For centuries, a single piece of linen has stood at the center of one of humanity’s most enduring mysteries.

Known as the Shroud of Turin, this ancient cloth has defied simple explanation, hovering between faith and science, devotion and doubt.

To believers, it bears silent witness to the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth.

To skeptics, it is an extraordinary but human-made artifact.

Yet with every attempt to resolve the debate, the Shroud seems to offer not answers, but deeper questions.

In recent years, the arrival of artificial intelligence has added an unexpected new layer to this story, revealing patterns and structures that challenge everything previously assumed about the cloth and the image it bears.

The Shroud itself is deceptively simple in appearance.

It is a long strip of linen, woven in a herringbone twill, measuring roughly fourteen feet in length and just over three feet in width.

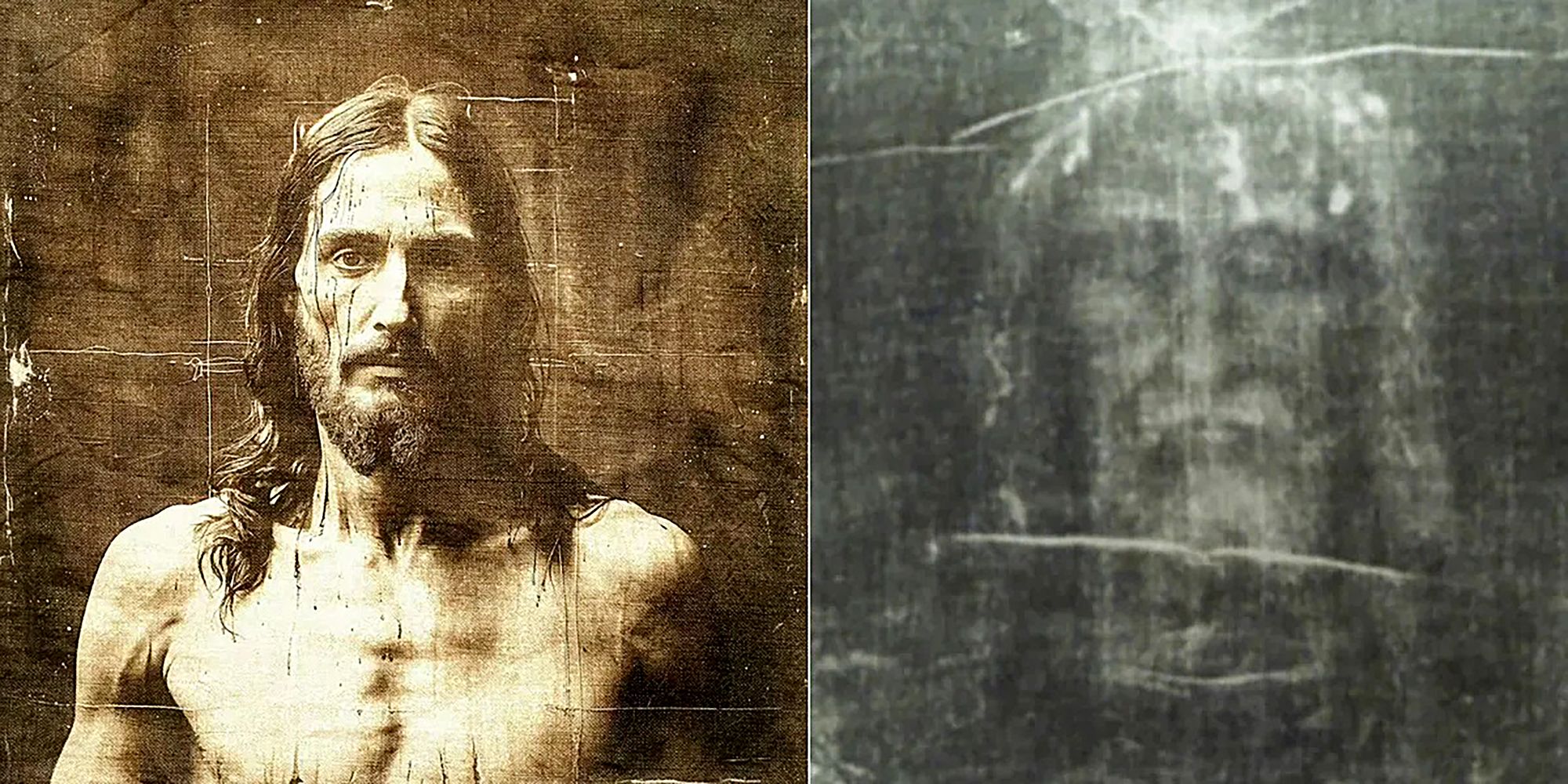

On its surface appears the faint, ghostlike image of a man seen from both front and back, as if a body had once been laid upon it and then vanished.

The image is not vivid or painted; it is subtle, almost shy, emerging more clearly only when studied closely or photographed.

The figure shows wounds that align with Roman crucifixion practices: marks at the wrists rather than the palms, a wound in the side consistent with a spear thrust, bloodlike stains around the head resembling punctures from a crown of thorns, and abrasions across the back suggestive of scourging.

The face is serene yet lifeless, eyes closed, beard parted, hair falling in soft strands that seem to hover above the fabric rather than sink into it.

Historical records place the Shroud’s first undisputed public appearance in fourteenth-century France, where it quickly became both an object of pilgrimage and controversy.

From there, it passed through noble hands, survived fires and repairs, and eventually came to rest in Turin, Italy, under the protection of the House of Savoy.

Today it is preserved in a climate-controlled case inside the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, rarely displayed and carefully guarded.

Despite its protected status, the Shroud has endured centuries of scrutiny, with each generation bringing new tools to interrogate its origins.

A pivotal moment came in 1898, when amateur photographer Secondo Pia captured the first photographic images of the cloth.

When he developed his negatives, he was stunned to find that the negative image revealed a far clearer, more lifelike face than the cloth itself.

The Shroud’s image behaved like a photographic negative centuries before photography existed.

This discovery did not prove authenticity, but it transformed the Shroud from a devotional object into a scientific problem.

From that moment on, laboratories joined chapels, and microscopes joined prayers.

Throughout the twentieth century, scientists examined the Shroud using the best methods available.

Chemical analyses searched for pigments and binders but found none.

Microscopic studies revealed that the image resides only on the outermost fibrils of the linen threads, penetrating mere microns into the surface and leaving the inner fibers unchanged.

The discoloration appeared to be a result of oxidation or dehydration rather than paint, dye, or scorch marks.

Forensic studies noted that the bloodlike stains appeared to be real blood, applied before the image formed, as the image did not appear beneath the stains.

Textile experts studied the weave, comparing it to ancient looms from the Middle East.

Pollen analysts identified grains from plants native to the Mediterranean and Near East.

Each finding added complexity rather than clarity, reinforcing the sense that the Shroud refused to behave like an ordinary artifact.

The most dramatic scientific intervention came in 1988, when a small sample of the cloth was subjected to radiocarbon dating by three independent laboratories.

The results dated the sample to the medieval period, roughly between 1260 and 1390.

For many, this seemed to close the case.

Headlines declared the Shroud a medieval creation, and the mystery appeared solved.

Yet the simplicity of that conclusion soon unraveled.

Critics pointed out that the sample was taken from a single corner of the cloth, an area that had been heavily handled and possibly repaired after a documented fire.

Some researchers argued that the fibers from that region showed signs of later weaving or contamination, potentially skewing the results.

While defenders of the test maintained its validity, the debate exposed a deeper issue: when access to an artifact is limited, a small sample can carry enormous interpretive weight.

As the dating controversy simmered, attention returned to the image itself.

One of its most intriguing properties is its apparent three-dimensionality.

When image intensity is converted into height data, the result resembles a coherent relief, as if the darkness of the image corresponds to the distance between the cloth and a human body.

This is highly unusual.

Paintings, photographs, and contact impressions do not naturally encode spatial depth in this way.

Attempts to replicate the effect using heat, chemicals, or artistic techniques have produced approximations, but none have matched the Shroud’s combination of superficiality, uniformity, and spatial mapping.

It is within this unresolved landscape that artificial intelligence entered the debate.

Unlike human observers, AI systems do not carry expectations shaped by belief or skepticism.

They excel at detecting subtle patterns across massive datasets, patterns that may be invisible to the naked eye.

When high-resolution, multispectral images of the Shroud were analyzed using advanced computational methods, researchers expected confirmation of known features.

Instead, they encountered something stranger.

Beneath the familiar image of face and body, algorithms detected recurring geometric relationships and intensity patterns that persisted across different wavelengths of light and different photographic sources.

These patterns did not resemble brushstrokes, stamps, or fabric distortions.

They appeared consistent, rule-bound, and independent of the linen’s weave.

Even more unsettling, the geometry seemed unaffected by the bloodstains, suggesting that the image and the stains were formed by separate processes.

In other words, whatever created the body image did not disturb the blood, and whatever deposited the blood did not disrupt the underlying pattern.

This separation challenges both artistic and accidental explanations.

To guard against the risk of seeing meaning where none exists, researchers applied neutral statistical techniques designed to minimize bias.

Principal component analysis stripped away obvious visual features, leaving only the most persistent signals.

The patterns remained.

Control tests on other ancient linens, as well as on fabrics treated with heat or chemicals, failed to produce comparable results.

The conclusion was cautious but profound: the Shroud’s image is not merely rare; it behaves differently from known images.

Importantly, AI did not solve the mystery.

It did not declare the Shroud authentic or fraudulent.

It did not assign a date or identify a cause.

Instead, it reframed the problem.

The image appears less like a conventional artifact and more like the record of a physical phenomenon—something governed by laws rather than by tools.

That distinction matters.

Artifacts imply craftsmanship and intention.

Phenomena imply processes that can, in principle, be described by physics and chemistry, even if they are not yet understood.

This reframing has unsettled both skeptics and believers.

For skeptics, it complicates the narrative of medieval artistry, as no known technique from any era convincingly explains the Shroud’s properties.

For believers, it cautions against premature claims of miracle, reminding us that unexplained does not mean unexplainable.

Within the scientific community, reactions have been measured.

Some describe the image as a “decaying signal,” others as “spatial information preserved in linen.

” These phrases reflect uncertainty rather than conclusion.

What makes the Shroud particularly challenging is that it resists classification.

It is not easily grouped with other relics, artworks, or natural impressions.

No confirmed “cousins” exist—no other fabrics bearing comparable superficial images with similar spatial encoding.

This uniqueness raises the stakes.

If similar objects were found, the mystery might become mundane.

If none are found, the Shroud stands alone, demanding either an unknown process or an extraordinary convergence of known ones.

At its core, the Shroud of Turin now poses a better question than it ever has before.

Not “Who does it depict?” or “When was it made?” but “What process could produce this image?” That question invites collaboration rather than conflict.

It calls on physicists to explore gentle energy interactions with cellulose, chemists to study surface-level oxidation, engineers to model non-contact imaging mechanisms, and custodians to consider whether new, non-destructive testing might be possible.

The true significance of AI’s contribution is not that it has uncovered a hidden code or solved a sacred riddle.

It is that it has confirmed the Shroud’s strangeness with new rigor.

The cloth continues to defy easy answers, but it now does so with quantified anomalies rather than vague impressions.

In doing so, it bridges a gap between faith and science, forcing each to slow down, listen, and respect the limits of certainty.

The Shroud of Turin remains what it has always been: a mirror reflecting human hopes, doubts, and curiosity.

Artificial intelligence has not ended the debate.

It has sharpened it, transforming wonder into structured inquiry.

Whether the Shroud ultimately yields to explanation or remains an outlier beyond our current understanding, its value endures.

It reminds us that some objects are not puzzles to be solved quickly, but invitations to think more deeply about how we know what we know—and how much we have yet to learn.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load