For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has remained an enigma that fascinates both believers and scientists.

This fourteen-foot-long linen cloth, slightly more than three feet wide, carries the faint image of a man, front and back, as if a body had rested on it and then vanished, leaving only a spectral imprint.

The marks on the cloth suggest wounds consistent with crucifixion: nail marks on the wrists, a bloodlike stain at the feet, an oval stain on the side suggesting a spear thrust, and faint circles that could represent a crown of thorns.

The face itself is quiet, eyes closed, hair parted and falling in strands that seem to hover above the surface.

For centuries, the cloth has defied easy explanation, resisting both religious interpretation and scientific scrutiny.

The first recorded public display occurred in France in the 13th century, drawing pilgrims, curiosity seekers, and critics alike.

Over time, the Shroud passed through various hands and locations until the House of Savoy brought it to Turin in 1578, where it has remained, surviving fire, smoke, and rescue.

Today, it rests under climate-controlled glass in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, carefully preserved yet still impenetrably mysterious.

The modern scientific fascination with the Shroud began in 1898 when lawyer Secondo Pia photographed it.

The developed negatives revealed something astonishing: the faint image on the cloth appeared as a clear, detailed portrait in the photographic negative.

Cheekbones, lips, hair strands, and hand positions emerged with clarity.

This revelation confirmed that the image interacted with light in unusual ways, challenging assumptions about ordinary pigments or painting techniques.

The Shroud had moved from sacred relic to scientific puzzle.

Throughout the twentieth century, researchers subjected the cloth to increasingly precise examinations.

Chemists analyzed fibers, forensic specialists studied bloodlike stains, and textile historians scrutinized the weave, which matches methods known in the ancient Levant.

Pollen research indicated grains consistent with the region, though none of these results could conclusively prove its origin.

The Shroud’s image behaved unlike any known artwork: the discoloration was superficial, affecting only the outermost fibrils of the threads.

No brush strokes, pigments, or binders were found.

Measurements suggested a relationship between image darkness and the distance from the body’s surface, implying that some form of depth information might be encoded in the cloth.

Attempts to reproduce this effect through heat, chemicals, or other methods came close but never perfectly matched the Shroud’s unique characteristics.

In 1988, radiocarbon dating seemed poised to resolve the question of age.

Samples from a corner of the cloth were tested by three laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona.

The results indicated a date between 1260 and 1390, suggesting a medieval origin.

Newspapers declared the case closed, yet the conclusion left room for debate.

The sampled corner had been heavily handled and repaired, particularly after a fire in the 16th century.

Textile experts argued that the threads might not represent the entire cloth and could skew the results.

While some defended the laboratories’ procedures, others pointed out that heterogeneous repairs could influence carbon dating subtly but significantly.

Alternative methods, such as X-ray scattering to study cellulose structure, occasionally indicated older ages, though these approaches carry large uncertainties.

Even pollen analysis and textile pattern studies hint at an origin consistent with the eastern Mediterranean, though none provide absolute proof.

The heart of the controversy lies in access and sampling.

The Shroud is a heavily guarded relic, limiting the areas that can be tested.

A small sample, no matter how meticulously analyzed, may fail to represent the whole artifact.

Any scientific claim is therefore tentative, contingent on location and method.

If the 1988 date is accurate, the Shroud would be a remarkable medieval creation, still unexplainable by known artistic techniques.

If the date is flawed, the question of its origin reopens, encompassing the early centuries of the Common Era.

Either way, the mystery persists, demanding careful study.

Into this landscape enters artificial intelligence.

While AI cannot determine the age of linen, it offers new ways to interrogate the image itself.

By analyzing high-resolution and multispectral photographs, including ultraviolet and infrared captures, AI systems can detect patterns invisible to the human eye.

Techniques such as principal component analysis, convolutional networks, and frequency filtering reveal repeating geometrical arrangements and faint symmetries that persist across the image.

These patterns do not resemble brushstrokes or toolmarks; instead, they appear as a kind of structured order, suggesting that the image may encode spatial information.

Researchers have long tested whether the image could have formed through direct contact with a body.

Simulations of draped cloth over a model body indicated distortions inconsistent with the relatively undistorted proportions on the Shroud.

The fit improved when cloth was imagined over a shallow relief rather than a full volume, implying that simple contact cannot fully explain the image.

AI analysis confirmed that darker regions correspond to closer points, while lighter areas indicate greater distance, producing a gradient that remains consistent across the image.

Such a correlation is difficult to achieve by hand and does not align with known medieval techniques.

Furthermore, microscopic studies show that the discoloration penetrates only the outer crowns of the fibers to a depth of mere microns, without seeping into the core, and edges are soft, not sharp.

Laser experiments and chemical treatments have failed to reproduce this effect reliably.

AI also identified subtle, repeating geometries on the face, chest, and even blurred hands, independent of stains or weave artifacts.

These patterns persisted across decades of images taken with different cameras and filters.

Neutral computational methods ruled out bias introduced by human expectations, confirming that the structure was intrinsic to the cloth.

Bloodlike stains appeared to exist independently of the geometrical order, suggesting that the image and stains may have been produced by separate processes.

Scientists have proposed various physical and chemical explanations.

The superficial image might have formed through a rapid energy burst interacting with a thin carbohydrate layer on the fibers.

Experiments with ultraviolet light, heat, and corona discharge show partial effects but fail to satisfy all constraints: superficiality, smooth edges, distance gradients, and stability over centuries.

Some have speculated about unknown plasma events or electrostatic phenomena, but no theory fully accounts for the observations.

Others have suggested a lost medieval technique, perhaps proto-photographic in nature, but the absence of pigment, binders, or deep penetration makes this unlikely.

Information theory offers a new lens.

The Shroud’s image behaves like a signal, with its geometrical structures akin to encoded data.

AI can analyze its robustness and explore whether simple rules govern its formation.

The cloth may contain information beyond mere visual representation, a record of processes not yet understood.

What emerges is a shift in perspective.

The debate should move from questions of origin or authenticity to questions of mechanism: how did the image form, what laws govern its structure, and which physical or chemical processes could account for the superficial, ordered discoloration? This approach encourages interdisciplinary study: physics students can explore energy transfer, chemists can investigate carbohydrate reactions, engineers can design gentle experimental setups, and custodians can weigh the benefits of minimal, non-destructive sampling.

The Shroud of Turin resists classification.

It straddles the line between artifact and phenomenon, between artistic creation and physical process.

This ambiguity is both a challenge and an opportunity.

Researchers are encouraged to measure before labeling, to test hypotheses rigorously, and to publish negative results as diligently as positive ones.

The Shroud teaches patience, humility, and careful inquiry, showing that some mysteries may remain partially unsolved for decades.

Its survival through centuries of handling, fire, and environmental stress underscores its resilience and the importance of cautious study.

The deeper implication is unsettling yet compelling: if the image is not accidental, it may reflect an unknown natural or artificial process, or even an intentional act of creation whose methods have been lost.

Each scenario challenges conventional categories.

If a natural phenomenon produced the image, science may eventually uncover a new physical or chemical law.

If it was human-created, it represents a technological sophistication unknown in medieval Europe.

If it defies both explanation, the Shroud remains a singular witness to a moment beyond current comprehension.

AI has not solved the Shroud, nor does it claim to.

Its contribution lies in illuminating the hidden order and suggesting where further experiments may be most revealing.

By mapping geometry, intensity gradients, and weave effects, AI helps prioritize future studies without presuming conclusions.

It functions not as an oracle but as a guide, offering new perspectives on an ancient artifact.

Ultimately, the Shroud of Turin exemplifies a rare intersection of faith, science, and technology.

It has prompted centuries of theological debate, scientific investigation, and now computational analysis, all while resisting definitive explanation.

The cloth’s image, with its shallow penetration, encoded spatial information, and repeating geometries, remains a challenge: neither proof of divinity nor forgery, but evidence of a process or phenomenon not yet fully understood.

This invites generations of researchers to explore, measure, and hypothesize without the pressure to provide absolute closure.

In the end, the Shroud’s power lies in its questions rather than its answers.

It asks how order can arise without conventional tools, how a simple fabric can record complex information, and how a mystery can endure while resisting easy resolution.

AI has revealed that beneath the surface of centuries-old linen, subtle patterns persist—patterns that obey laws yet to be named.

These discoveries do not diminish the relic; they enhance it, offering a new frontier where science, technology, and human curiosity converge.

Whether the cloth is unique or part of a wider class of artifacts, whether natural laws or lost techniques produced it, the Shroud continues to challenge assumptions, inspire wonder, and demand careful, patient inquiry.

The Shroud of Turin, once a symbol of devotion and doubt, is now also a testament to the power of observation, computation, and open-ended investigation.

Its legacy is not confined to the past—it shapes the way science approaches uncertainty, the way technology interrogates data, and the way humanity balances faith and evidence.

In its silent fibers, the Shroud continues to whisper mysteries that may one day be unraveled—or that may remain forever just beyond reach, inviting curiosity, discipline, and awe in equal measure.

News

Muslims Stormed a Church to Burn the Eucharist Then THIS HAPPENED…

I led seven men into a Catholic church to burn what Christians called the body of Christ, convinced we were…

Muslims Stormed a Church to Steal the Communion Unaware What Jesus Had Planned…

Four Muslim men walked into a church to prove Christianity was fake by taking communion and feeling nothing. What happened…

Arab Royal Mocked Jesus Publicly in Dubai, Then Dropped to One Knee in Shock vd

On December 15th, 2018, I stood before 5,000 Muslims in Dubai and spent 45 minutes mocking Jesus Christ, calling him…

A Catholic Mass Was Interrupted When Muslim Men Stole Chalice—What Happened Next Shocked Everyone

On December 8th, 2019, I walked into a Catholic church with three other Muslim men and grabbed the sacred cup…

R Kelly Thrown In “The Hole” After Alleged Prison Assassination 😳 New Trial Filing GOES LEFT

Our Kelly’s legal team just dropped bombshell allegations claiming the singer is not just serving time. He’s literally fighting for…

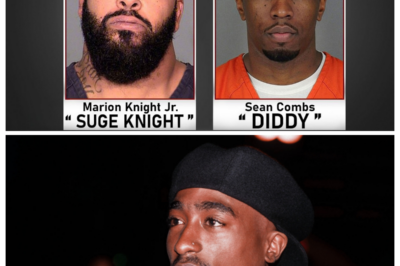

Diddy & Suge Knight CHARGED For Tupac’s Death

Nearly three decades after the death of Tupac Shakur, renewed debates continue to surface regarding who was ultimately responsible and…

End of content

No more pages to load