1849.Dgeray found and experts freeze as they zoom in on what the enslaved girl holds.

The dgeraype was discovered in March 2024.

Hidden behind a loose brick in the basement of the Bowont mansion in Charleston, South Carolina.

The house was undergoing extensive restoration after being purchased by a historical preservation society.

A construction worker carefully removing damaged masonry noticed the small wooden box wedged deep into a cavity in the wall.

Inside the box, wrapped in oil cloth that had protected it for over a century, was a single dgeray type in a leather case.

The Preservation Society immediately contacted Dr.

Marcus Webb, chief curator at the Charleston Museum of Southern History and a specialist in antibbellum photography and the history of slavery.

Marcus arrived at the mansion on a humid April morning.

The dgeraype awaited him in a climate controlled room the preservation team had set up for sensitive materials.

He opened the leather case carefully, revealing the image inside.

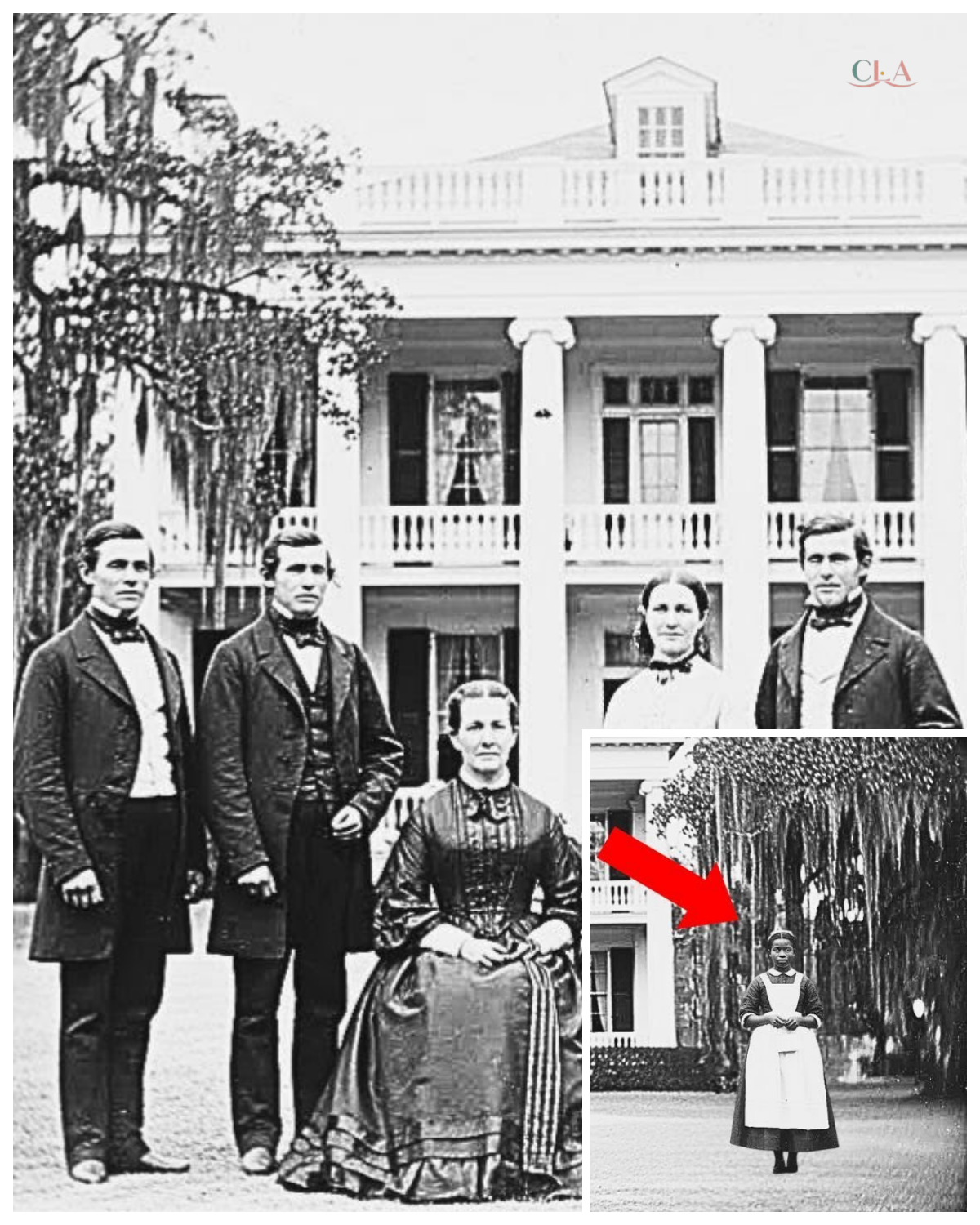

The photograph showed a family of five posing in front of an imposing three-story mansion with tall white columns and wide verandas.

The architectural details were crisp.

The dgeray process, despite its age, had captured remarkable clarity.

Spanish moss hung from live oak trees framing the house.

A cobblestone drive led to the entrance.

The family stood arranged in a formal composition.

A man in his 40s, dressed in an expensive dark suit, stood at the center.

Beside him was a woman in an elaborate silk dress with wide skirts and lace trim.

Three children flanked them.

two boys in suits and a girl in a white dress with ribbons.

Their expressions were serious, as was typical for dgeray types, which required subjects to remain perfectly still for extended exposure times.

Everything about the image spoke of wealth, power, and southern aristocracy in its antibbellum prime.

But it was the figure at the edge of the frame that made Marcus’ breath catch.

Standing to the right, positioned slightly behind and separate from the family, was a young black girl.

She appeared to be about 14 years old, wearing a plain dark dress with a white apron.

the standard uniform of a house servant.

Her posture was rigid, her face expressionless in the way enslaved people had learned to school their features in the presence of white masters.

Marcus had seen hundreds of dgeray types and early photographs from the antibbellum south.

Enslaved people occasionally appeared in them, usually as background figures meant to demonstrate the owner’s wealth, but something about this image felt different.

The girl’s position in the frame seemed deliberate, not incidental.

He carefully removed the dgerotype from its case and carried it to his portable examination station.

Under magnification and proper lighting, he began studying every detail of the image.

Starting with the mansion itself and the white family, documenting everything before turning his attention to the young girl who stood at the edge of their world.

Marcus spent an hour examining the White family and the architectural details of the mansion.

He documented the style of their clothing, which confirmed the 1849 date scratched faintly on the back of the dgerayes case.

He noted the mansion’s Greek revival architecture, typical of wealthy Charleston families in the mid-9th century.

Then he turned his attention to the enslaved girl.

He adjusted his magnifying lamp and began examining her image section by section.

Her face first, young, perhaps 13 or 14, with features that suggested she might be of mixed race, common among enslaved populations due to the widespread sexual violence of slavery.

Her expression was carefully neutral, revealing nothing.

Her clothing was simple but clean, a dark dress, probably dark blue or black, with long sleeves and a high collar.

Over it, a white apron starched and pressed.

Her hair was covered with a white cloth tied neatly at the back of her head.

Standard attire for a house servant in a wealthy family.

Marcus moved his examination down to her hands and suddenly froze.

The girl’s hands were positioned in front of her, holding something against her apron.

At first glance, under normal viewing conditions, the objects were barely visible, dark against the dark fabric of her dress, but under magnification and adjusted lighting, they became unmistakable.

In her right hand, she held a piece of paper, not a small scrap, but a full sheet folded once.

In her left hand, positioned carefully so it would be visible in the photograph.

She held a pencil.

Marcus felt his heart begin to race.

He adjusted the magnification higher, focusing on the paper and pencil.

There was no mistake.

The paper appeared to have writing on it.

He could see faint marks across its surface.

The pencil was clearly a writing instrument held in the proper grip for writing, not just randomly grasped.

He sat back from the examination table, his mind reeling.

In 1849 in South Carolina, it was a crime to teach enslaved people to read or write.

The Negro Act of 1740, still in force, explicitly prohibited literacy education for slaves.

Violation could result in severe punishment for both teacher and student, whipping, branding, or even death for repeated offenses.

Yet, here was an enslaved girl in a formal family dgeraype, openly holding paper, and a writing implement.

The dgeraype process required long exposure times.

Everyone in the image had to remain perfectly still for at least 30 seconds, sometimes longer.

The girl hadn’t accidentally been holding these items when the photographer triggered the exposure.

She had deliberately positioned herself this way and held the pose.

Marcus photographed the dgerotype with his highresolution digital camera, taking multiple shots at different angles and with different lighting.

He uploaded the images to his computer and began enhancing them, adjusting contrast and sharpness to reveal every possible detail.

Under digital enhancement, the paper in the girl’s hand became clearer.

He could now definitely see writing on it lines of text and what appeared to be careful, deliberate handwriting.

The paper wasn’t blank.

She had written something, and she was displaying it for the camera.

Marcus needed to identify who these people were.

The mansion in the photograph was his first clue.

He had extensive knowledge of Charleston’s historic homes, and the architectural style was distinctive.

He began comparing the Dgeray to known Antabbellum mansions still standing in Charleston and to historical photographs and drawings of houses that had been destroyed.

After 3 hours of comparison, he found a match.

The mansion was the Bowmont estate on Meeting Street, the same house where the Dgeray type had been found.

The Preservation Society had historical documentation about the property, which Marcus immediately requested.

The Bumont family had been among Charleston’s wealthiest slaveolding families.

Records showed that Richard Bowmont, born 1805, had inherited the mansion and three rice plantations from his father in 1835.

By 1849, he owned over 300 enslaved people across his various properties.

The 1850 census taken just a year after the dgeray type was made listed the Bowmont household.

Richard Bowmont, age 45, planter, his wife Margaret, age 38, their children, William age 16, James, age 14, and Elizabeth, age 11.

The ages match the family in the photograph.

The census also listed 45 slaves residing at the Charleston mansion itself, separate from the hundreds working the plantations.

These would have been house servants, personal attendants, cooks, stable workers, and others who served the family’s urban residents.

But the census didn’t list enslaved people by name, just by age, sex, and race category.

Marcus found a notation indicating that among the enslaved population at the Charleston house were 12 females under age 20.

The girl in the photograph could have been any of them.

Marcus needed more detailed records.

He turned to the Bumont family papers, which had been donated to the South Carolina Historical Society decades earlier.

The collection included business correspondents, plantation records, household accounts, and personal letters.

In the household accounts from 1849, Marcus found entries listing expenses for the Charleston house slaves.

The records showed purchases of fabric for servants clothing, shoes, food rations, and medical care.

They were listed by first name only: Hannah, Lucy, Dina, Sarah, Martha.

12 female names matching the census count.

But one entry caught Marcus’ attention.

In June 1849, just two months after the dgeray types date, Hannah punishment for forbidden activity, whipping administered, items confiscated.

No further details were provided, but the timing seemed significant.

Had Hannah been the girl in the photograph? Had she been punished for the very act the dgeray type had captured, for knowing how to write, for daring to display that forbidden knowledge? Marcus searched for more references to Hannah in the Bowmont Papers.

What he found next confirmed his suspicion and made his hands tremble with both excitement and horror.

Among Margaret Bowmont’s personal correspondents, Marcus found a series of letters she had written to her sister in Virginia throughout 1849.

The letters were chatty, full of social gossip, complaints about the Charleston heat, and mundane details of household management.

But in a letter dated May 1849, Marcus found a passage that made everything clear.

Dear sister, Margaret wrote, I must tell you of a most disturbing discovery we have made regarding one of our house servants.

You remember Hannah, the mulatto girl who serves Elizabeth? We have discovered that the girl can write.

Can you imagine? Richard is beside himself with fury.

Elizabeth, foolish child, has apparently been teaching Hannah her letters in secret for over a year.

She claims she was only trying to help Hannah read the Bible, as if that makes it acceptable.

The letter continued, “We have, of course, put a stop to this immediately.

Hannah has been severely corrected, and Elizabeth has been confined to her room and forbidden from any unsupervised contact with the servants.

Richard wanted to sell Hannah immediately, but I convinced him the scandal would be too great if word got out that we had allowed such a thing to happen under our own roof.

People would say we were lax in managing our household, so Hannah remains, but under much stricter supervision.

Marcus sat back, his mind racing.

Elizabeth Bowmont, the 11-year-old daughter, had secretly taught her family’s enslaved servant to read and write.

And somehow before the situation was discovered, they had managed to create a photographic record of Hannah’s literacy, a permanent piece of evidence that defied the very laws that governed southern society.

But who had taken the Dgeray type, and why had it been commissioned by the Bumont family as a standard family portrait with Hannah’s inclusion simply meant to show their household’s full composition? Had they not noticed what she was holding, or had someone else arranged for the photograph to be taken, someone who wanted to document what Elizabeth had done, what Hannah had learned? Marcus found more letters.

In June 1849, Margaret wrote, “Elizabeth continues to be difficult about the Hannah situation.

She cries and insists she did nothing wrong, that all people should be able to read God’s word.

Richard has had to speak to her sternly about the natural order and her duty to accept the wisdom of her elders.

She will learn in time that sentiment cannot be allowed to override proper social structure.

” Then in July, a peculiar thing happened yesterday.

Elizabeth asked to see the family dgeray type we had made in April, the one with all of us in front of the house.

When I showed it to her, she stared at it for the longest time, particularly at Hannah’s figure in the corner.

Then she asked if she could keep it in her room.

I saw no harm in it and gave her permission.

The child is still grieving the loss of her friendship with Hannah.

Time will help her understand why such attachments are inappropriate.

Marcus realized what must have happened.

The Dgera type had been a standard family portrait, probably commissioned by Richard to document his wealth and status.

Hannah’s inclusion had been incidental.

She was simply part of the household composition.

But Elizabeth, knowing what she had taught Hannah, had specifically told Hannah to hold paper and pencil for the photograph.

It had been Elizabeth’s secret documentation of their forbidden lessons, hidden in plain sight in a formal family portrait.

Marcus needed to know who had taken the photograph.

Dgeray was still a relatively new and expensive process in 1849.

Only a few photographers operated in Charleston at that time.

He researched photographic studios active in Charleston in the late 1840s and found three possibilities.

The most prominent was George Cook’s studio on King Street.

Cook was known for photographing Charleston’s elite families.

Marcus contacted the Library of Congress which held Cook’s business ledgers and client records as part of their dgerype history collection.

In Cook’s ledger from April 1849, he found the entry Bumont family portrait mansion exterior full plate dgeray type $25.

April 15th, 1849.

$25 was an enormous sum, equivalent to several months wages for a working-class person.

Only the wealthiest families could afford such portraits.

But Cook’s ledgers contained more than just financial records.

He had kept technical notes about his dgeray types, exposure times, lighting conditions, compositional decisions.

For the Bowmont portrait, he had written clear day, good light, family positioned on front steps, exposure 45 seconds.

Note: Young Miss Bowmont insisted servant girl be included in frame.

unusual request, but clients wishes accommodated.

So, Elizabeth had requested Hannah’s inclusion.

Marcus imagined the scene, the photographer setting up his heavy camera equipment, the family arranging themselves on the mansion steps, and 11-year-old Elizabeth insisting that Hannah be part of the portrait.

Her parents had probably thought it was childish whimsy, perhaps even appropriate, showing their servants as part of their prosperous household.

They hadn’t known what Elizabeth had planned.

They hadn’t noticed during the 45se secondond exposure exactly what Hannah was holding.

The dgerayype process created a unique unre repeatable image.

Once the exposure was made, that was the only copy.

If the Bumonts had noticed Hannah’s paper and pencil when they received the finished dgeraype, it would have been too late to undo it.

They would have had to commission an entirely new sitting at additional cost.

Had they noticed? Margaret’s letter suggested they had not, at least not immediately.

The dgeraype had been displayed openly enough that Elizabeth could ask to see it months later.

If Richard had understood what the image truly showed, evidence of his daughter’s crime and his household’s failure to maintain proper control, he surely would have destroyed it.

Marcus found one more crucial piece of information in Cook’s notes.

The photographer had recorded an unusual detail.

Young servant girl stood remarkably still during exposure.

No blur in her portion of image despite long exposure time.

Unusual discipline for one so young.

Hannah had understood the importance of remaining perfectly still.

She had held her pose, paper and pencil clearly visible for 45 seconds.

Long enough for the silver-coated copper plate to capture every detail.

Long enough to create permanent evidence that an enslaved girl in Charleston, South Carolina in 1849 could write.

Marcus returned to the Bowont family papers, searching for more information about what happened to Hannah after her literacy was discovered.

The household accounts told part of the story through their cold transactional language.

June 1849.

Hannah, medical care for injuries, $3.

The entry appeared alongside routine expenses for other servants who had been injured or fallen ill.

But the timing, just weeks after Margaret’s letter describing Hannah’s correction, made clear what kind of injuries required medical care.

Marcus found a letter from Richard Bowmont to his plantation overseer, dated June 1849.

I’m sending the girl Hannah to work at Riverbend Plantation for the remainder of the summer.

She has proven unsuitable for house service and requires harder discipline than can be administered in town.

She is to be put to fieldwork and given no special considerations.

I will decide in the fall whether she returns to Charleston or remains permanently in the fields.

Being sent from house service to fieldwork was one of the most severe punishments an enslaved person could receive.

House servants typically had better food, clothing, and living conditions than field workers.

Field work on a rice plantation was brutal, dangerous labor with high mortality rates.

For a teenage girl who had spent her life in the relatively sheltered environment of urban domestic service, the transition would have been devastating.

Marcus researched the Riverbend Plantation records.

The plantation journals preserved at the South Carolina Historical Society documented the daily operations, including the arrival and assignment of workers.

An entry from July 1849 read, “Received girl Hannah from Charleston House, age approximately 14.

Assigned to second gang for rice cultivation.

Weak constitution unsuited to field labor.

collapsed twice in first week.

Overseer recommends return to domestic service or sale.

Another entry two weeks later, Hannah showing signs of fever.

Move to sick house.

Production loss noted.

Then in August, Hannah recovered sufficiently to return to light duties.

Assigned to children’s quarters to assist nurse.

Better suited to this work than field labor.

Hannah had survived barely.

The rice fields had nearly killed her, but she had endured.

The plantation overseer, recognizing that she was more valuable alive than dead, had reassigned her to work caring for enslaved children.

Still grueling labor, but less immediately life-threatening than working in the flooded rice fields under the brutal summer sun.

Marcus found one more reference to Hannah in the Bowmont Papers.

In September 1849, Richard wrote to Margaret, “I have decided Hannah may return to Charleston, but not to house service.

She will work in the kitchen under strict supervision.

Elizabeth is not to have any contact with her.

The matter is closed.

” Hannah had returned to Charleston, but her life had been irrevocably changed.

She had been punished severely for the crime of literacy.

But had she been broken? Had the punishment destroyed her spirit, or had she somehow maintained the knowledge Elizabeth had given her? Marcus’ next major discovery came from an unexpected source.

While researching Elizabeth Bowmont’s later life, he learned that she had married in 1858 and moved to Virginia with her husband.

She had died in 1923 at age 85.

Her personal papers had been donated to the Virginia Historical Society by her grandchildren in the 1950s.

Marcus contacted the society and requested access to Elizabeth’s papers.

When the digitized materials arrived, he found what he’d been hoping for, Elizabeth’s diary, begun in 1850, when she was 12 years old and maintained with varying frequency until the 1890s.

The early entries were those of a young girl, complaints about lessons, excitement about parties, observations about Charleston society, but interspersed throughout were references to Hannah that revealed the depth of Elizabeth’s guilt and grief over what had happened.

An entry from January 1850.

I saw Hannah today in the kitchen.

She would not look at me.

Mother says I must not speak to her, that I caused enough trouble already.

But I cannot forget that I am the reason she was sent away, the reason she was hurt.

I only wanted to help her.

I thought teaching her to read the Bible was good and Christian.

How can doing good be wrong? March 1850.

I asked father if Hannah could be freed.

He became very angry and said I was to never speak of such things again.

He said, “I’m too young to understand the natural order that negroes are happier when they know their place.

” But Hannah was not happy.

She cried when they took her away.

I hear her crying still in my dreams.

As Elizabeth grew older, her entries became more sophisticated, more critical of the world around her.

In 1852, at age 14, I begin to see the contradictions in everything I have been taught.

We are told in church that all souls are equal before God.

Yet, we treat Negroes as if they have no souls at all.

We are told that slavery is a benevolent institution.

Yet, I saw what happened to Hannah for the crime of learning to read.

How is it benevolent to punish knowledge? In 1856, I will be 18 soon.

Mother is arranging for me to meet suitable young men.

I am expected to marry, to have children, to manage a household with servants of my own.

But I think of Hannah constantly.

She would be 21 now.

Is she still in our kitchen or has father sold her? I dare not ask.

I have learned that asking questions about such things only brings anger and silence.

Then in 1857, Marcus found an entry that made his heart race.

Something extraordinary happened today.

Hannah approached me in the garden, the first time she has voluntarily come near me in 8 years.

She pressed a piece of paper into my hand and walked away before I could speak.

I unfolded it when I was alone.

It was a letter written in a careful, neat hand, Hannah’s hand.

Despite everything they did to her, she has not forgotten how to write.

She has been practicing in secret all these years.

The letter said only this.

Thank you for the gift you gave me.

They can punish my body, but they cannot take away what is in my mind.

I will never forget.

H Elizabeth’s entry continued.

I wept when I read it.

I have kept the letter hidden in my Bible.

Hannah is not broken.

She is stronger than any of us.

And I am ashamed of my weakness, of my silence, of my complicity in this evil system.

Marcus’ research took an unexpected turn when he found references in Elizabeth’s later diary entries to her involvement with abolitionist sympathizers.

In 1858, shortly before her marriage and moved to Virginia, Elizabeth wrote, “I have made contact with friends who work to help those in bondage find freedom.

I cannot do much.

My position is too visible, my family too prominent.

But I have provided money, and I have passed along information when I could do so safely.

It is the least I can do to atone for my cowardice regarding Hannah.

The friends Elizabeth referred to were likely Quakers and other abolitionists who operated the Underground Railroad Network.

Charleston, as a major southern port city, had a small but active underground network helping enslaved people escape to the north.

Marcus contacted the Underground Railroad Research Center in Cincinnati, which maintained extensive records of the network’s operations.

He requested any information about Charleston connections in the late 1850s.

What came back was extraordinary.

Among the records of successful escapes, was an entry from 1859.

Female, approximately 24 years old, literate, formerly enslaved in Charleston household, assisted to Philadelphia via coastal route.

Sponsor: Anonymous female benefactor, Charleston.

subject now residing with Quaker family employed as teacher in Freriedman’s school.

The description matched Hannah’s age in 1859 and the anonymous female benefactor in Charleston could only have been Elizabeth.

Marcus found corroborating evidence in Elizabeth’s diary, an entry from August 1859.

I have done something that would destroy my family if it were discovered.

I helped H escape.

I cannot write the details here even in this private diary.

But she is free now.

She’s in the north and she is teaching others to read.

The knowledge I gave her years ago has multiplied.

She is saving souls through education just as I once dreamed of doing.

I only wish I had the courage to do more.

Marcus researched Freriedman’s schools in Philadelphia in 1859.

He found records of a school operated by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.

Among the teachers listed in their 1860 annual report, was a woman identified only as Miss Hannah, formerly of South Carolina, herself educated through the courage of a young friend who defied unjust laws.

Hannah had not only survived, she had escaped.

She had made it to freedom, and she had dedicated her life to teaching others the very skill that had nearly cost her everything, literacy.

Marcus felt tears in his eyes as he read the evidence.

The dgeray type had captured a moment of extraordinary courage.

A child teaching another child, an enslaved girl holding proof of forbidden knowledge.

And that moment had led to freedom, to survival, to resistance that echoed through generations.

Marcus knew he needed to find out what happened to Hannah after 1860.

He searched through Philadelphia records, looking for any trace of a black woman named Hannah from South Carolina, who had worked as a teacher in the Freriedman school system.

The Civil War complicated his search.

Many records from the early 1860s were lost or destroyed.

But in 1865, after the wars end, he found a marriage record.

Hannah, no surname given, married to a man named Joseph Freeman.

Both described as colored, formerly enslaved, now free citizens.

Marcus traced the Freeman family through subsequent census records.

In 1870, the census listed Joseph Freeman, age 32, laborer, and Hannah Freeman, age 35, teacher, living in Philadelphia with three children.

By 1880, Hannah was listed as principal of a school for colored children.

He found Hannah’s death certificate.

She had died in 1904 at age 69, having spent 45 years in freedom, most of them dedicated to education.

Her obituary in the Philadelphia Tribune, a black newspaper, described her as a pioneering educator who dedicated her life to proving that freed people given opportunity and education could achieve as much as any race.

Mrs.

Freeman often spoke of learning to read as a young girl in Charleston through the kindness of a white child who risked her own safety to teach her.

She called that gift of literacy the foundation of her freedom.

Marcus worked with a genealogologist to trace Hannah’s descendants.

The search led him to dozens of people, teachers, doctors, lawyers, artists, scattered across the United States.

All of them descended from a woman who had once been enslaved, who had been brutally punished for learning to read and who had survived to build a legacy of education and freedom.

He contacted several descendants, explaining what he had found.

One of them, a retired teacher named Grace, living in Philadelphia, agreed to meet him.

Grace brought family materials she had inherited, including letters Hannah had written late in her life to her children and grandchildren.

In one letter written around 1900, Hannah had described her experience in Charleston.

I was a child when Miss Elizabeth taught me my letters.

Hannah wrote, “I did not fully understand the risk she took or the danger I was in.

I only knew that the ability to read felt like magic, like power, like a door opening in my mind.

When they discovered what I knew, they tried to beat that knowledge out of me.

They sent me to the rice fields to break my spirit.

But every day in those fields, I spelled words in my mind.

I traced letters in the mud when no one was watching.

They could control my body, but they could not reach my mind.

That was the gift Miss Elizabeth gave me.

Not just literacy, but the knowledge that my mind was my own, that no one could take my thoughts from me.

Grace showed Marcus a photograph of Hannah taken in the 1880s.

An older woman, dignified and strong, surrounded by students at her school.

Her expression was confident, her posture proud.

This was what Hannah had become.

No longer the frightened girl holding paper and pencil in secret, but a woman who had claimed her freedom and used it to free others through education.

Marcus spent eight months preparing the exhibition.

It would tell Hannah’s story, Elizabeth’s story, and the broader story of forbidden literacy in the antibbellum south.

The dgerayotype would be the centerpiece, but Marcus wanted to provide full context for what the image represented.

He worked with conservators to stabilize and properly display the fragile dgeraype.

He gathered supporting materials, the Bowmont family letters, plantation records, Elizabeth’s diary entries, Cook’s photographic notes, Underground Railroad records, and documents from Hannah’s life in Philadelphia.

The exhibition opened in October 2024 at the Charleston Museum of Southern History.

Marcus had titled it The Gift of Letters: Forbidden Literacy and the Path to Freedom.

The Dgeray Type was displayed in a darkened room with carefully controlled lighting that allowed visitors to see the image clearly while protecting it from damage.

A wall-sized reproduction of the dgeraya type allowed visitors to see details invisible in the original.

Arrows pointed to Hannah’s figure to the paper and pencil in her hands.

Accompanying text explained what they were seeing.

This ordinary family portrait contains evidence of an extraordinary crime.

The young enslaved girl at the edge of the frame holds paper and a writing implement.

Proof that she’d been taught to read and write in violation of South Carolina law.

This single image documents both the brutality of a system that criminalized literacy and the courage of those who defied that system.

The exhibition traced the full story.

Elizabeth’s secret lessons, Hannah’s punishment, her near-death in the rice fields, her survival, her escape to freedom, and her career as an educator.

It showed how one act of childhood compassion, one instance of sharing knowledge across the racial divide had created ripples that extended through generations.

Grace and other descendants of Hannah attended the opening.

They stood before the dgeray type looking at their ancestor as she had been at 14, frightened but defiant, holding proof of forbidden knowledge for a camera that would preserve her courage for 175 years.

The exhibition drew national attention.

News media covered the story of the Dgeray type and what it revealed.

Scholars wrote papers analyzing the image and its historical significance.

Schools incorporated Hannah’s story into their curriculum.

But the most powerful impact was local.

Charleston had long struggled with how to honestly confront its history of slavery.

Many historic sites minimized or romanticized the institution.

The dgerotype made that impossible.

Here was photographic evidence undeniable and permanent of slavery’s cruelty.

A system so threatened by knowledge that it criminalized teaching a child to read.

6 months after the exhibition opened, the city of Charleston installed a historical marker at the site where the Bumont mansion had stood.

The marker told Hannah’s story and honored her courage.

It quoted from one of her letters, “They tried to keep me in darkness, but one child’s kindness gave me light, and I spent my life passing that light to others.

” Marcus stood at the marker’s unveiling, surrounded by Hannah’s descendants and community members.

He thought about the Dgeray, about the moment it had captured.

Elizabeth insisting Hannah be included in the portrait.

Hannah deliberately positioning the paper and pencil where the camera would see them.

45 seconds of absolute stillness that preserved evidence of resistance and hope.

The Dgeray type had survived 175 years, hidden behind a brick, waiting to tell its story.

Hannah had survived, too, had escaped, had thrived, had built a legacy that lasted through five generations.

And Elizabeth, despite her privilege and complicity in the slave system, had acted with courage when it mattered most, had helped free the girl she had once taught, and had carried guilt and determination through her long life.

The image was no longer just a dgera type.

It was testimony.

It was evidence.

It was proof that even in the darkest systems of oppression, human kindness and courage could create cracks that would eventually bring the whole structure down.

Hannah’s hands, holding paper and pencil in defiance of laws meant to keep her in ignorance, had reached across nearly two centuries to teach one final lesson.

That knowledge is freedom, that resistance matters, and that no injustice, no matter how powerful, can ultimately suppress the human spirit’s hunger for truth and dignity.

News

🌲 IDAHO WOODS HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES DURING SOLO TRIP — TWO YEARS LATER FOUND BURIED UNDER TREE MARKED “X,” SHOCKING AUTHORITIES AND LOCALS ALIKE ⚡ What started as a quiet getaway turned into a terrifying mystery, as search parties scoured mountains and rivers with no trace, until hikers stumbled on a single tree bearing a carved X — and beneath it, a discovery so chilling it left investigators frozen in disbelief 👇

In August 2016, a pair of hikers, Amanda Ray, a biology teacher, and Jack Morris, a civil engineer, went hiking…

⛰️ NIGHTMARE IN THE SUPERSTITIONS: SISTERS VANISH WITHOUT A TRACE — THREE YEARS LATER THEIR BODIES ARE FOUND LOCKED IN BARRELS, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE COMMUNITY 😨 What began as a family hike into Arizona’s notorious mountains turned into a decade-long mystery, until a hiker stumbled upon barrels hidden in a remote canyon, revealing a scene so chilling it left authorities and locals gasping and whispering about the evil that had been hiding in plain sight 👇

In August of 2010, when the heat was so hot that the air above the sand shivered like coals, two…

⚰️ OREGON HORROR: COUPLE VANISHES WITHOUT A TRACE — 8 MONTHS LATER THEY’RE DISCOVERED IN A DOUBLE COFFIN, SHOCKING AN ENTIRE TOWN 🌲 What began as a quiet evening stroll turned into a months-long nightmare of missing posters and frantic searches, until a hiker stumbled upon a hidden grave and police realized the truth was far darker than anyone dared imagine, leaving locals whispering about secrets buried in the woods 👇

On September 12th, 2015, 31-year-old forest engineer Bert Holloway and his 29-year-old fiance, social worker Tessa Morgan, set out on…

🌲 NIGHTMARE IN THE APPALACHIANS: TWO FRIENDS VANISH DURING HIKE — ONE FOUND TRAPPED IN A CAGE, THE OTHER DISAPPEARS WITHOUT A TRACE, LEAVING INVESTIGATORS REELING 🕯️ What started as an ordinary trek through the misty mountains spiraled into terror when search teams stumbled upon one friend locked in a rusted cage, barely alive, while the other had vanished as if the earth had swallowed him, turning quiet trails into a real-life horror story nobody could forget 👇

On May 15th, two friends went on a hike in the picturesque Appalachian Mountains in 2018. They planned a short…

📚 CLASSROOM TO COLD CASE: COLORADO TEACHER VANISHES AFTER SCHOOL — ONE YEAR LATER SHE WALKS INTO A POLICE STATION ALONE WITH A STORY THAT LEFT OFFICERS STUNNED 😨 What started as an ordinary dismissal bell spiraled into candlelight vigils and fading posters, until the station doors creaked open and there she stood like a ghost from last year’s headlines, pale, trembling, and ready to tell a truth so unsettling it froze the entire room 👇

On September 15th, 2017, at 7:00 in the morning, 28-year-old teacher Elena Vance locked the door of her home in…

🌵 DESERT VANISHING ACT: AN ARIZONA GIRL DISAPPEARS INTO THE HEAT HAZE — SEVEN MONTHS LATER SHE SUDDENLY REAPPEARS AT THE MEXICAN BORDER WITH A STORY THAT LEFT AGENTS STUNNED 🚨 What began as an ordinary afternoon spiraled into flyers, helicopters, and sleepless nights, until border officers spotted a lone figure emerging from the dust like a mirage, thinner, quieter, and carrying answers so strange they turned a missing-person case into a full-blown mystery thriller 👇

On November 15th, 2023, 23-year-old Amanda Wilson disappeared in Echo Canyon. And for 7 months, her fate remained a dark…

End of content

No more pages to load