For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has occupied a unique and uneasy space between faith and science.

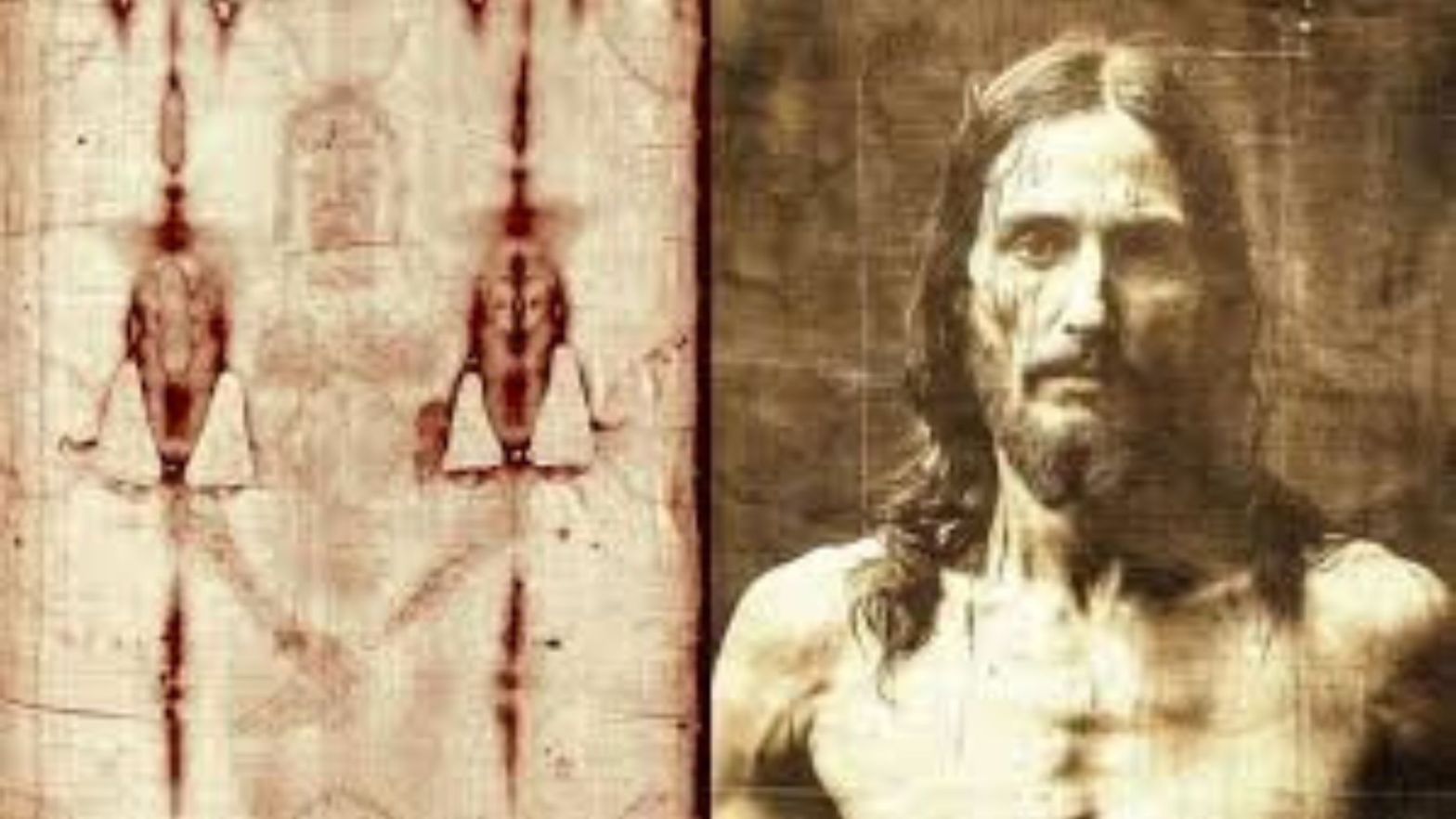

Preserved in a climate-controlled chapel in Turin, Italy, this long strip of ancient linen bears the faint image of a crucified man—front and back—etched into the fabric in a way no one has fully explained.

To believers, it may be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ.

To skeptics, it is one of history’s most sophisticated religious artifacts.

To scientists, it is an enduring puzzle that resists simple answers.

Now, with artificial intelligence entering the conversation, the debate has taken on a new and unexpected dimension—one that excites curiosity but also raises profound concern among Christians worldwide.

At first glance, the Shroud appears unremarkable: a yellowed linen cloth measuring roughly 14 feet long and just over 3 feet wide.

Yet closer inspection reveals an image unlike any other known object.

The figure appears to have suffered wounds consistent with Roman crucifixion—scourge marks across the back, puncture wounds on the scalp resembling a crown of thorns, nail injuries to the wrists and feet, and a deep wound in the side consistent with a spear.

These marks correspond closely with Gospel descriptions of Jesus’ execution.

Even more striking is the nature of the image itself.

It is not painted, dyed, or woven into the fabric.

Instead, it exists as a superficial discoloration of the linen fibers, visible more clearly in photographic negative than to the naked eye.

When analyzed, the image also contains three-dimensional information, a property no known medieval artwork naturally produces.

The Shroud’s documented history begins in the mid-14th century, when it was displayed in Lirey, France, by a knight named Geoffroi de Charny.

Almost immediately, its authenticity was challenged.

In 1389, a local bishop dismissed it as a forgery, claiming an artist had confessed to creating it.

Yet despite skepticism, the cloth continued to move through the hands of royalty and clergy, eventually coming into the possession of the House of Savoy.

It survived fires, wars, and centuries of handling, arriving in Turin in the late 16th century, where it remains today under the guardianship of the Catholic Church.

Notably, the Church has never officially declared it to be the burial cloth of Christ, referring to it instead as an object of veneration rather than doctrine.

Scientific scrutiny intensified in the modern era.

In 1978, an international team of researchers conducted extensive examinations, concluding there was no evidence of paint, pigment, or photographic technique.

The image appeared to be the result of an unknown process that altered only the topmost fibers of the cloth.

Then, in 1988, carbon-14 dating tests conducted by laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona appeared to settle the matter.

The samples tested dated the linen to between 1260 and 1390 CE, placing it squarely in the medieval period.

For many, this was definitive proof that the Shroud could not be from the time of Jesus.

Yet the controversy did not end there.

Critics questioned whether the sample used for carbon dating came from an original section of the cloth or from a medieval repair area, especially given the Shroud’s long history of damage and restoration.

Others raised concerns about contamination from smoke, bacteria, and centuries of human contact.

In subsequent years, reanalysis of the original data suggested inconsistencies between samples, reopening debate rather than closing it.

A major shift occurred in 2022, when researchers employed a different method known as Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering to analyze the natural aging of the linen’s cellulose structure.

Unlike carbon dating, this technique examines how flax fibers degrade over time.

The results suggested that the Shroud’s linen had aged in a manner consistent with first-century fabrics from the Middle East.

While not universally accepted, the study reignited discussion by suggesting the cloth could indeed be nearly 2,000 years old.

As scientific uncertainty persisted, the Shroud remained powerful precisely because of its ambiguity.

For Christians, it functioned not as proof, but as a silent witness—an object that invites contemplation rather than certainty.

That balance, however, was disrupted when artificial intelligence entered the narrative.

In recent years, high-resolution images of the Shroud have been processed using advanced AI image-generation tools.

By analyzing tonal variations and anatomical proportions within the faint imprint, AI systems produced highly detailed digital reconstructions of a human face—presented by some media outlets as a possible representation of Jesus.

These images quickly spread across social media, provoking fascination, emotional reactions, and deep unease.

For many viewers, the AI-generated face felt uncannily familiar: long hair, beard, solemn expression, visible signs of suffering.

Some described the image as moving, even intimate, as though technology had bridged centuries of distance.

Others were immediately skeptical, pointing out that AI systems are trained on existing images—many of which reflect centuries of Westernized depictions of Christ rather than the historical reality of a first-century Jewish man from the Middle East.

This realization exposed a critical issue.

Artificial intelligence does not discover truth; it synthesizes patterns.

Its outputs are shaped by the data it absorbs, including cultural bias, artistic tradition, and collective imagination.

As a result, the AI-generated image says as much about modern humanity as it does about the Shroud itself.

For Christian theologians and clergy, the implications go far deeper.

Many argue that the power of the Shroud lies precisely in what it does not reveal.

Its blurred image preserves mystery, inviting faith rather than satisfying curiosity.

By “clarifying” or “enhancing” the image through AI, critics fear that technology risks transforming a sacred object into a spectacle—replacing reverence with consumption.

There is also a theological concern about intention.

Sacred art has traditionally been created through prayer, contemplation, and spiritual discipline.

An algorithm, no matter how advanced, lacks consciousness, belief, or devotion.

While it can approximate form, it cannot comprehend meaning.

For some believers, allowing a machine to interpret the face of Christ feels like crossing a line between human inquiry and divine mystery.

These anxieties extend beyond imagery.

As AI becomes increasingly embedded in religious spaces—answering theological questions, composing prayers, and even assisting in worship—some Christians worry about a gradual erosion of human presence in faith communities.

Religion, they argue, is not meant to be efficient or optimized.

It is relational, embodied, and deeply human.

Faith is lived through shared silence, communal suffering, physical gathering, and personal connection—experiences that cannot be replicated by screens or code.

The Shroud of Turin, in this context, has become a symbol of a much larger tension.

It represents the boundary between what can be analyzed and what must be contemplated.

It asks whether humanity’s growing technological power enhances understanding or undermines humility.

It forces modern society to confront an uncomfortable question: just because we can visualize, simulate, and reconstruct everything, should we?

Interestingly, even among skeptics, the AI reconstructions have prompted reflection rather than dismissal.

Some argue that the images reveal less about Jesus and more about humanity’s enduring desire to see, to know, and to connect.

The Shroud’s endurance across centuries suggests that its true significance may lie not in authentication, but in its ability to provoke wonder across generations.

Today, the Shroud remains where it has always been—silent, fragile, unresolved.

It continues to draw scientists seeking explanation, believers seeking meaning, and now technologists seeking interpretation.

Artificial intelligence has not solved the mystery.

Instead, it has exposed a deeper one: how modern humanity navigates the space between knowledge and faith in an age that increasingly demands certainty.

Perhaps the enduring power of the Shroud of Turin lies precisely in its resistance to final answers.

In a world driven by clarity and speed, it insists on patience.

In an era of digital reconstruction, it preserves ambiguity.

And in the face of machines that promise revelation, it quietly reminds us that some truths are not meant to be rendered—but revered.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load