In February 2024, the Victorian Family Photography Archive in Boston received a collection of 19th-century photographs and documents from the descendants of the prominent Thompson family, long known in Boston’s banking circles.

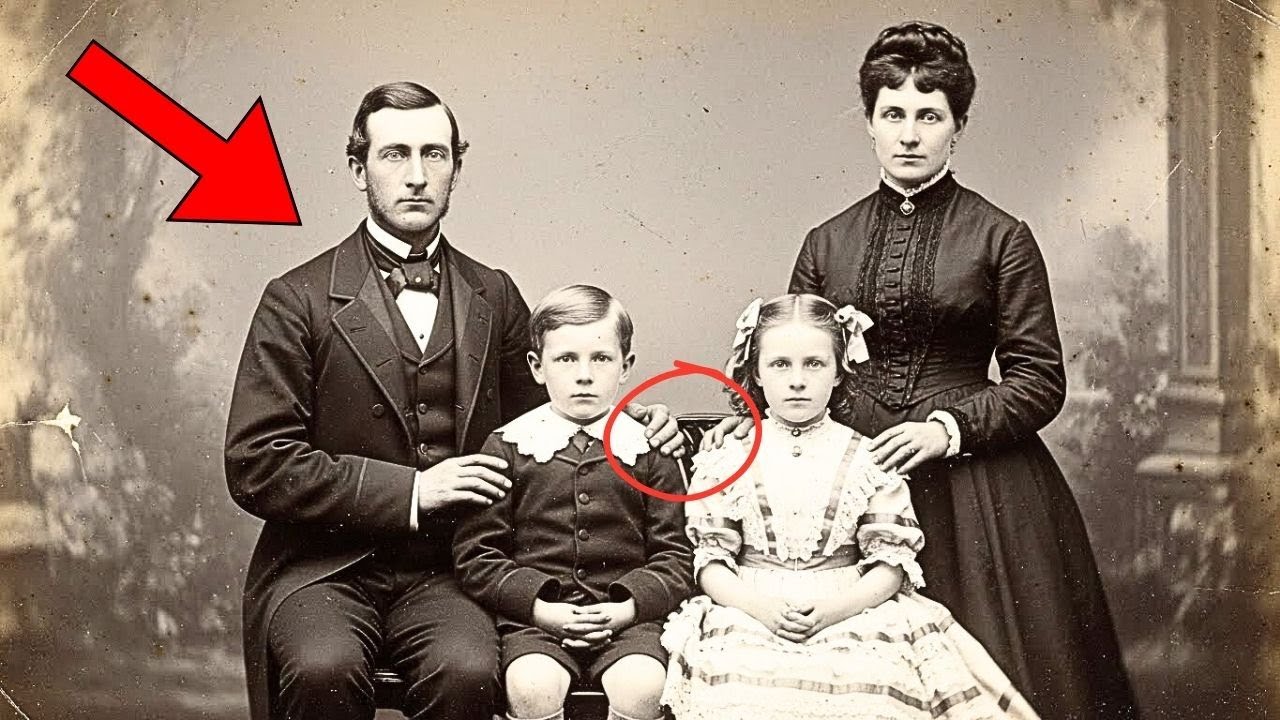

Among these items was a striking photograph dated September 1880, depicting what appeared to be a perfectly composed, formal family portrait.

The image featured a married couple standing behind their fraternal twin children, a boy and a girl, both approximately seven years old.

The family was dressed in their finest clothing, with the parents’ hands resting gently on the children’s shoulders, their poses suggesting unity, protection, and the love typical of Victorian family imagery.

At first glance, the photograph seemed to be a quintessential example of 19th-century domestic photography: a demonstration of family prosperity, refinement, and closeness.

The photograph, however, had suffered extreme deterioration over the century and a half since it was taken.

The original gelatin silver print on albumen-coated paper had become heavily discolored, faded to shades of sepia and brown, and marked by severe cracking, foxing, water damage, and edge deterioration.

As with many photographs from the era, much of the detail was lost, obscuring nuances in facial expressions, clothing textures, and the subtle interplay of light across the subjects’ faces.

Initially, the archivists and historians viewed the photograph as a formal but emotionally touching portrait of a well-to-do Boston family, unaware that beneath its surface lay a profound story of grief, loss, and Victorian mourning culture.

Dr Robert Chen, a specialist in the restoration of Victorian photographs, undertook a comprehensive digital restoration process to recover details from the extensively damaged image.

Using ultra-high-resolution infrared and ultraviolet scanning at 4,800 dpi, Dr Chen was able to penetrate the layers of degradation invisible to normal light photography.

Through sophisticated contrast enhancement algorithms and careful reconstruction of the photograph’s original tonal relationships, he revealed details long obscured, offering a glimpse into the past that had remained hidden for 144 years.

As Dr Chen worked on the children’s faces, subtle but critical differences became apparent.

The boy twin exhibited characteristics consistent with a living subject captured during the prolonged exposure times typical of Victorian studios.

Infrared imaging revealed slight asymmetries in his eyes, variations in skin tone, and micro-movements indicative of life.

The girl twin, by contrast, presented anomalies consistent with memorial photography practices common in the Victorian era.

Her face displayed unusually uniform tonal qualities, her eyes lacked the subtle asymmetries found in living subjects, and her corneas revealed a distinctive cloudiness consistent with deceased individuals.

Further examination of the children’s hands reinforced the conclusion.

While the boy’s hands showed natural variations in tension and skin texture, the girl’s were arranged with geometric precision, suggesting careful manual positioning rather than the relaxed posture of a living child.

Infrared scans revealed faint shadows behind her, indicative of a concealed posing stand—a common feature in Victorian post-mortem photography, used to support deceased subjects in natural-looking seated poses.

Even the mother’s hands resting on the girl’s shoulders, initially interpreted as a gesture of affection, appeared to assist in stabilizing the child’s body.

The evidence left no doubt: the girl twin had already died when the photograph was taken.

Historical records corroborated this revelation.

Boston death records from September 1880 confirmed that Sarah Elizabeth Thompson, age seven, died on September 14th of that year from scarlet fever.

Her fraternal twin brother, William Edward Thompson, survived the illness, albeit weakened.

Scarlet fever was a particularly deadly disease in the late 19th century, especially for children under ten.

At the time, the bacterial cause was unknown, and there were no effective treatments beyond symptomatic care.

Even the wealthiest families, such as the Thompsons, could not shield their children from its devastating effects.

The photograph, therefore, was not merely a portrait; it was a memorial image, capturing both twins together despite the tragic loss of one.

Letters preserved in the Thompson family archives reveal the parents’ motivation for commissioning such a photograph.

Catherine Thompson, the mother, insisted that William should have a record of his twin sister.

She recognized that for a surviving fraternal twin, the bond with a deceased sibling remained a central part of identity.

Edward Thompson, the father, recorded in his diary the deep sorrow and difficult decisions surrounding the photograph.

In his words, the photograph allowed the family to “pretend our family was still whole,” even in the immediate aftermath of their daughter’s death.

Victorian memorial photography was a widespread practice in the 19th century, developed in response to the high rates of childhood mortality.

Families of means often had the resources to commission post-mortem portraits, which could be carefully staged to make the deceased appear at rest and peaceful.

For twins, particularly fraternal twins of different genders, these photographs carried additional psychological and cultural significance.

They served as visual documentation of both children’s existence and preserved the twin bond in a tangible form, offering the surviving child evidence that their twin had truly existed and remained an integral part of the family narrative.

William Thompson retained the photograph for the rest of his life.

In a memoir written in 1940, he recalled the experience with poignant clarity: sitting beside Sarah, still too young to fully comprehend death, yet witnessing her presence in one final image.

He described the photograph as the only clear record of his bond with Sarah, a link to the twin identity that he had lost but could never forget.

The photograph functioned as both a memorial for the deceased child and a psychological anchor for the surviving twin, reflecting an early understanding of the complex emotional needs of children coping with sibling loss.

The technical challenges involved in creating convincing fraternal twin memorial photographs were substantial.

Unlike identical twins, where visual similarity could simplify the photographic composition, fraternal twins required careful attention to ensure that the deceased child appeared natural beside a living sibling who looked different.

Victorian photographers, often working closely with families and undertakers, developed meticulous methods to pose and support deceased subjects while maintaining a sense of realism.

In the Thompson photograph, these techniques are evident: the girl’s seated posture, the positioning of her hands, the mother’s stabilizing touch, and the concealed support structure all contribute to a portrayal of serenity and familial cohesion.

From a cultural perspective, the photograph illuminates Victorian attitudes toward childhood, death, and family identity.

Childhood mortality in the 19th century was tragically common, with estimates suggesting that one-quarter to one-third of children died before the age of ten.

Families had to reconcile profound grief with social expectations and personal desires to memorialize their children.

Photographs like the Thompsons’ served multiple purposes: they honored the deceased, provided comfort to surviving family members, and created a tangible record of family wholeness that death had temporarily disrupted.

The restoration and analysis of the Thompson photograph also underscore the advances of modern historical and forensic techniques.

Digital restoration, infrared and ultraviolet imaging, and sophisticated contrast algorithms allowed historians and conservators to detect details imperceptible in the original print.

Corneal opacity, micro-movements, hand positioning, and concealed supports—details invisible to casual observation—revealed the photograph’s true nature.

These discoveries not only clarify the history of a single family but also enhance understanding of Victorian photographic and mourning practices more broadly.

Scholars specializing in Victorian family culture emphasize the unique significance of fraternal twin memorial photographs.

Fraternal twins share an intense bond from conception through childhood, and the loss of one twin disrupts the survivor’s sense of self in profound ways.

Victorian parents and photographers recognized this psychological reality, creating images that acknowledged the twin bond while preserving the memory of the deceased sibling.

The Thompson photograph exemplifies this practice: a boy and his deceased twin sister, captured together, with parents demonstrating love and protection, and a family attempting to maintain wholeness in the face of irrevocable loss.

Modern grief psychology confirms the enduring value of such photographs.

Surviving twins often struggle with feelings of incompleteness, survivor guilt, and the challenge of maintaining a connection to their lost sibling.

Visual records, such as the Thompson photograph, provide essential evidence of existence and relationship, offering reassurance and a means to process grief.

In this sense, memorial photography transcends its role as an artistic or cultural artifact, functioning as a vital tool for emotional continuity and remembrance.

The revelation of Sarah Thompson’s death through restoration has reframed the interpretation of this photograph.

What might once have been viewed simply as a charming Victorian family portrait now carries a profound story of love, loss, and cultural practice.

The technical, historical, and psychological layers converge to make the image a testament to Victorian understanding of mortality, childhood, and family identity.

Observers today are not merely viewing a portrait of four individuals; they are witnessing a deliberate act of preservation, an attempt to hold together a family fractured by illness, and a reflection of the ways in which families have historically confronted the limits of life itself.

Ultimately, the Thompson family photograph stands as a powerful historical document.

It is evidence of parental devotion, sibling bonds, and the lengths to which families went to memorialize lost children in an era before modern medicine could prevent such deaths.

It highlights the sophistication of Victorian mourning culture, the deep significance attributed to twin identity, and the enduring human desire to preserve memories against the erasure of death.

Through the lens of modern restoration techniques, what was once a faded, deteriorated image has become a vivid story of resilience, love, and grief—a story that continues to resonate more than 140 years after it was captured.

The photograph’s modern rediscovery invites reflection on the intersection of art, memory, and mourning.

It is a reminder that images can preserve what no longer exists, providing both historical insight and emotional resonance.

For the Thompsons, the photograph immortalized Sarah and William together, a visual assertion that the twin bond transcended death.

For historians and psychologists, it illuminates Victorian approaches to grief and the unique challenges faced by surviving twins.

And for contemporary viewers, it offers a poignant meditation on the fragility of life, the depth of parental love, and the enduring power of a single photograph to convey the simultaneous presence of life and absence, love and loss.

In revealing the truth behind the Thompson family portrait, the restoration transforms an image of apparent domestic perfection into a narrative of heartbreak, resilience, and remembrance.

It underscores the Victorian understanding that children, even after death, remained integral to the family story, and that the act of photographing them served not just to memorialize, but to affirm the living bonds of memory and identity.

Through this lens, the photograph is no longer simply a static record of the past; it is a profound testament to human emotion, cultural practice, and the enduring significance of family.

News

Scientists Found DNA Code in the Turin Shroud — What It Revealed Left Them Speechless What If Microscopic Traces Hidden in the Turin Shroud Quietly Point to a Biological Mystery Science Still Cannot Explain? Advanced imaging, genetic fragments, and overlooked data suggest anomalies researchers struggled to classify. The findings raise unsettling questions about origin, age, and formation—details long debated, rarely agreed upon, and fully explored only through the article link in the comment.

For more than six centuries, one linen cloth has stood at the center of one of humanity’s most intense debates,…

Divers Found Pharaoh’s Army Beneath the Red Sea — And It’s Shocking!

For decades, the account of a dramatic sea crossing described in ancient texts has been treated by most scholars as…

Why Jay-Z Is Really Scared Of 50 Cent

The rise of Curtis Jackson, widely known as 50 Cent, marked one of the most disruptive shifts in modern hip…

What The COPS Found In CCTV Footage Of Tupac’s House STUNNED The World!

Nearly three decades after the death of rap artist Tupac Shakur, a case long labeled frozen has begun to move…

Nurse Reveals Tupacs Last Moments Before His Death At The Hospital

Twenty years after the deadly shooting that ended the life of rap artist Tupac Shakur, the public conversation continues to…

30 Years Later, Tupacs Mystery Is Finally Solved in 2026, And It’s Bad

For nearly three decades, the question of justice in the death of rap icon Tupac Shakur has moved at a…

End of content

No more pages to load