For nearly two thousand years, Christianity has told a familiar story.

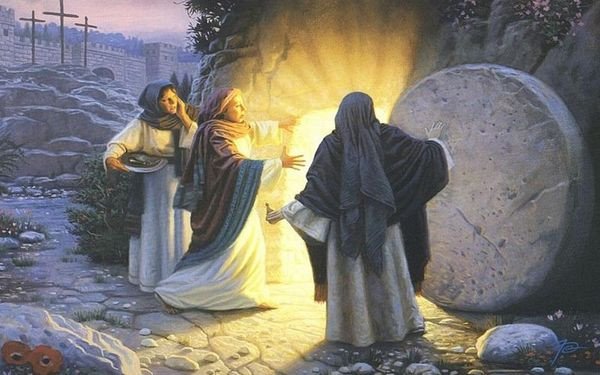

Jesus was crucified, rose from the dead, appeared briefly to his followers, and then ascended into heaven.

What happened after that, most believers assume, was silence.

The teachings were complete.

The canon was closed.

Yet in the highlands of Ethiopia, preserved in ancient monasteries and written in a sacred language older than most European alphabets, exists a version of the Bible that quietly challenges that assumption.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church maintains one of the most extensive and ancient biblical traditions in the world.

Its scriptures are written in Ge’ez, an ancient liturgical language no longer spoken in daily life but carefully preserved by clergy and scholars.

These manuscripts are not recent discoveries.

They have existed for centuries, copied by hand, guarded by monks, and treated not as curiosities but as sacred inheritance.

What makes them extraordinary is not only their age, but their content.

Unlike Western Bibles, which contain 66 books in Protestant traditions and 73 in Catholic ones, the Ethiopian Orthodox Bible contains 81 books.

This means that entire texts known only through fragments or references elsewhere remain fully preserved in Ethiopia.

Among them are writings that describe Jesus’s teachings after the resurrection in far greater detail than the familiar Gospels.

These texts do not present a gentle conclusion to the story.

Instead, they portray a final, unsettling chapter that raises uncomfortable questions about power, faith, and the future of religion itself.

The survival of these writings is rooted in Ethiopia’s unique history.

Christianity reached the Kingdom of Aksum, in present-day Ethiopia, in the fourth century, carried by missionaries from Syria and the Eastern Mediterranean.

They brought with them a wide range of early Christian literature, including texts that were later disputed, restricted, or excluded by church authorities in Rome and Constantinople.

Ethiopia, geographically isolated and politically independent, never underwent the same doctrinal consolidation that shaped Western Christianity.

It was never colonized, never forced to standardize its beliefs, and never compelled to discard texts deemed inconvenient.

As a result, Ethiopian Christianity developed along a parallel path, preserving writings that disappeared elsewhere.

Among the most significant is a collection often referred to as the Book of the Covenant, which claims to record Jesus’s teachings during the forty days between his resurrection and ascension.

In these writings, Jesus speaks not as a wandering teacher, but as a cosmic authority, issuing warnings that feel uncomfortably modern.

According to these texts, Jesus tells his followers that his message will be distorted over time.

He predicts that people will invoke his name loudly while ignoring its meaning.

He warns of religious institutions that grow wealthy and powerful while losing their moral center.

He describes temples built of stone and gold that overshadow the true temple, which he identifies as the human soul.

Faith, he insists, is not proven through public display but through inner transformation.

One passage stands out for its starkness.

Jesus blesses those who suffer for his name not through speeches or public recognition, but in silence.

The emphasis is not on authority or spectacle, but humility.

In this portrayal, Jesus consistently aligns himself with the unseen and the ignored, suggesting that truth will increasingly reside outside centers of power.

These teachings are paired with apocalyptic imagery preserved in other Ethiopian texts, most notably the Apocalypse of Peter.

While fragments of this work are known in the West, the Ethiopian version is among the most complete.

In it, Jesus reveals visions of judgment to the apostle Peter, showing him both the glory of the righteous and the torment of the corrupt.

The punishments described are graphic and specific.

Those who abuse power suffer consequences tied directly to their actions.

False witnesses, exploiters, and hypocrites are portrayed enduring fates that reflect their moral failures.

These visions are not presented as sensational threats, but as moral instruction.

The message is clear: corruption within faith carries consequences as severe as any external sin.

The emphasis is not on unbelievers, but on those who claim righteousness while acting unjustly.

It is a sharp inversion of how judgment is often framed in modern religious discourse.

Beyond warnings and visions, the Ethiopian texts also contain teachings that challenge conventional theology.

Some passages suggest that Jesus spoke about the nature of reality itself, describing the physical world as imperfect and transient, while emphasizing an eternal spiritual light that exists within all beings.

The body, he teaches, is temporary, like clothing that wears out, while the spirit endures.

True death, he explains, is not the end of physical life, but the loss of inner awareness and compassion while still alive.

Certain writings go further, presenting ideas that resemble early mystical or Gnostic traditions.

They describe a universe shaped by both light and shadow, truth and illusion.

In these accounts, Jesus’s mission is not only to forgive sins, but to awaken humanity from spiritual blindness.

Salvation is portrayed not as passive belief, but as active recognition of divine light within oneself.

This emphasis on inner awakening may explain why these texts were controversial.

Western church authorities, particularly in late antiquity and the early medieval period, sought to establish doctrinal unity.

A standardized canon helped maintain control and clarity within a rapidly expanding institution.

Texts that encouraged direct spiritual experience or questioned hierarchical authority posed a challenge to that structure.

Mystical writings were harder to regulate, interpret, and enforce.

The Ethiopian tradition offers a different explanation.

According to its scholars, these texts were rejected for three primary reasons.

First, political necessity.

A simplified canon made governance easier.

Second, discomfort with mysticism and visionary language.

And third, fear that believers might seek God without institutional mediation.

Whether one accepts this explanation or not, the historical result is undeniable: Ethiopia preserved what much of the rest of the Christian world discarded.

The cultural context of Ethiopia further reinforces this continuity.

The country is one of the oldest nations on Earth, with a continuous written history stretching back millennia.

Ethiopian tradition connects its royal lineage to the biblical Queen of Sheba and King Solomon through their son Menelik I.

According to the national epic, the Kebra Nagast, Menelik brought the Ark of the Covenant to Ethiopia, where it is believed to remain to this day in the city of Axum.

While this claim is debated, its significance lies in how deeply biblical identity is woven into Ethiopian history.

Christianity in Ethiopia was not imposed by empire.

It developed organically, integrating with existing traditions and preserving ancient practices.

While Europe experienced schisms, reforms, and inquisitions, Ethiopian Christianity continued largely uninterrupted.

The result is a faith tradition that functions as a living archive of early Christian thought.

Another reason these texts remained unknown to the wider world is linguistic isolation.

Ge’ez is understood by relatively few scholars, and until recently, many manuscripts remained untranslated.

Combined with Ethiopia’s mountainous geography and limited outside access, this created a natural barrier that protected these writings from suppression but also from global awareness.

Among the most famous preserved texts is the Book of Enoch, which describes fallen angels, cosmic rebellion, and the origins of evil.

Though quoted in the New Testament, it was later excluded from Western canons.

Ethiopia retained it in full.

Its influence can be felt throughout Ethiopian theology, shaping views on angels, demons, and moral responsibility.

Taken together, these texts present a version of Christianity that is more mystical, more demanding, and less institutional than what many believers recognize today.

They portray Jesus not as a figure who ended his mission at the resurrection, but as one who spent forty days delivering final instructions, warnings, and revelations.

Whether these writings reflect historical events, theological evolution, or spiritual symbolism remains a matter of debate.

What is certain is that they exist, and they force a reconsideration of what was included, excluded, and forgotten in the formation of the Christian Bible.

They raise difficult questions about authority, tradition, and the relationship between faith and power.

They suggest that early Christianity was more diverse, more contested, and more complex than later narratives allow.

The Ethiopian Bible does not offer easy answers.

Instead, it presents a challenge.

It asks whether faith is meant to be managed or lived, inherited or awakened.

It asks whether truth always resides in institutions, or whether it sometimes survives on the margins, guarded by those with no interest in control or recognition.

Nearly two thousand years later, these ancient manuscripts continue to speak.

Not loudly, not forcefully, but persistently.

The question they pose is not only what Jesus said after his resurrection, but why those words were forgotten—and whether the modern world is prepared to hear them now.

News

Bob Lazar Warns AGAIN: New Buga Sphere X-Rays Confirm His 1989 Warning..

In March 2025, a short and unremarkable video quietly surfaced online and then vanished just as quickly. The clip, filmed…

Rob Reiner’s Wife’s Final Report Exposes 7 Chilling Details No One Expected

A newly released surveillance video has added an unsettling new dimension to the investigation surrounding the deaths of Rob Reiner…

Nick Reiner’s 5 Best Defenses in Parents’ Disturbing Murders

The double homicide case involving Nick Reiner has rapidly evolved into one of the most closely watched criminal proceedings in…

After the Murders, What Nick Reiner’s Actions Tell Us

In the aftermath of the brutal killings of Rob and Michelle Reiner, public attention has shifted from the shocking nature…

NBA Legends You Didn’t Know Had Deadly Diseases

Professional basketball is often celebrated as a showcase of peak human performance. Speed, strength, endurance, and resilience are placed on…

1 MIN AGO: Palace CONFIRMS Camilla’s Cruel Move Against Catherine — William Furious

Tensions at Buckingham Palace: The Controversial Move by Queen Camilla Recent reports have emerged from Buckingham Palace, stirring up significant…

End of content

No more pages to load