within 7 years of this photograph, three more members of the family would be dead.

Ruth at 15 from influenza, Sarah at 35 from tuberculosis, and James at 48 from a workplace accident.

Only Michael, the older boy, survived to adulthood.

He built a new family and preserved this photograph as a link to those he had lost.

This single image represents countless untold stories of infant mortality in an era before modern medicine, of the dangers faced by industrial workers, of epidemics that devastated working-class communities, of racial segregation that limited opportunities and access to care.

It also represents resilience, a community that supported its members in crisis, a photographer who honored the humanity of all his clients, a family that insisted on being remembered with dignity, and a school teacher who kept a promise to preserve memory across generations.

The Coleman family story is Pittsburgh’s story and America’s story.

By recovering and sharing their narrative, we honor not only them, but all the families whose histories have been lost, forgotten, or ignored.

Al the audience included several descendants of the Coleman family, located through genealological research that had traced Michael Coleman’s children and grandchildren.

David Coleman’s granddaughter, a 72-year-old woman named Patricia Johnson, stood beside Rebecca as they looked at the photograph together.

I never knew any of this,” Patricia said softly.

“My grandfather David died when I was a baby.

My father didn’t talk much about the family history.

I knew we had roots in Pittsburgh, but I didn’t know about the photograph or about Thomas or any of it.

Your great great grandparents wanted to be remembered.

” Rebecca said they saved money they didn’t have, accepted help from their community, and sat for this photograph because they understood that memory matters.

That their baby son’s life, however brief, deserved to be commemorated, that their family, despite all the forces trying to erase them from history, was worth remembering.

Patricia nodded, tears visible in her eyes.

“Can I get a copy of the photograph?” “I’ll do better than that,” Rebecca said.

“The museum is creating highresolution prints for all the family members we found.

You’ll each receive one along with copies of all the research materials, the documents, the records, everything that tells your family’s story.

As the exhibition opened to the public, Rebecca watched visitors move through the space, reading the text panels, examining the documents, and standing before the photograph itself.

Many lingered there, looking at the faces of James and Sarah and Michael and Ruth and baby Thomas, seeing in them the universal human experiences of love and loss.

The Coleman family, dead for more than a century, were no longer forgotten.

Their photograph taken in a moment of devastating grief had become a bridge across time, connecting past and present, reminding everyone who saw it that every life matters, every loss deserves acknowledgement, and every family’s story is worth preserving.

The baby in the photograph was still dead.

Of course, that fact could not be changed.

Thomas James Coleman had lived only 3 months, dying in June 1888 from a disease that modern medicine could easily cure.

But because his family loved him, because their community supported them, because a photographer used his skill with compassion, and because a teacher kept a promise for nearly a century, Thomas was not forgotten.

He was remembered.

His family was remembered.

And through this exhibition, their story would continue to be told, ensuring that the Coleman family struggle and resilience would inspire future generations to honor the past, acknowledge the difficult truths of history, and work toward a future where all families and stories are valued equally.

Dr.

Rebecca Martinez returned to her office that evening, exhausted but satisfied.

On her desk lay the original photograph, ready to be returned to climate controlled storage.

She looked at it one last time before carefully placing it back in its archival box.

The Coleman family looked back at her across 136 years, their faces solemn and dignified, their grief held with such careful control, their love visible in every line and shadow.

They had wanted to be remembered and now finally they

News

🌲 IDAHO WOODS HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES DURING SOLO TRIP — TWO YEARS LATER FOUND BURIED UNDER TREE MARKED “X,” SHOCKING AUTHORITIES AND LOCALS ALIKE ⚡ What started as a quiet getaway turned into a terrifying mystery, as search parties scoured mountains and rivers with no trace, until hikers stumbled on a single tree bearing a carved X — and beneath it, a discovery so chilling it left investigators frozen in disbelief 👇

In August 2016, a pair of hikers, Amanda Ray, a biology teacher, and Jack Morris, a civil engineer, went hiking…

⛰️ NIGHTMARE IN THE SUPERSTITIONS: SISTERS VANISH WITHOUT A TRACE — THREE YEARS LATER THEIR BODIES ARE FOUND LOCKED IN BARRELS, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE COMMUNITY 😨 What began as a family hike into Arizona’s notorious mountains turned into a decade-long mystery, until a hiker stumbled upon barrels hidden in a remote canyon, revealing a scene so chilling it left authorities and locals gasping and whispering about the evil that had been hiding in plain sight 👇

In August of 2010, when the heat was so hot that the air above the sand shivered like coals, two…

⚰️ OREGON HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES WITHOUT A TRACE — 8 MONTHS LATER THEY’RE DISCOVERED IN A DOUBLE COFFIN, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE TOWN 🌲 What began as a quiet evening stroll turned into a months-long nightmare of missing posters and frantic searches, until a hiker stumbled upon a hidden grave and police realized the truth was far darker than anyone dared imagine, leaving locals whispering about secrets buried in the woods 👇

On September 12th, 2015, 31-year-old forest engineer Bert Holloway and his 29-year-old fiance, social worker Tessa Morgan, set out on…

🌲 NIGHTMARE IN THE APPALACHIANS: TWO FRIENDS VANISH DURING HIKE — ONE FOUND TRAPPED IN A CAGE, THE OTHER DISAPPEARS WITHOUT A TRACE, LEAVING INVESTIGATORS REELING 🕯️ What started as an ordinary trek through the misty mountains spiraled into terror when search teams stumbled upon one friend locked in a rusted cage, barely alive, while the other had vanished as if the earth had swallowed him, turning quiet trails into a real-life horror story nobody could forget 👇

On May 15th, two friends went on a hike in the picturesque Appalachian Mountains in 2018. They planned a short…

📚 CLASSROOM TO COLD CASE: COLORADO TEACHER VANISHES AFTER SCHOOL — ONE YEAR LATER SHE WALKS INTO A POLICE STATION ALONE WITH A STORY THAT LEFT OFFICERS STUNNED 😨 What started as an ordinary dismissal bell spiraled into candlelight vigils and fading posters, until the station doors creaked open and there she stood like a ghost from last year’s headlines, pale, trembling, and ready to tell a truth so unsettling it froze the entire room 👇

On September 15th, 2017, at 7:00 in the morning, 28-year-old teacher Elena Vance locked the door of her home in…

🌵 DESERT VANISHING ACT: AN ARIZONA GIRL DISAPPEARS INTO THE HEAT HAZE — SEVEN MONTHS LATER SHE SUDDENLY REAPPEARS AT THE MEXICAN BORDER WITH A STORY THAT LEFT AGENTS STUNNED 🚨 What began as an ordinary afternoon spiraled into flyers, helicopters, and sleepless nights, until border officers spotted a lone figure emerging from the dust like a mirage, thinner, quieter, and carrying answers so strange they turned a missing-person case into a full-blown mystery thriller 👇

On November 15th, 2023, 23-year-old Amanda Wilson disappeared in Echo Canyon. And for 7 months, her fate remained a dark…

End of content

No more pages to load