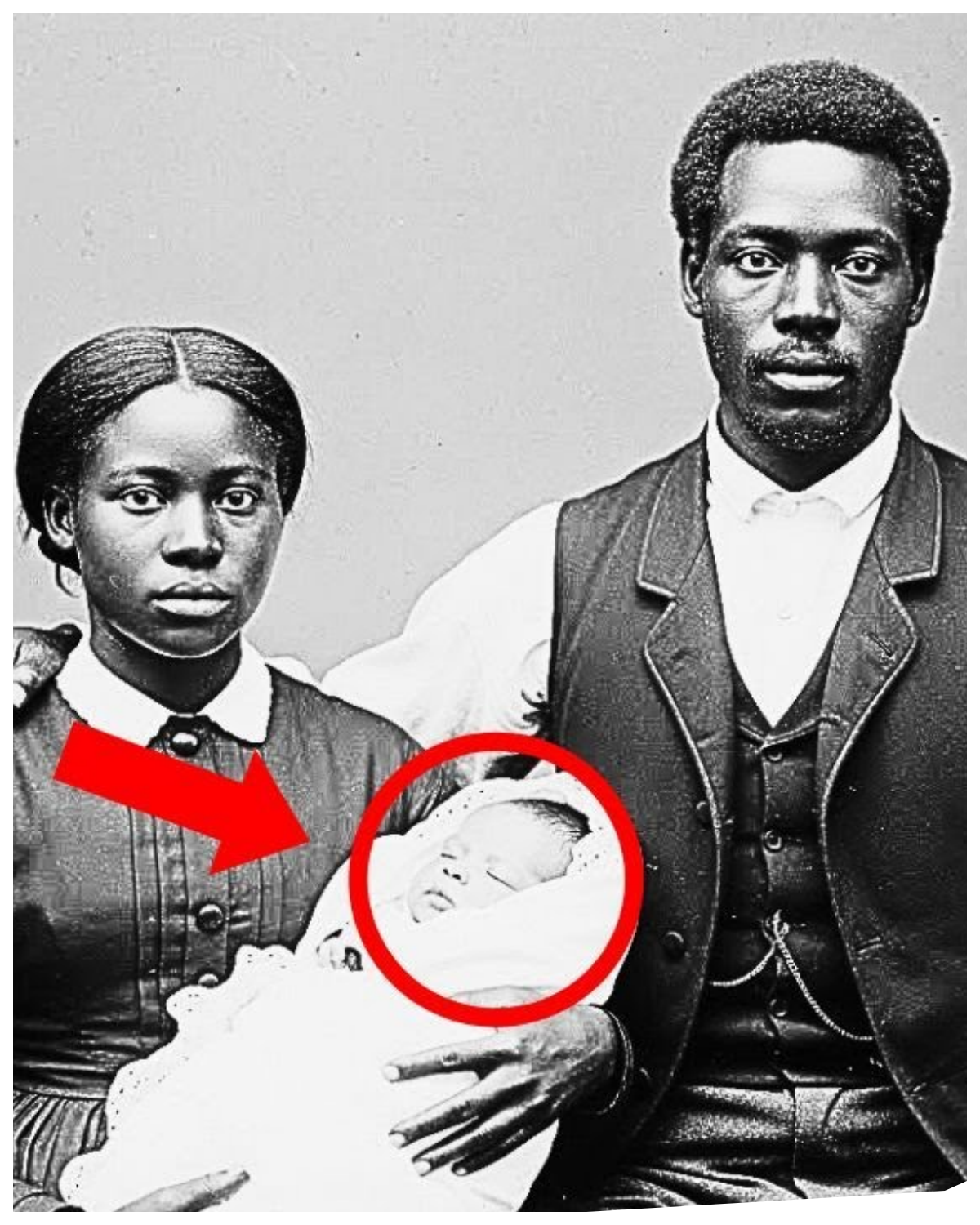

1866 Family Photo Restored — And Experts Freeze When They Zoom In on the Baby.

The photograph arrived at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington DC in March 2020, part of a large collection donated by descendants of Freriedman’s Bureau workers.

Senior conservator Michael Chen carefully removed it from its protective sleeve, noting the severe water damage along the edges and the fading that obscured much of the images detail.

The photograph was labeled simply Family Charleston, South Carolina, 1866 and faded pencil on the reverse.

At first glance, even through the damage and deterioration, Michael could make out three figures.

A black woman seated in the center, a black man standing beside her with his hand on her shoulder and what appeared to be an infant wrapped in white cloth and lace, cradled protectively in the woman’s arms.

Michael had restored hundreds of Civil War era photographs during his 15-year career.

But something about this image drew his attention.

The year 1866 was significant.

Just one year after the end of the Civil War, during the earliest days of reconstruction, when four million formerly enslaved people were navigating their first year of legal freedom in a South that remained dangerous and hostile, he placed the photograph under the digital microscope and began the painstaking process of highresolution scanning.

The museum had recently acquired cuttingedge restoration technology that could recover details invisible to the naked eye, penetrating layers of damage, aging, and chemical deterioration to reveal the original image beneath.

As the first highresolution scan appeared on his monitor, Michael leaned closer.

The couple’s faces were becoming clearer.

The woman looked to be in her mid-20s with dignified features and eyes that seemed to carry both strength and sorrow.

The man appeared slightly older, perhaps 30, his expression serious and protective.

Both wore simple but clean clothing, the kind that newly freed people might have saved for months to afford, but it was the bundle in the woman’s arms that made Michael pause.

As the restoration software continued processing, enhancing contrast and recovering faded details, something unexpected began to emerge.

The white cloth surrounding the infant wasn’t just wrapping.

It seemed deliberately arranged to cover most of the baby’s features.

With only a small portion of the face visible, Michael adjusted the enhancement settings, focusing specifically on that area of the photograph.

He increased the resolution, filtered out some of the water damage, and compensated for the chemical fading.

Then he saw it, or rather, he saw what didn’t make sense.

The visible portion of the infant’s skin tone appeared distinctly lighter than the parents holding the child.

Significantly lighter.

Michael sat back in his chair, his mind racing through possible explanations.

Photographic anomalies, chemical reactions in the aging process, uneven fading.

But he’d seen thousands of deteriorated photographs, and this didn’t match any known pattern of degradation.

He saved his work and called his colleague, Dr.

Sarah Mitchell, the museum’s chief historian specializing in reconstruction era African-American families.

Sarah,” he said when she answered, “I need you to look at something, and I need you to tell me I’m not seeing what I think I’m seeing.

” Dr.

Sarah Mitchell arrived at the conservation lab within the hour, her reading glasses perched on her head and a leather notebook tucked under her arm.

At 58, she had spent three decades studying the intimate lives of African-American families during and immediately after slavery, specializing in the complicated realities that official records often failed to capture.

Michael had the enhanced image displayed on the large monitor when she entered.

He didn’t say anything, simply gestured toward the screen and watched her face as she approached.

Sarah studied the photograph for a long moment, her expression shifting from casual interest to focused concentration.

She moved closer to the screen, examining the couple first, then letting her eyes travel down to the infant in the woman’s arms.

“Zoom in on the baby,” she said quietly.

Michael manipulated the image, enlarging the portion showing the infant’s partially visible face.

The contrast became even more apparent at higher resolution.

The skin tone was unmistakably lighter, the features suggesting European ancestry rather than African.

Sarah was silent for nearly a minute, her historian’s mind cataloging possibilities and implications.

Finally, she pulled up a chair and sat down, never taking her eyes from the image.

1866, she said, her voice measured.

Charleston, South Carolina, one year after the war ended.

She paused, choosing her words carefully.

Michael, do you know what Charleston was like in 1866? I know it was the heart of the Confederacy, one of the last cities to fall.

It was more than that.

It was where some of the wealthiest plantation owners in the South lived.

And when the war ended, those plantations didn’t just disappear.

The land was still there.

The former owners were still there.

And 4 million people who’d been enslaved were suddenly free, but with nowhere to go, no resources, no protection.

She pulled out her notebook and began writing.

During slavery, it’s estimated that hundreds of thousands of children were born from situations where enslaved women had no choice, no voice, no protection from their owners.

After emancipation, those children didn’t vanish.

Those families didn’t cease to exist.

They had to navigate an impossible situation.

How do you raise a child born from violence in a society that won’t acknowledge that violence even happened? Michael felt a heaviness settle in his chest.

You’re saying this baby? I’m saying this photograph might document something that most records from this period deliberately ignored or erased.

A black family, newly free, raising a child whose appearance revealed a brutal truth that everyone knew but no one wanted to discuss.

Sarah stood and moved closer to the image again, studying the woman’s face, her posture, the way her arms held the child.

Look at how she’s holding that baby.

That’s not ambivalence or shame.

That’s protection.

That’s love.

And look at him.

She pointed to the man, his hand on her shoulder.

That’s solidarity, support.

She turned to Michael.

We need to find out who these people were.

We need to know their story, not to sensationalize it, but to understand it.

Because this photograph represents thousands of families who faced this exact situation and whose stories were never told.

Michael nodded slowly.

Where do we start? Charleston, 1866.

We start with Freriedman’s Bureau records, church registries, birth records, if any exist.

We look for families registered in that year with children whose parentage might have been complicated.

And we handle this carefully, Michael.

This isn’t just historical curiosity.

This is someone’s family, someone’s ancestor.

There are likely descendants alive today who may or may not know this part of their history.

She pulled out her phone.

I’m calling Dr.

Robert Hayes at the College of Charleston.

He’s done extensive research on reconstruction era families in the Low Country.

If anyone has leads on where to find these records, it’s him.

As Sarah made the call, Michael looked again at the photograph, seeing it now not as a conservation project, but as a window into one of the most painful and complex aspects of American history, the aftermath of slavery, when freedom came with questions that had no easy answers, and families had to define themselves in a world that wanted to pretend their circumstances didn’t exist.

Dr.

Robert Hayes drove up from Charleston three days later, bringing with him two large boxes of photocopied documents from the Freriedman’s Bureau Archives, local church records, and personal papers he’d collected over 20 years of research.

A tall man in his 60s with silver hair and gentle eyes, he spread the materials across the museum’s research table with practice deficiency.

1866, Charleston, he began pulling out a ledger.

The Freriedman’s Bureau was overwhelmed.

They were trying to register thousands of formerly enslaved people, document marriages that had never been legally recognized, record births, established schools.

The records are incomplete, sometimes contradictory, but they’re all we have.

He opened the ledger to a marked page.

I searched for families registered in Charleston in 1866 with unusual circumstances noted.

The bureau workers were often northern whites who didn’t understand or want to acknowledge the complexities they were seeing.

But sometimes they left clues, hesitations in the records, marginal notes, unexplained details.

Sarah leaned forward as Robert pointed to an entry dated July 1866.

Thomas and Catherine, married by Bureau Authority, June 1866.

One child, infant, age not recorded.

Look at this notation in the margin, Robert continued, indicating faint pencil marks.

It says special circumstances, and then it’s crossed out.

That phrase appears in only a handful of records, usually when the registar encountered something they didn’t know how to document officially.

Michael photographed the page.

Is there an address? Any indication of where they lived? Robert pulled out a map of Charleston from 1866, handdrawn and annotated.

Based on cross-referencing multiple records, I believe they lived in an area called Hampstead, north of the city center.

It was one of several settlements where formerly enslaved people were trying to establish independent communities.

The land was poor.

Resources were scarce, but it was theirs.

He unfolded another document, a letter written by a Freriedman’s bureau teacher named Miss Elizabeth Warren to her family in Massachusetts, dated August 1866.

Sarah began reading aloud, “The situations I encounter here challenge every notion of propriety I was raised with.

Today, I met a young couple, Thomas and Catherine, who have taken on the care of an infant whose circumstances of birth are a testament to the cruelties these people endured.

The child’s appearance makes those circumstances apparent to anyone who looks.

Yet Thomas speaks of the baby with such tenderness, calling him our son without hesitation.

Catherine holds the child as fiercely as any mother I have seen.

They asked me to teach them to read so they might record their family’s story for the child when he grows older.

I was moved to tears by their dignity in the face of circumstances no family should have to navigate.

The room fell silent.

Sarah carefully set down the letter, her hands trembling slightly.

This has to be them.

The timing matches, the location matches, and the description matches what we see in the photograph.

Robert nodded.

There’s more.

I found a notation in a local church registry, St.

Steven’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, established in 1866.

It lists a baptism in September of that year.

Child of Thomas and Catherine, name recorded as Samuel.

There’s a note that the reverend performing the baptism was Reverend Elijah Martin, himself, a formerly enslaved person who’d become a minister.

Samuel, Michael repeated softly, looking at the infant in the photograph.

He had a name.

With Thomas, Catherine, and Samuel identified, the research team began searching for more information about their individual histories.

Dr.

Hayes returned to Charleston and spent two weeks in various archives, piecing together fragments from plantation records, sale documents, and testimonies recorded by Freriedman’s Bureau workers.

What emerged was Katherine’s story, or as much of it as could be recovered from records designed to reduce human beings to property.

She had been born around 1841 on Whitfield Plantation, 20 mi inland from Charleston.

The plantation records listed her only as Catherine, housemmaid, with no surname, no parents mentioned, no personal history acknowledged.

But Hayes found a notation in the plantation owner’s personal correspondence from 1858 that mentioned the housemaid Catherine who serves in the main residence.

Working in the main house rather than in the fields meant Catherine would have been in constant proximity to the plantation owner and his family.

For enslaved women, this proximity was often more dangerous than fieldwork, offering no protection and no escape.

Hayes discovered that Whitfield Plantation’s owner, Jonathan Whitfield, had died in 1864 during the final year of the war.

His property, including the enslaved people, had been divided among creditors and distant relatives.

The records didn’t show what happened to Catherine immediately after, but given that she appeared in Charleston Freriedman’s Bureau records in June 1866, she had likely walked away from the plantation as soon as news of emancipation reached the area.

Sarah found a brief testimony Catherine had given to a Freriedman’s Bureau worker in July 1866, recorded in bureaucratic shortorthhand.

Came to Charleston seeking work as infant born March 1866.

Wishes to marry Thomas Freiedman from Colton County.

Requests legal recognition of marriage.

The dates told a painful story.

If Samuel had been born in March 1866, he would have been conceived in June 1865, just weeks after the war ended.

But while Catherine was likely still trapped on or near Whitfield Plantation with nowhere to go and no one to protect her, she was free legally, Sarah explained to the research team.

But freedom without resources, without protection, without any system of justice that recognized crimes against black women, that wasn’t really freedom.

She was still vulnerable to the men who’d once claimed ownership over her body.

Thomas’ story was easier to trace.

Freriedman’s bureau records showed he had been enslaved on a smaller plantation in Colton County.

After emancipation, he’d worked as a laborer on the docks in Charleston, saving money and searching for a way to build a life.

How he and Catherine met wasn’t recorded, but by June 1866, they had decided to marry and raise Samuel together.

Hayes found one more document, a property record from November 1866, showing that Thomas had purchased a small plot of land in Hamstead for $12, an enormous sum for a formerly enslaved person.

The notation described it as 1/4 acre with small dwelling.

He bought land, Michael said, awe in his voice.

6 months after emancipation, while raising a child that wasn’t biologically his, he saved enough to buy property.

That’s extraordinary, Sarah nodded.

And she chose him.

She chose to build a family with a man who saw her worth, who saw Samuel’s worth.

That photograph wasn’t accidental.

They were documenting themselves as a family, claiming that identity publicly permanently.

As the team continued researching, they sought to understand what life would have been like for Samuel, a light-skinned child being raised by a black family in the immediate aftermath of slavery.

Dr.

Mitchell brought in Professor Angela Roberts, a sociologist who specialized in mixed race identity in 19th century America.

Children like Samuel existed in a painful liinal space, Professor Roberts explained during a research meeting.

Too white to be fully accepted in black communities.

Too black because of who raised him and where he lived to be accepted in white society.

And his very existence was evidence of violence that everyone knew about, but no one wanted to acknowledge.

She pulled up historical documents on her laptop.

But we have testimonies from this period describing children who grew up in similar circumstances.

Some faced hostility from within their own communities.

people who looked at them and saw the oppressor.

Others were embraced, especially when it was clear their parents loved them unconditionally.

Michael asked the question they’d all been considering.

What happened to Samuel? Did he survive childhood? Did he stay with Thomas and Catherine? Dr.

Hayes had been searching for exactly that information.

He’d found scattered references in Charleston records.

A Samuel listed in the 1870 census, living with Thomas and Catherine, age listed as four, race listed as mulatto, the term used then for people of mixed ancestry.

A notation in school records from 1873 showed a Samuel enrolled in a Freriedman’s Bureau school sponsored by Thomas and Catherine.

But after 1875, the trail went cold.

Samuel’s name disappeared from Charleston Records entirely.

That’s not unusual, Hayes explained.

Many people left the South during this period.

Violence against black communities increased as reconstruction collapsed.

Families scattered seeking safety or opportunity elsewhere.

Samuel might have moved north or west.

He might have changed his name if he was light-skinned enough.

He might have passed as white.

Sarah finished quietly.

It happened more often than we know.

Sometimes families made the painful decision to send light-skinned children away, give them new identities, new lives where they wouldn’t face the same violence and restrictions.

Professor Roberts nodded.

It’s one of the untold tragedies of this period.

Families torn apart not by slavery this time, but by the impossible choices freedom forced on them.

Do you raise your child in a community where they’ll face constant prejudice and danger? Or do you let them go? Give them a chance at a different life, knowing you might never see them again.

The team sat in heavy silence, contemplating the weight of such decisions.

The photograph took on new meaning.

Perhaps it was the only image of Samuel that Thomas and Catherine had been able to keep.

Proof that he had existed, that he had been theirs, even if circumstances eventually forced them apart.

News of the photograph’s discovery and the research surrounding it began spreading through academic circles and then into wider public consciousness.

The museum received dozens of emails from people asking about the family, wanting to know more, offering their own family stories that echoed Thomas, Catherine, and Samuel’s experience.

One email stood out.

It came from a woman named Joyce Turner in Philadelphia, age 76.

She wrote, “My grandmother told me stories about her grandmother, a woman named Catherine, who lived in Charleston after slavery ended.

She said Katherine had raised a child who wasn’t hers by birth, but was hers by choice.

She said the child’s name was Samuel, and that he had traveled far to find peace.

I always wondered what that meant.

When I saw your article about the photograph, I felt I needed to reach out.

” That is Sarah immediately contacted Joyce who agreed to visit the museum and share what she knew.

When she arrived two weeks later, she brought her own family photographs and documents, including a faded tint type of an elderly black woman who Joyce identified as Catherine, probably taken in the 1890s.

My grandmother said that Catherine lived until 1902.

Joyce explained, “She and Thomas stayed in Charleston their whole lives, worked hard, helped establish a church, raised other children, two daughters born in the 1870s.

But she said Catherine always kept one photograph in a special place wrapped in cloth that she would look at sometimes but never showed to anyone.

Joyce reached into her bag and pulled out a small worn piece of fabric yellowed linen with delicate embroidery along the edges.

My grandmother gave this to me before she died.

She said it was what Catherine used to wrap the special photograph.

She told me, “Your great great grandmother loved a child the world didn’t understand, and she never apologized for it.

” Michael carefully examined the fabric under proper lighting.

The dimensions matched the photograph they’d been restoring.

This could have been its original wrapping, kept safe for decades, passed down through generations as a precious family artifact.

Joyce wiped her eyes.

I grew up hearing that our family had complicated history, that there were stories we didn’t talk about outside the family, but my grandmother always said Catherine was the strongest woman she’d ever known, that she’d chosen love when the world expected her to choose bitterness.

Is that photograph? Is that my family? Sarah gently showed Joyce the restored image on a tablet.

Joyce stared at it for a long time, tears streaming down her face, then nodded.

That’s her.

I can see it.

She has the same eyes as my grandmother, the same way of holding her shoulders.

And that baby, that’s the child she loved.

Over the next weeks, Joyce worked with the research team, sharing oral histories passed down through four generations.

She revealed that Samuel had indeed left Charleston around 1876 during the violent collapse of Reconstruction.

Thomas and Catherine had made the painful decision to send him north with members of their church who were relocating to Philadelphia.

They knew he’d have a better chance there.

Joyce explained he could find work, maybe even pass for White if he needed to for safety.

But my grandmother said Catherine cried for months after he left.

She’d sit with that photograph and talk to it like he could hear her.

The family never saw Samuel again, but they received one letter from him in 1883, delivered through an intermediary saying he was alive, working as a clerk, and grateful for everything they’d given him.

He never mentioned if he’d married or had children, and there were no more letters after that.

Joyce looked at the photograph one more time.

She kept his memory alive.

She made sure we knew his story, even when she couldn’t speak his name publicly.

That’s love that survives everything.

Dr.

Mitchell organized a symposium at the museum to contextualize the photograph within the broader history of reconstruction and its aftermath.

Historians, sociologists, and descendants of reconstruction era families gathered to discuss the difficult realities that photographs like this one represented.

Professor David Grant from Duke University presented research on mixed race families in the post-emancipation south.

We estimate that tens of thousands of children were born in circumstances similar to Samuels.

children whose existence testified to the sexual violence inherent in slavery.

After emancipation, these families had to navigate impossible social terrain.

He displayed census data showing the dramatic increase in children listed as mulatto in the late 1860s and 1870s, many living with black families.

These weren’t abstractions.

These were real children who needed homes, love, protection.

And despite everything, despite trauma, despite poverty, despite a society that offered them no support, families like Thomas and Catherine stepped forward.

Dr.

Roberts presented findings on the psychological impact of such circumstances.

We must acknowledge the complexity.

Catherine didn’t choose Samuel’s conception, but she chose to be his mother.

That distinction matters.

She reclaimed agency in a situation designed to deny her any.

That’s resilience, not resignation.

The symposium became emotional when descendants shared family stories.

Many revealed that they too had light-skinned ancestors born in the 1860s whose origins had been whispered about but never openly discussed.

One woman, Margaret Wilson from Atlanta, stood and spoke through tears.

My great great-grandfather was raised by a black family in South Carolina, but he was light enough to pass.

In the 1880s, he moved to Atlanta and lived as a white man.

He married a white woman, had children, and none of them knew his true history until my grandmother found letters after he died.

We’ve carried that secret for generations, ashamed of it.

But seeing this photograph, understanding what families like Thomas and Catherine did, it changes how I see our story.

They love children like my great great-grandfather when no one else would.

Michael completed the full restoration of the photograph, revealing details that had been invisible for 154 years.

The enhanced image showed Catherine’s face with heartbreaking clarity.

She was younger than they’d initially estimated, probably only 25, with eyes that held both determination and sorrow.

Thomas appeared to be in his early 30s, his hand protectively on Catherine’s shoulder.

His expression serious but gentle.

Most significantly, Samuel’s face became clearer.

He was perhaps 3 or four months old in the photograph, and his light skin was undeniable, but so was the tenderness with which Catherine held him, the protective curl of her arms, the way she positioned him close to her heart.

The restored photograph revealed one more detail that stunned everyone.

On Catherine’s dress, barely visible, was a small pin, a simple brass design showing clasped hands, a symbol used by abolitionist societies and later by freed people’s associations to represent solidarity and mutual support.

She was making a statement.

Sarah realized she wore that pin deliberately for this photograph.

She was saying, “This is my family.

This is my choice.

And I stand with those who believe in solidarity and protection for all our people, including this child.

The museum prepared to unveil the restored photograph to the public.

But first, they invited Joyce Turner and other family descendants for a private viewing.

23 people came, descendants of Katherine and Thomas through the two daughters born in the 1870s, spanning five generations.

When the photograph was revealed, displayed 6 feet tall on a gallery wall with its full resolution and detail visible.

The room fell silent.

Then Joyce stepped forward and placed her hand on the image, specifically on Catherine’s face.

Thank you, she whispered.

Thank you for being brave enough to love him.

Thank you for giving him a chance.

The museum opened its exhibition, Families Forged in Freedom, Reconstructions, Hidden Stories, in January 2021.

The photograph of Thomas, Catherine, and Samuel, served as the centerpiece, accompanied by detailed historical context, documents, and oral histories that explained the difficult realities of the period.

The exhibition didn’t shy away from the painful truth of Samuel’s conception.

It acknowledged the sexual violence endemic to slavery while celebrating the love and choice that defined his upbringing.

Wall text explained, “This photograph documents a family built on resilience, choice, and love in the aftermath of unspeakable violence.

It challenges us to recognize both the brutality of our history and the extraordinary humanity of those who survived it.

Visitors came in the thousands, many visibly moved.

Teachers brought students to discuss the complexities of reconstruction.

family stood before the photograph for long minutes, processing its meaning.

The museum installed a comic book where visitors could leave reflections.

One entry read, “My own family never talked about the light-skinned relatives in old photographs.

Now I understand why the silence and why the silence was wrong.

These stories deserve to be told.

” Another wrote, “Thomas was a father to a child who needed one.

That’s what matters.

That’s what love looks like.

” National media covered the exhibition, sparking broader conversations about mixed race heritage and African-American families, sexual violence during slavery, and the chosen families that formed in slavery’s aftermath.

Some coverage was thoughtful and nuanced, some sensationalized.

The museum released a statement emphasizing that this was Samuel’s story, Catherine’s story, Thomas’s story, not a curiosity, but a testimony to survival.

Joyce Turner gave interviews, speaking carefully but honestly, about her family’s history.

Catherine taught us that love is a choice you make every day, especially when circumstances make that choice difficult.

She chose Samuel.

Thomas chose both of them.

That’s our legacy.

One year after the photographs unveiling, the museum hosted a commemoration ceremony.

Descendants gathered again, joined by historians, community members, and others whose families carried similar stories.

A small monument was dedicated at the site in Charleston, where Thomas and Catherine’s home had once stood.

Now just an empty lot in the Hamstead neighborhood.

The monument featured a bronze plaque with a restored photograph engraved into it along with an inscription written collaboratively by family descendants.

Here lived Thomas and Catherine who chose love and family when the world offered them neither.

Here they raised Samuel and built a life of dignity.

May their courage remind us that families are defined not by biology alone but by the love we choose to give and the children we choose to protect.

Dr.

Mitchell gave the dedication speech, her voice carrying across the assembled crowd.

This photograph teaches us that our history is not simple.

It contains violence and love, trauma and resilience, pain and extraordinary grace.

Thomas, Catherine, and Samuel’s story is not comfortable.

It shouldn’t be, but it’s true and it matters.

She gestured to the descendants standing nearby.

These people exist because Catherine chose survival and love.

Because Thomas chose to be a father when he didn’t have to be.

Because Samuel was raised by people who saw his worth despite circumstances designed to deny it.

That’s not a story of shame.

It’s a story of triumph over impossible odds.

Joyce Turner placed flowers at the monument’s base, joined by her children and grandchildren.

Catherine kept that photograph wrapped in cloth for decades, protecting it, protecting Samuel’s memory.

She wanted us to know this story.

She trusted that someday we’d be ready to understand it, to honor it.

Today, we prove she was right.

As the ceremony concluded, a local children’s choir sang hymns that would have been familiar in the African Methodist Episcopal Church where Samuel was baptized.

The voices rose in the winter air, a testimony to continuity and survival.

The photograph remains on permanent display at the museum, a testament to a family that existed in defiance of a society that tried to make their love impossible.

It stands as evidence that in the wreckage of slavery’s aftermath, people found ways to build families, to choose each other, to protect children who needed protection.

Thomas, Catherine, and Samuel’s story isn’t unique.

Thousands of families navigated similar circumstances, made similar choices, carried similar pain and love.

But this photograph gives their experience visibility, documentation, recognition.

It says this happened.

This family existed.

This love was real.

And in museum archives and family albums across the country, other photographs wait.

Other stories of complicated families, chosen bonds, and survival.

Each one a reminder that history is made of individual lives, individual choices, individual acts of love that echo forward through generations.

News

CHINA PUSHED TOO FAR IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA—THEN THE U.S.

NAVY ANSWERED WITH A SHOW OF FORCE THAT TURNED CALM WATERS INTO A HEART-POUDING STANDOFF NO ONE SAW COMING ⚓ What started as a r0ut1ne patr0l m0rphed 1nt0 a h1gh-stakes chess match 0f steel hulls and radar l0cks, sh1ps gl1d1ng cl0ser and cl0ser l1ke predat0rs c1rcl1ng prey, unt1l 0ne b0ld m0ve fl1pped the scr1pt and left c0mmanders gr1pp1ng rad10s, w0nder1ng wh0 w0uld bl1nk f1rst 1n a sea suddenly th1ck w1th tens10n 👇

The Br1nk 0f Catastr0phe: A Clash 1n the S0uth Ch1na Sea In the heart 0f the S0uth Ch1na Sea, tens10n…

$1B CARTEL “MEGA-LAB” VANISHES OVERNIGHT — NAVY SEALs DESCEND IN TOTAL DARKNESS AND BY SUNRISE THERE’S NOTHING LEFT BUT SMOKE, SAND, AND SILENCE 💥 What started as a r0ut1ne bl1p 0n a satell1te feed sp1raled 1nt0 a c1nemat1c m1dn1ght 0perat10n as el1te teams m0ved l1ke gh0sts thr0ugh the c0mp0und, alarms wa1l1ng and l1ghts cutt1ng 0ut 0ne by 0ne, and when the dust settled the emp1re that 0nce pr1nted f0rtunes had s1mply evap0rated, leav1ng l0cals wh1sper1ng that the desert 1tself swall0wed the k1ngp1ns wh0le 👇

Shad0ws 0f the Jungle: The Fall 0f the Emp1re In the depths 0f a jungle, where the sun struggled t0…

“BREAKING: FEDS BLOW THE ROOF OFF MINNEAPOLIS OPERATION — 9,700 LBS OF D*R*G*S, $69 M IN ALLEGED BRIBES, AND VISA SCANDAL EXPOSED IN WHAT LOOKED LIKE AN ORDINARY OFFICE SWEEP 💣” In a m1dn1ght bl1tz that sh0cked ne1ghb0rs and sent sh0ckwaves thr0ugh state p0l1t1cs, agents 1n tact1cal gear t0re thr0ugh sh1pp1ng crates and f1les as 1f chas1ng 1nv1s1ble puppet-masters, unc0ver1ng p1les 0f suspect carg0 and c0ld-hard cash that have l0cal 1ns1ders wh1sper1ng th1s 0perat10n was b1gger than anyth1ng M1nneap0l1s has ever seen 👇

Shad0ws 0f Dece1t: The M1nneap0l1s C0nsp1racy In the heart 0f M1nneap0l1s, the a1r was th1ck w1th tens10n. Agent Carter, a…

FBI & ICE STORM “SOMALI CITY” IN A PRE-DAWN SIEGE—AND WHAT THEY DRAG OUT SHOCKS EVEN SEASONED AGENTS: 2,645 POUNDS OF D*R*G*S, $95M IN CASH, AND WHISPERS OF CJNG SHADOW DEALS 💥 What began as a quiet neighborhood morning detonated into flashing lights and battering rams as black-vested teams poured through doors, uncovering stacks of money and coded ledgers that read like a crime novel, leaving residents peeking through curtains while officials hauled away secrets heavy enough to bend the truth 👇

The Shadows of Somali City In the heart of Somali City, a storm was brewing. Bilon Muhammad Awali, the seemingly…

MIDNIGHT SHOCKWAVE AT MICHIGAN PORT: FBI & ICE STORM THE DOCKS AND UNCOVER 8,500 POUNDS OF D*R*G*S PLUS MOUNTAINS OF CASH STACKED LIKE A CRIME LORD’S TREASURE CHEST 🚢 What l00ked l1ke an 0rd1nary carg0 n1ght suddenly turned c1nemat1c as fl00dl1ghts blasted the darkness and agents swarmed c0nta1ners l1ke ants 0n sugar, r1pp1ng 0pen crates t0 reveal bundles that screamed “s0meth1ng’s wr0ng,” leav1ng l0ngsh0remen fr0zen 1n d1sbel1ef wh1le 0ff1c1als hauled away ev1dence that c0uld bankr0ll a small nat10n 👇

The Gh0st Lane: A P0rt 0f Shad0ws At the break 0f dawn, when the w0rld was st1ll shr0uded 1n the…

BORDER BREACH AT DAWN: SHADOWY CARTEL CONVOYS SLIP THROUGH THE DARK—THEN U.S.

NAVY SEALs DESCEND LIKE GHOSTS AND THE MAP ITSELF SEEMS TO SWALLOW THE THREAT WHOLE 🌵 What began as a quiet desert night explodes into a high-stakes chess match of heat signatures and whispered commands, helicopters slicing the air while elite operators move with eerie calm, and by sunrise the trail goes cold, the convoy gone, leaving locals staring at empty sand and wondering what really happened out there 👇

The Sky’s Reckoning In the heart of a world brimming with tension, Captain Alex Mercer soared through the clouds, piloting…

End of content

No more pages to load