Beneath the stormy, gray waters off Ireland’s northwest coast lies a graveyard unlike any other—a vast underwater cemetery where the remnants of Germany’s defeated submarine fleet from World War II rest, largely forgotten.

Official accounts describe this as a simple, final act: after the war, the Allies rounded up hundreds of surrendered German submarines and sank them in the North Atlantic.

Operation Deadlight, as it was called, seemed like a tidy ending to the deadliest submarine campaign in history.

But recent investigations reveal a far more complicated and dangerous story, one that has been quietly unfolding beneath the waves for more than eight decades.

The operation itself was immense.

In the months following Germany’s surrender in 1945, the British Royal Navy oversaw the disposal of 116 captured submarines, towing them from ports in Northern Ireland and Scotland to a designated scuttling zone off Malin Head.

The task was urgent: winter storms made timing critical, and speed was prioritized over caution or thoroughness.

These were not empty vessels.

Most still carried torpedoes, mines, ammunition, fuel, and battery acid.

Electrical systems contained mercury, while hydraulic systems, oils, and other industrial chemicals remained onboard.

Few submarines were fully inspected before they sank.

In their haste to remove the fleet, the Allies inadvertently created one of the largest underwater toxic zones in the world.

The story becomes even more troubling when we consider U-234, a Type XB submarine captured in May 1945.

Unlike the other submarines, U-234’s cargo was extraordinary.

She carried 560 kilograms of uranium oxide—enough to fuel multiple atomic bombs—alongside technical drawings for advanced German weaponry, jet aircraft components, and radar technology, as well as two Japanese officers en route to Japan to oversee the transfer of this material.

The submarine surrendered to American forces before it could complete its mission.

Its uranium cargo was seized and sent to the Manhattan Project, illustrating that the Germans had been actively transporting nuclear materials and advanced technology by submarine.

This singular event raises a chilling question: what about the other submarines that sank during Operation Deadlight? Could some of them have carried similar or even more dangerous cargo? The truth is, no one knows.

The wrecks lie in water shallow enough—between 30 and 150 meters—to be disturbed by modern fishing trawlers.

For decades, Irish and British fishermen have dragged their nets across the graveyard, occasionally snagging debris that required intervention by bomb disposal teams.

Explosives that might have failed to detonate during the war are now far more unstable after decades underwater.

TNT, Torpex, and other compounds have degraded into crystalline structures sensitive to friction and shock.

A fishing net striking a corroded torpedo tube could trigger an explosion.

Across Europe, bomb disposal units respond to hundreds of incidents each year involving World War II munitions dredged from the seabed.

The North Atlantic, once merely a battlefield, has become an underwater minefield, and the Deadlight zone sits at its center.

The environmental consequences are equally alarming.

Corroding hulls leak diesel fuel, lubricants, sulfuric acid, lead, and mercury into the surrounding waters.

Studies of other World War II wrecks reveal persistent contamination zones where heavy metals enter the food chain, bioaccumulating in fish, shellfish, and other marine life.

Over decades, this process spreads toxins into commercial fisheries, potentially impacting human health.

Unlike better-studied regions such as the Baltic Sea or the Mediterranean, the Deadlight zone has never been systematically surveyed.

Its environmental legacy remains largely invisible, unmonitored, and growing worse every year.

The scale of the problem is staggering when viewed in historical context.

During the war, Nazi Germany built more than 1,150 U-boats, and at the height of the Battle of the Atlantic, over 400 were operational simultaneously.

They hunted in coordinated wolf packs, devastating Allied shipping and sending over 14 million tons of cargo to the ocean floor.

For the sailors of the Allies, the human cost was nearly 30,000 lives lost.

German crews fared no better; submarine service was the deadliest assignment in the German military, claiming roughly 28,000 men.

When Germany surrendered in May 1945, the Allies were suddenly faced with an immense logistical challenge: what to do with hundreds of enemy submarines, many of them technologically advanced and loaded with dangerous cargo.

Dismantling these submarines properly would have required months of labor, dry dock access, and specialized expertise to remove hazardous materials safely.

Sinking them, by contrast, was fast and simple—just a few hours with a deck gun.

The decision to scuttle the fleet quickly, rather than carefully inspect each vessel, created an immense blind spot.

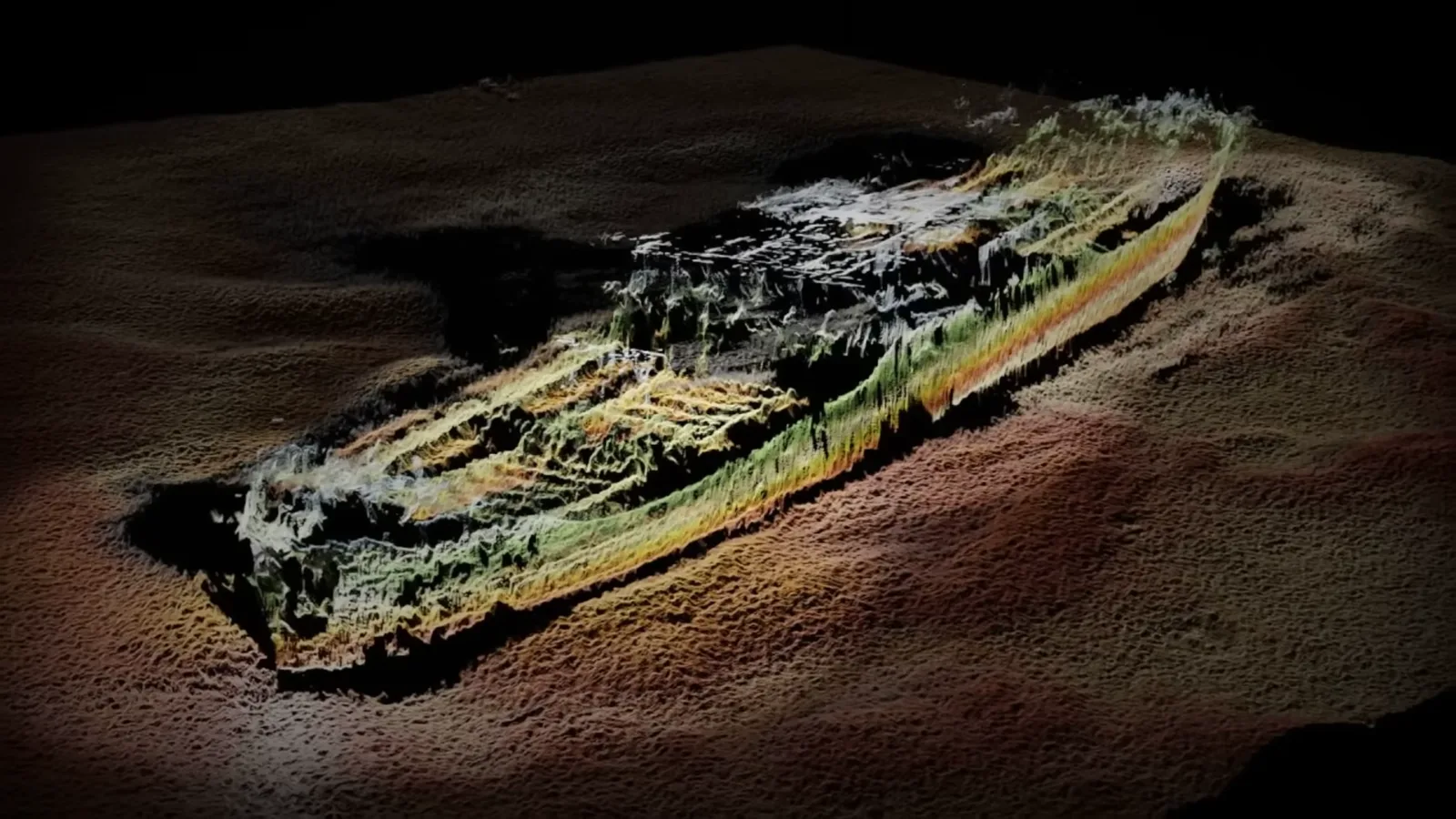

The final positions of many submarines were estimated, not confirmed, and several sank before reaching their intended destinations due to storms, broken tow lines, or hull failures.

Official logs provide an incomplete picture, and decades later, many of the wrecks remain unlocated or unverified.

Beyond explosives, the Deadlight submarines carried a toxic cocktail of industrial materials.

Lead-acid batteries, containing hundreds of kilograms of lead and sulfuric acid, sat in their lower compartments.

Mercury-filled switches, diesel fuel, hydraulic fluids, and other chemicals have been slowly leaching into the environment for decades.

Sediment sampling around other World War II wrecks demonstrates that contamination spreads far beyond the hull itself, entering the food chain and creating persistent ecological hazards.

Heavy metals and hydrocarbons bioaccumulate, affecting fish populations, seabirds, and even humans who consume seafood.

The Deadlight zone is, in many ways, a ticking ecological time bomb, largely ignored because of its location, cost, and the technical challenges involved.

The Deadlight fleet also demonstrates the risks of human oversight and historical accident.

U-234’s capture was fortuitous; had the surrender occurred two weeks earlier, its uranium cargo might have reached Japan, potentially altering the course of the Pacific war.

Other submarines that went down unobserved might have carried similarly hazardous materials.

U-864, sunk off Norway in 1945, was discovered in 2003 still leaking 65 tons of liquid mercury into the surrounding seabed, requiring over $100 million and years of containment efforts.

Multiply that risk across 116 submarines, many of which remain unexamined, and the scale of potential danger becomes apparent.

Modern technology could address these unknowns.

Autonomous underwater vehicles can map seabeds in high resolution.

Remote-operated vehicles can inspect hulls, document corrosion, and sample sediments for contamination.

Sidescan sonar provides detailed imaging without disturbing wrecks.

Yet, despite the capacity for comprehensive investigation, no coordinated effort exists.

Jurisdictional disputes, cost concerns, and competing priorities leave the Deadlight zone largely unmonitored.

Ireland, the UK, Germany, and international maritime bodies each have a stake, yet responsibility is diffuse.

In contrast, other regions have undertaken extensive collaborative surveys and remediation projects; the Atlantic graveyard remains neglected.

The consequences of inaction are imminent.

Corrosion progresses unevenly.

Steel hulls that have remained intact for 80 years may fail suddenly, releasing explosive compounds, toxic metals, and other hazardous materials all at once.

Every day, fishing trawlers disturb the seabed, dragging nets across wrecks, increasing the risk of accidental detonations.

Environmental contamination continues, bioaccumulating through the food chain with unknown long-term effects.

Unlike a ticking clock that counts down predictably, these processes are erratic and potentially catastrophic.

The longer the submarines remain unmonitored, the greater the chance that one day a seemingly minor disturbance could trigger a chain reaction of explosions or widespread pollution.

The Deadlight fleet is not just a relic of history; it is a persistent, growing threat.

Its story combines the drama of war, the failures of postwar bureaucracy, and the hazards of underwater decay.

From the uranium aboard U-234 to the mercury-laden U-864, the past is still influencing the present.

The Allies’ rush to dispose of these submarines created a temporary solution but also left a legacy of unanswered questions, hidden dangers, and environmental risk.

The clock is running out, and the time to act may be now.

Ultimately, the Deadlight zone reminds us that the consequences of war do not end with treaties or peace accords.

The oceans, which once served as theaters of conflict, remain archives of human decisions—decisions that continue to impact ecosystems, communities, and safety decades later.

Whether through corroding torpedoes, leaking industrial materials, or unseen radioactive cargo, the submarine graveyard off Ireland’s coast is a slow-motion disaster that demands attention.

The challenge now is not just historical curiosity; it is public safety, environmental stewardship, and the urgent need for international cooperation to understand and mitigate one of the largest and least studied underwater legacies in modern history.

The questions are clear: What else lies within these sunken submarines? How far has contamination spread? And when will the inevitable failures occur? As the steel hulls corrode and the chemical reactions accelerate, the answers will emerge—whether humanity is ready or not.

For now, the Deadlight fleet remains a silent, rusting warning beneath the waves, a reminder that some legacies refuse to remain buried.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load