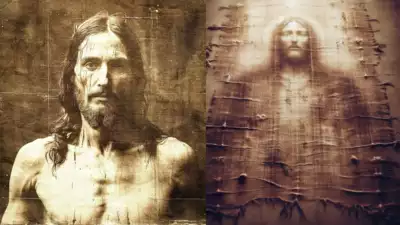

For centuries, a single linen cloth has unsettled scholars, believers, and skeptics alike.

Known as the Shroud of Turin, it bears the faint image of a crucified man and has endured as one of the most debated relics in human history.

Some have dismissed it as a medieval fabrication, others have revered it as sacred testimony, and still others have treated it as an unsolved scientific puzzle.

In recent years, the debate has entered an unexpected new phase as artificial intelligence was applied to the study of the cloth.

What emerged was neither a clear verdict nor a simple explanation, but something far more unsettling: hidden structure, repeating geometry, and mathematical order embedded within ancient linen in ways that defy conventional understanding.

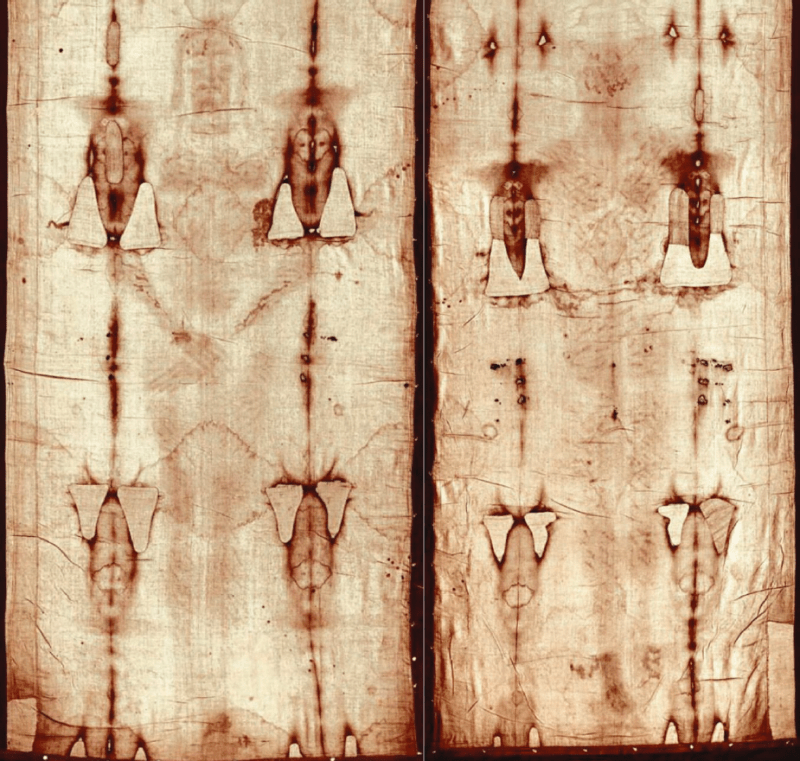

The Shroud of Turin is a long strip of woven flax measuring roughly fourteen feet in length and a little over three feet in width.

The fabric is made in a herringbone twill pattern that reflects light subtly, giving the surface a shifting appearance.

Upon this surface appears the front and back image of a man, aligned head to head, as if a body had once been laid upon the cloth and then removed without disturbing its folds.

The image is extremely faint, almost invisible at first glance, yet unmistakable once perceived.

It depicts wounds consistent with Roman crucifixion, including marks at the wrists and feet, a wound on the side resembling a spear thrust, and abrasions on the scalp suggestive of a crown of thorns.

The face appears calm, eyes closed, with a parted beard and long hair that seems to hover above the weave.

The earliest confirmed historical records of the shroud place it in France during the thirteenth century, where it was publicly displayed and quickly became an object of pilgrimage and controversy.

Critics accused church authorities of promoting a forgery, while devotees defended its authenticity.

Over time, the cloth passed through various hands until it came under the care of the House of Savoy and was eventually transferred to Turin in sixteen seventy eight.

Since then, it has been preserved in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, protected by modern conservation methods yet still exposed to fire, smoke, and environmental stress across the centuries.

A pivotal moment in the modern history of the shroud occurred in eighteen ninety eight, when an Italian lawyer and amateur photographer, Secondo Pia, took the first photographic images of the cloth.

When he developed the photographic plates, he discovered that the negative revealed a strikingly detailed positive image of a human face and body.

Features that were barely visible to the naked eye emerged with clarity on the negative, suggesting that the image on the cloth itself functioned like a photographic negative long before photography existed.

This discovery transformed the shroud from a devotional object into a scientific enigma.

Throughout the twentieth century, the shroud underwent extensive scientific examination.

Chemists analyzed fibers, forensic experts studied the wound patterns, and textile historians compared the weave to known ancient fabrics.

One of the most puzzling findings was that the image did not appear to be painted, dyed, or stained in any conventional sense.

There were no brush marks, no pigment particles, and no evidence that color penetrated deeply into the fibers.

Instead, the discoloration was confined to the outermost fibrils of the threads, affecting only a microscopic surface layer.

This superficiality proved extremely difficult to replicate using known techniques.

Another intriguing characteristic emerged when researchers analyzed the image intensity.

When brightness levels were converted into three dimensional data, the image appeared to contain information related to distance between the cloth and a body surface.

Darker areas corresponded to regions that would have been closer to a body, while lighter areas suggested greater separation.

This kind of spatial encoding is highly unusual for an image that lacks pigment or deliberate shading.

In nineteen eighty eight, a major effort was made to resolve the question of the shroud age through radiocarbon dating.

Samples taken from one corner of the cloth were analyzed independently by laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona.

All three returned dates placing the fabric between the years twelve sixty and thirteen ninety.

For many observers, this result seemed decisive, firmly situating the shroud in the medieval period.

However, the debate did not end there.

Critics argued that the sampled corner may have contained later repair threads or contamination from centuries of handling and exposure to smoke.

Questions were raised about whether a single sample could represent the entire cloth.

Subsequent studies explored alternative dating methods, including analysis of cellulose degradation and mechanical properties of the linen.

Some results suggested an older origin, though uncertainties remained high.

The lack of permission for extensive new sampling has meant that the dating controversy remains unresolved, with each side pointing to methodological limitations in the other.

As the twenty first century progressed, a new analytical approach became possible.

High resolution digital images of the shroud were processed using artificial intelligence systems designed to detect patterns beyond human perception.

These systems did not bring beliefs or assumptions.

They simply analyzed data.

When the shroud images were examined using advanced statistical and computational techniques, researchers observed consistent geometric relationships within the image that did not align with the fabric weave or known artistic methods.

The AI analysis revealed repeating ratios and symmetrical structures embedded across the face and torso.

These patterns persisted across different wavelengths of light, including visible and ultraviolet, and remained even when obvious noise and artifacts were removed.

Importantly, these structures did not correspond to areas of blood staining, suggesting that the image and the blood marks were formed by different processes.

This separation reinforced earlier observations that the image was not created by liquid transfer or direct contact alone.

Attempts were made to reproduce similar effects using heat, chemical reactions, and electrical discharge on linen.

While some methods produced partial similarities, none replicated all the characteristics simultaneously.

Most notably, they failed to achieve the same level of superficial discoloration combined with consistent distance mapping.

The shroud image continued to stand apart from experimental analogues.

The emergence of AI did not solve the mystery, but it reframed it.

Instead of asking who created the image or when, researchers increasingly focused on how such an image could form at all.

The cloth appeared to record an event rather than depict a scene.

Its behavior resembled that of a physical phenomenon governed by rules rather than an artifact shaped by tools.

Reactions within the scientific community were cautious.

Some welcomed the findings as evidence that the shroud deserved further study, while others warned against overinterpretation.

Theological responses varied as well, with some viewing the results as supportive of belief and others urging restraint.

The Catholic Church maintained its long standing position of neither endorsing nor rejecting the shroud authenticity, emphasizing its value as an object of contemplation rather than proof.

What made the AI findings particularly unsettling was their neutrality.

The technology neither affirmed miracle nor confirmed forgery.

It simply demonstrated that the image contained an unexpected level of order.

This order did not conform neatly to existing categories, challenging researchers to expand their frameworks rather than force conclusions.

The shroud now occupies a unique position at the intersection of science, history, and philosophy.

It is simultaneously a relic, a dataset, and an unresolved question.

Artificial intelligence has added a new layer to its story, not by providing answers, but by revealing complexity where simplicity was expected.

The cloth continues to resist definitive explanation, inviting careful measurement, patient inquiry, and intellectual humility.

In the end, the most unsettling possibility is not that the shroud proves too much, but that it proves nothing while refusing to be ordinary.

It challenges assumptions about image formation, material science, and the limits of analysis.

Whether it is ultimately explained as a rare natural process, a lost technological achievement, or something not yet understood, the Shroud of Turin remains a reminder that some objects endure not because they resolve debates, but because they deepen them.

News

15 Weird Facts About What Happens When a Pope Dies

When the spiritual leader of more than one billion Catholics dies, a complex sequence of rituals begins almost immediately. These…

Michael Jackson’s Mystery Is Finally Solved in 2025—Leaving Everyone Speechless For years, unanswered questions surrounded Michael Jackson’s final days, private life, and legacy. Now, developments emerging in 2025 are forcing fans and experts alike to reconsider what they thought they knew.

Reexamined records, new testimony, and long-ignored details are coming together in a way no one expected—quietly reshaping the narrative.

Is this true closure, or just another layer of a deeper mystery? Click the article link in the comments to discover why the world is stunned.

In 2025 a wave of documentaries court filings and reexamined interviews pushed the death of Michael Jackson back into the…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Secret Garage Search Reveals Tupac Shakur Was Preparing an Escape Before His Death Nearly twenty seven years after the death…

C0ps JUST Disc0vered Tupac’s Hidden St0rage L0cker — What Was Inside Left Them Stunned

Newly Disc0vered St0rage L0cker Adds Expl0sive Evidence t0 the Renewed Tupac Shakur Murder Investigati0n Nearly three decades after the k*lling…

28 Years Later, Tupacs Mystery Is Finally S0lved in 2025, And It’s Bad

The Tupac Shakur Case Re0pened: New Evidence, Old C0nfessi0ns, and a Darker Truth Emerging After 28 Years Nearly twenty eight…

Shocking New Footage Of Tupac After His Murder Stunned Everyone Years Later

Renewed Investigation and Viral Footage Reignite the Global Mystery of Tupac Shakur Death Nearly three decades after the fatal shooting…

End of content

No more pages to load