For more than four centuries, one of the most mysterious and studied artifacts in human history has been kept under strict protection inside the Cathedral of Turin.

Behind a bulletproof glass case lies a linen cloth whose origins remain uncertain, bearing markings that have puzzled historians, scientists, and theologians alike.

Over time, it has become one of the most revered relics in Catholicism, an object of veneration believed by millions to be the only surviving physical evidence of Jesus Christ, the man whose life and teachings shaped the course of civilization.

This artifact, known as the Shroud of Turin, is thought to be the burial cloth that covered Christ’s body following the crucifixion, preserving the image of his face in a manner that has captivated human curiosity for centuries.

The first documented appearance of the Shroud dates back to the 14th century, yet its history is enveloped in a shroud of uncertainty.

The linen cloth displays the faint but unmistakable imprint of a man, and believers have long claimed that the figure is that of the Messiah.

Every attempt to trace the origins of the Shroud has led to inconclusive results, and scientific investigations over the centuries have failed to provide definitive answers.

This uncertainty has only strengthened the faith of those who view the relic as proof of Christ’s resurrection.

In the late 1980s, the Shroud’s enigmatic status seemed to reach a resolution when radiocarbon dating suggested it could not have existed during the time of Christ.

Tests performed on a small sample of the cloth indicated that it was created between 1260 and 1390 AD, more than twelve centuries after the death of Jesus.

For decades, these results reinforced the belief of skeptics that the Shroud was a medieval creation, possibly designed as a pious forgery to inspire devotion.

Yet despite this apparent conclusion, the Shroud’s mystery refused to die.

In 2024, interest in the Shroud reignited following a controversial study conducted by Italian researchers from the Institute of Crystallography in Bari.

Led by Liberato Dearo, the team applied an advanced x-ray scattering technique to analyze the cellulose structure of the linen fibers.

Their findings suggested that the Shroud could be nearly 2,000 years old, potentially dating to the time of Jesus Christ.

The researchers acknowledged that their results were contingent on the assumption that the Shroud had remained in a perfectly controlled environment for centuries, a scenario complicated by the multiple fires and relocations the cloth had endured.

Despite these limitations, their work sparked renewed debate, and social media amplified the discussion, bringing global attention back to a relic that had already inspired centuries of fascination.

According to Christian tradition, the Shroud’s story begins during the final days of Jesus of Nazareth.

The Gospels recount that he shared a final meal with his disciples, warning them of his imminent death and predicting his betrayal by one of them.

Judas Iscariot handed Jesus over to the authorities, leading to his trial and eventual sentencing by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate.

Christ was flogged, crowned with thorns, forced to carry his cross, and crucified at Golgotha.

His death marked the culmination of his earthly mission, restoring the covenant between God and humanity, according to Christian belief.

Following his death, Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus prepared Jesus’ body for burial according to Jewish customs, anointing it with myrrh and aloe before wrapping it in linen and placing it in a sealed tomb.

After three days, women visiting the tomb found it empty, signaling the resurrection of Christ.

The cloth that had wrapped his body remained, yet its fate disappears from historical records for over a thousand years.

The first reliable historical mention of the Shroud appears in the mid-14th century, when a French knight named Geoffrey de Charny displayed it in a church in Lirey, France.

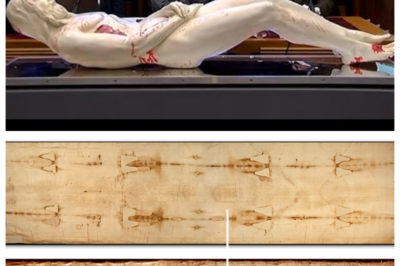

Chronicles describe the relic as a 4.4-meter-long and 1-meter-wide cloth bearing the image of a tortured man, showing wounds consistent with crucifixion.

The head displayed what appeared to be puncture wounds resembling a crown of thorns, while the back bore evidence of scourging.

Within a year of its exhibition, Pope Innocent VI recognized the public veneration of the Shroud, cementing its status as an object of religious devotion.

The Shroud changed hands several times over the centuries, ultimately finding a permanent home in Turin in 1578, where it remains today.

For nearly 300 years, it was accessible only to a select few, until Pope Gregory XVI authorized the first public exhibition in 1842.

Public interest surged further when the first photographs were taken in 1898 by the Italian lawyer and amateur photographer Secondo Pia.

His work revealed that the Shroud’s image was a negative, with details that were clearer and more defined than those visible to the naked eye.

This discovery transformed the Shroud from a regional religious curiosity into an international phenomenon.

Scientific attention to the Shroud increased in the 20th century, culminating in the Shroud of Turin Research Project in 1978.

A team of forty scientists, including physicists, chemists, microbiologists, and forensic analysts, conducted the most thorough examination of the cloth to date.

Using ultraviolet and infrared imaging, x-ray radiographs, spectroscopy, and microscopic analysis, the team confirmed that the image contained three-dimensional information, an effect impossible to reproduce with traditional painting techniques.

Chemical tests showed the blood stains were real human blood of type AB, consistent with trauma and scourging, and pollen from plants native to the Jerusalem area was embedded in the fibers.

No traces of pigments, dyes, or paints were found, challenging the notion that the Shroud was a medieval forgery.

Despite these extensive investigations, the Shroud’s origins remained unresolved.

Following the death of Umberto II of Savoy in 1983, the Shroud was bequeathed to the Vatican, establishing the Pope as its sole guardian.

This paved the way for radiocarbon dating in 1988, when samples were sent to laboratories at Oxford, Arizona, and Zurich.

The tests reaffirmed the medieval dating, placing the Shroud between 1260 and 1390 AD, seemingly confirming its status as a creation of the Middle Ages.

Nevertheless, the authenticity debate never fully disappeared.

The corner sampled for radiocarbon dating had undergone repairs after a fire in 1532, introducing the possibility that newer fibers could have skewed the results.

Scholars and scientists also noted that fires could alter the carbon balance in ancient fabrics, potentially producing misleading dates.

While the radiocarbon results remained widely accepted, doubts persisted, particularly given the Shroud’s extraordinary image, which had not been convincingly explained by natural or artificial means.

Various theories have attempted to explain how the image was formed.

Early suggestions of a medieval artist or painter failed due to the absence of pigments and the presence of detailed three-dimensional anatomical features.

A hypothesis involving a primitive photographic process, using a camera obscura and light-sensitive chemicals, was also considered but dismissed after chemical analyses found no evidence of silver salts or other photosensitive substances.

Other natural explanations, including interactions between oils used for embalming and body fluids, proved inadequate to account for the clarity and proportionality of the image.

One promising natural explanation involves the Maillard reaction, a chemical process in which sugars and amino acids react under heat to produce browning.

The surface of the Shroud’s linen contained polysaccharides derived from starch, and amino acids emitted from a decomposing body could theoretically interact with these sugars, producing a superficial discoloration on the cloth.

The reaction could explain why the image exists only on the topmost fibers, but it still fails to fully account for the anatomical precision and three-dimensional quality of the imprint.

Another explanation, embraced by some religious scholars, attributes the image to a miraculous burst of energy at the moment of Christ’s resurrection.

Laboratory experiments have shown that intense ultraviolet laser bursts could superficially mark linen in a manner resembling the Shroud’s image, though the energy levels required far exceed natural phenomena or medieval technology.

According to this interpretation, the Shroud may have captured a divine imprint of the resurrection, echoing biblical accounts such as the Transfiguration, when Christ’s face and clothing were said to shine with unearthly light.

The Shroud of Turin thus remains at the intersection of faith, history, and science.

For believers, it is an irreplaceable relic that testifies to Christ’s death and resurrection.

For skeptics, it represents a sophisticated medieval creation or a phenomenon yet to be fully explained by natural processes.

The Shroud has defied definitive categorization, challenging science and inspiring devotion alike.

The cloth’s survival through centuries of turmoil, including fires, restoration efforts, and centuries of transport, has only added to its mystique.

Despite technological advances, the Shroud resists easy explanation.

Every attempt to reproduce its unique image, whether by chemical reactions, photographic projections, or artistic methods, falls short.

Its negative image, three-dimensional properties, and anatomical detail continue to baffle researchers.

Ultimately, the true value of the Shroud may lie not in resolving the question of its authenticity but in the dialogue it continues to inspire.

It has transcended its material form to become a symbol of faith, mystery, and human curiosity.

Across generations, it has challenged the boundaries of belief and science, drawing millions to wonder at the intersection of the divine and the tangible.

Whether a medieval artifact, a relic of Christ, or a canvas of unexplained phenomena, the Shroud of Turin remains a powerful reminder of humanity’s enduring fascination with the unknown.

Its story has been shaped by centuries of devotion, scientific inquiry, and cultural fascination, and it continues to captivate the world.

The Shroud of Turin remains a silent witness to history, faith, and mystery, compelling all who study it to confront questions that may never be fully answered.

Beyond its age, origins, and method of creation, it endures as a testament to human devotion and the timeless pursuit of understanding the extraordinary.

The Shroud’s image, etched into the fabric in a manner that continues to defy explanation, is a reminder that some mysteries may never be fully solved.

Yet its enduring presence allows generations of believers, historians, and scientists to engage with a profound enigma that transcends time.

The Shroud of Turin, whether a sacred relic, a medieval masterpiece, or a miracle frozen in linen, remains a symbol of the eternal human search for meaning, bridging the gap between history, faith, and science.

News

JRE: “Scientists Found a 2000 Year Old Letter from Jesus, Its Message Shocked Everyone”

There’s going to be a certain percentage of people right now that have their hackles up because someone might be…

If Only They Know Why The Baby Was Taken By The Mermaid

Long ago, in a peaceful region where land and water shaped the fate of all living beings, the village of…

If Only They Knew Why The Dog Kept Barking At The Coffin

Mingo was a quiet rural town known for its simple beauty and close community ties. Mud brick houses stood in…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Nearly three decades after the death of hip hop icon Tupac Shakur, investigators searching a residential property connected to the…

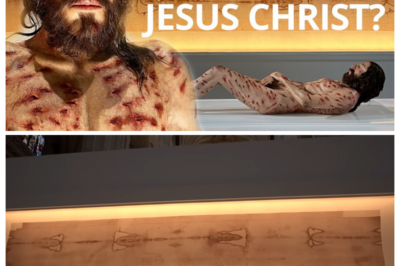

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early 2018 a group of researchers in Rome presented a striking three dimensional carbon based replica that aimed to…

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

**The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca** For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load