The Shroud of Turin: DNA, Dust, and the Mystery Science Cannot Close

Few artifacts in human history have inspired as much fascination, devotion, and controversy as the Shroud of Turin.

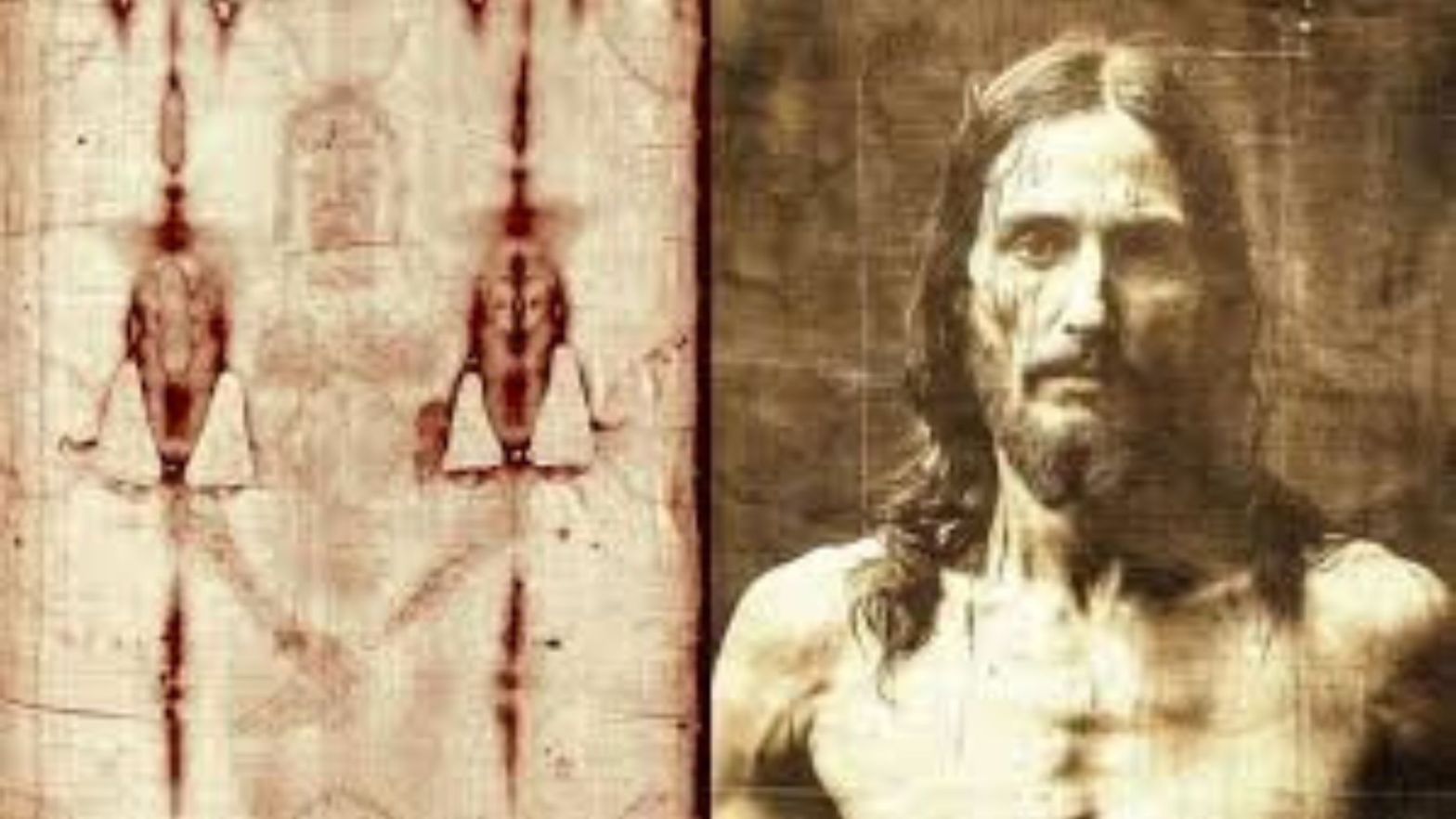

At first glance, it is nothing more than an ancient linen cloth bearing the faint image of a crucified man.

Yet for more than a century, scientists, historians, theologians, and skeptics have examined it with growing intensity.

What they have found has not resolved the debate.

Instead, it has deepened it.

For millions of believers, the shroud is the burial cloth of Jesus Christ.

For critics, it is an extraordinarily clever medieval forgery.

Between these positions lies one of the most complex forensic puzzles ever investigated.

In recent decades, advances in genetics, microscopy, spectroscopy, and imaging have transformed the shroud from a religious icon into an object of scientific scrutiny.

The results have been both surprising and unsettling.

A Photograph That Changed History

Modern scientific interest in the Shroud of Turin began on May 28, 1898.

During a public exhibition in Turin, an Italian lawyer and amateur photographer, Secondo Pia, was granted permission to photograph the relic.

Using large glass plates and intense magnesium lighting, Pia captured two images of the cloth late at night inside the cathedral.

When he developed the plates in his darkroom, he was stunned.

The photographic negative revealed not a distorted inversion of the image, as would be expected from a painting or drawing, but a strikingly lifelike positive image of a man’s face and body.

Details such as a broken nose, swollen cheek, beard, and closed eyes appeared with unexpected clarity.

This discovery marked a turning point.

The image on the shroud appeared to function as a photographic negative centuries before photography was invented.

While skeptics argued that artistic techniques could potentially explain the effect, no definitive method has ever been demonstrated that reproduces the shroud’s unique characteristics.

An Image Unlike Any Other

Subsequent analyses revealed additional anomalies.

The image contains three-dimensional information, meaning its intensity correlates with the distance between the cloth and the body it covered.

When processed by modern image analyzers, the shroud behaves more like encoded spatial data than pigment on fabric.

Microscopic examinations found no evidence of paint, brush strokes, or binding media commonly used by medieval artists.

The image is confined to the topmost fibers of the linen, penetrating no deeper than a fraction of a millimeter.

These properties remain unexplained by conventional artistic or chemical processes.

As a result, researchers began to shift focus away from how the image was formed and toward what else the cloth might contain.

DNA in the Fibers

In 2015, a multidisciplinary team of geneticists and biologists associated with the University of Padua published a study in Scientific Reports, a journal within the Nature portfolio.

Their goal was not to identify the DNA of a single individual, but to examine the biological traces embedded in the linen fibers.

Using sterile micro-vacuum devices and archival dust samples collected during earlier restorations, the researchers extracted microscopic biological material from deep within the weave of the cloth.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques were applied, focusing primarily on mitochondrial DNA, which is more abundant and more resilient than nuclear DNA.

The results were unexpected.

Instead of a single dominant genetic profile, the samples revealed mitochondrial DNA from multiple human populations spanning Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia.

A Cloth That Traveled

The presence of European DNA was not surprising.

The shroud has been documented in Europe since the mid-14th century and has been handled by clergy, royalty, restorers, and countless pilgrims.

More intriguing were genetic markers associated with Middle Eastern populations, including haplogroups commonly found in historically isolated communities of the Levant.

These findings were consistent with an origin or prolonged presence in that region, though they did not constitute proof of identity.

The study also detected traces associated with North and East Africa, South Asia, and East Asia.

Haplogroups linked to the Indian subcontinent and China appeared in small but measurable quantities.

Critics emphasized that contamination over centuries could account for such diversity, while proponents argued that the geographic breadth was difficult to reconcile with a purely medieval European origin.

When researchers mapped the genetic data against known historical trade and pilgrimage routes, a pattern emerged that aligned with ancient accounts describing the movement of a relic known as the Mandylion.

According to Byzantine sources, this cloth was displayed folded so that only the face was visible and was venerated in Edessa (modern Şanlıurfa, Turkey), a major crossroads on the Silk Road.

Pollen as Geographic Evidence

Biological clues were not limited to human DNA.

Palynology, the study of pollen, provided another layer of evidence.

Independent examinations by Israeli botanist Avinoam Danin and Swiss criminologist Max Frei identified pollen grains trapped within the linen.

Among dozens of plant species identified, many were native to Europe, as expected.

However, a significant number originated in the Middle East and Anatolia.

Particularly notable were pollen grains from plants that grow exclusively in a narrow region between Jerusalem and Jericho.

One species, Gundelia tournefortii, a thorny desert plant, appeared in unusually high concentrations, especially around the head area of the cloth.

This plant blooms in early spring and has been proposed by some researchers as a plausible candidate for the “crown of thorns” described in the Christian Gospels.

While this interpretation remains debated, the geographic specificity of the pollen is widely acknowledged.

Blood, Trauma, and Biochemistry

For decades, skeptics argued that the reddish stains on the shroud were painted pigments.

In recent years, advanced analytical techniques challenged that claim.

Studies using Raman spectroscopy and transmission electron microscopy identified the presence of human blood components, including hemoglobin.

Researchers also detected nanoparticles containing ferritin and creatinine bound to hemoglobin.

According to medical experts involved in the studies, such concentrations are consistent with severe trauma, extreme physiological stress, and dehydration.

These biochemical markers are associated with conditions such as rhabdomyolysis and hypovolemic shock.

The blood type identified in several studies was AB, a relatively rare group.

While blood typing on ancient material is inherently controversial, similar findings have been reported on other relics traditionally associated with early Christianity.

Another anomaly concerned the color of the blood stains.

Ancient blood typically darkens over time, yet the stains on the shroud remain reddish.

Elevated levels of bilirubin, a compound released during intense physical trauma, were proposed as a contributing factor.

This explanation remains debated but has not been conclusively disproven.

The Limits of Explanation

Despite more than a century of investigation, no single theory has successfully accounted for all observed properties of the shroud.

Medieval forgery hypotheses struggle to explain the image’s physical and chemical characteristics, the absence of pigments, and the presence of geographically specific pollen.

Conversely, claims of supernatural origin fall outside the scope of empirical science.

Radiocarbon dating conducted in 1988 placed the cloth in the medieval period, but the results have been heavily criticized due to sampling location, possible contamination, and statistical handling.

Subsequent studies have suggested that the tested samples may not have been representative of the entire cloth.

Today, most researchers agree on one point: the Shroud of Turin cannot be understood through a single discipline.

It exists at the intersection of chemistry, physics, biology, history, and theology.

An Open Case

Modern scientists increasingly describe the shroud not as a solved problem, but as an open forensic case.

Each new method reveals additional layers of complexity.

Rather than confirming or disproving belief, the evidence has challenged assumptions on both sides of the debate.

Whether viewed as a sacred relic or a historical enigma, the Shroud of Turin continues to resist definitive explanation.

Its fibers preserve not only an image, but a record of human contact spanning continents and centuries.

In that sense, the shroud functions less as an answer and more as a question—one that science has not yet learned how to close.

News

Girl In Torn Clothes Went To The Bank To Check Account, Manager Laughed Until He Saw The Balance What If Appearances Lied So Completely That One Look Cost Someone Their Dignity—and Another Person Their Job? What began as quiet ridicule quickly turned into stunned silence when a single number appeared on the screen, forcing everyone in the room to confront their assumptions. Click the article link in the comment to see what happened next.

Some people only respect you when they think you’re rich. And that right there is the sickness. This story will…

Billionaire Goes Undercover In His Own Restaurant, Then A Waitress Slips Him A Note That Shocked Him

Jason Okapor stood by the tall glass window of his penthouse, looking down at Logos. The city was alive as…

Billionaire Heiress Took A Homeless Man To Her Ex-Fiancé’s Wedding, What He Did Shocked Everyone

Her ex invited her to his wedding to humiliate her. So, she showed up with a homeless man. Everyone laughed…

Bride Was Abandoned At The Alter Until A Poor Church Beggar Proposed To Her

Ruth Aoy stood behind the big wooden doors of New Hope Baptist Church, holding her bouquet so tight her fingers…

R. Kelly Victim Who Survived Abuse as Teen Breaks Her Silence

The early 2000s marked a defining moment in popular culture, media, and public conversation around fame, power, and accountability. One…

Las Vegas Bio Lab Sparks Information Sharing, Federal Oversight Concerns: ‘I’m Disappointed’

New questions are emerging over why a suspected illegal biolab operating from a residential home in the East Valley appeared…

End of content

No more pages to load