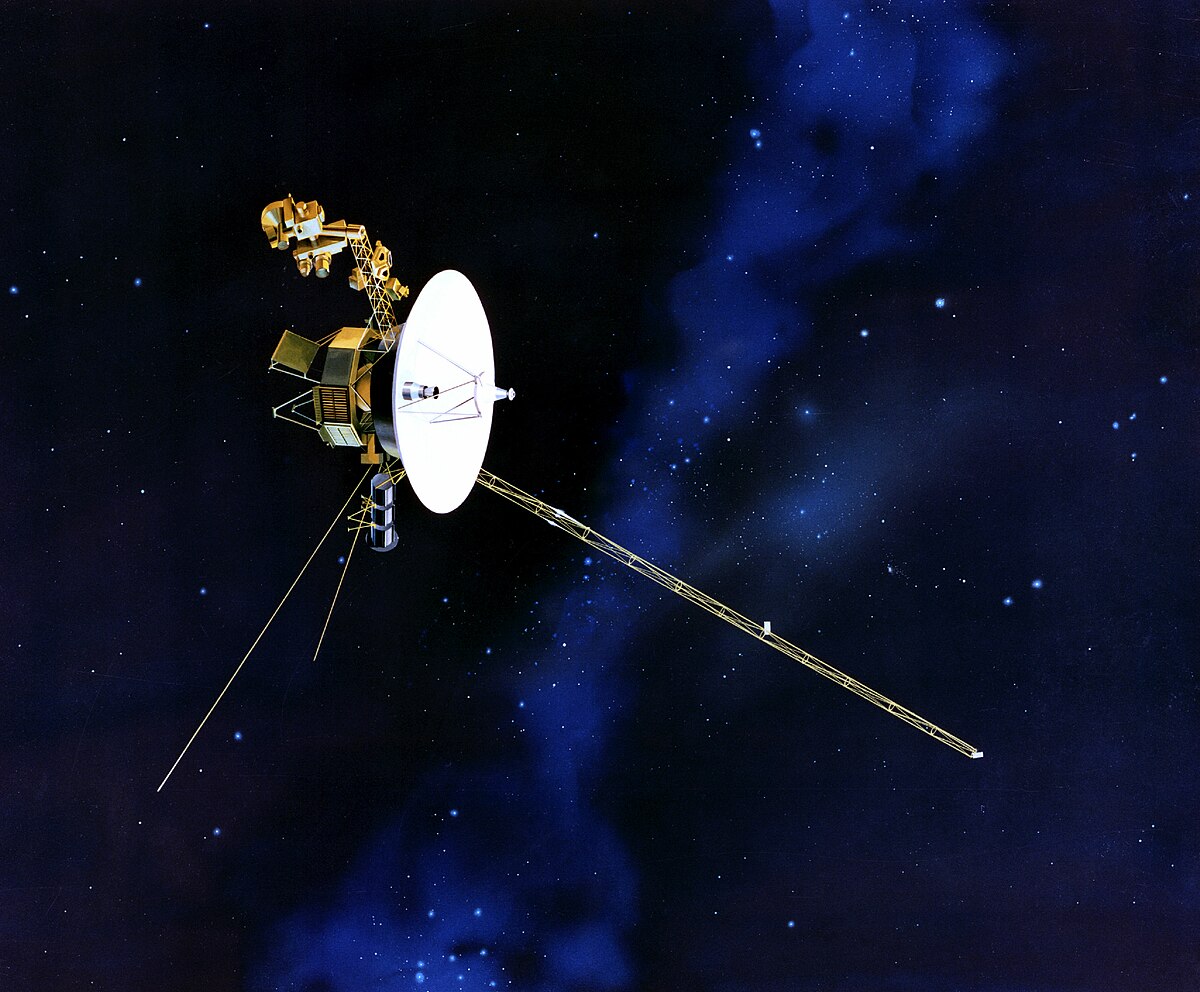

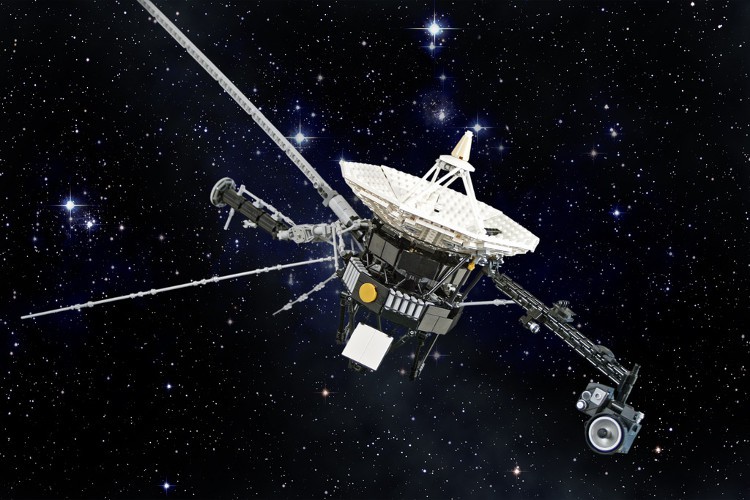

Voyager 1 and 2: Decades of Discovery at the Edge of the Solar System and Beyond

For nearly five decades, humanity’s eyes on the outer solar system—Voyager 1 and Voyager 2—have quietly transmitted invaluable scientific data from the distant reaches of space.

Launched in 1977, these twin spacecraft were tasked with exploring the outer planets, their moons, rings, and magnetic environments, before venturing into the uncharted expanse of interstellar space.

Over the years, the Voyagers have not only expanded our understanding of the solar system but also challenged long-standing scientific assumptions, revealing anomalies and phenomena that continue to intrigue scientists today.

Voyager 2’s encounter with Uranus in January 1986 remains one of the most remarkable chapters in the mission’s history.

The spacecraft passed within 81,500 kilometers of the planet’s cloud tops, providing humanity’s only close-up observations of this distant world.

Uranus, rotating on its side with an extreme axial tilt, defied expectations at every turn.

Its magnetic field was dramatically misaligned, forming a twisted geometry and extending into a helical tail that reached millions of kilometers into space.

Voyager 2 captured the existence of eleven previously unknown moons, a complex ring system unlike that of Jupiter or Saturn, and detailed images of icy satellites like Miranda, whose enormous canyons hinted at a turbulent past.

The spacecraft also revealed a dynamic atmosphere.

Concentric cloud bands swirled near the South Pole, while ultraviolet emissions radiated from the upper atmosphere in patterns previously unobserved.

Remarkably, temperatures remained uniform across the planet, despite decades-long seasons and extreme sunlight exposure at the poles.

Deep within the clouds, Voyager 2 detected lightning discharges of extraordinary intensity, brief but powerful bursts of energy rivaling terrestrial lightning.

Yet, Uranus presented its most perplexing mystery in the form of an unexpectedly intense electron radiation belt.

Conventional models had predicted Uranus would have relatively weak radiation, but Voyager 2 recorded electron energies that rivaled much larger planets.

For decades, scientists could not explain how these belts were maintained, as prevailing theories suggested that high-frequency electromagnetic waves near Uranus would scatter electrons and diminish radiation intensity.

It was only with decades of subsequent research that the anomaly found context.

Modern analyses suggest that Voyager 2 encountered Uranus during an intense space weather event, specifically a co-rotating interaction region, where fast-moving solar wind collided with slower streams, compressing plasma and magnetic fields.

Such events, previously studied near Earth, are known to energize radiation belts rather than disperse them.

Comparing Voyager 2’s Uranus data to a 2019 solar wind event near Earth revealed consistent signatures, suggesting that the intense radiation was a transient phenomenon rather than a permanent feature of the planet.

In this light, Voyager 2’s final Uranian readings captured a rare cosmic event, reshaping long-standing assumptions about planetary radiation belts.

After completing its planetary encounters, Voyager 2 embarked on an extended mission to study the heliosphere—the outer boundary of the Sun’s influence—and eventually interstellar space.

Voyager 1, which had already passed the outer planets, followed a similar path.

By the early 2010s, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to enter interstellar space at a distance of 121 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, followed by Voyager 2 in 2018.

These journeys provided unprecedented measurements of plasma density, magnetic fields, and cosmic ray behavior in regions where the Sun’s influence wanes and interstellar conditions dominate.

Throughout their interstellar mission, the Voyagers continued to encounter surprises.

In October 2020, both spacecraft recorded an unexpected rise in particle density beyond the heliosphere, revealing large-scale structures within the local interstellar medium that had not been previously observed.

These findings demonstrated that even after decades of travel, the Voyagers continued to uncover novel phenomena that challenge our understanding of space beyond the solar system.

The Voyagers’ longevity is a testament to the ingenuity of their engineering and the skill of the teams managing them.

Operating on computer systems designed in the 1970s, each spacecraft contains three primary computers: one monitors spacecraft health, another manages orientation and thruster firing to maintain antenna alignment, and a third stores and transmits scientific data.

Combined, these computers contain just 70 kilobytes of memory, roughly the size of a single modern photograph.

Despite this, their design has proved remarkably resilient, surviving decades of radiation, extreme temperatures, and isolation.

Updates and interventions—often transmitted across billions of miles at rates as low as 16 bits per second—have been carefully executed in assembly and Fortran code, converted into machine instructions to maintain functionality.

Maintaining communications with spacecraft so distant presents unique challenges.

Signals take nearly a full day to travel one way, requiring extreme precision in command timing and execution.

As the spacecraft age, engineers have been forced to implement careful management strategies, prioritizing essential instruments and turning off non-critical systems to conserve power.

Voyager 2, for example, systematically shut down instruments such as the plasma science subsystem in 1991, the ultraviolet spectrometer in 1998, and the digital tape recorder in 2007.

By 2025, only a handful of critical instruments remain operational, preserving the ability to gather high-value data while stretching the limited power supply of its radioisotope thermoelectric generator.

Thruster management has also become increasingly critical.

Hydrazine buildup in the thrusters used to orient the spacecraft poses the risk of clogging, which could prevent the high-gain antennas from remaining accurately pointed toward Earth.

To mitigate this, NASA developed software updates to slow thruster degradation and successfully reactivated backup thrusters, ensuring continued orientation control.

Similar interventions have maintained Voyager 1’s ability to transmit data and respond to commands despite decades of wear.

Yet even with careful maintenance, anomalies continue to arise.

Voyager 1 has recently exhibited unexpected behavior, including transmissions that shifted from structured scientific data to continuous binary streams that could not be decoded.

The spacecraft adjusted its orientation independently, suggesting internal reactions that remain unexplained.

Voyager 2 has experienced its own communication challenges, including misaligned antennas and transient telemetry disruptions.

Engineers have managed these events through creative software solutions, re-routing commands, and restoring essential functions from intact memory banks.

Despite these hurdles, both spacecraft continue to provide invaluable scientific observations.

Voyager 1 now lies approximately 15.

1 billion miles from Earth, transmitting measurements of particles, magnetic fields, and cosmic radiation from the boundary between the solar system and interstellar space.

Voyager 2, slightly closer, continues complementary measurements, providing context to Voyager 1’s findings.

Together, the probes offer the only direct observations humanity has of interstellar space, making them essential tools for understanding the Sun’s interaction with the galaxy.

Looking forward, the Voyagers’ operational lifetimes are finite.

By around 2030, Voyager 2 is expected to lose all power to its instruments, and by 2036, both spacecraft will drift beyond the range of the Deep Space Network.

After this, they will continue their journey silently, orbiting the galaxy for tens of thousands of years.

Voyager 1 will eventually traverse the theorized Oort Cloud, passing within 1.66 light-years of a star in approximately 40,000 years and continuing indefinitely into the Milky Way.

These distant wanderings underscore the enduring legacy of the Voyager missions: even as they fall silent, they will continue to carry humanity’s message and our scientific curiosity into the cosmos.

The achievements of the Voyager spacecraft are as much a testament to human ingenuity as to the mysteries of the universe.

The planetary encounters revealed complex, dynamic worlds; the heliospheric missions redefined our understanding of the Sun’s outer boundary; and the interstellar observations continue to challenge long-held assumptions about cosmic environments.

Each anomaly, each unexpected reading, serves as a reminder that space remains a frontier of discovery, and that even a tiny, aging spacecraft can illuminate vast and uncharted regions of our universe.

As Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 approach the limits of their operational capacity, they exemplify the intersection of technology, science, and persistence.

Engineers and scientists at NASA have managed these missions with unparalleled precision, adapting decades-old technology to respond to conditions no one could have anticipated in the 1970s.

Through careful power management, thruster operation, and software updates, they have extended the Voyagers’ capabilities far beyond their original design, ensuring that even as the probes grow older, they continue to return data that pushes the boundaries of human knowledge.

The legacy of the Voyagers is not only scientific but symbolic.

They demonstrate humanity’s ability to reach beyond the confines of our planet, to touch the outer solar system, and to enter interstellar space.

They remind us that exploration is a long-term endeavor, often spanning generations, and that the pursuit of knowledge requires patience, ingenuity, and the willingness to adapt to unforeseen challenges.

From the first glimpses of Uranus’s tilted magnetic field to the detection of interstellar particles billions of miles from the Sun, the Voyagers have consistently provided insight into realms previously invisible to human observation.

In conclusion, the Voyager missions have transformed our understanding of the solar system and interstellar space.

They have revealed distant planets in unprecedented detail, captured rare space weather events, and provided the first direct measurements of the environment beyond the Sun’s influence.

Even as power wanes and instruments are gradually retired, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 continue to operate as the farthest human-made objects from Earth, transmitting data that will inform science for decades to come.

Their journey serves as a testament to human curiosity, technical skill, and the enduring quest to explore the unknown.

For nearly half a century, the Voyagers have bridged the gap between the familiar and the cosmic, and their legacy will continue to inspire generations of explorers, scientists, and dreamers.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load