In 1890, a seemingly ordinary photograph captured two children standing together in a simple studio portrait.

A young girl of about nine years old held the hand of a younger boy, around five.

Their clothing was plain, their expressions solemn.

At first glance, the image appeared to be a tender depiction of sibling affection.

For more than a century, however, this photograph lay forgotten, damaged by time.

Water stains, foxing, fading, and deep creases obscured much of the image’s detail.

It remained an artifact of Victorian-era photography, unremarkable and unexamined, until 2023.

That year, a photograph restoration specialist in Vermont, tasked with digitally enhancing the image for a family history project, uncovered disturbing evidence hidden within the aged photograph.

It became immediately clear that this was no ordinary portrait.

What had long been interpreted as innocence and sibling connection was, in fact, evidence of captivity.

The girl and boy were not siblings but victims of abduction, and the photograph served as proof of a crime that had remained unsolved for over 130 years.

Emily Richardson, a professional photograph conservator in Burlington, Vermont, first encountered the photograph in August 2023.

It had been sent to her by a local resident, David Hendris, who had recently inherited a collection of Victorian-era photographs from his late aunt, Margaret Hris.

David sought professional help to preserve and identify the images.

Most of the photographs depicted ordinary family life from the late 19th century: formal group portraits, wedding photographs, and serious-faced ancestors in meticulously arranged studio settings.

One photograph, however, stood apart.

It showed a young girl and a boy standing side by side against a plain backdrop, holding hands.

A faded inscription on the back read Sarah and Thomas 1,890 May God have mercy on their souls.

The names were unfamiliar to David.

Neither Sarah nor Thomas appeared in his family genealogy, nor were there records of children dying or disappearing in his family at that time.

Emily began the painstaking work of digitally restoring the photograph.

Its condition was extremely poor.

Water damage had caused blotches and discoloration, heavy foxing obscured fine details, and the original print had several tears and deep creases.

Weeks of careful restoration revealed details that had been lost over 134 years.

The first thing Emily noticed was the children’s expressions, which were unlike typical Victorian-era portraits.

Victorian child photography often displayed serious, neutral expressions due to long exposure times and cultural conventions, but these children’s faces conveyed something far more unsettling.

The girl’s expression suggested fear rather than solemnity.

The handholding between the two children did not seem casual.

The girl gripped the boy’s hand tightly, her fingers curling firmly around his small hand.

The boy’s body language suggested that he was being held in place, not willingly posing.

When Emily enhanced the background, a horrifying detail emerged.

Behind the children, iron chains mounted to a stone or brick wall became visible, hanging at a height suitable for restraining a child.

The chains were worn and rusted, evidence of repeated use, and dark stains on the floor suggested prolonged captivity.

Shocked by her discovery, Emily contacted David.

Together, they began to investigate the origins of the photograph.

David’s aunt had kept the photograph hidden, along with a small collection of newspaper clippings that he initially overlooked.

Those clippings revealed that in September 1890, the Burlington Daily News reported the disappearance of a nine-year-old girl named Sarah Mitchell.

Her mother, Elizabeth Mitchell, was widowed and had reported her daughter missing after she vanished from the family yard.

The case received some attention in the local press, but coverage quickly shifted to other topics.

A few weeks later, Elizabeth Mitchell died of grief.

In November, newspapers reported that two children had been found dead in an abandoned house in Woodstock, Vermont, but their identities were unknown.

Sarah Mitchell’s disappearance had become part of a forgotten tragedy.

Emily and David consulted Dr.Katherine Morris, a historian specializing in Victorian-era crime at the University of Vermont.

Dr.Morris accessed archival records and found the complete case files for the Sarah Mitchell abduction.

The restored photograph, she confirmed, was likely the only surviving image of Sarah Mitchell and the boy who died with her.

The photograph had been taken by her abductor, a chilling trophy documenting the children’s suffering.

The children’s faces, restored digitally, revealed a story that newspapers had never told.

Forensic psychologist Dr.James Patterson analyzed the image, examining the facial expressions in detail.

Sarah’s eyes were wide, showing significant white above and below the iris, a physiological indicator of acute fear.

Her pupils were dilated, her eyebrows drawn together in a universal expression of distress and pleading.

Her lips were tightly pressed, pale in contrast to the photograph’s monochrome tones.

Her gaunt face, hollow cheeks, and sunken eyes indicated severe malnutrition and chronic stress.

Patterson concluded that Sarah had endured prolonged trauma, living in constant fear for weeks or months before her death.

In her eyes, the reflection of an adult male figure holding what appeared to be a cane or rod confirmed that she had been under threat of violence during the photograph.

The boy, possibly named Thomas, displayed a different but equally alarming expression.

His face was emotionless, vacant, and dissociated, showing the psychological effects of severe trauma.

His malnourished appearance was pronounced.

Both children’s clothing was dirty, ill-fitting, and torn, with stains around the collars and sleeves suggesting bodily fluids or blood.

Their wrists and hands showed markings consistent with binding or restraint.

The details revealed a life of neglect, starvation, and abuse.

The photograph’s background, when enhanced, showed a basement or cellar environment with rough stone walls, small high windows, and blocked light.

The chains on the wall were positioned as if the children had been removed from them briefly for the photograph.

On the floor were traces of what appeared to be a makeshift bedding area, and a chamber pot suggested minimal sanitation.

The image depicted a room used for prolonged captivity.

The photographic equipment, lighting, and composition indicated professional-level knowledge, suggesting that the photographer intended to document his captives deliberately.

This photograph was a trophy, created by the abductor to commemorate and share his crimes.

Archival investigation revealed the suspect.

Harold Peton, a wealthy and well-connected Burlington businessman, was identified through witness accounts as being in the area on the day of Sarah Mitchell’s disappearance.

Despite clear evidence and neighbor testimonies, the investigating detective, Robert Carrington, a friend and associate of Peton, deliberately failed to act.

The case languished unresolved.

Months later, the bodies of Sarah Mitchell and the unknown boy were discovered in Woodstock, showing signs of prolonged abuse and malnutrition.

Peton was never arrested, charged, or publicly questioned.

He died in 1903, living out his life with his crimes undetected.

Further research by Dr.Morris uncovered a disturbing pattern.

Peton was part of an organized underground network of affluent men who abducted, abused, and exploited children.

They communicated via coded newspaper advertisements, shared photographs of victims, and visited each other’s properties to participate in abuse.

The photograph of Sarah and the boy was not only a personal trophy but also a trading item within this network.

Multiple copies were produced and distributed to other members, further illustrating the organized nature of the crimes.

The provenance of the photograph explained why it survived.

Martha Hendris, a close friend of Elizabeth Mitchell, had been entrusted with Sarah’s story.

When Peton died, Martha secretly obtained the photograph from Peton’s estate.

She kept it hidden, adding the inscription May God have mercy on their souls, and preserved it along with newspaper clippings as a silent memorial.

The photograph passed through the Hendris family, generation by generation, hidden from view but never destroyed, until David Hendris sent it for restoration in 2023.

Emily Richardson’s restoration finally revealed the truth, over 130 years after Sarah Mitchell and the unknown boy suffered and died.

Their ordeal, long buried in obscurity, was made visible through modern technology and forensic analysis.

The Vermont State Police reopened the case in 2024 as a historical review, acknowledging that while Harold Peton could no longer be brought to justice, his crimes and the network he belonged to required documentation.

The photograph, now preserved by the Vermont Historical Society, serves as both evidence of past horrors and a teaching tool about child protection, abuse of power, and historical investigative failures.

Sarah Mitchell and the unknown boy who died with her are commemorated at the Vermont Children’s Memorial in Burlington.

A plaque honors them as victims of evil concealed behind societal respectability, ensuring their suffering will not be forgotten.

This story, revealed through careful restoration and historical research, offers a somber reminder of the importance of vigilance, the impact of systemic failure, and the enduring need to protect vulnerable children.

It is also a testament to the power of modern forensic photography, historical scholarship, and the perseverance of those who seek justice, even across more than a century.

The rediscovery of the photograph highlights the complex interplay between memory, family history, and the archival record.

Each generation of the Hendris family preserved a piece of the past, whether consciously or unconsciously, ensuring that one day the story could be told.

The image itself, once a hidden artifact of a horrifying crime, now provides invaluable insight into the life and suffering of two children.

It is a poignant reminder of the human capacity for cruelty and the equally vital human capacity for remembrance, compassion, and justice.

In analyzing the photograph, experts confirmed that Victorian-era children rarely displayed emotion in portraits, yet the faces of Sarah and the boy were unmistakably expressive of trauma.

The subtle but telling signs in posture, handholding, and facial tension documented not only the physical but the psychological reality of life in captivity.

Experts noted that such historical photographic evidence is rare, particularly in cases of child abduction from this period.

It provides unique insight into the lived experience of victims, going far beyond textual accounts or newspaper summaries.

The case also underscores the failure of institutions to protect the vulnerable.

The complicity of Detective Carrington, influenced by social connections and class privilege, allowed a wealthy perpetrator to evade justice.

This systemic failure had lasting consequences, silencing the story of Sarah Mitchell and countless other children who may have suffered similarly.

The photograph’s eventual discovery and restoration demonstrate how modern technology and interdisciplinary collaboration—combining photography conservation, historical research, and forensic psychology—can finally bring clarity and recognition to long-forgotten cases.

Today, the restored photograph is displayed under controlled conditions, used to educate the public about the dangers of ignoring child abuse and the historical importance of proper investigative procedures.

It serves as a memorial for victims, a warning against complacency, and a record of humanity’s darker capacity for harm.

Sarah Mitchell and the unknown boy are no longer anonymous.

Their suffering is documented, remembered, and honored.

Through the efforts of Emily Richardson, Dr.Katherine Morris, and the Vermont Historical Society, a story that could have been lost forever has become a critical lesson for history, society, and the protection of future generations.

The photograph from 1890 is a stark reminder that even in the most ordinary objects—an old photograph tucked away in a box—there can lie evidence of extraordinary human suffering.

Its restoration illustrates the power of modern technology and historical research to reveal truths that time attempted to erase.

The faces of Sarah Mitchell and the unknown boy, once hidden and silenced, now speak across the centuries, demanding recognition, empathy, and remembrance.

News

JRE: “Scientists Found a 2000 Year Old Letter from Jesus, Its Message Shocked Everyone”

There’s going to be a certain percentage of people right now that have their hackles up because someone might be…

If Only They Know Why The Baby Was Taken By The Mermaid

Long ago, in a peaceful region where land and water shaped the fate of all living beings, the village of…

If Only They Knew Why The Dog Kept Barking At The Coffin

Mingo was a quiet rural town known for its simple beauty and close community ties. Mud brick houses stood in…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Nearly three decades after the death of hip hop icon Tupac Shakur, investigators searching a residential property connected to the…

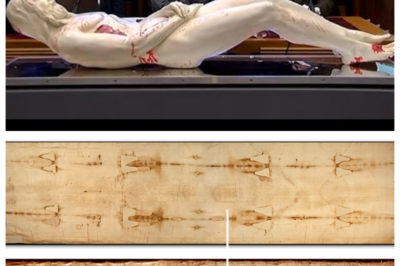

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early 2018 a group of researchers in Rome presented a striking three dimensional carbon based replica that aimed to…

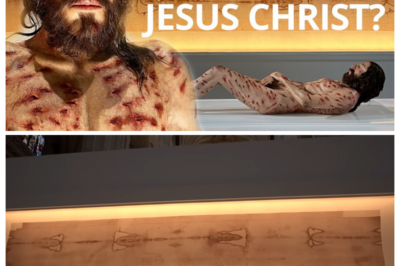

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

**The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca** For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load