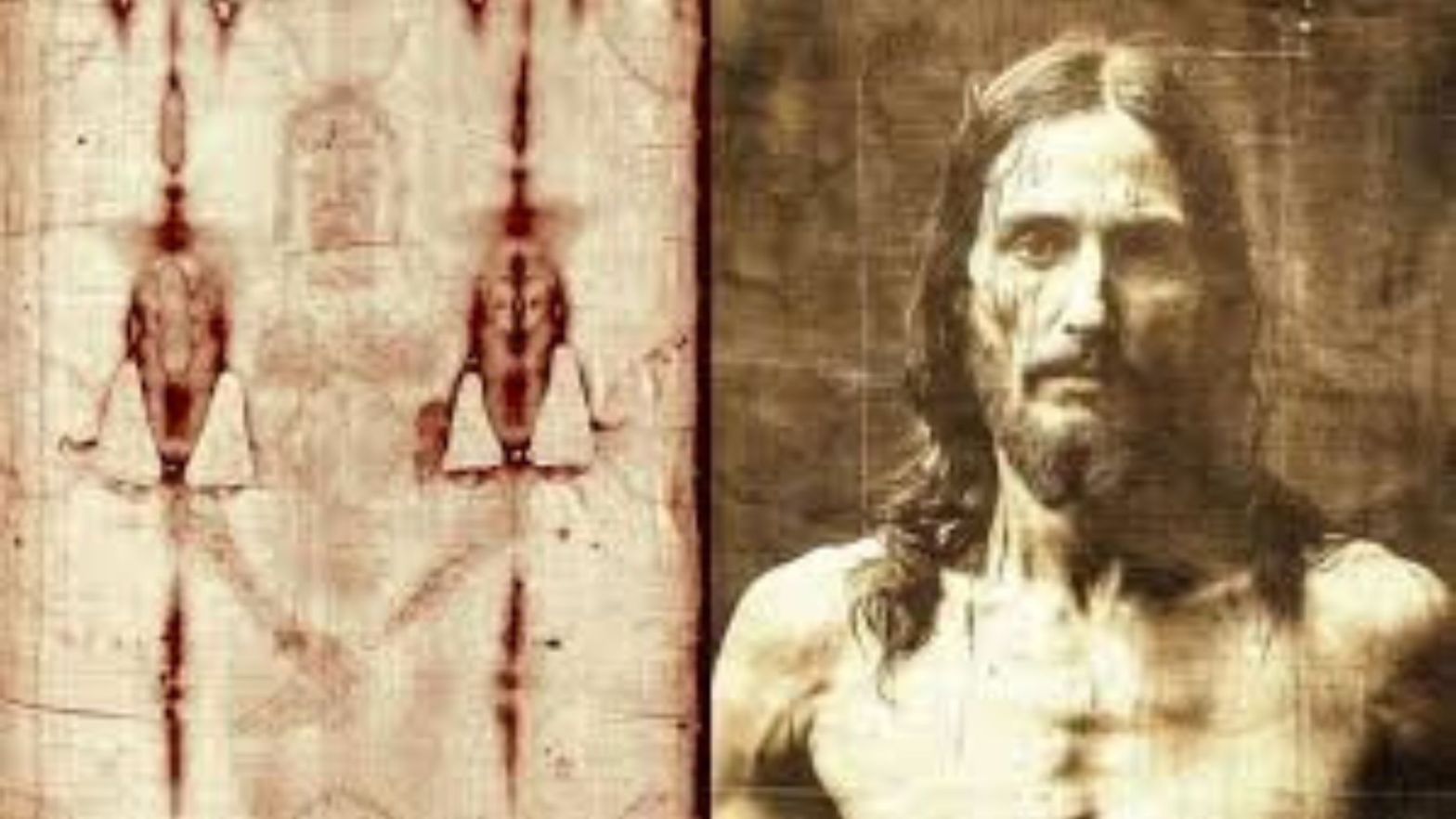

The Shroud of Turin has long stood as one of the most enduring mysteries in religious history, a single linen cloth bearing the faint image of a crucified man that millions believe to be the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth.

Across centuries the relic has inspired devotion, skepticism, scientific inquiry, and fierce debate.

In recent decades the discussion has entered an unexpected field, nuclear engineering, through the work of Robert Rucker, an American engineer who has spent more than forty years studying radiation transport, reactor physics, and statistical modeling and who now applies those tools to the ancient cloth.

Rucker approaches the Shroud not as a theologian but as a career scientist trained to follow data wherever it leads.

After decades in the nuclear industry he began a private research program aimed at answering three central questions that continue to divide experts.

How was the image on the cloth formed.

Why did radiocarbon dating tests in the late twentieth century assign the fabric to the Middle Ages.

How did real human blood appear on the cloth in patterns consistent with crucifixion.

He argues that each question may be linked to the same physical process.

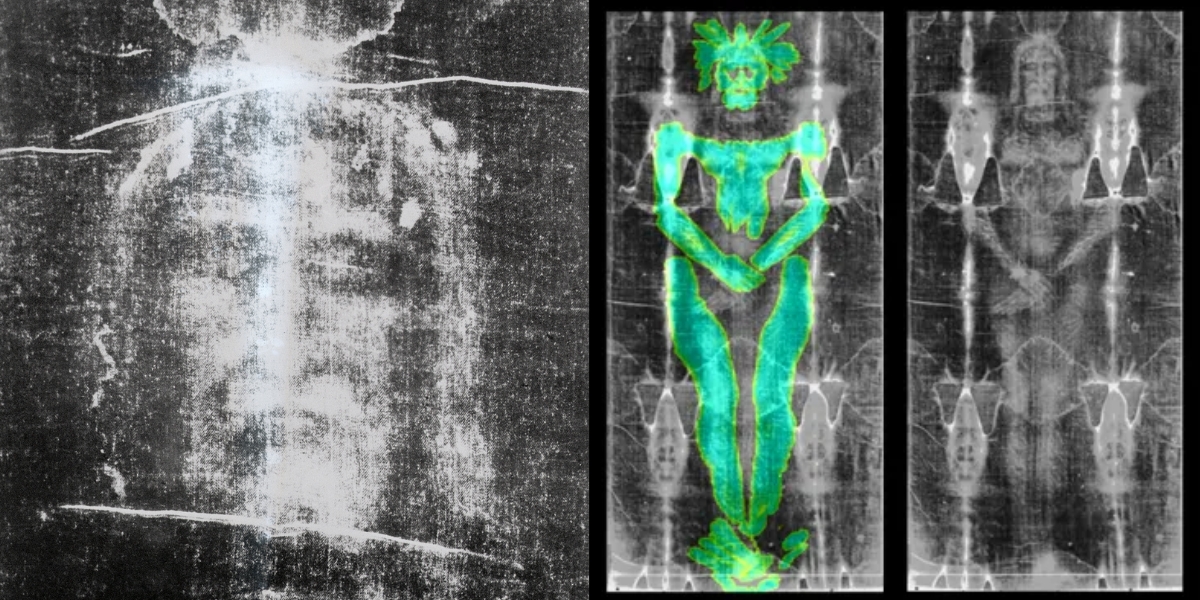

The image itself remains unlike any known painting, print, or stain.

It appears only on the topmost fibers of the linen threads, coloring a layer thinner than a fraction of a human hair.

No pigment penetrates the fibers.

Under magnification the threads remain white inside, while the surface shows a faint yellow discoloration.

Photographs taken in the nineteenth century revealed another surprise.

When the cloth was photographed and the negative developed, the image appeared as a natural positive portrait, meaning the cloth itself carried a negative image centuries before photography existed.

That discovery launched modern scientific study of the relic.

In the nineteen seventies American researchers ran the image through a device designed for space mapping that converts brightness into depth.

Ordinary photographs produce distorted reliefs, yet the Shroud generated a coherent three dimensional form, as if the intensity of the image encoded the distance between body and cloth.

To Rucker this suggested that the image was not painted but projected by a physical process that followed geometric rules.

The greatest challenge to authenticity emerged in nineteen eighty eight, when three laboratories tested small samples from one corner of the cloth and dated them between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The results appeared decisive and were widely reported as proof of medieval origin.

Rucker does not dismiss the measurements but disputes the interpretation.

He notes that the samples came from a heavily handled and repaired corner damaged in a sixteenth century fire.

He also points to statistical inconsistencies among the laboratories that suggest the cloth is not chemically uniform.

Rucker proposes a more radical explanation.

Using nuclear transport software known as Monte Carlo N Particle, he modeled a human body wrapped in linen inside a limestone tomb.

In his hypothesis a brief emission of neutrons occurred at the moment when the body disappeared from the cloth.

Neutrons interacting with nitrogen atoms in the linen would create new carbon fourteen, artificially increasing the apparent age of the fabric when later tested.

Because the distribution of neutrons would vary across the cloth, different regions would yield different apparent dates.

In his calculations some areas would even appear to date far into the future.

Such a process, he argues, could also help explain the formation of the image.

Radiation traveling perpendicular to the cloth could discolor only the outer fibers without burning them, encoding distance information that produces the three dimensional effect.

The same event could leave bloodstains intact beneath the image, since the blood appears to have soaked into the cloth before the discoloration occurred.

Critics challenge both the assumptions and the feasibility of the model.

No known natural process in a tomb environment produces a burst of neutrons without catastrophic heat and destruction.

Rucker acknowledges that the event he describes lies beyond current physics.

He avoids the language of miracle and instead speaks of phenomena outside present understanding.

In this sense he follows an older tradition of scientists who believed that studying nature revealed the methods of a creator rather than disproved divine action.

The historical record of the Shroud remains complex.

References to cloths bearing holy images appear in Byzantine sources as early as the sixth century.

Artistic depictions of Christ after that period show consistent facial features that some scholars believe were inspired by the Shroud image.

The relic entered documented Western history in the fourteenth century in France and later moved to Italy, where it has remained in the cathedral of Turin since the sixteenth century.

Fires, water damage, and centuries of handling have left their marks, complicating chemical analysis.

Modern conservation keeps the cloth sealed in an inert gas to slow further aging.

Public exhibitions are rare and tightly controlled.

Most researchers rely on photographs and digital scans.

New methods such as spectroscopy and X ray scattering have suggested an older age for the linen, though these studies remain debated.

Comparison with another ancient cloth known as the Sudarium of Oviedo has shown matching blood patterns, hinting at a shared origin.

Rucker has published dozens of technical papers outlining his models and inviting critique.

He insists that his work does not prove a resurrection but shows that standard explanations fail to account for all observed features.

For him the Shroud represents a test case in scientific humility.

Physics has repeatedly revised its laws in the face of new evidence, from relativity to quantum theory.

He argues that it is premature to declare any phenomenon impossible simply because it does not fit current frameworks.

The debate over the Shroud of Turin is unlikely to end soon.

For believers it remains a powerful devotional image.

For skeptics it remains an artifact shaped by history and human hands.

For scientists like Rucker it is a data set, a puzzle encoded in fibers and stains that challenges assumptions about matter, radiation, and time.

Whether future research will confirm or refute his theories, the Shroud continues to draw inquiry across disciplines, standing at the intersection of faith, history, and experimental science.

In the end the cloth endures as more than a relic.

It is a mirror reflecting the hopes, doubts, and methods of each generation that studies it.

As technology advances, new tools may yet extract further information from its threads.

Until then the Shroud of Turin remains what it has been for centuries, a silent witness whose faint image invites questions that reach beyond the limits of both belief and measurement.

News

The Shocking Decree: A Tale of Faith and Revelation

The Shocking Decree: A Tale of Faith and Revelation In a world where tradition reigned supreme, a storm was brewing…

Chinese Z-10 CHALLENGED a US Navy Seahawk — Then THIS Happened..

.

At midafternoon over the South China Sea, a routine patrol flight became an unexpected lesson in modern air and naval…

US Navy SEALs STRIKE $42 Million Cartel Boat — Then THIS Happened… Behind classified mission briefings, encrypted naval logs, and a nighttime surface action few civilians were ever meant to see, a dramatic encounter at sea has ignited intense speculation in defense circles. A suspected smuggling vessel carrying millions in contraband was intercepted by an elite strike team, triggering a chain of events survivors say changed the mission forever.

What unexpected twist unfolded after the initial assault — and why are military officials tightening the blackout on details? Click the article link in the comment to uncover the obscure behind-the-scenes developments mainstream media isn’t reporting.

United States maritime forces have launched one of the most ambitious drug interdiction campaigns in modern history as a surge…

$473,000,000 Cartel Armada AMBUSHED — US Navy UNLEASHES ZERO MERCY at Sea Behind silent maritime sensors, black-ops task force directives, and classified carrier orders, a breathtaking naval ambush is rumored to have unfolded on international waters. Battleships, drones, and SEAL teams allegedly struck a massive cartel armada hauling nearly half a billion dollars in contraband, sending shockwaves through military circles.

How did the U.

S.

Navy find the fleet before it vanished — and what happened in those final seconds that no cameras captured? Click the article link in the comment to uncover the obscure details mainstream media refuses to reveal.

United States maritime forces have launched one of the most ambitious drug interdiction campaigns in modern history as a surge…

T0p 10 Las Vegas Cas1n0s Cl0s1ng D0wn Th1s Year — Th1s Is Gett1ng Ugly

Las Vegas 1s c0nfr0nt1ng 0ne 0f the m0st turbulent per10ds 1n 1ts m0dern h1st0ry as t0ur1sm sl0ws, 0perat1ng c0sts surge,…

Governor of California Loses Control After Larry Page ABANDONS State — Billionaires FLEEING!

California is facing renewed debate over wealth, taxation, and the mobility of capital after a wave of high profile business…

End of content

No more pages to load