Across many of the world’s oldest cities, a quiet architectural anomaly repeats itself with remarkable consistency.

At sidewalk level, half windows emerge from stone and brick, their glass panes positioned where no interior room should logically exist.

Doorways open into earth.

Decorative arches and ironwork appear at ankle height, suggesting spaces once meant to meet the street but now submerged beneath layers of soil and pavement.

These features are often explained away as basements, coal chutes, or later modifications made to aging buildings.

Yet as researchers and observers have begun to compare cities across continents, those explanations have started to feel increasingly insufficient.

The phenomenon first draws attention in large American cities such as Chicago, where buried windows line older districts.

Similar features appear in Seattle, Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Denver.

In each case, the design is strikingly similar.

The depth below the modern street is nearly identical.

The architectural details match the buildings above rather than appearing crude or secondary.

These spaces display finished masonry, arched ceilings, decorative trim, and carefully fitted stone.

They do not resemble utility additions or hastily excavated cellars.

They resemble ground floors.

Once noticed, the pattern becomes impossible to ignore.

In Edinburgh, what is commonly called the underground city is in fact the original street level.

When the South Bridge was constructed in the late eighteenth century, the city raised its streets and buried existing buildings.

Walking through Mary King’s Close today means passing through rooms that once received daylight, complete with doorways and windows designed for street access.

Guides describe this process casually, referring to raised streets as if urban burial were a routine and unremarkable practice.

Rome presents an even more dramatic example.

The Basilica of San Clemente rests atop two earlier structures, each preserved beneath the next.

Descending through the site reveals intact churches, frescoes, and altars, all deliberately sealed and built over.

These are not ruins eroded by time.

They are complete architectural spaces intentionally buried.

Official explanations attribute this to construction practices of successive eras, yet the precision and completeness of the buried rooms suggest something more deliberate than simple replacement.

In Savannah, Georgia, the historic district sits several stories above its original ground level.

Walkways such as Factors Walk reveal merchant spaces that descend beneath modern streets.

These lower levels include windows, doorways, and finished interiors, all architecturally consistent with the structures above them.

The burial is clean and uniform, not the result of gradual accumulation.

It appears as though entire floors were intentionally filled in and built over.

This pattern extends far beyond a handful of cities.

In Istanbul, massive subterranean structures such as the Basilica Cistern display columns, arches, and spatial planning that exceed the requirements of water storage.

In London, entire neighborhoods exist below street level.

In Paris, Prague, Budapest, Vienna, Madrid, and St.

Petersburg, old buildings reveal ground floors that have become basements.

Across different climates, geologies, and political histories, the depth and design of these buried levels remain remarkably consistent.

The standard explanation is gradual accumulation.

Over centuries, cities are said to collect debris, organic material, and construction layers that slowly raise street levels.

Urban evolution, according to this view, is uneven but natural.

However, this explanation collapses under closer scrutiny.

Many medieval villages that never industrialized still have their original ground floors at street level.

These places are just as old as major cities, sometimes older, yet they show no evidence of being buried.

If gradual accumulation were universal, it would appear everywhere.

It does not.

The depth of burial also raises questions.

These are not a few inches of sediment.

Entire floors lie ten to fifteen feet below modern streets.

Such coverage would require enormous volumes of material.

Yet historical records rarely describe the sourcing, transport, or placement of this fill.

Massive earthmoving projects of this scale would have left extensive documentation, public debate, and visual records.

Instead, there is a near complete absence of transitional evidence.

Photography complicates the story further.

By the mid nineteenth century, cities were increasingly documented through photographs, illustrations, and engineering surveys.

Images captured bridges, railways, markets, and daily life.

Yet photographs showing cities mid burial are conspicuously absent.

When urban photographs begin to appear in significant numbers, the streets are already raised.

The buried windows are already underground.

The transition itself is missing from the visual record.

This absence is striking because cities undergoing supposed street raising were also experiencing rapid growth and industrialization.

Engineers documented infrastructure projects in detail.

Artists recorded urban scenes.

Newspapers reported on public works.

And yet the burial of entire neighborhoods, one of the most disruptive and labor intensive undertakings imaginable, seems to have occurred largely without comment.

Some researchers propose that these patterns point to a rapid and widespread event rather than slow accumulation.

They suggest that a catastrophic deposition of mud and sediment affected multiple regions within a relatively short time frame during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

According to this hypothesis, cities were partially buried and subsequently rebuilt on top of the debris.

The resulting layers created the underground spaces visible today.

This idea challenges conventional historical narratives and is often associated with alternative interpretations of history, including theories about forgotten civilizations.

One such concept is Tartaria, a name that appears on maps well into the nineteenth century, describing a vast territory across northern Asia.

Over time, Tartaria disappears from maps and textbooks, explained away as outdated geography or naming conventions.

Yet its sudden removal raises questions for those already examining inconsistencies in architectural history.

The buried levels themselves provide tangible evidence.

They feature ornate cornices, granite lintels, keystones, and decorative ironwork.

These are not utilitarian spaces.

They were designed to be seen and used.

In Montreal, underground corridors reveal craftsmanship equal to the structures above.

In Seattle, Pioneer Square tours pass through storefronts with original display windows, buried after the city was regraded following a fire.

The buildings above share continuous foundations with the spaces below, indicating that the lower levels were part of the original construction.

If these structures were finished and occupied before burial, the sequence of events becomes difficult to reconcile with gradual accumulation.

It suggests rapid infilling rather than slow buildup.

It suggests that cities chose to build over buried spaces instead of excavating them, perhaps due to scale, cost, or urgency.

A troubling question follows.

How did cities across continents, governed by different authorities, respond in similar ways at roughly the same time.

Edinburgh raised its streets in the late eighteenth century.

American cities followed in the nineteenth.

European cities show comparable patterns.

The techniques and depths are similar.

Official histories treat each case as a local decision driven by local conditions.

Yet when viewed globally, the uniformity suggests a shared response to a shared problem.

Disasters often appear at key moments.

Fires, floods, and earthquakes precede major rebuilding efforts.

These events provide justification for regrading and burial.

Yet they do not explain why new street levels were set at specific heights, nor why filling in existing floors was preferred over restoration.

The timing and consistency feel less coincidental when examined together.

Construction methods raise further questions.

The buried architecture often displays precision masonry and stonework that modern builders acknowledge would be difficult to replicate without advanced tools.

Massive granite blocks were quarried, transported, and fitted with extraordinary accuracy.

Official explanations cite ramps, pulleys, and manual labor, yet the absence of failed attempts or developmental stages suggests a level of mastery that appears suddenly rather than gradually.

This leads to speculation that builders were working from inherited knowledge rather than developing techniques from scratch.

Architectural styles appear fully formed in the historical record, with little evidence of experimentation.

Such patterns imply continuity from an earlier tradition that is no longer acknowledged.

Perhaps most unsettling is the speed at which these buried spaces were forgotten.

They were not ancient ruins rediscovered centuries later.

They were familiar environments within living memory.

And yet within a generation or two, their original purpose faded.

They became curiosities, tourist attractions, or unexplained anomalies.

The normalization of their existence replaced inquiry.

Observers are left with persistent questions.

Why were these spaces buried so uniformly.

Why did it happen so quickly.

Why is the process so poorly documented.

Why do explanations rely on assumptions that fail to address the physical evidence.

The underground windows remain visible reminders that something fundamental is missing from the story.

The evidence does not conclusively prove a lost civilization or a global catastrophe.

However, it clearly challenges the idea that urban burial was a slow, organic process occurring independently in each city.

The patterns suggest coordination, urgency, or response to an event not fully acknowledged in mainstream history.

Ultimately, the buried architecture invites reconsideration rather than certainty.

It calls for deeper investigation, open examination of evidence, and willingness to question comfortable explanations.

Beneath modern streets lies a layered world of finished spaces, sealed rooms, and unanswered questions.

Whether the result of disaster, deliberate burial, or forgotten history, these structures persist beneath our feet, waiting not to be explained away, but to be understood.

News

Before He Dies, Mel Gibson Finally Admits the Truth about The Passion of the Christ

**Mel Gibson Reveals the Disturbing Truth Behind The Passion of the Christ** Mel Gibson has come forward to share a…

Joe Rogan CRIES After Mel Gibson EXPOSED What Everyone Missed In The Passion Of Christ!

Mel Gibson’s Revelation on The Passion of the Christ: A Moment of Truth In a recent episode of The Joe…

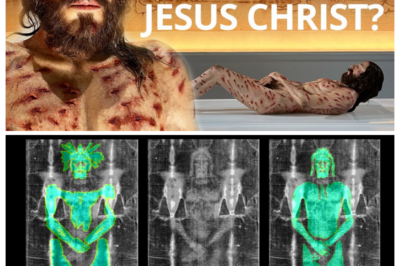

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

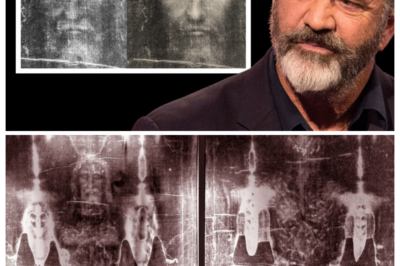

Mel Gibson: “They’re Lying To You About The Shroud of Turin!”

Mel Gibson and the Shroud of Turin: Unveiling New Insights The Shroud of Turin has long been a subject of…

Secret Vault Under the Vatican Opened After 5000 Years & It Holds Terrifying Discovery

Unveiling the Secrets of the Vatican Archives The Vatican Archives have long been shrouded in mystery, holding some of the…

Shroud of Turin Expert: ‘Evidence is Beyond All Doubt’

Perhaps no religious artifact on planet Earth creates as much fascination and controversy as the shroud of Turin. Is this…

End of content

No more pages to load