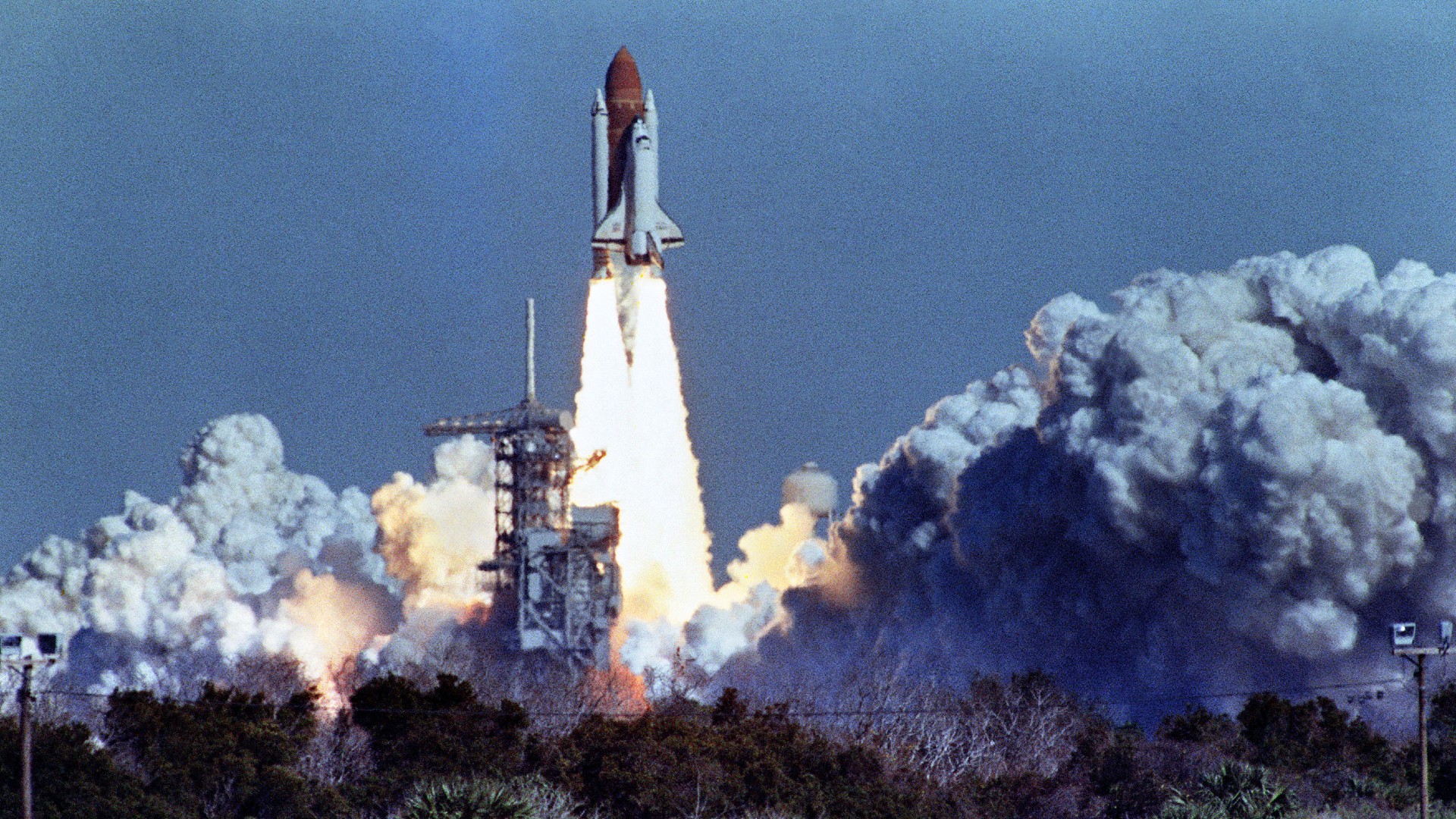

On January 28, 1986, the United States witnessed one of the most devastating moments in the history of space exploration.

The Space Shuttle Challenger broke apart just seventy three seconds after liftoff, leaving seven astronauts lost in a disaster broadcast live to millions.

The event stunned viewers across the nation and reshaped the future of the American space program.

Decades later, the tragedy remains a defining chapter in aerospace history, marked by technical failure, human loss, and lasting reform.

The morning of the launch at Cape Canaveral began with anticipation.

The sky above Florida was clear and bright, though unusually cold for the region.

Families gathered near the launch site, wrapped in jackets against the sharp air.

Across the country, classrooms rolled in televisions so students could watch history unfold.

This mission, designated STS 51 L, carried special significance because it included Christa McAuliffe, a high school teacher selected through the Teacher in Space program.

Her presence symbolized a bridge between NASA and ordinary citizens, turning the launch into a shared national moment.

The crew consisted of Commander Francis Scobee, Pilot Michael Smith, Mission Specialists Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, and Ronald McNair, along with Payload Specialist Gregory Jarvis.

They represented experience, technical expertise, and a collective spirit of exploration.

Few spectators realized that engineers had raised concerns about the cold weather affecting components of the right solid rocket booster.

Specifically, rubber O ring seals inside the booster joints were not designed for such low temperatures.

In cold conditions, these seals could lose flexibility, reducing their ability to prevent hot gases from escaping during ignition.

Despite these concerns, the launch proceeded at 11:38 a.m.Eastern Time.

The shuttle rose from the pad in a cloud of steam and fire, climbing steadily into the blue sky.

For just over a minute, everything appeared normal.

Then, without warning, a brilliant flash erupted.

The shuttle disintegrated in a plume of smoke and flame, leaving two twisting trails from the solid rocket boosters arcing away in opposite directions.

At first, confusion reigned.

Some observers thought the explosion might be part of stage separation.

Within moments, however, the reality became undeniable.

Inside Mission Control in Houston, telemetry data froze and communication ceased.

Controllers maintained composure, but the gravity of the situation was evident.

Recovery operations began almost immediately.

The U.S.Coast Guard and Navy dispatched ships and helicopters to the area where debris fell into the Atlantic Ocean.

What had begun as a rescue effort soon became a recovery mission.

The explosion occurred at approximately 48,000 feet.

Debris scattered across miles of ocean.

Surface vessels collected floating fragments, including pieces of insulation, wiring, and sections of the orbiter skin.

Sonar equipment scanned the seabed for larger components.

Divers entered cold, murky waters with limited visibility, marking and retrieving wreckage piece by piece.

Over time, more than 100 tons of material were recovered, nearly half the shuttle mass.

For weeks, one crucial element remained missing: the crew compartment.

On March 7, 1986, sonar detected a large object partially buried in sand about eighteen miles east of Cape Canaveral.

Divers descending to investigate discovered the shattered but largely intact crew cabin.

The structure had separated from the rest of the orbiter during the breakup and continued upward briefly before descending in a long arc.

It ultimately struck the ocean at tremendous speed, generating forces far beyond survivability.

The recovery of the cabin was conducted with solemn precision.

Once transported to Kennedy Space Center, it was placed in a secure hangar for examination.

Investigators determined that the cabin had remained intact after the initial breakup, rising to roughly 65,000 feet before falling for nearly three minutes.

The final ocean impact was catastrophic.

Within the cabin, recovery teams located what NASA later described as crew remains.

Out of respect for the families, detailed descriptions were never publicly released.

The recovery and identification process was carried out under strict protocols.

Forensic specialists relied on dental records and other medical documentation, as DNA testing was not yet widely available in 1986.

By April of that year, all seven astronauts had been officially identified.

Subsequent biomedical analysis concluded that the precise moment of de*th could not be determined with certainty.

The rapid depressurization of the cabin likely caused loss of consciousness within seconds.

The impact with the ocean, however, was unquestionably fatal.

Families were given the choice of private burial arrangements.

Remains that could not be individually distinguished were cremated together and later interred at Arlington National Cemetery in a private ceremony.

As recovery operations progressed, attention turned to understanding how such a catastrophe could occur.

An independent investigative body known as the Rogers Commission was established to determine the cause.

The commission included respected figures from science and aviation, tasked with examining both technical and organizational factors.

The technical cause was traced to the right solid rocket booster field joint.

The joint was sealed by two rubber O rings designed to prevent hot combustion gases from escaping during ignition.

The unusually cold temperature on launch morning caused the O rings to stiffen, delaying their ability to form a proper seal.

Video footage revealed a small puff of black smoke shortly after liftoff, indicating that the seal had failed.

As the shuttle ascended, hot gases burned through the weakened joint, eventually breaching the external fuel tank.

The resulting structural breakup destroyed the orbiter.

The commission uncovered deeper issues beyond the physical failure.

Engineers from the contractor responsible for the boosters had expressed concern the night before launch about the low temperatures.

Data from previous missions suggested increased O ring erosion in colder conditions.

Some engineers recommended postponing the launch.

However, communication breakdowns and managerial pressure contributed to the decision to proceed.

The final report criticized flawed decision making, inadequate safety oversight, and a culture that discounted engineering warnings.

The findings led to sweeping reforms within NASA.

Booster joints were redesigned with additional seals and heaters to ensure flexibility in cold conditions.

Decision making protocols were revised to give greater authority to safety officials and engineers.

The shuttle fleet was grounded for more than two years while changes were implemented.

When flights resumed in 1988 with the launch of Space Shuttle Discovery, the event was marked by remembrance.

The names of the Challenger crew were read aloud, and a moment of silence honored their sacrifice.

The disaster had permanently altered NASA culture, embedding caution and accountability into its operations.

Public memory of Challenger extended far beyond engineering reforms.

Christa McAuliffe became a symbol of inspiration for students nationwide.

Though the Teacher in Space program was not revived, educational outreach initiatives expanded in her honor.

Schools across the country incorporated lessons about space exploration, risk, and perseverance into their curricula.

At Kennedy Space Center, the Space Mirror Memorial was updated to include the Challenger crew.

Each year on January 28, NASA personnel gather quietly to commemorate the anniversary.

The ceremonies are simple and reflective, emphasizing remembrance over spectacle.

The recovered shuttle components remain stored in a secure facility, preserved for study and historical record.

The Challenger tragedy underscored the inherent risks of human spaceflight.

It revealed how small technical vulnerabilities, combined with organizational misjudgment, can lead to catastrophic outcomes.

The disaster also demonstrated the importance of transparency and independent review in high risk endeavors.

In the years that followed, NASA continued to advance space exploration, applying lessons learned from Challenger to improve safety and reliability.

While space travel remains complex and challenging, the reforms instituted after 1986 have influenced spacecraft design and risk management practices worldwide.

The legacy of Challenger is therefore twofold.

It is a story of profound loss, remembered through the lives of seven individuals dedicated to exploration.

It is also a story of institutional change, showing how tragedy can prompt reflection and reform.

The images of that January morning remain etched in collective memory, a reminder of both the promise and the peril of reaching beyond Earth.

Four decades later, the events of January 28, 1986 continue to be studied in engineering classrooms and management seminars.

The disaster serves as a case study in communication, ethics, and responsibility.

It reinforces the principle that technical expertise must be respected and that safety concerns require careful consideration, regardless of schedule or public expectation.

The Space Shuttle Challenger may have been lost in the Atlantic, but its impact endures in policies, memorials, and the continuing pursuit of knowledge.

The story remains a solemn chapter in aerospace history, reminding future generations that exploration demands not only courage, but vigilance and humility as well.

News

Apollo 11 Astronaut Reveals Spooky Secret About Mission To Far Side Of The Moon! 10t

The Apollo 11 mission remains one of humanity’s greatest achievements, a defining moment when human beings first set foot on…

Bruce Lee’s Daughter in 2026: The Last Guardian of a Legend 10t

As a child, Shannon Lee would sometimes respond to playground bravado with quiet certainty. When other children joked that their…

Selena Quintanilla Died 30 Years Ago, Now Her Husband Breaks The Silence Leaving The World Shocked 10t

Thirty years have passed since the world lost one of Latin music’s brightest stars, yet the name Selena Quintanilla continues…

Scientists New Plan To Retrieve the Titanic Changes Everything! 10t

More than a century after the RMS Titanic slipped beneath the icy waters of the North Atlantic, the legendary ocean…

Drunk Dancer Challenged Michael Jackson — His Response Stunned 80,000 Fans

July 16th, 1989, Wembley Stadium. 80,000 people watched as a drunk backup dancer stumbled onto the stage during Billy Jean…

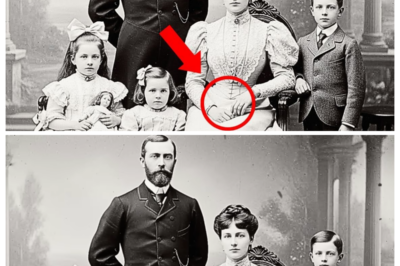

1890 Family Portrait Discovered — And Historians Recoil When They Enlarge the Mother’s Hand

This 1890 family portrait is discovered, and historians are startled when they enlarge the image of the mother’s hand. The…

End of content

No more pages to load