Even though the Moon lies only about two hundred forty thousand miles from Earth, it remains surprisingly difficult to observe in fine detail using ground based telescopes.

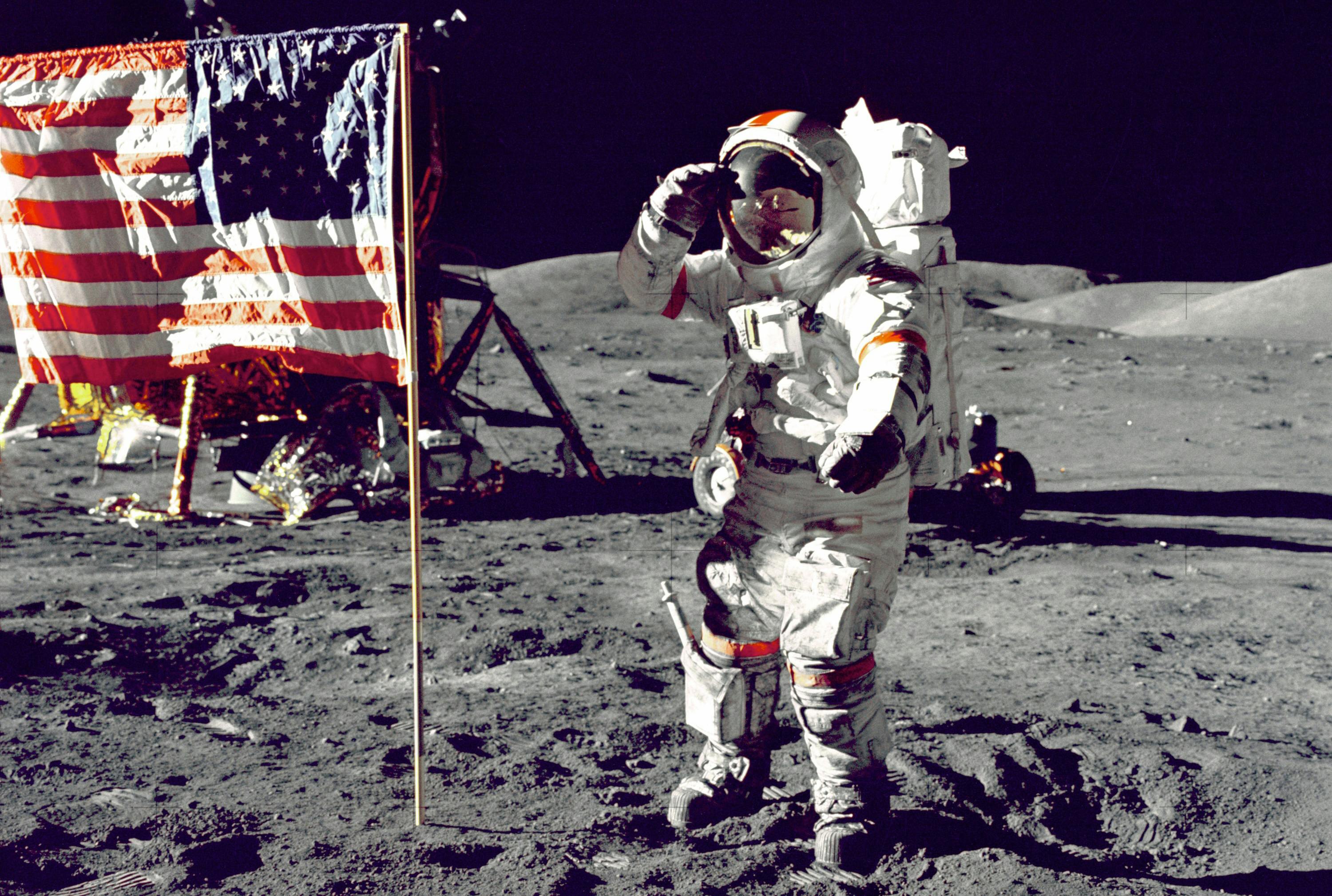

This challenge becomes especially striking when scientists attempt to image the Apollo 11 landing site, one of the most historically significant locations in human history.

Despite decades of technological progress, even the most powerful Earth based observatories cannot clearly reveal the small objects left behind by the first humans to walk on another world.

This limitation has forced scientists to confront the physical boundaries of observation and to reassess what can realistically be seen from Earth.

At first glance, the distance to the Moon seems manageable.

In cosmic terms, it is extremely close.

Yet astronomy is governed not by distance alone, but by angular resolution, atmospheric conditions, and the fundamental laws of optics.

The objects left at the Apollo 11 landing site are simply too small to be resolved from Earth.

The lunar module descent stage, for example, measures only a few meters across.

From Earth, this translates into an angular size far below the resolving power of even the largest optical telescopes.

The Moon itself occupies just over half a degree of the sky.

Within that narrow disk, distinguishing objects that are only a few meters wide is an extraordinary challenge.

Even if a telescope had perfect optics, Earth’s atmosphere introduces constant distortion.

Turbulence caused by temperature differences, wind, and variations in air density bends incoming light in unpredictable ways.

This effect, known as atmospheric seeing, blurs fine details and limits resolution.

Large lunar features such as craters, mountain ranges, and dark volcanic plains are easily visible from Earth.

However, human made objects on the Moon shrink into invisibility.

The Apollo landing sites appear no different from the surrounding terrain when viewed through ground based telescopes.

This reality has disappointed many observers who hoped modern technology would provide definitive visual confirmation of humanity’s first lunar footsteps.

Astronomers have long attempted to overcome these limitations.

One commonly used method is image stacking, which involves combining hundreds or even thousands of individual frames.

By selecting the sharpest moments when atmospheric turbulence briefly subsides, scientists can produce images with improved clarity.

While stacking enhances contrast and reduces noise, it cannot overcome the fundamental resolution limit imposed by the atmosphere and telescope aperture.

Adaptive optics represents another major advancement.

This technology measures atmospheric distortion in real time and adjusts telescope mirrors accordingly.

Some ground based observatories equipped with adaptive optics can rival or even surpass the image quality of space telescopes for certain targets.

However, even with these corrections, the smallest lunar artifacts remain far beyond reach.

The physical size of the Apollo equipment is still too small to resolve.

Interferometry pushes the limits further by linking multiple telescopes to simulate a much larger aperture.

This technique can improve angular resolution dramatically.

In ideal conditions, interferometric systems can resolve lunar features several hundred feet across.

Yet the Apollo hardware, measuring only a few meters, remains smaller than a single pixel even in these advanced systems.

As a result, the equipment cannot be visually distinguished.

The Moon’s tidal locking provides one advantage.

All Apollo landing sites face Earth, meaning they are always visible from our planet.

This orientation eliminates the need to wait for favorable lunar rotation.

Despite this constant visibility, clear images of the landing sites remain elusive.

The challenge is not one of alignment, but of physics.

These observational limits have occasionally fueled misunderstandings and unnecessary skepticism.

Some have questioned why Earth based telescopes cannot clearly show the Apollo landing sites.

The answer lies not in doubt, but in optical reality.

Without leaving Earth orbit, there is a hard ceiling on achievable resolution.

The inability to see Apollo artifacts directly is a reminder that technological power does not override physical law.

Amateur astronomers have also pushed their equipment to remarkable extremes.

Using high quality telescopes, specialized cameras, and advanced processing software, some have captured lunar images revealing craters less than a mile across.

Regions near the Sea of Tranquility, where Apollo 11 landed, can be imaged with impressive detail.

Nearby craters named after Apollo astronauts are identifiable, offering a tangible connection between human history and lunar geography.

Despite these achievements, the actual landing site remains smaller than a single pixel in amateur images.

Identifying it relies on surrounding landmarks rather than direct visibility.

Observers carefully time their sessions to coincide with favorable lighting near lunar sunrise or sunset, when long shadows enhance surface relief.

Observing when the Moon is high in the sky also reduces atmospheric interference.

Professional observatories benefit from far larger instruments and more stable observing conditions.

Adaptive optics systems at major facilities significantly sharpen lunar images.

Interferometric arrays extend resolving power even further.

Still, these observatories face the same fundamental constraints.

They can study large scale geology and surface variations, but not small human made objects.

Space based telescopes might seem like the ideal solution.

Orbiting above Earth’s atmosphere, they avoid atmospheric distortion entirely.

However, space telescopes such as the Hubble Space Telescope were designed primarily for deep space observation.

Their pixel scale is optimized for distant galaxies, not close planetary surfaces.

When pointed at the Moon, each pixel covers hundreds of feet of terrain.

The Apollo landing hardware occupies only a tiny fraction of a single pixel.

To resolve the lunar module from Earth orbit, a space telescope would require a mirror hundreds of feet across.

Such a structure remains far beyond current engineering capabilities.

Although some ground based systems rival space telescopes in effective aperture through interferometry, they still cannot overcome the combined challenges of resolution and atmospheric interference.

The true breakthrough came with lunar orbiters.

By placing cameras in orbit around the Moon, scientists eliminated atmospheric distortion and drastically reduced viewing distance.

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, launched in 2009, carries high resolution cameras capable of imaging the surface at scales of about half a foot per pixel.

At this resolution, Apollo artifacts become clearly visible.

Orbital images reveal the lunar module descent stages, scientific instruments, rover tracks, and even astronaut footpaths.

Repeated imaging under different lighting conditions allows scientists to study shadows and subtle surface features.

These images provide definitive confirmation of the Apollo missions and preserve a detailed visual record of humanity’s first steps beyond Earth.

However, these observations also revealed something unexpected.

Over time, the Apollo sites have shown subtle changes.

Footprints appear less distinct, tracks soften, and contrast diminishes.

The Moon, once thought to be static and unchanging, is subject to slow but continuous alteration.

Micrometeorite impacts, solar radiation, and electrostatic dust movement gradually modify the surface.

This realization unsettled many researchers.

The Apollo sites were often imagined as perfectly preserved time capsules.

Instead, they are slowly blending back into the lunar regolith.

While the changes occur over decades, not years, they raise concerns about long term preservation.

Without careful stewardship, physical traces of humanity’s earliest lunar exploration could fade significantly.

The discovery prompted discussions about protecting lunar heritage sites.

Future missions must consider the impact of landings, engine exhaust, and surface operations.

Even orbital passes can contribute to disturbance over time.

Preservation has become a priority not only for historical reasons, but also for scientific documentation.

Looking ahead, future lunar missions promise even greater observational capability.

Next generation orbiters and landers will carry more advanced imaging systems.

Artificial intelligence and improved data processing will allow scientists to detect subtle environmental changes.

These tools will help monitor the condition of historic sites while informing future exploration.

International cooperation is also shaping the future of lunar observation.

Space agencies around the world are working toward shared standards for exploration and preservation.

There is growing interest in recognizing Apollo landing sites as cultural landmarks deserving protection.

Public engagement plays a role as well.

High resolution maps, virtual reconstructions, and open access data allow people worldwide to explore the Moon without physically disturbing sensitive areas.

These tools help balance curiosity with conservation.

Ultimately, the difficulty of seeing the Apollo 11 landing site from Earth is not a failure of technology, but a lesson in humility.

It highlights the limits of observation and the importance of perspective.

Only by leaving Earth and approaching the Moon directly could humanity truly see what it left behind.

The Moon remains both a scientific frontier and a mirror reflecting human ambition, ingenuity, and responsibility.

News

JRE: “Scientists Found a 2000 Year Old Letter from Jesus, Its Message Shocked Everyone”

There’s going to be a certain percentage of people right now that have their hackles up because someone might be…

If Only They Know Why The Baby Was Taken By The Mermaid

Long ago, in a peaceful region where land and water shaped the fate of all living beings, the village of…

If Only They Knew Why The Dog Kept Barking At The Coffin

Mingo was a quiet rural town known for its simple beauty and close community ties. Mud brick houses stood in…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Nearly three decades after the death of hip hop icon Tupac Shakur, investigators searching a residential property connected to the…

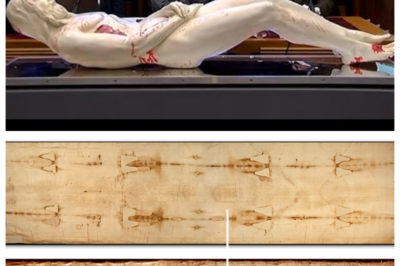

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early 2018 a group of researchers in Rome presented a striking three dimensional carbon based replica that aimed to…

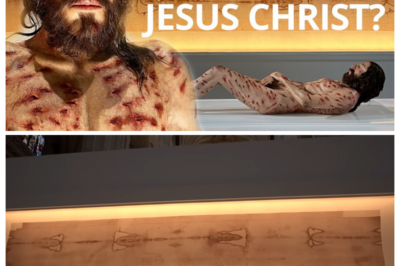

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

**The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca** For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load