More than five millennia ago, a man died alone in the high Alps, his body slowly sealed by snow and ice.

Time should have erased him completely.

Instead, nature preserved him with astonishing precision, turning his remains into one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever made.

When modern science finally uncovered his frozen body in 1991, the world met Ötzi the Iceman—a man whose life, death, and genetic legacy would challenge long-held assumptions about Europe’s ancient past and about humanity itself.

The discovery happened by chance.

While hiking through the Ötztal Alps near the border of Austria and Italy, two German hikers noticed what appeared to be a human body emerging from melting glacial ice.

At first, authorities assumed it was a modern climber who had recently died.

Only after closer inspection did the truth become clear.

The clothing, tools, and physical condition of the body did not belong to the modern world.

Radiocarbon dating soon revealed the staggering reality: the man had lived and died more than 5,300 years ago, during the Copper Age.

He was later named Ötzi, after the valley where he was found.

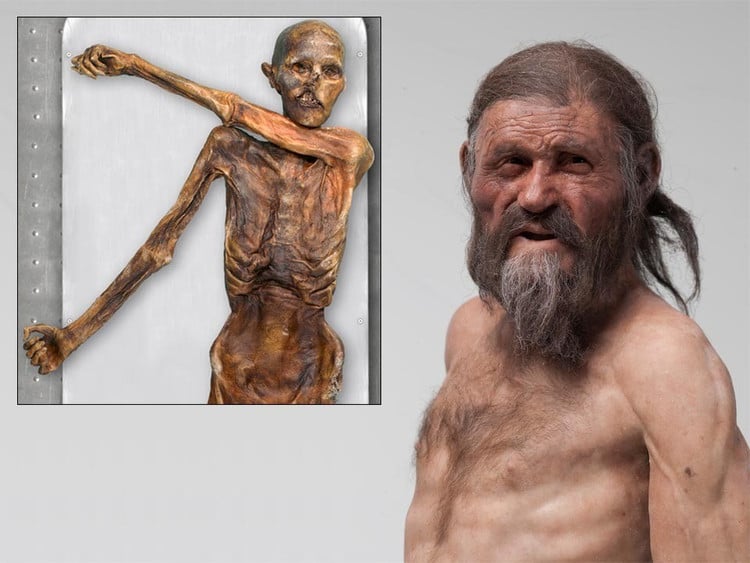

Ötzi’s preservation was extraordinary.

His skin, though darkened and leathery, remained intact.

His facial features were recognizable.

Even his internal organs survived in a state that allowed scientists to study his last meals, his illnesses, and the stresses his body endured.

This level of preservation transformed him into a time capsule, offering a direct and intimate view of life in prehistoric Europe—something archaeologists rarely experience.

The objects found with him painted a vivid picture of his world.

He wore carefully constructed clothing made from animal hides and plant fibers, designed for warmth and mobility in harsh alpine conditions.

His shoes were insulated with grass, a simple but effective solution against cold ground.

He carried a flint knife, a longbow, arrows, and, most striking of all, a copper axe.

At the time, copper tools were rare and valuable, suggesting that Ötzi was not an ordinary man.

The axe alone implied access to resources, skills, or status that set him apart within his community.

Forensic analysis revealed that Ötzi was about 45 years old when he died—an advanced age for his era.

His body showed the marks of a hard life.

His joints were worn from constant movement over rugged terrain.

His muscles reflected endurance rather than strength built for short bursts.

He was not large by modern standards, but his physique was perfectly adapted to survival in the mountains.

Yet beneath this resilience lay signs of constant suffering.

One of the most striking features on his body was a series of 61 tattoos.

Unlike modern tattoos meant for decoration or identity, Ötzi’s markings were functional.

They appeared as simple lines and dots, placed deliberately near joints and along his spine.

Later analysis revealed that many of these locations correspond closely to acupuncture points recognized in traditional medicine thousands of years later.

Chemical analysis of the tattoo pigment suggested the presence of charred plant material with medicinal properties.

This strongly indicates that the tattoos were part of a therapeutic practice, intended to relieve chronic pain from arthritis and physical strain.

Ötzi’s skin, in effect, became a medical record etched into his body.

Despite his careful preparation for survival, Ötzi’s life ended violently.

For a long time, researchers debated whether he died from exposure or exhaustion.

That idea collapsed when advanced imaging revealed an arrowhead embedded deep in his left shoulder.

The arrow severed a major artery, causing rapid blood loss.

The shaft had been removed, either during the attack or afterward, suggesting deliberate action.

Additional injuries on his hands and body pointed to a struggle shortly before his death.

Blood traces from multiple individuals found on his equipment hinted at a complex and violent encounter.

Ötzi was not simply unlucky; he was attacked, hunted, or betrayed.

Where he died raised further questions.

His body lay high in the mountains, far from any permanent settlement.

This suggested that he was either fleeing danger or traveling urgently through dangerous terrain.

His last meals, rich in fat and protein, indicated preparation for intense physical effort.

Everything about his final hours pointed to a man under threat.

As scientific techniques advanced, researchers turned their attention to Ötzi’s DNA, hoping it would reveal where he came from and how he fit into the broader story of human history.

Early genetic studies, conducted in the early 2010s, were groundbreaking for their time.

They suggested that Ötzi had light skin, light eyes, and carried genetic markers associated with later Indo-European populations.

These findings attracted enormous attention because they appeared to push back the timeline of major migrations into Europe.

However, ancient DNA research is extremely delicate.

The risk of contamination from modern DNA is high, especially in early studies when safeguards were less refined.

As sequencing technology improved, scientists revisited Ötzi’s genome using stricter methods and better sampling techniques.

This second, more accurate analysis overturned many of the earlier conclusions.

The revised genome revealed that Ötzi had dark skin and brown eyes, challenging decades of popular reconstructions.

Genetic markers also showed that he was already balding during his lifetime.

More importantly, the supposed Indo-European or “steppe” ancestry vanished entirely.

It had never existed.

The earlier result was caused by contamination, not prehistoric migration.

Instead, the new data revealed a far more unexpected story.

Over 90 percent of Ötzi’s ancestry traced back to Neolithic farmers from Anatolia, in what is now Turkey.

These were among the first people to bring agriculture into Europe thousands of years before Ötzi’s time.

The remaining portion of his DNA came from Europe’s ancient hunter-gatherers.

What made this remarkable was how little his lineage had mixed with later populations.

While much of Europe experienced repeated waves of migration and genetic blending, Ötzi’s ancestors remained unusually isolated.

This isolation meant that Ötzi was not a direct ancestor of most modern Europeans.

His genetic line largely disappeared from the mainland.

Surprisingly, his closest living genetic relatives today are found not in the Alps, but on the island of Sardinia.

Because of its geographic isolation, Sardinia preserved genetic patterns that were overwritten elsewhere in Europe.

Through this connection, Ötzi became a representative of a nearly vanished branch of humanity.

His DNA also revealed something deeply human: he carried genetic risks for heart disease, diabetes, and obesity.

He was lactose intolerant.

He suffered from parasites, gallstones, and Lyme disease—the oldest confirmed case ever identified.

These findings shattered the romantic idea that ancient life was healthier or simpler.

Ötzi’s world was harsh, and his body paid the price.

Disease, pain, and degeneration were already part of the human experience thousands of years ago.

Taken together, Ötzi’s remains tell a story far richer than that of a frozen corpse.

He was a man shaped by migration, isolation, innovation, and vulnerability.

He lived at a crossroads of human history, when farming societies were reshaping Europe, yet his own lineage would soon fade away.

His people survived for generations in difficult terrain, preserving their genetic identity, but that same isolation may have made them fragile in the face of change.

Ötzi’s death froze a moment in time, but science has slowly thawed the truth.

Each new discovery has peeled away assumptions and replaced them with evidence, even when that evidence challenges comforting narratives.

He was darker-skinned than imagined, sicker than expected, and more genetically isolated than anyone predicted.

His story reminds us that the past is not static.

It changes as our tools improve and our willingness to question old conclusions grows.

In the end, Ötzi stands not just as an archaeological marvel, but as a mirror.

His life reflects humanity’s enduring struggle with illness, violence, adaptation, and survival.

His death speaks of danger and conflict that feel disturbingly familiar.

And his DNA shows how entire branches of humanity can rise, endure, and vanish, leaving behind only fragments—sometimes frozen in ice, waiting thousands of years to be found.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load