For decades, debates about humanity’s deep past have extended far beyond academic journals, spilling into popular culture, podcasts, and public imagination.

Among the most persistent and controversial themes is the idea that human history may be far less complete—and far less transparent—than commonly believed.

Discussions surrounding ancient giants, suppressed archaeological discoveries, and enigmatic religious relics have increasingly raised questions about whether modern institutions fully disclose what they uncover, or whether some findings are quietly set aside because they challenge established narratives.

Accounts of giants appear across cultures and eras.

In the Hebrew Bible, figures such as the Nephilim and Goliath are described as beings of extraordinary size and strength.

Other ancient traditions, from Mesopotamian tablets to Native American oral histories, speak of enormous human-like figures that once walked the earth.

Historical newspapers from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries frequently reported discoveries of unusually large skeletons uncovered during construction or excavation projects, often attributed to ancient burial mounds.

These stories, once common, largely vanished from mainstream reporting as archaeology became more centralized and professionalized.

Skeptics argue that such accounts can be explained by exaggeration, misidentification, or rare medical conditions such as gigantism, caused by pituitary disorders.

Modern medicine has documented individuals exceeding seven or even eight feet in height, lending some credibility to the idea that ancient populations may also have included exceptionally tall individuals.

Yet proponents of the giant hypothesis contend that many reports describe beings far larger than known medical cases, sometimes estimated at ten to fifteen feet tall.

This scale, they argue, suggests not isolated anomalies but a fundamentally different type of human or hominid.

The controversy deepens when institutions such as the Smithsonian Institution are brought into the discussion.

A widespread belief persists that museums and academic bodies have quietly removed evidence of giants from public view.

While no verified documentation proves systematic suppression, the perception itself reveals a growing distrust of authority.

The idea that extraordinary discoveries would be withheld until institutions could fully control the narrative resonates with a public increasingly skeptical of centralized knowledge and gatekeeping.

Underlying this suspicion is a broader concern about who controls history.

Archaeological timelines have shifted repeatedly over the past century.

Homo sapiens were once believed to have emerged around 50,000 years ago, then 150,000, then 300,000.

More recent discoveries of ancient hominin remains have pushed aspects of human ancestry back nearly a million years.

Each revision reinforces the idea that history is provisional, subject to change as new evidence emerges.

For some observers, this raises a provocative question: if a discovery radically contradicted accepted models—such as the remains of a massive humanoid—would it be publicly acknowledged at all?

For many, the issue is not merely scientific but spiritual.

Religious believers often interpret resistance to such discoveries as part of a broader effort to distance humanity from God.

Evidence that aligns closely with biblical narratives, they argue, has the potential to strengthen faith and undermine secular worldviews.

From this perspective, suppressing such evidence would serve not science, but power—maintaining control over belief systems by limiting access to transformative truths.

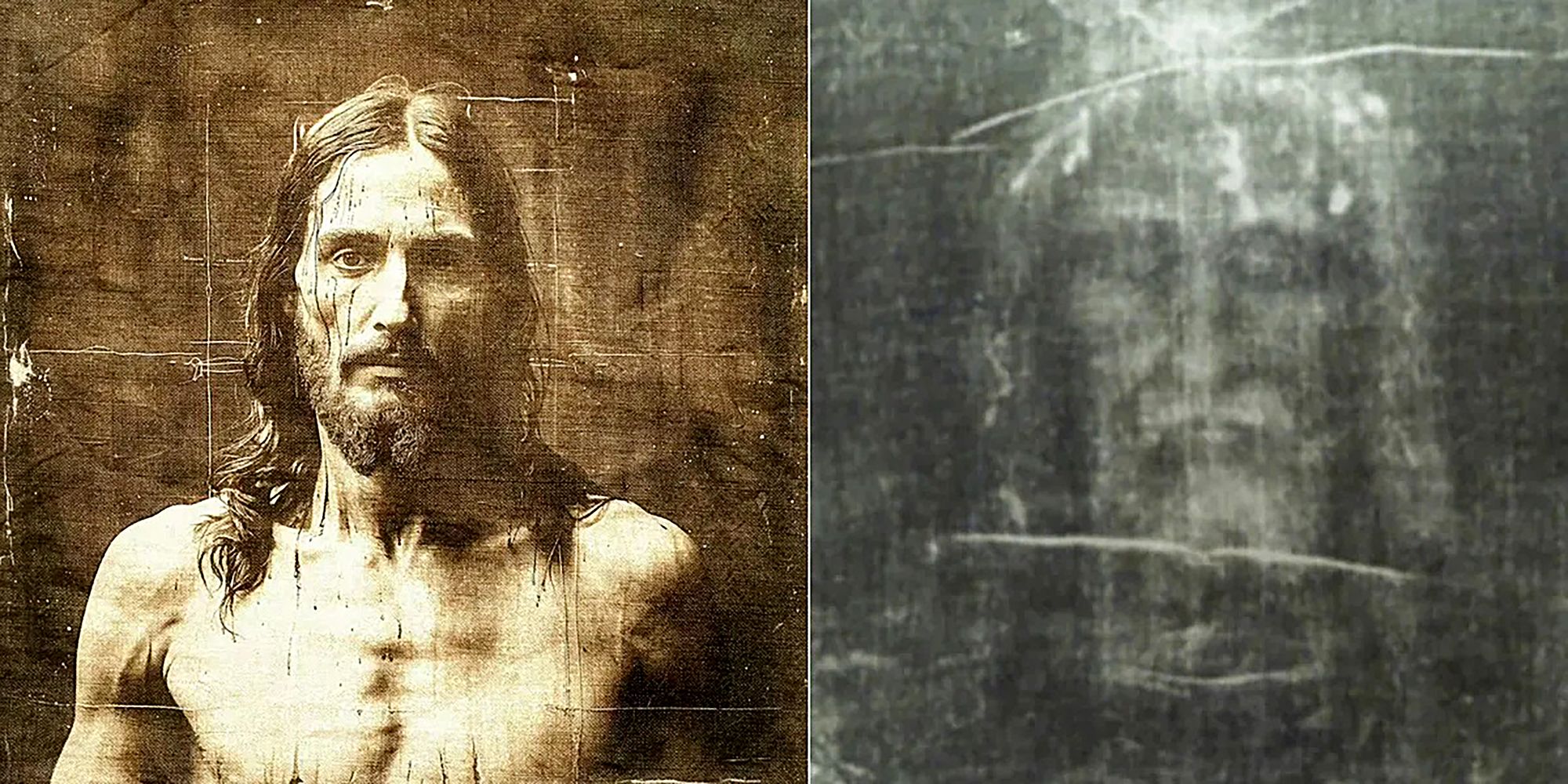

This tension between faith and authority finds one of its most striking expressions in the ongoing debate over the Shroud of Turin.

The linen cloth, bearing the faint image of a crucified man, has fascinated scientists, theologians, and skeptics for centuries.

First documented in the mid-fourteenth century, the shroud has been alternately venerated as the burial cloth of Jesus Christ and dismissed as a medieval forgery.

What makes the shroud uniquely controversial is not merely its age, but the nature of its image.

Unlike paintings or stains, the image does not penetrate the fabric.

It exists only on the surface fibers, without pigment, brush marks, or signs of conventional artistry.

When photographed in 1898, the shroud revealed an unexpected property: its photographic negative displayed a highly detailed, lifelike image, complete with facial features, wounds, and anatomical accuracy consistent with Roman crucifixion practices.

This was discovered centuries before the concept of photographic negatives existed.

Scientific attempts to replicate the image have repeatedly fallen short.

While certain forms of radiation can produce superficial discoloration on linen, the energy required to create an image of that size and detail would generate intense heat—yet the shroud shows no evidence of burning.

Carbon dating conducted in 1988 placed the cloth in the medieval period, but later criticism focused on the sampling location, which may have included repaired material rather than original fabric.

Subsequent textile and chemical analyses have produced conflicting results, leaving the question unresolved.

The shroud’s defenders argue that its details align uncannily with biblical descriptions of Jesus’ suffering: wounds on the wrists rather than the palms, scourge marks across the back, a puncture wound in the side, and blood patterns consistent with gravity and coagulation.

Critics counter that medieval artisans were capable of remarkable ingenuity.

Yet even skeptics often concede that the shroud remains one of the most studied and least understood artifacts in existence.

Beyond physical relics, ancient texts add another layer of complexity.

Much of what is known about early religious history was transmitted orally for generations before being written down.

Stories were shaped by culture, language, and belief before being recorded on parchment, animal skin, or papyrus.

Translation compounded the uncertainty.

Texts moved from Aramaic to Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and eventually modern languages, each step introducing subtle shifts in meaning.

Discoveries such as the Dead Sea Scrolls highlight both the fragility and resilience of ancient knowledge.

These texts, preserved for over two millennia, revealed remarkable consistency in some biblical passages, while also exposing variations and omissions.

Advanced techniques, including genetic testing of animal skins used for parchment, have helped scholars reconstruct how these texts were assembled.

Yet even with such precision, interpretation remains elusive.

Scholars continue to debate not only what ancient authors wrote, but what they were attempting to describe.

This uncertainty fuels speculation that some ancient accounts may reflect real events interpreted through the lens of limited understanding.

Descriptions of divine presence, overwhelming light, or lethal power—such as stories involving the Ark of the Covenant—are often cited as examples.

In biblical narratives, contact with the Ark results in sudden death, prompting some modern readers to wonder whether such stories describe unknown natural phenomena rather than purely supernatural events.

Legends surrounding the Ark persist to this day, particularly claims that it resides in a guarded church in Ethiopia.

According to tradition, only a single guardian may view it, and those who do reportedly suffer severe physical consequences.

While such stories remain unverified, they illustrate humanity’s enduring fascination with objects believed to bridge the divine and physical worlds.

At the center of all these debates lies a shared question: what actually happened in humanity’s distant past? Was there once a greater diversity of human forms? Did ancient civilizations encounter phenomena they lacked the language to explain? And if so, how much of that knowledge has been filtered, reshaped, or lost entirely?

Modern academia emphasizes caution, peer review, and reproducibility, principles essential to credible science.

Yet the public’s growing interest in alternative histories suggests a parallel hunger for meaning that transcends data alone.

Many people are less concerned with definitive answers than with the sense that important questions remain open.

Whether discussing giants, sacred relics, or ancient texts, the underlying issue is not simply evidence, but trust.

Trust in institutions to share discoveries transparently.

Trust in scholars to remain curious rather than dismissive.

And trust in humanity’s capacity to confront unsettling possibilities without fear.

At the very least, these mysteries serve as reminders of how much remains unknown.

Human history is not a closed book, but an evolving narrative shaped by discovery, interpretation, and belief.

As science advances and technology uncovers new layers of the past, it may yet force a reconsideration of long-held assumptions.

Until then, the line between myth and history remains thin, and the search for truth continues—driven as much by wonder as by reason.

News

When Jesus’ TOMB Was Opened For The FIRST Time, This is What They Found

The Unveiling of Jesus Christ’s Tomb: History, Discovery, and Impact The tomb of Jesus Christ has long stood as one…

What AI Just Found in the Shroud of Turin — Scientists Left Speechless

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has remained an enigma that fascinates both believers and scientists. This fourteen-foot-long linen cloth,…

What AI Just Decoded in the Shroud of Turin Is Leaving Scientists Speechless

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has fascinated and confounded both believers and skeptics. This nearly 14-foot-long piece of linen,…

UNSEEN MOMENTS: Pope Leo XIV Officially Ends Jubilee Year 2025 by Closing Holy Door at Vatican

Pope Leo XIV Officially Closes the Holy Door: A Historic Conclusion to Jubilee Year 2025 On the Feast of the…

Pope Leo’s Former Classmate WARNS: “This is NOT the Catholic Church”

The Catholic Church, in recent years, has faced debates and controversies that have shaken its traditional structures and practices, particularly…

Why The Book of Enoch Got Banned

The Book of Enoch remains one of the most enigmatic and controversial texts in human history. Unlike works such as…

End of content

No more pages to load