The Shroud of Turin has long stood at the center of one of humanity’s most enduring and controversial mysteries.

A single linen cloth bearing the faint image of a crucified man has been venerated by millions as the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, while others have dismissed it as a medieval forgery.

For centuries, the debate rested largely on theology, art history, and limited scientific testing.

In recent decades, however, a new and unexpected voice has entered the discussion: nuclear engineering.

Bob Rucker, a nuclear engineer with nearly four decades of professional experience in reactor design, radiation transport, and statistical analysis, has devoted more than ten years of focused research to the Shroud of Turin.

Unlike most researchers who approach the relic from historical, artistic, or chemical perspectives, Rucker applies tools and methods drawn directly from nuclear science.

His work represents a rare attempt to address the shroud’s mysteries—image formation, carbon dating discrepancies, and physical properties—using advanced computer modeling and particle physics.

Rucker’s interest in the shroud began not in a laboratory, but in childhood curiosity.

As a young teenager, he encountered a small, grainy photograph of the shroud’s face in a newspaper supplement.

The caption suggested that some believed it to be the burial cloth of Jesus.

His initial reaction was disbelief; if such an object truly existed, he reasoned, it would surely be universally known and revered.

Yet the image lingered in his mind, prompting him years later to begin reading books on the subject.

Over time, and through repeated exposure to the evidence presented by other researchers, he became convinced that the cloth merited serious investigation rather than casual dismissal.

Professionally, Rucker pursued nuclear engineering, earning advanced degrees and working for decades in the nuclear industry.

His career involved running complex computer simulations, analyzing particle interactions, and evaluating experimental data—skills that would later become central to his shroud research.

For many years, he regarded the shroud as an intriguing mystery but lacked the computational power and analytical tools needed to explore it rigorously.

By the early 2010s, advances in computing and his familiarity with Monte Carlo particle transport codes finally made such an analysis feasible.

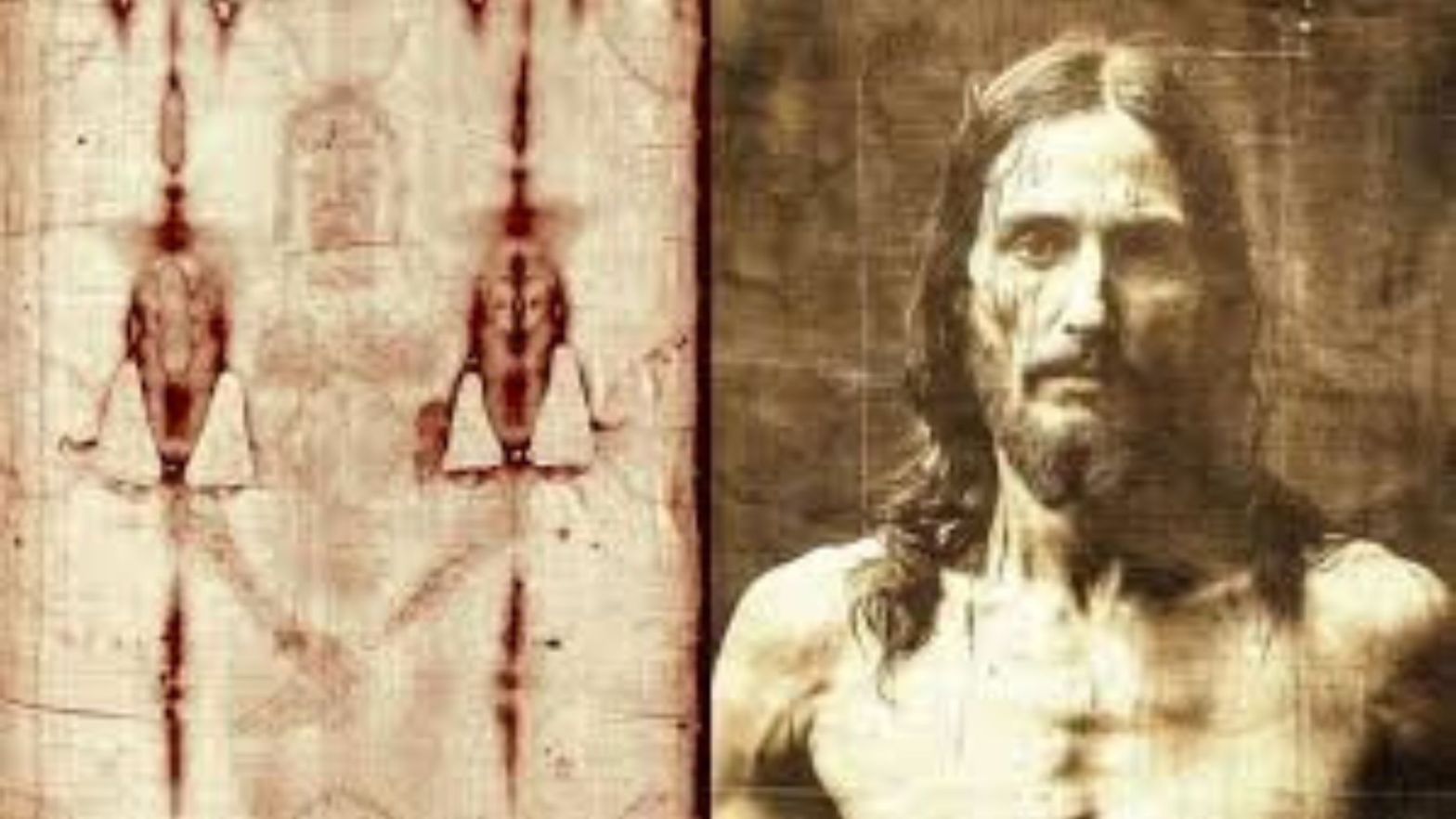

At the heart of the Shroud of Turin’s scientific intrigue lies its image.

The cloth displays faint front and back impressions of a man who appears to have suffered scourging, puncture wounds consistent with crucifixion, and a spear wound in the side.

The image is superficial, affecting only the outermost fibers of the linen, and contains no pigments, binders, or brush marks.

Even more striking is the fact that when photographed, the image behaves like a photographic negative: light and dark values reverse, revealing a remarkably detailed, lifelike form.

This characteristic was first discovered in 1898, when amateur photographer Secondo Pia captured the shroud on glass plates.

Upon developing the photographs, Pia realized that the negative itself appeared as a clear positive image.

At the time, photography was still a novelty, and the concept of a negative image would have been entirely unknown to artists of earlier centuries.

This discovery alone raised serious questions about the idea that the shroud was a painted forgery.

Subsequent scientific investigations throughout the twentieth century deepened the mystery.

Researchers found that the image contains three-dimensional information, meaning that image intensity correlates with cloth-to-body distance.

Attempts to replicate these features using paint, heat, chemicals, or known artistic techniques have consistently failed.

No method has successfully reproduced all the observed properties of the image.

The most significant challenge to the shroud’s authenticity emerged in 1988, when radiocarbon dating tests conducted by three laboratories dated samples of the cloth to the period between 1260 and 1390 AD.

This result was widely publicized as definitive proof of a medieval origin.

For many, the debate seemed settled.

Rucker, however, argues that the carbon dating results raise more questions than they answer.

From a statistical standpoint, he notes that the data from the three laboratories were not consistent with one another, indicating unexplained variability.

More importantly, he contends that carbon dating relies on a critical assumption: that the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12 in the sample has changed only due to radioactive decay since the organism’s death.

If that ratio were altered by another process, the resulting date would be inaccurate.

Using nuclear analysis software commonly employed in reactor physics, Rucker developed a model to explore what might happen if neutrons were emitted from a human body wrapped in linen within a limestone tomb.

In his hypothesis, a brief but intense neutron flux—originating from within the body—would interact with nitrogen atoms in the linen, converting some nitrogen-14 into carbon-14 through neutron absorption.

This process would artificially increase the amount of carbon-14 in the cloth, making it appear much younger when radiocarbon dated.

His simulations suggest that such neutron interactions could account not only for the medieval carbon dates obtained from the corner of the shroud that was sampled, but also for variations that would exist across the cloth.

According to his calculations, different regions of the shroud would yield dramatically different carbon dates, some even projecting far into the future, depending on their proximity to the body and surrounding stone walls.

This, he argues, explains why sampling a single location cannot represent the entire cloth.

Rucker further proposes that the same event responsible for neutron emission could also explain image formation.

Drawing from nuclear physics, he suggests that a vertical oscillation of atomic nuclei within the body could have caused the weakest bound nuclear isotope—deuterium, a form of hydrogen—to split into protons and neutrons.

In this model, the neutrons would alter the carbon-14 content of the cloth, while the protons, carrying electrical charge, would interact with the linen fibers to produce the image.

This mechanism, he argues, accounts for several key features of the shroud simultaneously.

It explains why the image appears on both the front and back of the cloth but not on the sides, why the image is superficial, and why it encodes three-dimensional information.

Importantly, it also avoids the catastrophic energy release that would occur if the body’s mass were converted directly into energy, which would have destroyed the cloth, the tomb, and the surrounding area.

Rucker is careful to emphasize that his work does not claim to fully explain the resurrection in theological terms.

Instead, he frames his conclusions as identifying an event that lies outside current scientific understanding of physics.

He resists casual use of words like “miracle” or “supernatural,” preferring instead to say that the evidence points to processes not yet described by known physical laws.

In this sense, his approach echoes that of early scientists such as Newton and Kepler, who viewed science as a means of discovering how the universe operates, not as a tool to exclude the possibility of divine action.

Beyond physics and chemistry, the shroud also holds profound historical significance.

Art historians have long noted that the facial features seen on the shroud closely match the earliest known depictions of Christ in Byzantine iconography, dating back to the sixth century.

These images established a visual template—long hair parted in the middle, prominent nose, beard, and solemn gaze—that has persisted in Christian art for nearly fifteen centuries.

Rucker and others argue that this continuity suggests artists were copying an existing image rather than inventing one.

Today, the Shroud of Turin is preserved in a sealed, argon-filled case within the Cathedral of St.John the Baptist in Turin, Italy.

Exposure to light and oxygen is minimized to prevent further degradation of the linen.

While public exhibitions are rare, high-resolution photographs continue to provide researchers with valuable data.

Ultimately, Bob Rucker’s work challenges both skeptics and believers to reconsider the shroud not as a relic easily dismissed or blindly accepted, but as a complex physical object that resists simple explanations.

By applying nuclear science to an ancient mystery, he has reframed the discussion in unexpected ways, suggesting that the cloth’s anomalies may point to an extraordinary event rather than human artifice.

Whether one accepts his conclusions or not, Rucker’s research underscores a broader principle: genuine scientific inquiry requires humility.

It demands a willingness to follow evidence wherever it leads, even when that path crosses the boundaries of current knowledge.

In the case of the Shroud of Turin, that path continues to challenge assumptions about history, science, and the nature of reality itself.

News

Scientists Just Reviewed Grok 4’s Buga Sphere Model, Then They Noticed This…

The Buga Sphere: A Mysterious Object, Extraordinary Claims, and the Questions Challenging Modern Science In early March 2025, an event…

What Scientists Just Discovered Beneath Jesus’ Tomb in Jerusalem Will Leave You Speechless Did Archaeologists Uncover a Hidden Secret Beneath One of the Holiest Sites on Earth? Deep beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, scientists have made a discovery that few people are talking about — ancient layers, unexpected structures, and evidence that could reshape what we know about Jesus’ burial site. Why was this hidden for centuries, and what does it reveal about the final days of Christ? The findings are raising serious questions among historians and believers alike — click the article link in the comments to uncover what was found.

Beneath Jerusalem’s Sacred Stone: What Scientists Discovered Under Jesus’ Tomb and Why It Matters For centuries, the Church of the…

New EVIDENCE: Head Cloth of Jesus FOUND? The Sudarium of Oviedo

The Sudarium of Oviedo, the Shroud of Turin, and the Challenge to Medieval Dating Among the most debated artifacts in…

Pope Francis: “Ethiopian Bible Proves We’ve Been Misled About Christianity and I Brought Proof” What If One of the Oldest Bibles on Earth Changes Everything We Thought We Knew About Christianity? Hidden for centuries, the Ethiopian Bible contains ancient books, forgotten teachings, and shocking differences that challenge mainstream Christian history. Why was this version ignored for so long, and what does it reveal that the modern Bible doesn’t? The answer may reshape faith, history, and belief itself — click the article link in the comments to uncover the truth.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Ancient Bible That Challenges Common Assumptions About Christianity The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church stands…

When Jesus’ TOMB Was Opened For The FIRST Time, This is What They Found

The Unveiling of Jesus Christ’s Tomb: History, Discovery, and Impact The tomb of Jesus Christ has long stood as one…

What AI Just Found in the Shroud of Turin — Scientists Left Speechless

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has remained an enigma that fascinates both believers and scientists. This fourteen-foot-long linen cloth,…

End of content

No more pages to load