For centuries, a single piece of cloth has captured the imagination and scrutiny of the world, a linen relic that bears the faint image of a crucified man.

Scholars debated its authenticity, believers held it as proof, and skeptics dismissed it as legend.

Yet, as science advanced, a new perspective emerged, one that combined meticulous measurement with the power of artificial intelligence.

The Shroud of Turin, long shrouded in both faith and doubt, revealed layers of complexity that went beyond mere image or stain.

Hidden within its fibers lay patterns, geometry, and repetition that defied conventional explanation.

Was it an accident, a miracle, or a phenomenon that humanity was never meant to fully understand?

The Shroud itself is unassuming in form but profound in impact.

Measuring approximately fourteen feet long and just over three feet wide, the linen is woven in a herringbone twill that interacts with light like a subtle ripple.

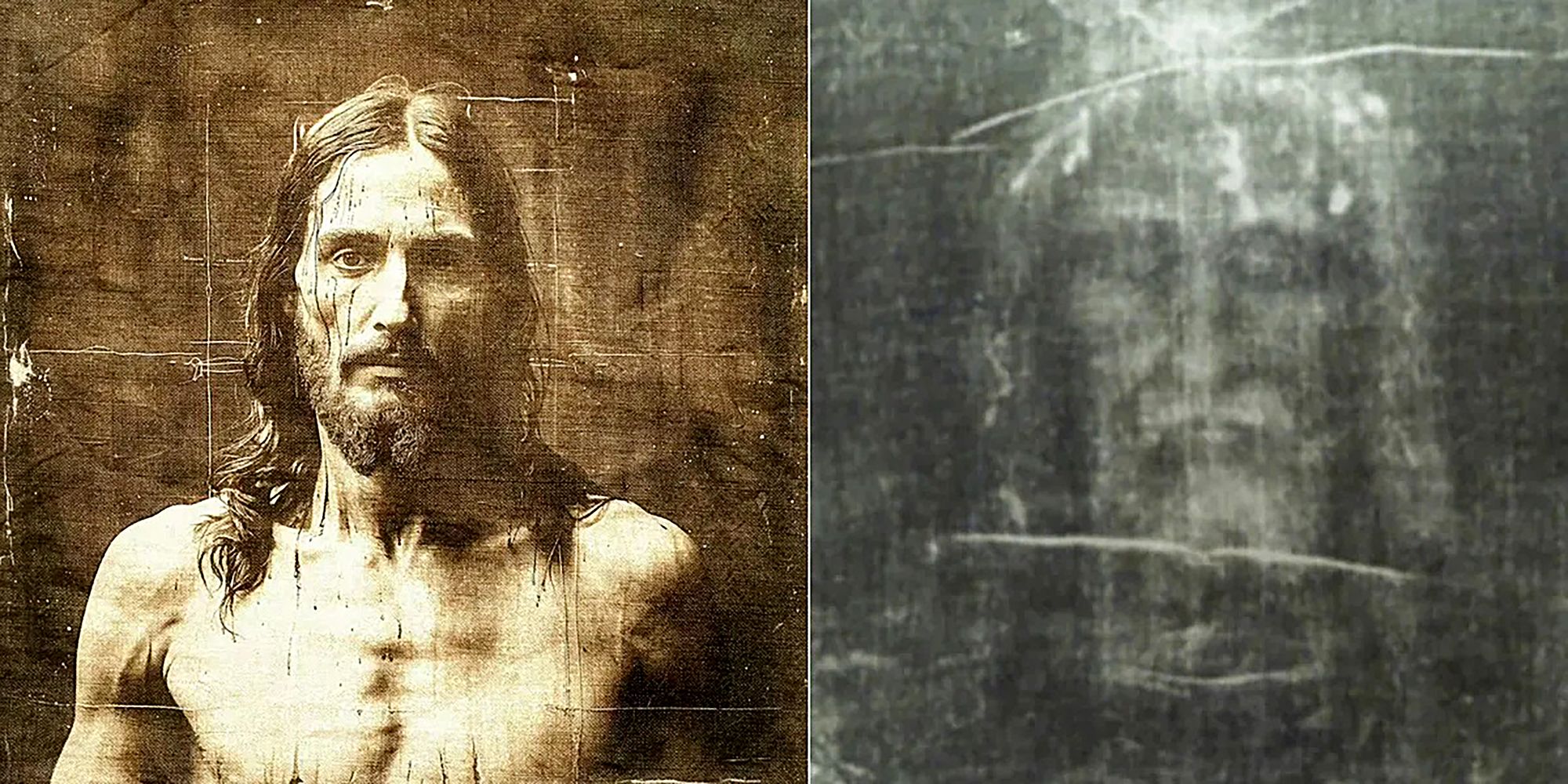

Across its surface rests the ghostly outline of a man, head to toe, front and back, as though a body had lain there briefly and vanished, leaving behind a spectral imprint.

The injuries are depicted with precise subtlety: wrist marks corresponding to where nails might have entered, a wound on the side hinting at a spear thrust, stains on the feet, faint impressions around the scalp suggesting a crown of thorns.

The face, quiet and composed, with closed eyes, parted beard, and hair that seems to float above the cloth, conveys presence without assertion.

The first documented display of the Shroud occurred in France during the 13th century, in a small town that soon became a destination for pilgrims.

From there, it changed hands several times until it arrived in Turin in 1578, where it has remained under the custody of the House of Savoy and later the Church, surviving fire, smoke, and centuries of scrutiny.

Today it is housed in a climate-controlled case within the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, shielded from the ravages of time, yet always inviting inquiry.

Photography brought the Shroud into modern consciousness in 1898.

The Italian lawyer Secondo Pia captured images of the cloth expecting a faint, muddled impression.

Instead, the photographic negative revealed a startlingly detailed face.

Features that had been barely perceptible became clear: the shape of the cheekbones, the contours of the lips, strands of hair, and hands crossed over the pelvis.

This reversal demonstrated that the image interacted with light in a manner unlike ordinary paint or pigment, shifting the debate from devotion to scientific curiosity.

Throughout the twentieth century, the Shroud underwent increasingly precise analysis.

Chemists examined individual fibers, while microscopes and forensic methods measured the interaction between the bloodlike areas and the image.

Textile historians compared the weave to known techniques from the eastern Mediterranean, and pollen studies suggested exposure to flora consistent with the Levant.

These results never provided final answers but instead fueled further investigation, each discovery raising new questions rather than closing the case.

A central mystery lies in the image’s superficiality.

Microscopic examination reveals that the discoloration affects only the outermost fibrils of the linen, without pigment, binder, or brush strokes.

Depth mapping shows a correlation between image darkness and the distance from a presumed body surface: areas closer to the imagined body appear darker, areas farther away lighter.

Attempts to reproduce this effect with heat, vapor, or chemical processes have come close but never exactly, leaving the Shroud unique in its properties.

The most famous modern test came in 1988, when radiocarbon dating from a corner of the cloth suggested a medieval origin between 1260 and 1390.

This result was widely reported as definitive, seemingly placing the Shroud firmly in the Middle Ages.

Yet the sample site was controversial.

It was taken from a corner that had undergone repair, possibly altering the composition of the fibers, and included threads of cotton intermixed with linen.

Critics argued that this small, potentially contaminated section could not conclusively date the entire artifact.

Even as methods like wide-angle X-ray scattering and further pollen analysis offered hints of greater antiquity, access limitations and the Shroud’s heterogeneous history kept certainty out of reach.

In the twenty-first century, artificial intelligence has added a new dimension to Shroud research.

AI does not date textiles or determine authenticity, but it excels at finding subtle structure in complex data.

By analyzing high-resolution photographs, including multispectral images capturing ultraviolet and infrared responses, machine learning can detect faint patterns invisible to the human eye.

When these algorithms were applied to the Shroud, they uncovered persistent geometric structures, repeating ratios, and symmetries that did not correspond to folds, lighting artifacts, or random noise.

The results suggested a level of order in the image that had not been appreciated before.

Prior to AI analysis, 3D simulations had already raised questions about image formation.

If the Shroud had been created by direct contact with a human body, distortions would appear along areas such as the shoulders, cheeks, and fingers, as the cloth draped over a three-dimensional form.

Yet the proportions of the Shroud’s image do not align with a simple contact map.

The correlation between image darkness and distance appears consistent across the body, indicating that the formation process involved a form of depth mapping rather than straightforward pressure or pigment application.

The AI studies revealed that the intensity of the image obeyed rules reminiscent of mathematical surfaces rather than artistic brushwork.

The discoloration sits only on the crowns of fibers, and edges are soft and continuous across thread boundaries.

Experiments with lasers and controlled chemical reactions have struggled to replicate such a precise and superficial effect without causing damage.

Further, the symmetry in the face and torso persists across different wavelengths and imaging methods, suggesting that it is an intrinsic property of the image rather than a visual illusion or artifact of photography.

The Shroud’s bloodlike stains appear to be independent of this geometric order, implying that multiple processes may have been involved.

One layer of the fabric may record one type of event while another preserves a distinct phenomenon.

Theories have ranged from corona discharges and ultraviolet radiation bursts to electrostatic effects, yet none fully account for the combination of shallow penetration, gradient mapping, and long-term stability.

Some researchers propose that the image may represent an unprecedented form of physical or chemical event, one that has no analogue in known history.

The implications extend beyond science into philosophy and theology.

While believers may see the patterns as evidence of miraculous intervention, scientists recognize the uniqueness of the phenomenon without resorting to divine explanations.

The Shroud resists categorization, challenging both religious and secular assumptions.

It exemplifies a rare case where careful measurement and curiosity take precedence over immediate judgment, inviting continued study in physics, chemistry, information theory, and material science.

One striking insight from AI is the notion that the Shroud behaves like a signal, a dataset preserving faint but coherent information across its surface.

Compression analyses, frequency transforms, and principal component methods reveal that the image’s geometry is robust, recurring across multiple scales and resistant to randomization.

This has led some researchers to describe it as a “spatial intelligence in degradation,” or a “decaying signal” that encodes structure even after centuries of handling, exposure, and damage.

The Shroud’s story is also a lesson in the interplay between access and evidence.

Conservators limit direct sampling to protect the relic, meaning that most tests rely on small, potentially non-representative sections.

Each thread carries weight, and any small variation can dominate the conclusions drawn.

This tension between scientific rigor and preservation underscores the care required in interpreting results.

Future investigations might involve non-invasive mapping, microscopic imaging, or computational modeling to expand knowledge without harming the artifact.

Ultimately, the Shroud teaches humility.

It demonstrates that some phenomena do not yield their secrets easily, that uniqueness is not proof of miracle, nor is anomaly evidence of forgery.

It challenges researchers to focus on mechanisms rather than origins, on the processes that can generate the observed order rather than the identities of those who created it.

AI contributes to this endeavor by highlighting patterns, suggesting priorities for study, and clarifying where experiments could provide meaningful insight.

Questions abound.

Does the geometric order persist across the entire cloth or only in certain regions? Do faint structures exist in other relics, or is the Shroud truly singular? What physical or chemical processes could create such precise superficiality and depth mapping? Can a combination of microscopy, spectroscopy, and computational modeling identify the mechanism responsible? Each question invites meticulous, patient investigation, rewarding curiosity and careful reasoning rather than premature conclusion.

The Shroud of Turin has endured as relic, icon, artifact, and mystery.

Its fibers hold a story that refuses to be reduced to simple categories.

It has survived fire, flood, and centuries of human interpretation.

In the age of artificial intelligence, it presents a new challenge: to quantify the subtle, hidden order that has eluded human observation for centuries.

It offers a unique lesson in the value of questions over answers, in the humility required to engage with the unknown, and in the beauty of a phenomenon that continues to inspire wonder.

Whether artifact, phenomenon, or unique signal, the Shroud remains a canvas of possibility, inviting new generations of scientists, engineers, and scholars to explore the boundaries of knowledge, to measure carefully, and to embrace the extraordinary patience that such a puzzle demands.

In the end, the Shroud may resist final explanation, but it does so with purpose, compelling humanity to refine its tools, broaden its questions, and respect both mystery and evidence.

Its order is a challenge, not a solution; a map, not a destination.

To study it is to accept that some phenomena speak in subtle languages, that some truths must be coaxed from data rather than assumed, and that in doing so, science and wonder coexist in a dialogue that has spanned centuries.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load