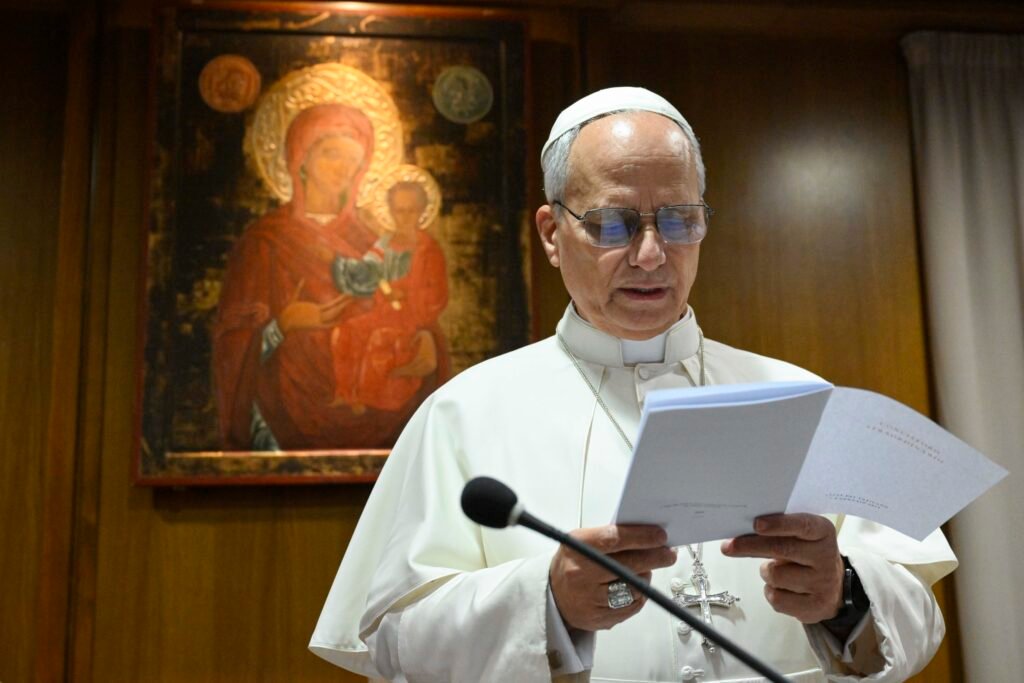

Limestone dust clung to the white cassock of Pope Leo the Fourteenth as he emerged from beneath the marble foundations of Saint Peter’s Basilica, an image that would soon circle the globe.

At the time, however, the pontiff was not thinking about photographs, symbolism, or history.

His focus was fixed on truth, on the weight of what had just been uncovered twenty meters below the heart of Christianity.

The discovery began before dawn on November twentieth, when an urgent call reached the Vatican Secretary of State.

Restoration crews working to stabilize the Constantinian foundations beneath the basilica had encountered an anomaly during routine reinforcement.

Ground penetrating radar had revealed a void where none should have existed.

As engineers carefully broke through late Roman masonry, they uncovered a sealed chamber whose construction predated Constantine by centuries.

The Vatican’s chief engineer, Marco Benedetti, immediately understood the gravity of the situation.

The stonework was unmistakably first century in character, carefully sealed and deliberately hidden.

Recognizing that such a discovery exceeded technical authority, he contacted the Secretary of State, who in turn placed a call to the pope’s private residence.

Pope Leo the Fourteenth answered without hesitation.

He had already been awake, immersed in early Christian writings, a habit formed during decades of scholarly and pastoral work.

After receiving a brief but urgent explanation, he made a swift decision.

He would see the chamber himself.

No press, no public announcement, and no delay.

Within minutes, the pope descended beneath the basilica accompanied only by the Secretary of State, the chief engineer, and Father Joseph Lombardi, the Vatican’s leading archaeologist.

They passed through dim corridors lined with ancient tombs, spaces untouched for more than a millennium.

Electric lights cast long shadows on stone that had witnessed the earliest centuries of Christian history.

At the edge of the excavation, a temporary wooden barrier marked the breach.

Beyond it lay darkness and cool air scented with limestone and herbs.

When Father Lombardi directed his flashlight into the opening, the beam illuminated walls covered with ancient plaster, fragments of symbols, and faded markings unmistakably Christian in origin.

The chamber itself was modest in size, roughly four meters square, yet its significance was immense.

The walls bore crude images of fish, shepherds, raised hands, and early inscriptions scratched into plaster by untrained hands.

These were not decorative works.

They were acts of devotion carried out under threat of death.

One inscription drew immediate attention.

Its wording suggested a community gathering in secrecy at a time when association with the name of Christ meant execution.

Based on linguistic analysis and stylistic features, Father Lombardi estimated the inscription dated to within thirty years of the crucifixion.

The silence in the chamber was profound.

There was no sound from above, no echo of the vast basilica overhead, only the sense of a space preserved deliberately through centuries of concealment.

The pope examined the room carefully, noting what appeared to be the remains of a simple stone altar in one corner, likely designed to be dismantled quickly if Roman soldiers approached.

The implications were unmistakable.

This was not merely an ancient room.

It was evidence of continuous sacred use of the site dating back to the apostolic generation.

Christians had gathered here to worship while persecution raged above them, and later builders had chosen not to destroy or expose the chamber, but to seal it carefully and build over it.

The pope knelt briefly in the dust, not in ceremony, but in contemplation.

The first believers had prayed here without certainty, without safety, and without institutional support.

They had nothing but faith and one another.

After returning to the surface, the group convened in the papal apartments for an emergency meeting that extended well into the morning.

Present were senior officials responsible for doctrine, archaeology, engineering, and governance.

Photographs of the chamber circulated quietly across the table.

The discussion was intense.

Proper archaeological procedure required careful documentation, peer review, and years of analysis before any public statement.

Premature disclosure risked academic controversy and public misunderstanding.

Yet the pope remained resolute.

The decision was made to announce the discovery immediately.

Full investigation would proceed transparently, but concealment would not continue.

The chamber had been hidden long enough.

A brief statement was released by the Vatican press office the following morning.

It confirmed the discovery of a sealed chamber beneath Saint Peter’s Basilica containing evidence of early Christian worship.

Preliminary findings suggested a first century origin.

The pope had personally inspected the site.

Comprehensive archaeological study would begin at once.

The response was immediate and global.

News organizations redirected resources to Vatican City.

Scholars issued preliminary analyses.

Skeptics demanded evidence.

Believers saw confirmation of long held traditions.

Social media filled with debate and speculation.

One image, however, came to define the moment.

Taken informally by the chief engineer, it showed Pope Leo emerging from the excavation, his white clothing marked with limestone dust, his expression distant and contemplative.

Shared privately at first, the photograph spread rapidly online and was soon featured across international media.

Many saw in it a symbol of leadership willing to descend into uncertainty rather than remain above it.

Later that day, the pope released a brief recorded statement.

He spoke of discovering a place where early Christians had gathered in fear and hope, where they had prayed and shared bread when doing so risked death.

He emphasized that faith existed there long before marble, gold, or hierarchy.

The message was simple.

What sustained the first believers remained sufficient today.

Scholarly investigation intensified in the weeks that followed.

Carbon dating confirmed late first century materials.

Epigraphic analysis aligned with known early Christian inscriptions.

The chamber’s location directly beneath the traditional site of Peter’s martyrdom matched historical accounts preserved in ancient texts.

Debates arose over interpretation and context, as expected, but the core finding remained uncontested.

The chamber represented one of the earliest known Christian worship spaces, preserved beneath the most prominent church in Christendom.

Particular attention focused on the decision by fourth century builders to seal the chamber rather than incorporate or destroy it.

Evidence suggested deliberate preservation.

Constantine’s engineers had known what they found and chose silence over exposure, safeguarding the site for future generations without risking desecration.

The pope visited the chamber several more times in the following weeks, always without announcement.

He brought no advisers and allowed no photographs.

When asked about these visits, he said only that he listened.

Public access to the site became a subject of intense discussion.

Eventually, the Vatican confirmed that the chamber would be opened in the future under strict conservation protocols, but not before extensive preservation work.

Exposure to air had already begun to affect the fragile plaster.

Rushing public visitation would risk irreversible damage.

Some criticized the delay, but the pope addressed the matter directly.

The responsibility of discovery, he said, was protection before presentation.

The first believers had not created the space for future admiration, but for survival and worship.

That intent would be honored.

Beyond archaeology, the discovery reshaped internal church conversations.

It became a reference point in debates about authority, bureaucracy, and reform.

The chamber reminded leaders that Christianity began underground, illegal, and vulnerable.

There were no institutions, no privileges, and no guarantees.

The pope invoked the chamber often, not as an argument but as a reminder.

When critics demanded faster change, he pointed to the patience of those who risked everything.

When others resisted reform, he reminded them that the earliest church thrived without power.

By December, the initial shock had settled into reflection.

Universities launched research initiatives.

Seminaries adjusted curricula.

Parishes discussed the meaning of faith stripped of grandeur.

The chamber itself remained sealed, quiet beneath the basilica where masses continued above.

Tourists photographed marble and gold unaware of the fragile space below, where whispers once replaced hymns.

The image of the pope in dust-stained white endured.

It came to represent a moment when leadership chose proximity to origins over distance from discomfort.

Late one evening, the pope stood overlooking Rome, reflecting on the discovery.

He spoke quietly of the courage of those who had prayed in darkness without knowing whether their faith would survive.

They did not know the future, yet they were faithful.

The chamber beneath Saint Peter’s Basilica remained closed, but its message had emerged into the light.

Faith, at its beginning, was simple, fragile, and fearless.

After two thousand years, it had been found again, not in theory or tradition, but in stone, dust, and silence beneath the most magnificent church built in its name.

News

The Sinister Secrets of the Red Sea: Pharaoh’s Chariot Wheel Discovered!

The Sinister Secrets of the Red Sea: Pharaoh’s Chariot Wheel Discovered! In a stunning twist of fate, a team of…

The Dark Truth Behind the Challenger Disaster: What Happened to the Crew?

The Dark Truth Behind the Challenger Disaster: What Happened to the Crew? On a seemingly perfect January morning in 1986,…

The Mysterious Plane in Space: A Cosmic Enigma Unveiled

The Mysterious Plane in Space: A Cosmic Enigma Unveiled It began as just another day in orbit, a routine mission…

The Shocking Revelation from an Ancient Babylonian Tablet: What AI Discovered Will Leave You Speechless

The Shocking Revelation from an Ancient Babylonian Tablet: What AI Discovered Will Leave You Speechless Imagine a world where the…

The Mystery of MH370: A Signal from the Abyss

The Mystery of MH370: A Signal from the Abyss In the depths of the ocean, where light dares not tread,…

The Disturbing Warning: A 13-Year-Old’s Alarming Revelation About CERN

The Disturbing Warning: A 13-Year-Old’s Alarming Revelation About CERN In a world driven by science and reason, a 13-year-old boy…

End of content

No more pages to load