For nearly two thousand years the story of the resurrection of Jesus has stood at the heart of Christian faith.

Believers around the world have read the same Gospel accounts and accepted them as complete.

According to these traditions Jesus rose from the tomb appeared to his followers and then ascended into heaven.

Yet in the ancient highlands of East Africa another tradition has quietly endured.

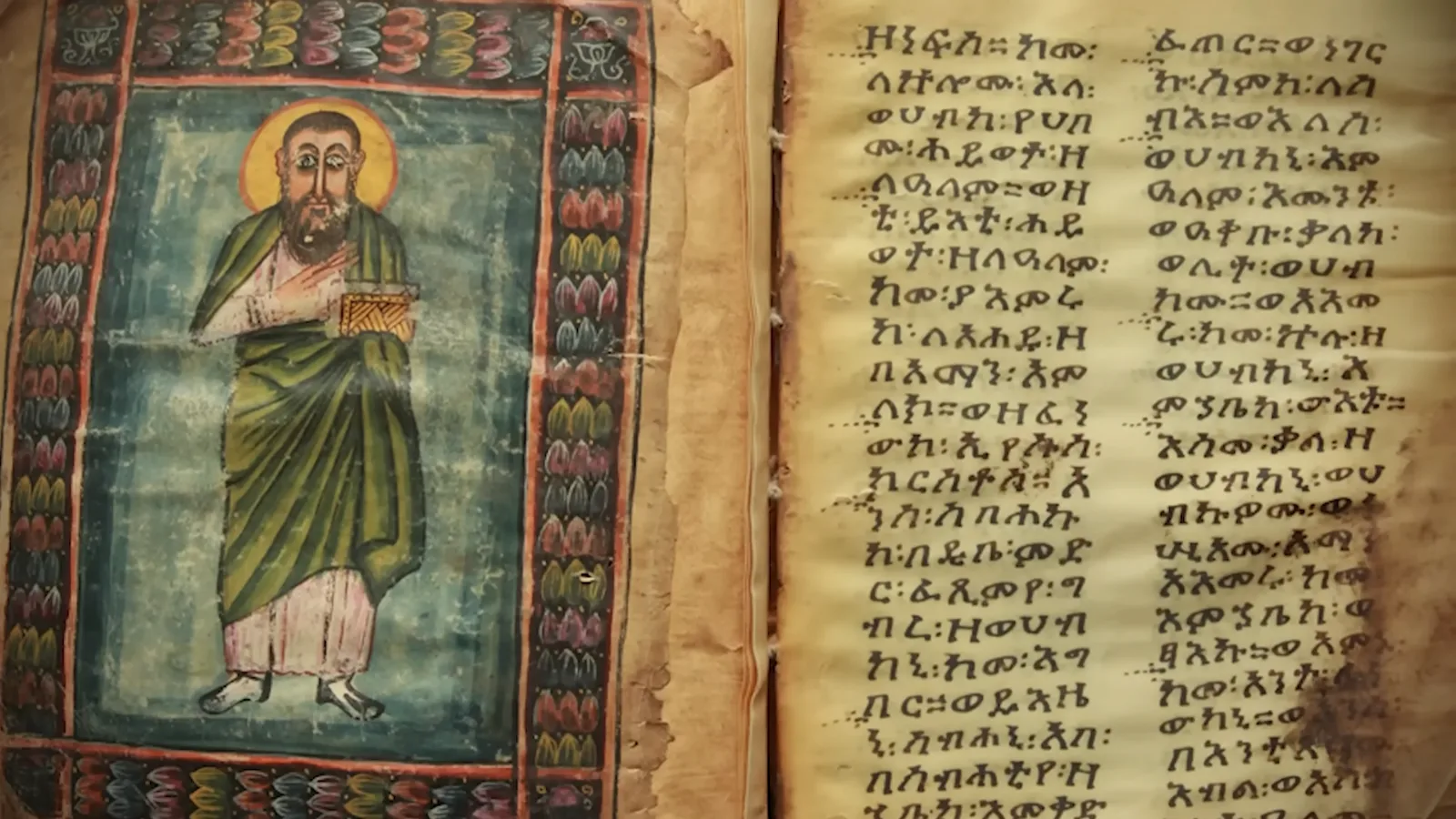

Within the Ethiopian Orthodox Church an expanded collection of sacred books preserves accounts that describe teachings of Jesus after his resurrection that never entered the Western Bible.

These writings have inspired growing interest among historians theologians and believers who seek to understand whether forgotten voices from early Christianity may still survive.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is among the oldest Christian institutions in the world.

Christianity reached the kingdom of Aksum during the fourth century and soon became the faith of the royal court and the wider population.

Cut off for long periods from Rome and Constantinople Ethiopian Christianity developed its own traditions languages and canon of scripture.

Monks copied manuscripts by hand in monasteries carved from rock or hidden in mountain valleys.

Through centuries of war drought and political change these communities protected their books with remarkable devotion.

The Ethiopian Bible remains one of the largest Christian canons in existence.

While most Protestant churches recognize sixty six books and the Roman Catholic tradition recognizes seventy three the Ethiopian canon includes eighty one books in its broader form and seventy two in its narrower form.

Among these texts are books such as Enoch Jubilees and the Book of the Covenant along with other writings that rarely appear in Western Bibles.

Some of these works describe teachings attributed to Jesus during the forty days between resurrection and ascension.

According to these Ethiopian texts the resurrection did not mark the end of instruction.

Instead Jesus continued to guide his followers speaking about faith the inner life and the future of the world.

The Book of the Covenant presents Jesus not only as teacher and prophet but as ruler of heaven and earth who sends his disciples into the world with the power of the Holy Spirit rather than weapons or political authority.

In this account the focus rests on the transformation of the heart rather than outward ritual.

The message emphasizes humility mercy and the dangers of pride and corruption.

These writings contain warnings that later generations would misuse the name of Jesus.

They speak of leaders who build great temples but neglect compassion and justice.

They describe a time when religious language becomes empty when people speak holy words but live without love.

Such passages have drawn attention because they appear to address problems that modern believers recognize in their own age.

Another influential Ethiopian text known as the Didascalia offers moral instruction attributed to Jesus and his apostles.

It urges simplicity fasting prayer and care for the poor.

It warns against leaders who present themselves as righteous while exploiting the vulnerable.

The tone reflects a community concerned less with power and more with integrity and service.

For Ethiopian tradition these teachings remain part of the living heritage of the church rather than relics of forgotten debates.

The survival of these books owes much to the isolation of Ethiopia from European ecclesiastical politics.

While councils in the Roman world debated which books should be read publicly Ethiopian monks continued copying a broader collection that reflected earlier Jewish and Christian traditions.

Canon formation in the West was gradual and complex.

Church leaders sought unity and clarity as Christianity became intertwined with imperial administration.

Texts that raised theological questions or encouraged mystical speculation were often set aside.

The Book of Enoch illustrates this process.

Widely read in Jewish communities during the time of Jesus Enoch describes angels heavenly journeys and visions of judgment.

Fragments discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls confirm its ancient popularity.

The Letter of Jude in the New Testament even refers to a prophecy attributed to Enoch.

Yet later Western leaders excluded the book from the canon perhaps because of its elaborate angelic hierarchy and cosmic themes.

Ethiopian tradition preserved it as sacred scripture.

The same pattern appears with Jubilees a retelling of Genesis and Exodus that emphasizes sacred calendars and divine order.

While this book influenced early Jewish thought it vanished from most Christian Bibles.

In Ethiopia it continued to shape theology and liturgy.

Together these texts reveal a version of early Christianity rich in symbolism mystical reflection and moral exhortation.

Modern interest in the Ethiopian canon has grown alongside renewed study of early Christian diversity.

Scholars now recognize that the first centuries of the faith produced many gospels letters and apocalypses.

Communities across the Mediterranean Africa and the Near East preserved different collections of sacred writings.

No single council created the Bible in a single moment.

Instead generations of believers debated copied and prayed over texts until a consensus emerged in different regions.

Some popular narratives claim that the Roman church deliberately suppressed secret teachings to control believers.

Historians caution against such simplifications.

They note that many excluded texts continued to circulate openly for centuries and that canon decisions reflected theological judgment more than conspiracy.

Yet the Ethiopian example demonstrates that alternative traditions survived outside the reach of imperial authority and preserved voices that might otherwise have vanished.

Among the most controversial claims associated with Ethiopian tradition is the idea that Jesus may not have died on the cross.

Certain late manuscripts sometimes called the Gospel of Peace present a Jesus who withdraws into the wilderness and continues teaching rather than submitting to execution.

These accounts emphasize healing harmony with nature and inner transformation.

They portray Jesus as a living teacher rather than a suffering redeemer.

Most historians reject these narratives as later spiritual allegories rather than historical records.

Roman sources and early Christian writings strongly attest to the crucifixion.

Yet the persistence of alternative traditions illustrates how different communities interpreted the meaning of the life of Jesus in light of their own spiritual ideals.

For Ethiopian believers these stories often function less as literal history and more as moral teaching about peace compassion and unity with creation.

The spiritual worldview reflected in many Ethiopian texts emphasizes the inner life.

These writings describe angels and demons as influences on human thought.

They teach that every action builds either a path toward light or toward darkness.

Faith is presented not as mere belief but as awakening of the spirit within.

The kingdom of God is described as present in the heart rather than confined to temples.

This inward focus resonates with broader currents in early Christianity.

Many early teachers stressed prayer silence fasting and charity as means of transformation.

Desert monks across Egypt Syria and Ethiopia pursued lives of simplicity in search of spiritual clarity.

The Ethiopian canon preserves this ascetic heritage with unusual richness.

Ethiopia itself plays a central role in these traditions.

The country claims one of the longest continuous Christian histories in the world.

According to national legend the Queen of Sheba bore a son by King Solomon who brought the Ark of the Covenant to Aksum.

While historians debate the literal truth of this story it shaped royal ideology for centuries and reinforced the sense that Ethiopia possessed a unique biblical destiny.

Unlike most African nations Ethiopia was never permanently colonized.

This independence helped preserve ancient languages liturgies and manuscripts.

The classical language Ge ez remains the medium of scripture and worship though few modern Ethiopians speak it fluently.

Thousands of manuscripts rest in monasteries many still awaiting detailed study.

The Ethiopian Bible exists in two main forms.

The broader canon includes eighty one books while the narrower canon includes seventy two.

Emperor Haile Selassie later recognized the narrower canon as official.

Even so the wider collection continues to influence theology and popular devotion.

In recent decades digitization projects and international scholarship have begun to make these texts accessible to a global audience.

Researchers compare Ethiopian manuscripts with Greek Syriac and Hebrew sources to trace the evolution of early Christian literature.

These studies enrich understanding of how diverse the early faith truly was.

For believers the significance of these writings lies not only in historical curiosity but in spiritual meaning.

They present a vision of Jesus who continues teaching after resurrection who warns against hypocrisy and who calls for humility and love.

They emphasize that truth may arise from unexpected places among the poor the forgotten and the silent.

At the same time scholars emphasize the need for careful distinction between ancient tradition and modern speculation.

Not every Ethiopian manuscript reflects first century belief.

Many texts developed over time shaped by local theology and later interpretation.

Yet even these later writings testify to the enduring desire to hear the voice of Jesus more clearly and more personally.

The Ethiopian canon thus stands as a reminder that the history of scripture is complex and multilayered.

It challenges assumptions that the Bible emerged fully formed and unchanging.

It reveals a world in which communities across continents shaped their faith through prayer debate and preservation.

Whether these extra books contain forgotten teachings of Jesus or later reflections inspired by his life remains a matter of interpretation.

What is clear is that Ethiopia preserved a remarkable library that expands modern understanding of early Christianity.

These texts invite readers to reconsider the boundaries of tradition and to appreciate the diversity of voices that once spoke about resurrection faith and the meaning of the human soul.

In a time when many seek spiritual depth beyond formal structures the Ethiopian writings offer a vision of faith rooted in inner transformation compassion and quiet perseverance.

They remind the world that the story of Jesus did not unfold in a single place or language but echoed across deserts mountains and monasteries where monks believed that every word deserved protection.

As scholars continue to study these manuscripts the legacy of Ethiopian Christianity grows ever more important.

It reveals that the voice of early faith may still be heard in places long overlooked waiting patiently for those willing to listen.

News

Madeleine McCann Was Not Abducted — Foreign Detective Bernt Stellander Tells All

Seventeen years after the disappearance of Madeleine McCann the case continues to provoke new theories renewed accusations and deep public…

Salvage Divers Found a 1.5-Mile Chariot Graveyard in the Red Sea — And It’s “Bad News”

We’re seeing that today. Truth is coming out. Whether it be Noah’s Ark or the Red Sea crossing, this is…

California Governor in MELTDOWN as 119 Companies FIRE Thousands in January — Jobs MASSACRE!

Three questions. One, if California is booming, why are layoff notices piling up? Two, if leaders care about workers, why…

Pope Leo XIV REVEALS 3 Signs Before the SECOND COMING—The Vatican Tried to HIDE This for Years

8:14 a.m. Rome time, January 22nd, 2026. Pope Leo 14th held a leather folder in his hands, dark brown, worn…

Newsom’s WARNING to Nevada After Gas Discovery | Emily Parker Emily Parker ll

Hey everyone, welcome back to the channel. I’m Emily Parker. Before we fully immerse ourselves in today’s story, I have…

Pope Leo XIV REVEALS Vatican’s DARKEST SECRET—Cardinal Burke Was LEFT IN TEARS After This! ll

The cardinal’s hands trembled as he held the folder, 30 years of silence staring back at him from faded documents…

End of content

No more pages to load