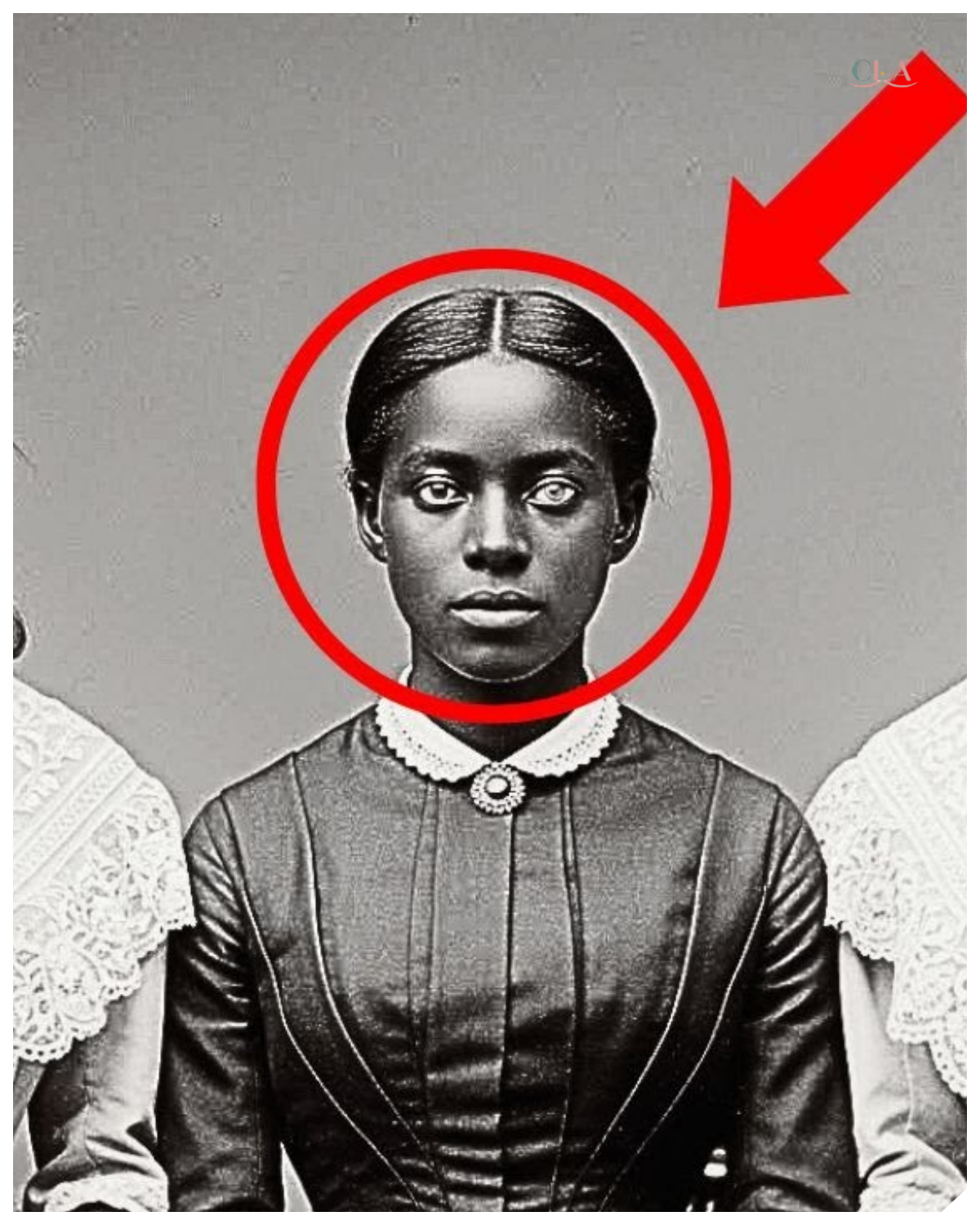

1877 studio photo found and restoers were stunned when they zoomed in on its eyes.

On September 14th, 2024, Amanda Foster stood in the conservation laboratory of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, examining a photograph that had arrived 3 days earlier as part of a donated collection.

The donation came from the estate of Margaret Harrison, a 90-year-old antiquarian who had spent her life collecting historical documents and photographs related to Philadelphia’s 19th century history.

Among the 200 items in the collection, this particular photograph had immediately caught Amanda’s attention.

The image showed three young women, approximately 16 to 18 years old, posed in a formal studio setting.

The photograph was dated 1877 written in faded ink on the reverse side along with a partial address, Chestnut Street Studio, Philadelphia forum.

The cardboard mounting showed significant age deterioration with water staining along the bottom edge and foxing throughout, but the photograph itself remained remarkably clear.

Amanda specialized in photographic restoration and conservation with particular expertise in 19th century American portraiture.

She had worked at the museum for 12 years, handling thousands of historical photographs.

But something about this image felt different.

The composition was striking.

Three young women arranged in a triangular formation, their faces showing the characteristic seriousness of Victorian era portraiture.

Yet their positioning suggested genuine friendship rather than formal obligation.

Two of the young women were white, dressed in elaborate gowns with high collars and intricate lace detailing.

The third, positioned slightly forward in the center of the composition, was a black woman wearing a simpler but well-made dress of dark fabric with modest ornamentation.

In an era of rigid racial segregation, the very existence of this photograph, three young women of different races posed together as apparent equals was historically significant.

Amanda began the standard documentation process, photographing the image from multiple angles under controlled lighting conditions.

She measured the dimensions 8.

2x 10.

1 in.

consistent with large format studio portraiture of the 1870s.

The photograph showed characteristics of the album in print process common for that period with a distinctive glossy surface and warm sepia tones.

She then placed the photograph under her highresolution digital scanner, a sophisticated piece of equipment capable of capturing microscopic details invisible to the naked eye.

The scanner would create a digital file at 3600 dots per inch, allowing her to examine every element of the original image with unprecedented clarity.

This level of detail often revealed information that transformed understanding of historical photographs, evidence of retouching hidden objects or physical characteristics that changed how the image should be interpreted.

As the scan completed and the image appeared on her monitor, Amanda began her systematic examination.

She started with the background elements, noting the painted studio backdrop that suggested classical architecture.

Then she examined each young woman’s clothing and positioning, looking for clues about their identities and relationships.

Finally, she zoomed in on their faces, beginning with the young woman on the left, then the one on the right, and finally the black woman in the center.

That’s when Amanda saw something that made her freeze, her hand hovering over her mouse.

Amanda increased the magnification to 800%, focusing on the face of the young black woman in the center of the photograph.

At this level of detail, every feature became sharply defined.

The texture of skin, the individual strands of hair carefully arranged, the fabric weave of her dress, and most strikingly, her eyes.

The young woman’s left eye appeared to be dark brown, consistent with what would be expected.

But her right eye showed a distinctly different coloration, significantly lighter, appearing almost hazel or light brown even through the sepia tones of the 19th century photographic process.

Amanda’s first thought was that this must be a defect in the photograph itself, perhaps damage to the original negative or uneven chemical processing.

She zoomed out and examined the photograph as a whole, looking for other signs of processing irregularities.

The image showed consistent tonal range throughout.

No other areas displayed unexpected color variations or chemical artifacts.

The eye difference appeared to be genuine, a characteristic of the subject herself, not the photograph.

Amanda pulled up her reference library of Victorian era photographic defects and anomalies, comparing the image to known examples of chemical staining, light leaks, and processing errors.

Nothing matched what she was seeing.

She then examined the other two young women’s eyes at the same magnification.

Both showed consistent uniform coloration in both eyes.

She sat back in her chair, considering the implications.

If this wasn’t a photographic defect, then the young woman in the image had heterocchromia, a condition where the two eyes have different colors.

The condition was rare in the general population, occurring in less than 1% of people and even rarer among individuals of African descent due to the genetic factors that influenced eye pigmentation.

But there was something else unusual about the way the eye appeared in the photograph.

Amanda noticed what seemed to be deliberate retouching around the lighter eye.

subtle manipulation of the photographic emulsion that suggested someone had tried to make the color difference less obvious.

In the 1870s, photographers sometimes retouched portraits to correct perceived imperfections or enhance certain features, but this retouching seemed intended specifically to minimize rather than eliminate the color difference.

Why would someone want to partially hide heterocchromia while still leaving it visible? The condition wasn’t considered shameful or problematic.

If anything, it was simply an unusual physical characteristic, notable, but not stigmatizing.

Amanda printed a highresolution copy of the image and began making notes.

She documented the eye color difference, the evidence of retouching, and the unusual composition of three young women of different races posed together as equals in 1877 Philadelphia.

Each element individually was interesting.

Together, they suggested a story that needed investigation.

She pulled the original photograph from its protective sleeve and examined the re reverse side more carefully.

The partial address, Chestnut Street Studio, provided a starting point.

She accessed the museum’s database of Philadelphia business directories from the 1870s, searching for photography studios on Chestnut Street.

Three studios appeared in the 1877 directory.

The largest and most prominent was Morrison Photography, which advertised portraits of distinguished families.

The second was Blackwell Studio, specializing in commercial and industrial photography.

The third, listed in smaller type, was simply called Howard, a studio, portraits of all citizens.

The phrase all citizens caught Amanda’s attention.

In the coded language of 19th century advertising, this likely indicated that the studio served clients regardless of race, a significant detail in an era when many businesses explicitly refused service to black customers.

Amanda spent Monday morning at the Philadelphia City Archives, a neocclassical building on Broad Street that housed millions of historical documents dating back to the city’s founding.

She had called ahead to request any available records related to Howard’s studio and photographers working on Chestnut Street in the 1870s.

The archivist, a meticulous woman named Dr.

Patricia Wells, had prepared several boxes of materials.

“Howard Studio is interesting,” Patricia said as she laid out the documents.

“The photographer was Jonathan Howard, a Quaker who operated from 1869 to 1889.

His business records show he deliberately cultivated clients from Philadelphia’s black community, which was unusual for the time.

The business ledgers revealed systematic documentation of Howard’s studio work.

Each entry included the client’s name, date of sitting, type of photograph ordered, and payment received.

The ledger for June 1877 showed an entry that immediately caught Amanda’s attention.

Portrait sitting, three young ladies.

Client Dr.

Thomas Blackwell, special commission, payment, $15.

$15 in 1877 was a substantial sum, equivalent to perhaps two weeks wages for a working-class family or several months rent.

This wasn’t a casual portrait sitting.

Someone had invested significantly in creating this photograph.

The name Dr.

Thomas Blackwell resonated vaguely in Amanda’s memory.

She accessed the archives biographical database and found multiple entries.

Dr.

Thomas Blackwell had been a prominent Philadelphia physician, practicing from the 1850s until his death in 1882.

He had trained at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School and established a practice that served both white and black patients, another unusual choice in an era of strict medical segregation.

More intriguingly, Dr.

Blackwell had been involved in various reform movements.

Records showed his membership in the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, his work with the Freriedman’s Bureau after the Civil War, and his advocacy for medical education reform.

He had also been investigated by the Philadelphia Medical Society in 1875 for inappropriate professional conduct.

Though the specific charges were not detailed in the available records, Amanda photographed the relevant ledger pages and continued searching.

She found Dr.

Blackwell’s death certificate listing his cause of death as heart failure at age 59.

His obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer was brief and formal, noting his medical practice and his survival by a wife and three daughters.

No mention of any sons or other children.

But then Patricia pulled out another document, a probate record from 1882.

Dr.

After Blackwell’s will had been contested, leading to a legal proceeding that generated substantial documentation, Amanda began reading through the file, and within minutes, she understood that she had found something significant.

The will included a bequest to Miss Katherine Morris, daughter of Elizabeth Morris, in recognition of natural affection and past services rendered.

The bequest amounted to $5,000, a fortune in 1882, along with certain personal property, including medical books, instruments, and all photographic portraits in my possession depicting the said Katherine Morris.

The will’s language was carefully constructed, but its implications were clear to anyone familiar with 19th century legal terminology.

Natural affection was often code for a biological relationship that could not be openly acknowledged.

Dr.

Blackwell was leaving money and property to a daughter he could not publicly claim.

The probate contest had been filed by Dr.

Blackwell’s legitimate daughters, arguing that the bequest to Katherine Morris was improper and that she had no legal claim to their father’s estate.

The case had proceeded through Philadelphia’s orphans court in 1883, generating depositions, witness testimony, and judicial rulings.

Amanda requested the complete probate file.

It arrived in three document boxes containing hundreds of pages of legal records.

She was going to need considerably more time to work through all of this material.

But already she could see the outline of a story emerging.

A story about identity, inheritance, race, and three young women whose friendship had been captured in a photograph that someone had paid a substantial sum to create.

Amanda spent the next 3 days immersed in the probate records, reading through depositions and court testimonies that painted an increasingly complex picture of Dr.

Thomas Blackwell’s life and the circumstances surrounding Katherine Morris.

The legal proceedings had been contentious with Dr.

Blackwell’s three legitimate daughters, Margaret, Elizabeth, and Sarah, contesting the bequest on multiple grounds.

The daughter’s attorney had argued that Katherine Morris was not Dr.

Blackwell’s biological child, and that she had unduly influenced him in his final years.

Their depositions described Catherine as a young black woman who had worked in their father’s medical office as a clerk and assistant beginning around 1873, when she would have been approximately 14 years old.

They acknowledged that their father had shown her favoritism, paying for her education and treating her with more consideration than was appropriate for her station.

But the most revealing testimony came from witnesses supporting Catherine’s claim.

A deposition from Dr.

Samuel Foster, a colleague of Dr.

Blackwell’s, stated plainly, “I have known Thomas Blackwell for 25 years.

He confided in me in 1875 that Katherine Morris was his daughter by Elizabeth Morris, a free woman of color with whom he had maintained a relationship before his marriage.

He felt great responsibility for Catherine’s welfare and wished to ensure her future security.

Another witness, a nurse named Mary Patterson, who had worked in Dr.

Blackwell’s practice, provided even more specific details.

Dr.

Blackwell told me that Catherine’s mother, Elizabeth Morris, had died in 1874 of consumption.

Before her death, she had made him promise to look after Catherine.

He honored that promise by bringing Catherine into his office and ensuring she received proper education.

He was particularly concerned about Catherine’s distinctive appearance.

She had one eye that was lighter than the other, which Dr.

Blackwell said was a family trait inherited from his side.

Amanda stopped reading and returned to the photograph on her desk.

The heterocchromia hadn’t been a random genetic occurrence.

It was a family trait, evidence of Catherine’s biological connection to Dr.

Blackwell.

In an era when children of mixed race relationships occupied a precarious legal and social position, this distinctive physical characteristic served as unmistakable proof of paternity.

The probate records continued with testimony about Katherine’s character and circumstances.

Multiple witnesses described her as intelligent, well educated, and respected within both the black and white communities she navigated.

Several testified that Dr.

Blackwell’s three legitimate daughters had known about Catherine for years and had even befriended her, which explained the photograph showing three young women of different races posed together.

A particularly striking deposition came from Jonathan Howard, the photographer who had taken the portrait.

He testified, “Dr.

Blackwell commissioned the photograph in June 1877.

He specified that he wanted a formal portrait of his three daughters together.

He used that word specifically, daughters.

He explained that Catherine’s distinctive eye coloring made some people uncomfortable, and he asked if I could minimize it slightly in the final print without eliminating it entirely.

He wanted the photograph to show Catherine as she was, but in a way that would not invite unwanted questions or comments.

I performed minimal retouching to soften the color contrast while preserving the characteristic.

So, the retouching Amanda had noticed wasn’t an attempt to hide the heterocchromia.

It was a careful balance between acknowledging Catherine’s distinctive appearance and protecting her from the social consequences of being too visibly different in an era of rigid racial categories.

The court’s final ruling issued in May 1883 was a compromise.

Judge William Hamilton acknowledged that the testimony strongly suggested Katherine Morris was indeed Dr.

for Blackwell’s daughter, but noted that 19th century law did not recognize children born outside of marriage as legal heirs with the same rights as legitimate children.

However, the judge upheld Dr.

Blackwell’s right to make whatever bequests he chose in his will.

Katherine received the $5,000 and the personal property, though the legitimate daughters retained the bulk of the estate, including their father’s house, medical practice building, and remaining financial assets.

The judge’s written opinion included a remarkable statement for 1883.

While the law cannot recognize Miss Morris’s claim to equal inheritance, simple justice and human decency require that Dr.

Blackwell’s wishes be honored.

He sought to provide for a young woman to whom he felt responsibility.

This court will not overturn those provisions.

With Katherine Morris’s name confirmed, Amanda began the process of tracing what had happened to her after the probate case concluded.

The 1880 United States census, taken three years after the photograph, listed Katherine Morris, aged 21, as living in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward, a predominantly black neighborhood.

Her occupation was listed as medical assistant, and she lived in a boarding house on Lombard Street.

The 1883 Philadelphia City Directory showed Katherine operating a small medical practice of her own, not as a licensed physician, which would have been nearly impossible for a woman, especially a black woman at that time, but as what was termed a medical practitioner or nurse practitioner.

Her advertisement in the directory read, “Katherine Morris, medical assistants for women and children, diseases of the eye, a specialty, ner 412, Lombard Street.

” The specialization in eye diseases made sense given her own distinctive condition.

Amanda wondered if Catherine had turned her unusual characteristic into a professional expertise, perhaps studying opthalmology under her father’s guidance before his death.

Amanda then searched newspaper archives looking for any mentions of Katherine Morris in Philadelphia papers between 1880 and 1900.

She found surprisingly numerous references.

Katherine had been active in several reform organizations, including the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and the Women’s Medical College Advocacy Group.

Several articles mentioned her work providing medical care to poor women in South Philadelphia.

One article from the Philadelphia Tribune, a black newspaper dated November 1889, provided substantial detail.

Miss Katherine Morris has established a dispensary for eye ailments at her practice on Lombard Street.

Miss Morris, who herself possesses a rare ocular condition, has made a particular study of diseases and injuries of the eye.

She treats patients regardless of their ability to pay and has gained recognition for her skill in preserving sight among factory workers and others whose employment damages their vision.

But what had happened to Catherine’s relationship with her halfsisters? Amanda returned to the photograph looking at the three young women posed together.

Margaret Elizabeth and Sarah Blackwell, Dr.

Blackwell’s legitimate daughters and Katherine Morris, his unagnowledged daughter, captured in a single image that represented both connection and separation.

Amanda found a clue in an unexpected place.

The records of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, a pioneering institution that provided art and design education to women when most universities excluded them.

The school’s enrollment records from 1878 1880 showed three students, Margaret Blackwell, Sarah Blackwell, and Katherine Morris, all studying together in the illustration and medical drawing courses.

They had remained friends, or at least continued their connection after the photograph was taken.

Despite the social barriers of race and the complicated family dynamics, the three young women had pursued their education together.

Amanda found Margaret Blackwell’s name in city directories through the 1890s, listed as a medical illustrator.

Sarah Blackwell appeared in records as a teacher at a girls academy.

Both women had never married, dedicating themselves to professional work.

Unusual, but not unheard of for educated women of their generation.

Then Amanda discovered something remarkable, a publication from 1895 titled Illustrated Guide to Ocular Diseases and Treatments by Katherine Morris and Margaret Blackwell.

The volume, published by a small Philadelphia medical press, combined Katherine’s Medical Expertise with Margaret’s illustration skills.

The book’s preface, written jointly by both authors, included a dedication to the memory of Dr.

Thomas Blackwell, who taught us that knowledge and compassion transcend all artificial boundaries.

Amanda contacted the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, an institution that maintained extensive archives of 19th century medical history.

The librarian, Dr.

Robert Kim, was intrigued by her inquiry about Katherine Morris and the illustrated medical guide she had co-authored with Margaret Blackwell.

The 1890s were a fascinating period for opthalmology, Robert explained when Amanda visited the college’s library on a rainy Thursday morning.

The field was just developing as a medical specialty.

Most physicians had minimal training in eye diseases.

Someone like Katherine Morris, working outside the formal medical establishment, could make real contributions if she had the right combination of practical experience and systematic study.

Robert had pulled several relevant materials, medical journals from the 1890s, membership records of medical societies, and copies of various publications related to eye diseases.

Among them was the illustrated guide Amanda had discovered, a slim volume of approximately 80 pages with detailed anatomical drawings and treatment protocols.

The book was remarkably sophisticated for its era.

Catherine’s text demonstrated thorough knowledge of ocular anatomy, common diseases like cataracts and glaucoma, traumatic injuries and infections.

Margaret’s illustrations showed precise anatomical detail clearly drawn from direct observation of actual patients and medical procedures.

Several illustrations specifically depicted heterocchromia and other pigmentation variations with detailed notes about how to distinguish harmless conditions from pathological changes.

This is highquality medical work, Robert said, carefully turning the pages.

The treatment protocols are consistent with the best medical knowledge of the period, and some of these observations about eye injuries among factory workers predate the industrial medicine movement by several years.

Katherine Morris was documenting occupational health hazards before most physicians recognized them as a distinct medical concern.

Robert showed Amanda a review of the book, published in the Pennsylvania Medical Journal in 1896.

The review was mixed, praising the quality of the illustrations and the practical utility of the treatment descriptions while noting that the authors lack formal medical credentials.

The reviewer concluded, “Despite the irregular nature of Miss Morris’s medical practice, this volume demonstrates considerable clinical experience and should be of value to rural physicians and others who encounter eye diseases without ready access to specialized consultation.

” Amanda asked about the heterocchromia Katherine displayed in the photograph.

Would that have affected her medical career or how she was perceived? Almost certainly, Robert replied.

Unusual physical characteristics were often interpreted through the lens of 19th century pseudoscientific theories about heredity, race, and fitness.

Heterocchromia might be seen as evidence of mixed blood or degeneration.

Uh, but it also might have given her credibility as someone who understood eye conditions from personal experience.

It’s complicated.

He pulled out another document, a letter written by Dr.

Thomas Blackwell to a colleague in 1876, one year before the photograph was taken.

The letter had been preserved in the college’s manuscript collection as part of a larger correspondence about medical education reform.

In the letter, Dr.

Blackwell wrote, “I have taken into my practice a young woman of considerable intelligence who possesses a distinctive physical characteristic affecting her eyes.

This characteristic, which is hereditary in nature, has led her to develop particular interest in ocular medicine.

I believe she has the capacity to make significant contributions to the field, but her sex and her race present obstacles that our profession has not yet overcome.

I’m attempting to provide her with the systematic education she deserves while recognizing that she will never receive the formal credentials her abilities warrant.

The letter confirmed what Amanda had already pieced together.

Dr.

Blackwell had been deliberately mentoring Catherine in medicine, recognizing both her potential and the systemic barriers she faced.

The heterocchromia, the very characteristic that marked her as visibly different and that provided evidence of her connection to doctor Blackwell had also sparked her medical interest and became the foundation of her eventual specialization.

Amanda’s next breakthrough came from an unexpected source.

While researching Margaret Blackwell’s later life, she discovered that Margaret had donated a collection of personal papers to the Pennsylvania Historical Society in 1924, 2 years before her death.

The collection included correspondents, journals, sketches, and family photographs.

Amanda requested access to the collection and spent an afternoon in the historical society’s reading room, carefully reviewing boxes of materials that chronicled Margaret Blackwell’s life from the 1870s through the 1920s.

Among the papers was a leatherbound journal that Margaret had kept sporadically between 1876 and 1885.

The journal entries from 1877 provided intimate details about the photograph that had started Amanda’s investigation.

An entry from June 15th, 1877 read, “Father has arranged for Howard to photograph the three of us together, Elizabeth, Sarah, and myself along with Catherine.

Mother protested initially, saying it was improper, but father insisted.

He said that Catherine is our sister, regardless of what society or the law recognizes, and he wants a portrait that shows our family as it truly is, not as convention demands it appear.

” Another entry dated June 20th, just after the photograph was taken, provided more context.

The sitting was awkward at first.

Catherine was nervous about her eye drawing attention in the photograph.

She’s always been self-conscious about how the different colors make people stare.

Howard was kind about it, explaining how he could minimize the contrast without hiding what makes Catherine herself.

I told her that her eyes are beautiful and that anyone who sees this photograph will understand that we are proud to call her our sister.

The journal revealed that the relationship between the four young women was more complex than Amanda had initially understood.

Yes, they were halfsisters, but they had developed genuine affection for one another despite the social barriers and family complications.

Margaret wrote about studying together, attending lectures at the School of Design, and discussing their futures.

But the journal also documented the tensions.

After Dr.

Blackwell’s death in 1882, Margaret wrote, “Mother is insisting that we contest father’s will.

She believes Catherine manipulated Father into leaving her money.

” that rightfully belongs to us.

Elizabeth and Sarah are willing to support mother’s position, but I cannot.

Father made his wishes clear, and Catherine deserves what he intended for her.

I fear this legal battle will destroy what remains of our sisterhood.

The probate case had indeed strained their relationships.

For several years, Margaret’s journal entries mentioned Catherine only briefly and with evident sadness.

But by 1887, a reconciliation had begun.

Margaret wrote, “I visited Catherine at her practice on Lombard Street today.

We had not spoken in nearly 2 years, and the distance between us has been painful.

She has built something remarkable, a medical dispensary serving the poor, particularly women and children.

She showed me her case notes and drawings of eye conditions she has treated.

Her knowledge surpasses what many trained physicians possess.

I suggested we might collaborate on an illustrated medical guide.

She seemed surprised, but pleased by the idea.

This was the beginning of their collaborative work on the medical guide Amanda had discovered.

The journal entries from the 1890s showed Margaret and Catherine working together regularly with Margaret creating illustrations based on Catherine’s clinical observations.

The final journal entry related to Catherine was dated 1902.

Catherine’s health is failing.

The years of overwork and the constant strain of navigating a profession that barely tolerates her presence have taken their toll.

She continues to see patients almost daily, refusing to slow down despite obvious fatigue.

I worry that she has perhaps five more years if she continues at this pace.

When I urge her to rest, she tells me that every patient she turns away might have nowhere else to go.

How do I argue with such dedication? Amanda searched death records for Catherine Morris, knowing from Margaret’s journal that Catherine’s health had declined in the early 1900s.

She found the death certificate dated April 3rd, 1907.

Catherine had died at age 48 from what was listed as pulmonary consumption, tuberculosis, at Philadelphia General Hospital.

The death certificate included several noteworthy details.

The informant who provided information for the certificate was Margaret Blackwell, listed as sister.

This was significant.

In 1907, Margaret had publicly claimed Catherine as her sister on an official document.

Despite the social implications and despite their relationship having no legal recognition, Catherine’s obituary appeared in both the Philadelphia Tribune and surprisingly in a brief notice in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

The Tribune’s obituary was substantial, describing Katherine’s medical work in detail.

Miss Katherine Morris, a pioneering medical practitioner who specialized in diseases of the eye, passed away after a long illness.

For more than 25 years, Miss Morris operated a medical dispensary serving Philadelphia’s poor.

She was known for her skill in treating eye injuries common among factory workers and for her refusal to turn away patients unable to pay.

She co-authored an important medical text on ocular diseases and trained numerous younger women in practical nursing skills.

She will be remembered as a dedicated healer who overcame significant obstacles to serve her community.

The inquirer’s notice was briefer but still remarkable for acknowledging Katherine at all.

Katherine Morris, medical practitioner, died April 3rd.

She was the daughter of the late Dr.

Thomas Blackwell and will be interred at Olive Cemetery.

A phrase daughter of Dr.

Thomas Blackwell appeared in print in a mainstream white newspaper 31 years after the photograph had captured the three sisters together.

Someone, almost certainly Margaret, had ensured that Catherine’s relationship to their father was finally acknowledged publicly.

Amanda visited Olive Cemetery, a small burial ground in North Philadelphia that had served the black community since the 1840s.

The cemetery records indicated that Katherine’s burial plot had been purchased by Margaret Blackwell.

The headstone still standing, though weathered by more than a century of exposure, read Katherine Morris Blackwell, 1859 1907.

Beloved daughter and sister, healer of the sick.

The use of Blackwell as part of Catherine’s name on the headstone was particularly significant.

She had lived her entire life as Katherine Morris, never legally entitled to use her father’s surname.

Only in death, through Margaret’s choice, did she receive the family name she had been denied in life.

Amanda photographed the headstone and searched for the graves of Margaret and Elizabeth and Sarah Blackwell.

She found them in Laurel Hill Cemetery, a prestigious cemetery where Philadelphia’s prominent families were buried.

The three sisters were interred together in the Blackwell family plot, their graves marked by a single large monument listing Dr.

Thomas Blackwell and his wife, followed by their three daughters.

The physical separation, even in death, Katherine buried in a black cemetery, her halfsisters in a white one, underscored the persistent racial divisions that had shaped their lives.

Yet Margaret had ensured Catherine bore the Blackwell name on her headstone and had publicly claimed her as a sister in death, if not in life.

Amanda’s final discovery came from the historical society’s photograph collection.

Among Margaret Blackwell’s donated papers was a second copy of the 1877 photograph.

This one with a note written on the back in Margaret’s handwriting dated 1924.

My sisters and myself taken by Howard Studio in June 1877.

From left, Sarah, myself, and Catherine.

We were young then and believed we might change the world.

Catherine came closest to achieving that dream.

I kept this photograph on my desk for 47 years.

MB Amanda spent two months preparing an exhibition based on her research.

The exhibition titled Three Sisters, Race, Medicine of Free Yan, and Friendship in Victorian Philadelphia would open at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in January 2025.

The centerpiece would be the 1877 photograph, but the story would be told through the extensive documentation Amanda had uncovered.

She worked with the museum’s exhibition design team to create a narrative that honored the complexity of the sister’s story.

The exhibition would include the original photograph, Jonathan Howard’s studio records, excerpts from the probate case, pages from Margaret’s journal, Catherine’s medical guide with Margaret’s illustrations, copies of the obituaries, and photographs of both cemeteries where the sisters were buried.

Most importantly, Amanda wanted to address the heterocchromia that had first caught her attention and that had played such a significant role in Catherine’s life.

She consulted with Dr.

Das Jennifer Park an opthalmologist and medical historian about how to present this aspect of the story accurately and sensitively.

Heterocchromia is simply a genetic variation in pigmentation.

Dr.

Park explained it’s not medically significant in most cases.

It doesn’t affect vision or indicate any underlying disease.

But in Catherine’s era, any physical difference could be interpreted through racist pseudocientific frameworks.

Her heterocchromia would have made her more visibly other in a society that was obsessed with racial categorization.

The exhibition text would explain Katherine Morris was born with heterocchromia iridium, a condition where the two eyes have different colors.

One eye was dark brown, the other significantly lighter.

This distinctive characteristic inherited from her father’s family served as visible evidence of her biological connection to Dr.

Thomas Blackwell.

In an era when children of interracial relationships existed in legal and social limbo, Katherine’s eyes told a truth that society preferred to ignore.

Rather than hiding this characteristic, she made it central to her medical work, specializing in diseases and conditions of the eye.

Amanda also wanted to include contemporary voices.

She contacted several descendants of Katherine Morris, located through genealological research.

Catherine had never married or had children, but her brother, son of Elizabeth Morris by another father, had descendants still living in Philadelphia.

One descendant, a retired nurse named Dorothy Johnson, agreed to participate in the exhibition.

My grandmother told me stories about Aunt Catherine, Dorothy said when Amanda interviewed her.

She said Catherine was brilliant and brave, that she treated people that nobody else would see, and that she never let anyone make her feel ashamed of who she was or where she came from.

My grandmother said Catherine’s different colored eyes were a gift, not a burden.

They helped her understand what it was like to be seen as different, and that made her a better healer.

Amanda also reached out to descendants of the Blackwell family.

She located a great great grandson of Sarah Blackwell, a historian named Michael Thompson who lived in Boston.

Michael was fascinated by the story Amanda had uncovered.

“The family always knew there was something complicated about our history,” Michael said during a video call.

“There were hints in old letters, vague references to a difficult situation involving my great great-grandfather.

” But the details were lost or deliberately suppressed.

To learn that we have this connection to Katherine Morris and to see evidence of how Margaret and the others honored that relationship despite enormous social pressure that’s meaningful.

Both Dorothy and Michael agreed to provide statements for the exhibition acknowledging the shared family connection across racial lines and across more than a century of silence.

The exhibition opened on January 17th, 2025, exactly 148 years after the photograph had been taken.

More than 200 people attended the opening reception, including descendants of both families, medical historians, museum staff, and members of the public who had been intrigued by advanced publicity about the discovery.

Amanda stood near the entrance, watching visitors encounter the photograph for the first time.

The image had been mounted at eye level with specialized lighting that brought out every detail.

Beside it, a digital interactive display allowed visitors to zoom in on Catherine’s eyes, seeing the heterocchromia that had started Amanda’s investigation nine months earlier.

The exhibition text began.

In September 2024, this photograph was discovered in a donated collection.

At first glance, it appeared to be a typical Victorian era studio portrait of three young women.

But careful examination revealed something extraordinary.

Evidence of a hidden family connection, a pioneering medical practice, and a friendship that defied the racial barriers of 1877 Philadelphia.

The young woman in the center is Katherine Morris, who possessed a rare condition called heterocchromia, eyes of two different colors.

This distinctive characteristic was inherited from her father, Dr.

Thomas Blackwell, a prominent Philadelphia physician.

The two young women flanking her are Margaret and Sarah Blackwell, Dr.

Blackwell’s legitimate daughters.

Though they shared a father, Catherine could not legally use the Blackwell name or claim her sisters publicly.

Yet, this photograph exists, commissioned by Dr.

Blackwell at substantial expense, it represents his determination to document his family as it truly was.

three daughters who loved each other and who would support each other through education, professional collaboration, and personal crisis.

The photograph is both a document of connection and a testament to the artificial barriers that divided families along racial lines.

Katherine Morris went on to become a pioneering medical practitioner specializing in diseases of the eye.

Turning her own distinctive characteristic into professional expertise, she treated patients that mainstream medicine ignored, documented occupational health hazards decades before they were widely recognized, and co-authored an important medical text with her sister Margaret.

She died in 1907, finally acknowledged as a Blackwell only on her gravestone.

This photograph survived because Margaret Blackwell kept it for 47 years, a private acknowledgement of a relationship that society refused to recognize.

It survived because it mattered to the people in it and to the people who loved them.

And now, more than a century later, it can tell its story.

Dorothy Johnson stood before the photograph for a long time, tears visible on her face.

She was so young, Dorothy said.

Just 18 in this picture and already dealing with so much, losing her mother, navigating between two worlds, knowing she had a father who loved her but couldn’t acknowledge her publicly.

And she took all that pain and turned it into something good.

She healed people.

Michael Thompson stood beside her, looking at the faces of his ancestors.

The thing that strikes me is how human this all is, he said.

Not the racism and the legal barriers, those are inhuman, monstrous.

But the love, the friendship, the determination to do right by each other despite the obstacles, that’s human.

That’s what survived.

That photograph could have been destroyed, lost, forgotten.

But Margaret kept it because it mattered to her.

And now we know why.

The exhibition included a final section titled Legacy and Recognition.

It documented Katherine’s medical contributions, showing how her observations about occupational eye injuries had influenced later industrial medicine research.

It displayed Margaret’s illustrations from their collaborative medical guide, noting how these images had been reprinted in medical textbooks for decades, usually without proper attribution.

And it addressed the question that Amanda knew visitors would ask.

Why had this story been forgotten for so long? The exhibition text explained Katherine Morris’s story was lost because stories like hers were systematically excluded from historical memory.

Medical histories focused on credentialed physicians trained at established institutions, almost exclusively white men.

Women’s contributions were minimized or attributed to male colleagues.

Black practitioners work was dismissed as inferior or ignored entirely.

And families divided by race often suppressed their connections rather than face social consequences.

Recovering Catherine’s story required piecing together fragments from multiple archives, court records, medical journals, private correspondents, cemetery records, and above all, this photograph.

Each piece alone told only part of the truth.

Together, they reveal a life of courage, skill, and dedication that shaped Philadelphia’s medical community and improved countless lives.

A legacy that deserves recognition.

As the evening concluded, Amanda stood one final time before the photograph, looking at the three young women who had posed together in 1877.

They looked back at her across 148 years, their faces serious, but united, their bond visible despite every force that had tried to separate them.

Catherine’s distinctive eyes, one dark, one light, no longer seemed like a medical curiosity or a historical detail.

They were evidence of identity, connection, and a truth that could not be hidden no matter how much society tried to deny it.

The heterocchromia that had marked her as different had also marked her as a Blackwell, linking her permanently to sisters who had loved her despite the cost.

The photograph had survived.

The story had survived.

And now finally, Katherine Morris Blackwell, healer, sister and pioneer, would be remembered.

News

In 1923, the ghastly Bishop Mansion in Salem became the setting of the most brutal Hall..

.

| Fiction

Before we begin, I invite you to leave in the comments where you’re watching from and the exact time at…

(1912, North Carolina) The Ghastly Ledger of the Whitford Family — Wealth That Devoured Bloodlines

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of North Carolina. Before we…

The Creepy Family in a Brooklyn Apartment — Paranormal Activity and Unseen Forces — A Ghastly Tale

Welcome to this journey of one of the most disturbing cases in recorded history, Brooklyn, New York. Before we begin,…

Hidden in the attic, the Harris family found ghastly proof of a disturbing case from th..

.

| Fiction

Welcome to this journey through one of the most disturbing cases recorded in the history of Bowfort, South Carolina. Before…

In Tennessee, a family found ghastly VHS tapes… showing disturbing reunions recorded ba..

.

| Fiction

Welcome to this journey of one of the most disturbing cases in recorded history Tennessee. Before we begin, I invite…

The TERRIFYING Haunting of Karen Byers — A Ghastly Tale

Welcome to this journey of one of the most disturbing cases in recorded history, Appalachian, Virginia. Before we begin, I…

End of content

No more pages to load