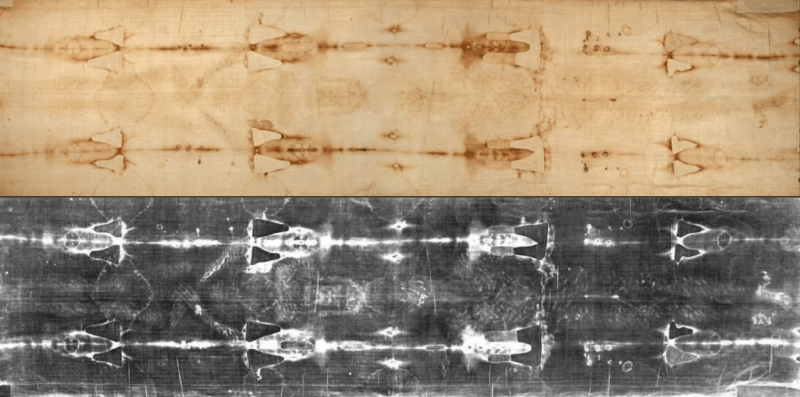

The Shroud of Turin: Evidence, Debate, and an Enduring Enigma

For more than six centuries, a length of ancient linen preserved in northern Italy has stood at the crossroads of science, history, and faith.

Known as the Shroud of Turin, the cloth bears the faint image of a crucified man and has been described by some as the most studied artifact in the world.

To believers, it may be the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth.

To skeptics, it remains a medieval object whose reputation has grown beyond what evidence can justify.

What is beyond dispute is that few relics have inspired such sustained investigation, passionate argument, and enduring fascination.

The shroud measures approximately 4.4 meters in length and one meter in width.

Across its surface appears a full-length image of a man, visible from both the front and the back, as though the body had been laid on one half of the cloth and the other half folded over him.

The figure shows signs of brutal punishment: wounds on the scalp, punctures in the wrists and feet, lash marks across the back and legs, bruised shoulders, abrasions on the knees, and a large wound in the right side of the chest.

These features closely resemble descriptions of Roman crucifixion found in the Christian Gospels.

Among the shroud’s most unusual properties is the image itself.

Under ordinary lighting, the figure is faint and difficult to discern, disappearing almost entirely when viewed from close range.

Microscopic examination has shown that the image is confined to the topmost fibers of the linen, only two to three microns thick, without penetrating deeper into the threads.

No brush strokes, pigments, dyes, or binding agents have been detected.

The discoloration appears to be the result of a chemical change in the cellulose of the fibers rather than the application of any substance.

The image acquired new significance in 1898, when Italian photographer Secondo Pia produced the first photographic negatives of the shroud.

When the plates were developed, the negative revealed a far clearer and more lifelike portrait than could be seen on the cloth itself.

Light and dark appeared reversed, giving the impression that the shroud image functions as a photographic negative.

This unexpected result drew international attention and marked the beginning of modern scientific interest in the relic.

Further investigation in the twentieth century revealed another striking feature.

In 1976 and again during the major scientific examination conducted in 1978, researchers found that the intensity of the image corresponds to the distance between the cloth and the body it once covered.

When processed by specialized image analyzers, the data produce a coherent three-dimensional representation of a human form.

Ordinary paintings and photographs do not contain such encoded depth information.

This characteristic has been central to claims that the image could not have been created by known artistic techniques.

Bloodstains on the cloth add a further layer of complexity.

Chemical and spectroscopic tests have identified hemoglobin, human albumin, serum, and other components consistent with real human blood.

The stains display serum halos, pale rings that form when blood separates into plasma and red cells, a feature rarely reproduced convincingly in art.

Some studies have suggested that the blood type may be AB, a group more common in populations from the Middle East than in medieval Europe, though this remains a subject of debate.

Notably, the blood appears reddish rather than dark brown, which some researchers attribute to elevated bilirubin levels associated with severe trauma.

Forensic specialists who have examined the image have noted its anatomical realism.

The nail wounds appear in the wrists rather than the palms, consistent with Roman crucifixion methods designed to support the body’s weight.

The scourge marks match the shape and spacing of a Roman flagrum, a whip tipped with metal or bone.

The side wound corresponds in size and position to a spear thrust delivered after death, a practice described in the Gospel of John.

The legs are not broken, again in agreement with biblical accounts that state the two criminals crucified alongside Jesus had their legs fractured, while his were left intact.

The posture of the figure suggests a body that had been suspended before burial.

The arms are slightly bent, the hands crossed over the pelvis, the head inclined forward, and the legs flexed at the knees.

Subtle distortions in the image imply that gravity had acted on the body while it was upright.

The rigidity of the limbs is consistent with early rigor mortis, a stiffness that begins shortly after death and fades within several days.

The absence of signs of decomposition has been interpreted by some as consistent with a burial interrupted before decay could begin.

Historical references to a burial cloth associated with Christ appear in the New Testament, where all four Gospels describe Jesus being wrapped in linen by Joseph of Arimathea and laid in a rock-cut tomb.

Beyond these passages, however, the documented history of the shroud becomes uncertain.

Legends speak of a miraculous cloth preserved in Edessa, in modern-day Turkey, during the first centuries of Christianity.

Known as the Image of Edessa or the Mandylion, this relic was said to bear the likeness of Christ “not made by human hands.

” Byzantine texts describe a folded cloth hidden in the city walls and later transferred to Constantinople in 944.

In the early thirteenth century, Western crusaders reported seeing a cloth in Constantinople bearing the full image of Christ’s body.

After the Fourth Crusade sacked the city in 1204, the relic disappeared from official records.

The shroud re-emerged with certainty in 1354, when it was displayed in the French town of Lirey by the knight Geoffrey de Charny.

From there it passed to the House of Savoy, suffered damage in a chapel fire in 1532, and was eventually moved to Turin in 1578, where it remains today in the Cathedral of St.John the Baptist.

The shroud’s modern scientific history reached a turning point in 1978, when the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) conducted an unprecedented series of tests.

Over five days, a multidisciplinary team employed X-ray fluorescence, infrared spectroscopy, ultraviolet imaging, microchemical analysis, and high-resolution photography.

Their principal conclusion was that the image was not painted, printed, dyed, or produced by any known artistic method.

They found no evidence of pigments, binders, or directional brush marks, and no penetration of color into the threads.

The team acknowledged, however, that they could not determine how the image had been formed.

The most serious challenge to authenticity came in 1988, when small samples taken from a corner of the cloth were subjected to radiocarbon dating by laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Tucson.

All three produced dates between 1260 and 1390, apparently placing the shroud firmly in the Middle Ages.

The announcement was widely interpreted as decisive proof of a medieval forgery.

In the years that followed, critics and supporters alike questioned whether the tested material was representative of the entire cloth.

Textile experts later argued that the sampled corner contained a mixture of original fibers and threads added during repairs after the 1532 fire.

Chemical analysis suggested the presence of cotton interwoven with the linen, inconsistent with the rest of the shroud.

If contamination or reweaving had occurred, the radiocarbon results would have reflected the age of the repairs rather than the original fabric.

New dating approaches have since reopened the debate.

In 2022, researchers from the Institute of Crystallography in Italy applied wide-angle X-ray scattering to measure the natural aging of cellulose in linen fibers.

Comparing the shroud sample with reference textiles of known age, they concluded that the degree of structural degradation was compatible with an origin in the first century.

While the method remains novel and controversial, the study renewed calls for comprehensive retesting using multiple independent techniques.

Other lines of evidence have been cited in support of an early origin.

Pollen grains identified on the cloth correspond to plant species native to Jerusalem and surrounding regions, some of which bloom in spring, the season of Passover.

Limestone dust resembling that of Jerusalem tombs has also been reported.

The weave pattern, a herringbone twill, was rare but known in the ancient Near East and consistent with high-quality burial cloths described in Jewish sources.

More speculative hypotheses have attempted to explain the image formation itself.

Experiments with heat, chemicals, and ultraviolet lasers have reproduced partial features but failed to recreate the full combination of superficial discoloration, negative imaging, and three-dimensional encoding.

Some physicists have proposed that a brief, intense burst of radiant energy altered the linen fibers in proportion to their distance from the body.

Calculations by Italian researchers suggest that such a process would have required an enormous but extremely short-lived release of energy.

No natural mechanism capable of producing this effect in antiquity has been demonstrated.

Skeptics counter that extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence.

They note the absence of clear historical documentation before the fourteenth century, the powerful influence of medieval devotion, and the unresolved problems with dating.

They argue that unknown artistic or chemical methods could account for features now regarded as mysterious, and that later contamination may explain the presence of pollen or dust from the Middle East.

Supporters respond that the convergence of anatomical accuracy, forensic detail, textile analysis, and imaging properties exceeds what could plausibly be achieved by medieval technology.

They point to the failure of modern attempts to duplicate the image and to the growing body of studies challenging the 1988 radiocarbon results.

To them, the shroud stands as a unique artifact whose properties resist conventional explanation.

Beyond questions of authenticity lies a broader cultural significance.

The shroud has shaped artistic representations of Christ, influenced devotional practices, and inspired generations of researchers.

It has become a symbol not only of suffering and death, but also of the human desire to reconcile faith with empirical inquiry.

Whether regarded as a sacred relic or a remarkable historical object, it continues to bridge disciplines that rarely meet on common ground.

For the Catholic Church, the shroud is venerated but not formally declared authentic.

Church authorities emphasize that Christian faith does not depend on the relic, and that the Resurrection rests on scriptural testimony rather than material evidence.

Public exhibitions are rare, intended to balance devotion with conservation of the fragile cloth.

As analytical techniques advance, future studies may clarify aspects of the shroud’s age, composition, and image formation.

Yet it is unlikely that every question will be resolved.

The shroud occupies a space where certainty remains elusive, inviting both belief and doubt.

In that tension lies much of its enduring power.

Whether it proves to be the burial cloth of Jesus or an extraordinary creation of later centuries, the Shroud of Turin stands as one of history’s most compelling enigmas.

Its faint figure, impressed on fragile linen, continues to challenge assumptions about art, science, and the limits of human understanding.

In doing so, it reminds observers that some mysteries endure not because they escape study, but because they invite it without end.

News

Governor of California Loses Control After Target’s SHOCKING Exit Announcement Sophia Miller

Target’s California Exit Signals Deeper Crisis in the State’s Retail Economy By Staff Correspondent For decades, California has been considered…

Mary is NOT Co-Redemptrix! Pope Leo and The Vatican Just Drew a Line

Vatican Clarifies Marian Titles: Drawing New Boundaries in Catholic Theology In a move that has stirred widespread discussion across Catholic…

The Face of Jesus Revealed In the Shroud of Turin Linen Cloth of Jesus? What Does the Evidence Say?

The Shroud of Turin and Artificial Intelligence: New Claims, Old Questions For more than a century, the Shroud of Turin…

Archaeologists Uncover Jesus’ Secret Words to Peter… Buried for 1,500 Years! ll

Unveiling the Hidden Words of Jesus: A Groundbreaking Archaeological Discovery Introduction In a remarkable turn of events, archaeologists have made…

Dr. John Campbell: “What Scientists Found on the Shroud of Turin Was Not From This Planet

The Shroud of Turin: Science, History, and an Enduring Mystery For centuries, a length of ancient linen housed in the…

California Governor Alarmed as Supply Chain Breakdown Worsens — Megan Wright Quiet disruptions are now turning into visible shortages as internal reports warn of ports backing up, warehouses stalling, and critical routes failing across the state. Emergency meetings inside the governor’s office suggest officials fear a cascading collapse no one planned for.

What triggered this breakdown, which industries are already suffering, and how close is California to a full logistics crisis? Click the Article Link in the Comments to See What the Data Is Now Revealing.

Something is beginning to fracture across California, not because of a single storm, a single strike, or a single political…

End of content

No more pages to load