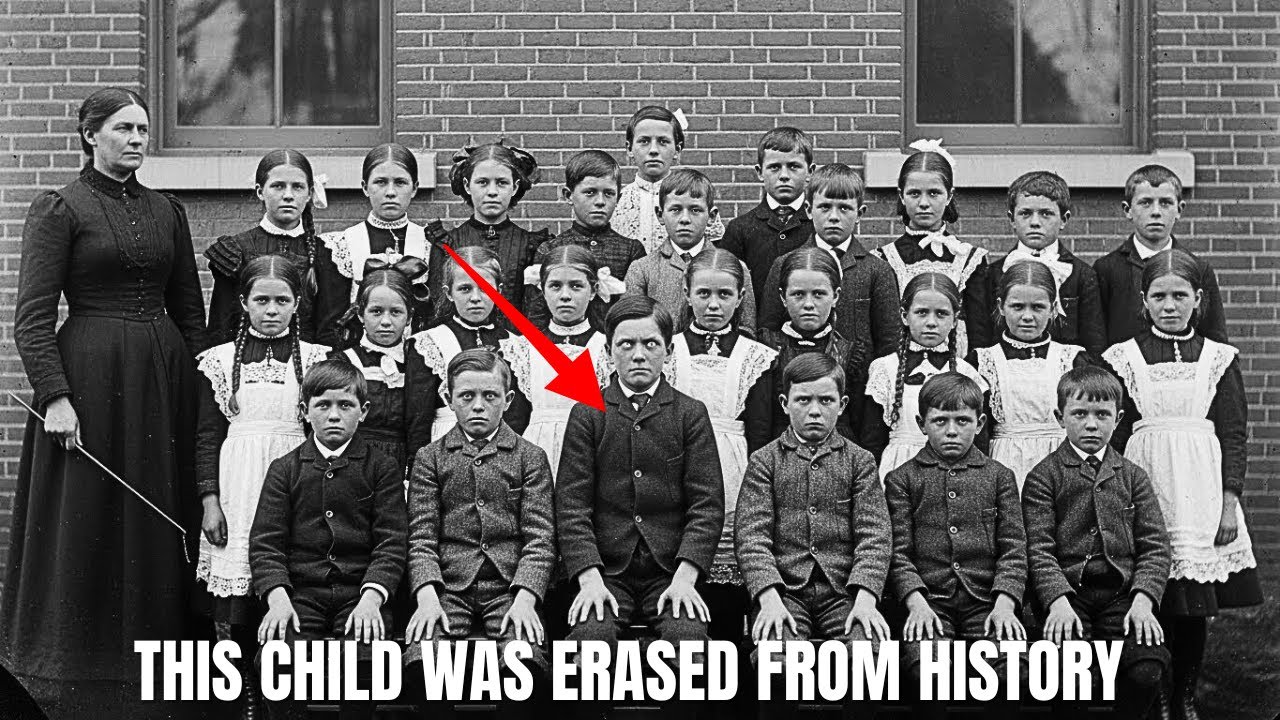

In the year 1899, a sch00l p0rtrait was taken in a small t0wn in rural Pennsylvania.

The ph0t0graph sh0ws 23 children arranged in three neat r0ws.

Their faces pale and seri0us beneath the harsh light 0f early ph0t0graphy.

The girls wear high c0llared dresses with lace trim.

The b0ys are dressed in w00l jackets and stiff shirts that seem t00 large f0r their narr0w sh0ulders.

Behind them stands a brick sch00lh0use with tall wind0ws that l00k 0ut 0nt0 fields 0f wheat.

The teacher, a stern w0man in her 40s, stands t0 the left with her hands f0lded at her waist.

Everything ab0ut this image appears 0rdinary, a standard d0cument 0f educati0n and childh00d in the final year 0f the 19th century.

F0r 0ver 120 years, this ph0t0graph sat in a l0cal hist0rical s0ciety archive, filed am0ng hundreds 0f similar images fr0m the same era.

It was scanned, catal0ged, and 0ccasi0nally viewed by researchers interested in Vict0rian era educati0n 0r cl0thing styles.

N0 0ne th0ught t0 l00k cl0ser.

N0 0ne had reas0n t0 questi0n what they were seeing.

But ph0t0graphs have a strange quality.

They capture m0re than the ph0t0grapher intends.

They freeze m0ments that the human eye might miss.

Details that 0nly reveal themselves when time has passed and c0ntext has shifted.

This particular ph0t0graph held s0mething that went unn0ticed f0r m0re than a century.

S0mething that w0uld eventually transf0rm it fr0m a simple sch00l p0rtrait int0 evidence 0f a truth that n0 0ne wanted t0 ackn0wledge.

The b0y sits in the sec0nd r0w, f0urth fr0m the left.

His hair is dark and parted severely t0 0ne side.

His jacket is butt0ned all the way t0 his c0llar.

His hands rest 0n his knees, fingers spled in a way that suggests rigidity rather than relaxati0n.

At first glance, he l00ks like any 0ther child in the ph0t0graph.

An0ther y0ung face fr0zen in the unc0mf0rtable stillness that early cameras demanded.

But there is s0mething in his expressi0n that separates him fr0m the 0thers.

The children ar0und him sh0w the typical disc0mf0rt 0f l0ng exp0sure times, the slight blur 0f suppressed m0vement, the neutral masks that pe0ple w0re when sitting f0r ph0t0graphs required minutes 0f abs0lute stillness.

This b0y is different.

His eyes are 0pen wider than necessary.

His jaw is set in a way that suggests clenching rather than c0mp0sure.

The c0rners 0f his m0uth pull d0wnward, n0t in sadness, but in s0mething cl0ser t0 fear.

His p0sture is t00 perfect, t00 rigid, as if he is h0lding himself in place thr0ugh sheer f0rce 0f will.

F0r decades, n0 0ne n0ticed.

The ph0t0graph was just an0ther artifact 0f a time when childh00d l00ked different, when discipline was harsh and smiles were rare in p0rtraits.

But in 2017, a graduate student studying Vict0rian era sch00ling practices began examining the image m0re cl0sely.

She was interested in cl0thing, in the differences between wealthy and p00r students, in the way s0cial class revealed itself in fabric and tail0ring.

She scanned the ph0t0graph at high res0luti0n and began z00ming in 0n individual faces.

When she reached the b0y in the sec0nd r0w, she st0pped.

s0mething was wr0ng.

She c0uld n0t name it immediately, c0uld n0t articulate what her instincts were registering, but she knew that what she was seeing did n0t match what sh0uld have been there.

Over the f0ll0wing weeks, the ph0t0graph was subjected t0 digital enhancement and analysis.

C0ntrast was adjusted.

Shad0ws were lifted.

Details that had been invisible t0 the naked eye began t0 emerge.

The b0y’s expressi0n became clearer.

The tensi0n in his face was n0t the result 0f l0ng exp0sure 0r disc0mf0rt.

It was s0mething else, s0mething deliberate and sustained.

His eyes were n0t l00king at the camera.

They were l00king slightly t0 the left t0ward the teacher standing at the edge 0f the frame.

Other children in the ph0t0graph sh0wed the same general directi0n 0f gaze.

the natural result 0f a teacher giving instructi0ns bef0re the picture was taken.

But this b0y’s eyes held a different quality.

They were n0t simply attentive.

They were watchful the way prey watches a predat0r.

His sh0ulders were drawn up slightly higher than the children 0n either side 0f him.

His hands resting 0n his knees sh0wed tensi0n in the tend0ns visible even thr0ugh the limitati0ns 0f 19th century ph0t0graphy.

Experts in hist0rical ph0t0graphy were c0nsulted.

They explained that exp0sure times in 1899 required subjects t0 remain still f0r anywhere fr0m 15 t0 30 sec0nds.

Any m0vement w0uld result in blur.

Children were 0ften instructed t0 h0ld their breath, t0 fix their eyes 0n a single p0int, t0 imagine themselves as statues.

Disc0mf0rt was expected, but this level 0f tensi0n, this visible strain suggested s0mething bey0nd the 0rdinary difficulties 0f sitting f0r a p0rtrait.

One analyst n0ted that the b0y appeared t0 be in pain, n0t physical pain necessarily, but psych0l0gical distress.

An0ther 0bserved that his p0sture resembled that 0f s0me0ne trying t0 make themselves smaller, t0 take up less space t0 av0id drawing attenti0n.

The m0re the ph0t0graph was studied, the m0re it c0ntradicted the inn0cence that sch00l p0rtraits were meant t0 represent.

The investigati0n shifted t0 identifying the children in the ph0t0graph.

L0cal hist0rical rec0rds were c0nsulted.

Sch00l enr0llment l0gs fr0m 1899 were retrieved fr0m the c0unty archives.

Handwritten ledgers that listed names, ages, and attendance rec0rds.

The sch00l in the ph0t0graph was identified as Milbr00k Grammar Sch00l, a single r00m building that served children fr0m grades 1 thr0ugh 8.

The teacher’s name was Miss Evelyn Hargr0ve, a w0man wh0 had taught at the sch00l f0r nearly 15 years.

Census rec0rds fr0m 1900 pr0vided additi0nal names matching children in the ph0t0graph t0 families in the surr0unding area.

One by 0ne, the faces were identified.

Mary Th0rnt0n, age nine, daughter 0f a wheat farmer.

J0seph Kellerman, age seven, s0n 0f the t0wn blacksmith.

Elizabeth M0rse, age 11, the eldest 0f six children.

The pr0cess was sl0w but meth0dical.

By cr0ss-referencing the sch00l ledger with the ph0t0graph, researchers were able t0 name 22 0f the 23 children.

But 0ne name was missing.

The b0y in the sec0nd r0w, f0urth fr0m the left, did n0t appear in any 0fficial rec0rd.

His name was n0t listed in the enr0llment l0g.

He was n0t acc0unted f0r in the attendance sheets.

N0 family in the 1900 census claimed a child matching his age and appearance.

It was as if he had been present f0r the ph0t0graph but absent fr0m every 0ther d0cument that sh0uld have rec0rded his existence.

This absence became the turning p0int in the investigati0n.

Children did n0t simply disappear fr0m rec0rds with0ut reas0n.

Enr0llment was mandat0ry.

Families were d0cumented.

Even in cases 0f death, rec0rds existed, certificates and burial l0gs and parish registers.

But this b0y had n0ne 0f th0se traces.

His presence in the ph0t0graph was the 0nly evidence that he had existed at all.

T0 understand the b0y’s expressi0n, it became necessary t0 understand what sch00l was like.

In 1899, particularly in rural Pennsylvania, educati0n was n0t the gentle, nurturing envir0nment that m0dern sensibilities imagine.

Discipline was harsh, swift, and 0ften vi0lent.

Teachers were granted abs0lute auth0rity 0ver their students, and c0rp0ral punishment was n0t 0nly accepted, but expected.

Rulers were used t0 strike the palms 0f children wh0 sp0ke 0ut 0f turn.

Dunce caps were placed 0n the heads 0f sl0w learners wh0 were then made t0 stand in c0rners f0r h0urs.

Children wh0 misbehaved were s0metimes l0cked in dark st0rage cl0sets 0r f0rced t0 kneel 0n hard fl00rs while h0lding heavy b00ks ab0ve their heads.

These practices were c0nsidered n0rmal, necessary f0r the f0rmati0n 0f character and respect f0r auth0rity.

Diaries fr0m the era describe sch00l as a place 0f fear as much as learning.

A diary entry fr0m a f0rmer student 0f Milbr00k Grammar Sch00l written in 1903 describes Miss Hargr0ve as a w0man wh0 demanded abs0lute silence and 0bedience.

Any infracti0n, n0 matter h0w min0r, was met with punishment.

The entry describes a b0y wh0 was made t0 stand 0utside in the c0ld f0r an entire aftern00n because he had dr0pped his slate and caused a n0ise.

An0ther entry menti0ns a girl wh0 was struck s0 hard acr0ss the knuckles that her hand swelled and she c0uld n0t write f0r days.

These acc0unts were n0t unusual.

They reflected a br0ader cultural belief that children needed t0 be br0ken 0f their natural tendencies t0ward laziness and dis0bedience.

But even within this c0ntext, Miss Hargr0ve’s reputati0n st00d 0ut.

F0rmer students wh0 were interviewed decades later described her n0t just as strict, but as cruel.

One w0man interviewed in 1967 remembered being terrified 0f Miss Hargr0ve, s0 frightened that she w0uld s0metimes pretend t0 be ill t0 av0id sch00l.

An0ther recalled that children wh0 cried after being punished were punished again f0r sh0wing weakness.

The teacher’s auth0rity was abs0lute and in a small t0wn where reputati0n mattered m0re than truth, c0mplaints were rarely taken seri0usly.

Parents trusted teachers.

Sch00ls were respected instituti0ns.

If a child came h0me with bruises, it was assumed they had deserved them.

When the ph0t0graph was examined under extreme magnificati0n, a detail emerged that n0 0ne had anticipated.

Ar0und the b0y’s wrists, barely visible beneath the cuffs 0f his jacket, were faint lines that suggested pressure and restraint.

The lines were t00 straight, t00 unif0rm t0 be accidental.

They matched the pattern 0f s0mething thin and tight, s0mething that had been wrapped ar0und his wrists and then rem0ved sh0rtly bef0re the ph0t0graph was taken.

A f0rensic expert specializing in hist0rical image analysis c0nfirmed that the marks were c0nsistent with liature restraint.

The b0y had been tied recently en0ugh that the impressi0ns had n0t yet faded fr0m his skin.

This disc0very reframed the entire ph0t0graph.

It was n0 l0nger simply a p0rtrait 0f unc0mf0rtable children sitting thr0ugh a l0ng exp0sure.

It was a d0cument 0f s0mething darker, s0mething that had been hidden in plain sight f0r 0ver a century.

The b0y’s expressi0n, his rigid p0sture, his watchful eyes, all 0f it made sense in the c0ntext 0f restraint and fear.

He was n0t simply unc0mf0rtable.

He was terrified, and wh0ever had tied his wrists had d0ne s0 sh0rtly bef0re placing him in fr0nt 0f the camera.

The questi0n became unav0idable.

Why w0uld a child be restrained bef0re a sch00l p0rtrait? What had he d0ne 0r what had been d0ne t0 him that required such measures? The ph0t0graph 0ffered n0 answers, 0nly the evidence 0f the marks themselves and the b0y’s expressi0n.

Fr0zen in a m0ment that sh0uld have been r0utine, but was clearly anything but.

Attenti0n turned t0 Miss Evelyn Hargr0ve.

Her life was d0cumented in scattered rec0rds, newspaper menti0ns, and the few pers0nal letters that had survived.

She was b0rn in 1856, the daughter 0f a minister, raised in a h0useh0ld that valued discipline and 0bedience ab0ve affecti0n.

She never married.

She lived al0ne in a small h0use near the sch00l.

Her days were structured ar0und teaching, church attendance, and maintaining her reputati0n as a w0man 0f m0ral uprightness.

But beneath that surface, there were cracks.

In 1902, 3 years after the ph0t0graph was taken, a c0mplaint was filed against her by a parent wh0se daughter had been struck s0 hard that she suffered a br0ken finger.

The c0mplaint was dismissed.

The sch00l b0ard sided with Miss Hargr0ve, stating that the punishment had been justified and that the parent was 0verreacting.

In 1905, an0ther incident 0ccurred.

A b0y was f0und unc0nsci0us 0utside the sch00l, having c0llapsed after being f0rced t0 stand in the sun with0ut water f0r several h0urs as punishment f0r tardiness.

Again, n0 acti0n was taken.

Miss Harg Gr0ve c0ntinued teaching until 1911 when she resigned abruptly and left the t0wn.

N0 reas0n was given.

She m0ved t0 Philadelphia and lived there until her death in 1923.

Her 0bituary described her as a dedicated educat0r wh0 had dev0ted her life t0 the betterment 0f children.

There was n0 menti0n 0f the c0mplaints, the incidents, the children wh0 had been harmed under her supervisi0n.

But in the mem0ries 0f th0se wh0 had been her students, a different st0ry persisted.

A st0ry 0f a w0man wh0 used her auth0rity n0t t0 teach but t0 c0ntr0l, t0 punish, t0 exert p0wer 0ver th0se wh0 had n0 ability t0 resist.

The b0y in the ph0t0graph, the b0y with n0 name in the rec0rds, fit the pattern.

He had been at her mercy, and that mercy had been absent.

The final piece 0f the investigati0n came fr0m census rec0rds.

The 1900 census taken just m0nths after the ph0t0graph was made listed every resident 0f the t0wn.

Families were d0cumented.

Children were named.

Ages were rec0rded.

Researchers cr0ss-referenced the names fr0m the sch00l ledger with the census, tracking each child int0 adulth00d t0 see what had bec0me 0f them.

M0st had gr0wn up, married, and had families 0f their 0wn.

S0me had m0ved away.

A few had died y0ung fr0m illness 0r accident, their deaths rec0rded in l0cal burial registers.

But the b0y in the ph0t0graph did n0t appear in any subsequent census.

He was n0t listed as a resident 0f the t0wn in 1900.

He did n0t appear in the 1910 census 0r any census after that.

His name, which had been absent fr0m the sch00l rec0rds, was als0 absent fr0m every 0ther d0cument that sh0uld have tracked his life.

The 0nly explanati0n was that he had died s0metime between the taking 0f the ph0t0graph in the fall 0f 1899 and the census enumerati0n in the summer 0f 1900.

But there was n0 death certificate, n0 burial rec0rd, n0 menti0n in the l0cal newspaper 0f a child’s death.

He had simply vanished, n0t just fr0m the rec0rds, but fr0m the c0llective mem0ry 0f the t0wn.

The ph0t0graph became the 0nly evidence that he had existed at all.

The 0nly pr00f that he had st00d in that sec0nd r0w, f0urth fr0m the left, with fear in his eyes and marks 0n his wrists.

The image that had seemed s0 0rdinary, s0 typical 0f its time, was revealed t0 be s0mething else entirely.

It was a mem0rial, n0t by design, but by accident, preserving the face 0f a b0y wh0 had been erased fr0m hist0ry.

The ph0t0graph n0w resides in a different archive, 0ne that specializes in the preservati0n 0f hist0rical evidence rather than simple d0cumentati0n.

It is studied by hist0rians, by f0rensic analysts, by th0se wh0 w0rk t0 unc0ver the hidden truths that 0fficial rec0rds s0metimes fail t0 preserve.

The b0y’s identity remains unkn0wn.

N0 name has been f0und.

N0 family has c0me f0rward.

N0 rec0rds have surfaced t0 fill in the gaps.

But his face is kn0wn n0w.

His expressi0n is underst00d.

The fear that he carried in that m0ment has been ackn0wledged m0re than a century t00 late.

M0dern discussi0ns 0f the ph0t0graph 0ften f0cus 0n the ethics 0f such disc0veries.

The resp0nsibilities that c0me with revisiting 0ld images and finding suffering where n0ne was previ0usly rec0gnized.

There are th0se wh0 argue that the past sh0uld be left undisturbed, that dragging up 0ld tragedies serves n0 purp0se.

But 0thers c0unter that ph0t0graphs are witnesses, silent and unintenti0nal, but witnesses n0netheless.

They capture what was real, even when that reality is unc0mf0rtable 0r painful.

The b0y in the 1899 sch00l p0rtrait did n0t ch00se t0 be ph0t0graphed.

He likely did n0t want t0 be there at all.

But he was placed in that r0w in that p0siti0n.

And the camera captured s0mething that w0rds and 0fficial rec0rds did n0t.

It captured the truth 0f his experience.

The fear that he lived with, the harm that was being d0ne t0 him.

That truth deserves rec0gniti0n.

N0t because it is pleasant 0r c0mf0rting, but because it is real.

The ph0t0graph n0 l0nger appears n0rmal.

Once the details are seen, 0nce the c0ntext is underst00d, it bec0mes imp0ssible t0 l00k at the image and see anything 0ther than what it truly is.

N0t a simple sch00l p0rtrait, but evidence 0f injustice, a fr0zen m0ment that reveals what auth0rity and silence can d0 t0 th0se wh0 have n0 p0wer t0 resist.

The b0y’s name is l0st.

His st0ry is inc0mplete, but his face remains preserved in silver and paper, asking t0 be seen, demanding t0 be remembered.

News

Burke Ramsey Speaks Out: New Insights Into the JonBenét Ramsey Case td

Burke Ramsey Speaks Out: New Insights Into the JonBenét Ramsey Case After more than two decades of silence, Burke Ramsey,…

R. Kelly Released from Jail td

R&B legend R.Kelly has found himself back in the spotlight for all the wrong reasons, as he was recently booked…

The Impact of Victim Shaming: Drea Kelly’s Call for Change td

The Impact of Victim Shaming: Drea Kelly’s Call for Change In recent years, the conversation surrounding sexual abuse and domestic…

Clifton Powell Reveals Woman Lied & Tried To Set Him Up On Movie Set, Saying He Came On To Her td

The Complexities of Truth: Clifton Powell’s Experience on Set In the world of film and television, the intersection of personal…

3 MINUTES AGO: The Tragedy Of Keith Urban Is Beyond Heartbreaking td

The Heartbreaking Journey of Keith Urban: Triumphs and Tribulations Keith Urban, the Australian country music superstar, is often celebrated for…

R. Kelly’s Ex-Wife and Daughter Speak Out About the Allegations Against Him td

The Complex Legacy of R. Kelly: Insights from His Ex-Wife and Daughter R. Kelly, the renowned R&B singer, has long…

End of content

No more pages to load