Mary Magdalene occupies a unique position in early Christian history, standing at the intersection of memory, authority, and emerging doctrine.

She is one of the few figures named consistently across all four canonical Gospels, composed between roughly 70 and 100 CE, and holds a role unmatched by any other disciple: the first recorded witness to the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, the event that became the central claim of Christianity.

Despite this prominent placement, the way her role has been remembered, emphasized, or diminished has shifted dramatically over the centuries, particularly in Western Christianity, where her importance was often minimized or morally reframed.

Yet certain traditions outside this trajectory, such as the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, offer an alternative perspective that preserves her dignity and authority in alignment with the earliest Gospel narratives.

In the canonical Gospels, Mary Magdalene appears as a follower of Jesus who provided material and practical support for his ministry.

In Mark 15:40–41, generally dated to around 70 CE and considered the earliest Gospel, she is listed among women who accompanied Jesus in Galilee and supported him during his ministry.

Matthew 27:55–56 independently confirms her presence, while Luke 8:1–3 describes her as traveling with Jesus and the Twelve, contributing materially to the movement.

John, usually dated between 90 and 100 CE, emphasizes her role as a central eyewitness in the resurrection narrative.

Though the Greek term “mathētēs,” or disciple, is not explicitly applied to her, these accounts describe her as a functional disciple: one who follows, listens, and supports the mission.

A notable detail in Luke’s Gospel states that Jesus cast seven demons out of Mary, an event often misunderstood in later Western tradition as a moral failing.

In the context of first-century Judaism, this represents healing and liberation, rather than sinfulness.

Luke situates her among a group of women from various social backgrounds, including Joanna, the wife of Herod Antipas’ steward, and Susanna, illustrating the diverse composition of Jesus’ followers.

Mary Magdalene’s role becomes particularly significant during the crucifixion.

All four Gospels note her presence at or near the site of Jesus’ execution, a dangerous and socially risky position given the public nature of Roman crucifixions.

Mark 15:40 shows her observing from a distance, Matthew mirrors this scene, Luke implies her presence among the women who followed Jesus from Galilee, and John 19:25 places her close to the cross alongside Mary, the mother of Jesus, and others.

Her repeated mention reinforces the historical plausibility of her eyewitness testimony.

Following the crucifixion, Mary Magdalene is associated with Jesus’ burial.

Mark 15:47 recounts that she and Mary, the mother of Joses, observed where Joseph of Arimathea placed Jesus’ body in a rock-hewn tomb.

Matthew 27:61 repeats this nearly verbatim, while Luke and John also link her to the burial context, though with differing emphasis.

This consistent attention to her presence at key events underscores her unique role as a primary witness.

Mary Magdalene’s most historically significant function is as the first witness to the resurrection.

In Mark 16:1–8, she arrives at the tomb after the Sabbath, bringing spices to anoint Jesus.

She discovers the tomb empty and is addressed by a young man in white, who announces the resurrection.

Matthew 28:1–10 parallels this, including an angelic appearance and an encounter with the risen Jesus.

Luke 24:1–10 names her among the women who report the empty tomb to the apostles, though their message is initially dismissed.

John 20:1–18 presents the most detailed account: Mary Magdalene arrives alone, weeping, encounters two angels, and then meets Jesus, whom she mistakes for a gardener.

Jesus commissions her to announce his resurrection to the disciples, making her the first messenger of this pivotal event.

By the early third century, theologians such as Hippolytus of Rome referred to her as the “apostle to the apostles,” an honorific highlighting her role in conveying the resurrection message.

Despite her prominence as a witness, the canonical Gospels also limit her authority.

She is never depicted teaching, interpreting doctrine, or leading Christian communities.

Unlike Peter, James, or Paul, she does not appear in the Acts of the Apostles, which chronicles the institutional expansion of the early Church.

Acts, written around 80–90 CE, centers almost exclusively on male leadership and portrays apostolic authority as linked to the Twelve and Paul’s missionary work across the eastern Mediterranean.

Her absence in Acts reflects a transition: while eyewitness testimony was preserved, formal authority and leadership roles were increasingly restricted to male figures.

Similarly, the Pauline epistles, composed between approximately 50 and 100 CE, emphasize authority through missionary labor, community governance, and doctrinal instruction, categories in which Mary Magdalene does not appear.

Early Christian memory, therefore, retained her as a foundational witness while shaping leadership along male-dominated lines.

Alternative early Christian texts reveal different portrayals of Mary Magdalene, particularly between the mid-second and fourth centuries CE.

These writings, primarily in Greek or Coptic and discovered largely in Egypt, reflect communities valuing visionary experience and interpretive insight over hierarchical authority.

The Gospel of Mary, composed circa 120–160 CE, presents her as a disciple who receives private post-resurrection teachings from Jesus and interprets complex spiritual truths for the other disciples.

Peter challenges her authority, prompting a defense by Levi that affirms her worth and spiritual insight.

This text illustrates internal disputes over leadership and the role of women in early Christian communities.

The Pistis Sophia, compiled between the late third and early fourth centuries, further emphasizes her prominence, portraying her as inquisitive and perceptive in post-resurrection dialogues with Jesus.

The Gospel of Philip, mid-third century, describes Mary Magdalene as Jesus’ companion and emphasizes their spiritual intimacy and trust, though it does not claim marriage.

These Egyptian and Alexandrian contexts were centers of theological and philosophical discourse, producing interpretations that valued spiritual insight and esoteric understanding.

Such texts were ultimately excluded from the canon during the late second to fourth centuries, not because of hostility toward Mary Magdalene specifically, but because they conflicted with emerging norms of hierarchical authority and institutionalized teaching.

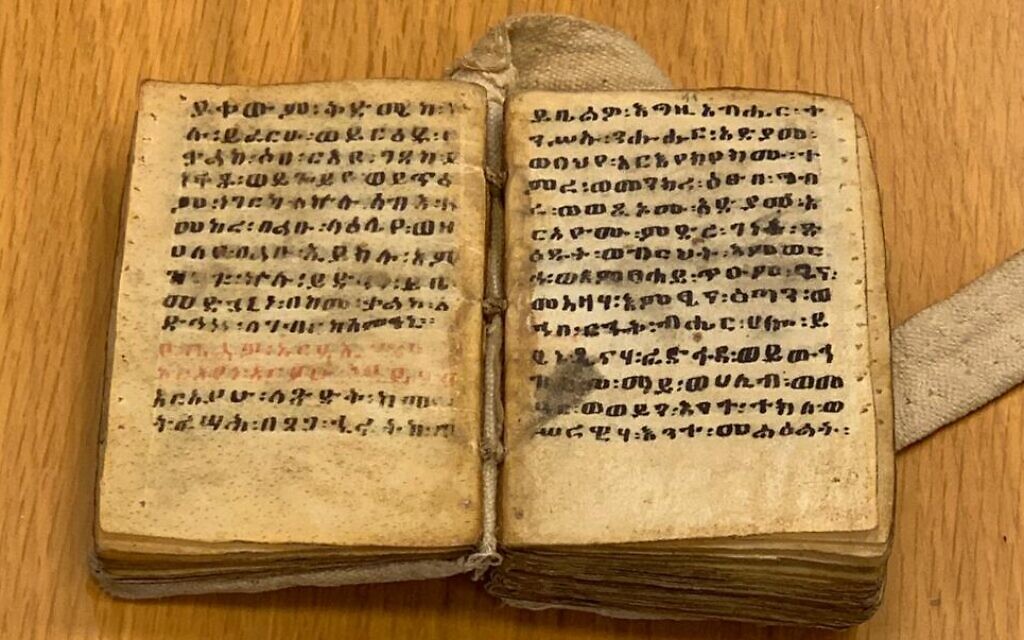

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church offers a contrasting perspective on Mary Magdalene, one that preserves her dignity and authority while remaining closely aligned with the canonical Gospels.

Ethiopian Christianity, tracing its roots to the Kingdom of Aksum in the fourth century CE, developed with relative isolation from doctrinal changes in Byzantium and Western Europe.

Its eighty-one-book biblical canon includes the standard 27 New Testament books and an expanded Old Testament collection but does not incorporate alternative gospels or secret apostolic texts.

Within this tradition, Mary Magdalene appears solely in her canonical roles: as a healed disciple, a follower, a witness to the crucifixion, a participant in the burial, and the first messenger of the resurrection.

Significantly, the Ethiopian tradition avoids the Western conflation of Mary Magdalene with the “sinful woman” in Luke 7, an identification popularized by Pope Gregory the First in the late sixth century.

Instead, Ethiopian hagiography, liturgy, and biblical commentary preserve her as a distinct figure whose authority derives from her faithful witness rather than penitential narrative.

The Sénkéssar, Ethiopia’s synaxarium of saints’ commemorations, emphasizes her steadfastness at the crucifixion and her role in announcing the resurrection, without adding or reinterpreting her biography.

During Holy Week and Paschal observances, her presence at the empty tomb is celebrated as a fulfillment of divine trust, reflecting her canonical importance without moralized reinterpretation.

This preservation reflects Ethiopia’s geographic and cultural isolation following the rise of Islam in the seventh century, which shielded its tradition from later Western interpretive developments.

The Ethiopian Church’s memory of Mary Magdalene demonstrates that respect for her role could endure without resorting to alternative texts or speculative theology.

Her representation as a faithful witness and messenger illustrates an early, pre-medieval understanding that remained stable for over a millennium.

Mary Magdalene’s diminished visibility in later Western Christianity resulted less from deliberate suppression and more from the institutionalization of the Church.

By the second and third centuries, Christian communities increasingly emphasized hierarchical structures and apostolic succession, favoring texts highlighting public teaching and leadership.

Non-canonical writings that elevated women or promoted visionary authority were gradually excluded from liturgy and instruction.

While women such as Phoebe, Junia, and Priscilla appear in early writings, later ecclesiastical regulation restricted female leadership, reinforcing male-centered authority structures.

Mary Magdalene’s remembrance thus remained anchored in her witness to the resurrection, consistent with Gospel testimony, while her broader leadership potential was marginalized.

Ethiopian Christianity, in contrast, preserves a clear and respectful memory of her role, highlighting how early Christian communities could venerate Mary Magdalene’s witness without conflating her identity with moralized narratives or relegating her to secondary status.

Her story illustrates the broader dynamics of memory, authority, and canon formation in early Christianity and highlights the diversity of ways in which her significance was understood across time and geography.

Mary Magdalene emerges not as a marginal figure or a symbolic sinner but as a central witness, disciple, and herald of the resurrection, whose role continues to resonate in traditions that maintain fidelity to the earliest Gospel accounts.

News

Jeremiah Johnston: Shroud of Turin, Dead Sea Scrolls, & Attempts to Hide Historical Proof of Jesus

The Shroud of Turin is one of the most extraordinary and controversial religious artifacts in the world. Believed by many…

Woman Who Claimed to Be Madeleine McCann Found Guilty of Harassment

Woman Who Claimed to Be Madeleine McCann Sentenced for Harassment For nearly two decades, the Macan family has endured the…

Madeleine McCann Disappearance: Reports Bone & Clothing Fragments Found

New Developments in the Madeleine McCann Case: Bone and Clothing Fragments Discovered The mysterious disappearance of Madeleine McCann, a case…

Is the Shroud of Turin Real?

The Shroud of Turin: A Historical, Scientific, and Forensic Investigation The Shroud of Turin, a centuries-old linen cloth bearing the…

Shroud of Turin Expert: ‘Evidence is Beyond All Doubt’

The Shroud of Turin: Science, Faith, and the Burial Cloth of Jesus Few religious artifacts in history inspire as much…

Ramsey Family Lied: The Secrets After 28 Years Finally Come Out

Burke Ramsay: Psychological Profile and the Enduring Mystery of John Benet’s Murder On December 25, 1996, six-year-old John Benet Ramsay…

End of content

No more pages to load