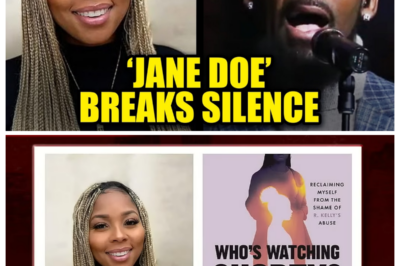

An image like no other, inspiring decades of research and debate.

The Shroud of Turin, that’s a piece of history, and it has an ongoing puzzle for science.

The Shroud of Turin is a burial cloth that’s imprinted with what many believe is the actual image of Jesus after his crucifixion.

Now, it’s been debated for years, but the shroud is back in the headlines in a major way.

Hidden deep within the ancient threads of the Turin Shroud, scientists made a discovery that stunned them.

Traces [music] of DNA.

But when the results came back, [music] the research team was left in complete disbelief.

For millions of believers around the world, the [music] shroud is believed to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, the only physical [music] remnant tied to the resurrection.

A silent witness to an event [music] that changed history.

Some even call it a fifth gospel, not written with ink or words, but with blood and suffering.

Before we go any further, we’d like to ask for your support.

If you’re finding this story meaningful, a like and a subscription [music] are the simplest ways to help us continue.

Your support truly matters to us.

Yet for skeptics, the Turin Shroud tells a very different story.

One that challenges faith, tradition, [music] and everything we think we know about the past.

To skeptics, the Turin Shroud is seen as the most elaborate and convincing medieval forgery ever produced.

Some believe it may have been created by Leonardo da Vinci himself.

Others argue it was the work of an unknown master carefully designed to [music] deceive pilgrims who longed for miracles.

For more than six centuries, this argument has never stopped.

[music] Faith stood firmly on one side, logic on the other, and neither was willing to surrender.

But in the 21st century, the age of philosophy and speculation finally gave way to something else.

Science stepped [music] in.

Cold, exact, and unforgiving.

Genetics, high energy physics, spectroscopy, forensic analysis.

Technologies emerged that made questions answerable in ways once thought impossible.

Researchers no longer treated the shroud as a holy relic.

They approached it like a crime scene, like evidence from an unsolved mystery, like a biological data vault quietly preserving 2,000 years of history.

DNA was carefully extracted and sequenced from its fibers.

Every thread was scanned with X-rays.

Blood stains were broken down to their smallest components, molecules, atoms, [music] and elemental fingerprints.

Scientists expected straightforward results, traces [music] of a single individual, or perhaps residue left behind by a medieval artist’s pigments.

Instead, what they uncovered was anything but simple.

Genetic [music] specialists at the University of Padua along with physicists working inside the sealed laboratories of ENEA encountered findings so unexpected [music] that even the most seasoned experts were left deeply unsettled.

The [music] evidence didn’t just challenge existing theories, it destroyed them.

Both skeptical explanations and traditional religious interpretations crumbled under the weight of the data.

The shroud could no longer be dismissed as mere cloth.

It became something else entirely.

A map.

A map that traces a journey beginning 2,000 years ago.

A record of suffering so detailed and exact that no known method has ever been able to recreate it.

And proof of a powerful burst of energy.

One whose true nature [music] still lies beyond the reach of modern physics.

This moment marked the start of the most comprehensive forensic investigation ever [music] conducted.

We will follow clues invisible to the naked eye, microscopic pollen grains, molecular traces, biological signatures.

Step by step, [music] we will search for whose blood truly saturated these fibers and why the evidence seems to cry out in agony, not through words, but through the language of biochemistry.

We will also explore [music] the physics behind the image itself.

an image that behaves like a photographic negative, a hologram, and [music] an X-ray all at the same time.

And finally, we will confront [music] a single question, one that left the scientific world stunned.

DNA analysis eventually forced researchers to confront a stunning conclusion.

This artifact could not have been created in Europe, and it appears to bear witness to events that [music] reshaped human history itself.

To grasp just how shocking these genetic findings are, we must go back to the very beginning of scientific research on the shroud, [music] what is now known as modern synindenology.

We must return to the moment when humanity first truly saw the face hidden within the shadows of the linen.

That moment came on May 28th, 1898 [music] in the city of Turin.

A lawyer, city councilman, and passionate amateur photographer named Sakondo Pierre was granted rare permission by King Alberto I to photograph the relic during a public exhibition held in celebration of the prince’s [music] wedding.

At the time, photography was anything but simple.

It was slow, technical, [music] and unforgiving.

Pia carried a camera nearly the size of a suitcase onto [music] tall scaffolding inside the cathedral.

To illuminate the dark interior, he relied on intense magnesium flashes and powerful [music] lamps.

He exposed two large glass plates, each measuring 50x 60 cm.

Late that night, alone in his home dark room, lit only by the dim glow of a red safety lamp, Pia carefully lowered one of the plates into a tray of developing chemicals.

And then [music] it happened.

As the image slowly appeared on the glass, Pier nearly dropped the priceless negative in disbelief, what emerged before his eyes felt unreal, almost otherworldly.

On the photographic negative, where light should become dark and dark should become light, something extraordinary appeared.

Instead of the faint blurry discoloration visible on the cloth itself, a sharp high contrast image emerged, filled with astonishing detail.

[music] A face, deep set eyes gently closed, a broken nose, a mustache and a forked beard, bruising along the right cheek.

For the first time, the figure hidden within the linen was no longer a vague shadow.

It was clearly [music] a man.

The expression on the face was striking, calm, dignified, almost commanding, and yet [music] it belonged to someone who had clearly endured extreme and unimaginable physical [music] suffering.

The effect was overwhelming.

This wasn’t just a surprise.

It was a turning point.

It completely transformed how the shroud was understood.

[music] Any normal image, whether drawn with paint, charcoal, or even blood, behaves in a predictable way when converted into a photographic negative.

Light areas turn dark.

Dark areas turn light.

The result [music] is distorted and unnatural, leaving the face flat and masklike.

But the shroud did not behave that way.

When photographed as a negative, it appeared as a true black and white photograph of a real human being.

That single fact changed [music] everything.

And even today, it remains impossible to dismiss, no matter how skeptical or determined to [music] disprove it someone may be.

What the naked eye sees on the cloth is not a normal image at all.

It is already a negative.

And that raises a question that should not exist yet does.

Who in the Middle Ages, whether [music] in the 10th or 11th century, understood the principles of photography? Who knew that light could be reversed to reveal a hidden image? The answer is simple.

No one.

Who could intentionally create a flawless negative image without any way to see, test, or confirm the result? Photography would not be invented for another 800 years.

The human eye and brain are not biologically capable of viewing the world in negative, let alone reproducing it with such [music] precise control over light and shadow.

This was the first real mystery, [music] the first fracture in what had seemed like an unbreakable wall of skepticism.

The shroud [music] did not behave like a painting.

It behaved like a photographic plate, [music] capturing a single instant in time.

Over the decades, the cloth has been examined using X-rays, [music] ultraviolet light, infrared imaging, and laser scanning.

Yet, its [music] greatest secret was never hidden in the image itself.

It was in the dirt, in the dust, in the microscopic particles trapped between the linen fibers over 2,000 years of handling, movement, [music] and exposure.

In 2015, a team of geneticists and biologists led by Professor Johnny Barkachi at the University of Padua was granted [music] unprecedented access to the relic.

Their mission was as daring as it was unsettling, [music] to locate and analyze DNA.

They were not searching for the DNA of God.

Science has no clear model for what such a trace should look like.

There is no reference sample, no established standard for comparison.

The researchers were not trying to identify a single person.

Their goal was far broader.

To reconstruct the life story of the cloth itself, where it had traveled, who had touched [music] it, and whose hands had held it across the centuries.

To do this, they used specially designed sterile micro vacuum devices [music] equipped with ultrafine filters.

These tools gently collected microscopic dust, pollen, and organic fragments, not only from the surface of the fabric, but from the deep spaces between the warp and weft [music] threads, where ancient material can remain sealed for thousands of years.

They also examined particles collected during the 1988 restoration, samples that had been carefully preserved in archival storage.

This work pushed science to its limits.

Even [music] the tiniest modern contamination, a breath, a sneeze, a single flake of skin from a priest, conservator, or technician, could wipe out ancient signals and replace them with modern genetic noise.

The samples were transported to an ultra clean controlled laboratory.

There, [music] sequencing began using next generation sequencing known as NGS.

The scientists [music] focused on mitochondrial DNA from both plants and humans and for a critical reason.

Unlike nuclear DNA, mitochondrial DNA exists in hundreds of copies per cell.

It is passed down exclusively through the maternal line and survives far longer in ancient material.

Because of this, it serves as a powerful and reliable marker of geographic origin, population movement, and human migration.

For weeks, [music] computers ran non-stop, decoding millions of nucleotide sequences and comparing them against global genomic databases [music] representing populations from around the world.

When the final diagrams appeared on the screens, [music] maps of genetic haplo groups and ancestral lineages, the researchers understood they were facing something that defied [music] any simple explanation and certainly any ordinary forgery.

This was not the genetic signature of a single individual.

It was something far more complex.

It was a genetic portrait of humanity itself.

The findings were published in the highly respected journal Nature Scientific Reports and the response was immediate and explosive.

Shock waves rippled through the scientific community.

The researchers [music] had expected a clear dominant genetic signal.

If the shroud were a medieval forgery created in France, as skeptics have long claimed, then European DNA, specifically French or Italian, should have overwhelmingly dominated the results.

If instead it were an authentic relic originating in Jerusalem and never leaving the region, then the genetic traces should have pointed almost entirely to the Middle East.

That is not what appeared.

What emerged instead was something closer to chaos.

An entire world recorded on a single piece [music] of cloth.

The shroud revealed genetic fingerprints from people spanning vast regions of Eurasia and Africa.

Let’s look at what the scientists [music] found.

First, the Middle East.

Researchers identified Haplo groups commonly associated with the Drews, [music] a tightlyknit and historically isolated ethnoreigious community living in the mountainous regions of Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria.

Drew’s DNA is considered exceptionally ancient and remarkably stable, having changed very little over thousands of years due to centuries of isolation.

This makes it a powerful marker of geographic origin and provides strong evidence of a Middle Eastern connection.

Second, Western European HLO groups such as U5B and H1 through H3 also appeared exactly as expected.

Since the 15th century, the shroud has been kept in Europe, first in Shamberee and later in Tan.

Over the [music] centuries, the cloth was handled by the poor CLA’s nuns who repaired it, by members of the House of Seavoy who owned it and by countless European pilgrims who came to [music] venerate it.

Then came the third region, North and East Africa.

Haplo group L3 CM101 appeared, pointing toward areas such as Egypt and Ethiopia.

This was both unexpected and deeply fascinating, suggesting contact with some of the [music] earliest Christian communities on the African continent.

Fourth was South Asia.

Haplo [music] groups M39, M56 and R8 were identified, genetic markers typical of the Indian subcontinent.

And most astonishing of all were traces from East Asia.

Haplo groups such as D4 and G2A commonly associated with China were present.

[music] China, India, Africa, Europe, the Middle East.

All of it encoded into a single ancient [music] cloth.

How could this possibly be explained? If the shroud were merely a forgery created in the damp basement of a French abbey around the year 1350, how could genetic traces from China and India be present at all? [music] In the medieval world, globalization did not exist.

Long-distance travel did occur, but not on a scale vast enough to leave such widespread, [music] clearly identifiable genetic signatures on one piece of fabric.

The answer, it turned out, was even more extraordinary than the mystery itself.

[music] The shroud is not simply a burial cloth.

It is a traveler.

When scientists [music] in Padua mapped the genetic data, they made a stunning discovery.

The distribution of genetic markers aligned with remarkable geographic precision [music] along an ancient historical route, one that many scholars had long dismissed as little more than legend.

The answer lies in the journey of the man-made image known as the Mandelion.

[music] According to early Byzantine, Syrian and Arabic sources, the shroud was folded in such a way that only the face was visible and displayed inside a special frame.

This folded form was known as the tetra diplolon folded in four.

This relic did not remain in one place and it certainly did not begin in Europe.

Its journey started in Jerusalem, the site of crucifixion and resurrection.

From [music] there it traveled to Adessa in the second century.

The shroud remained hidden within the city walls for centuries [music] before being rediscovered.

Adessa stood at one of the most important crossroads of the ancient world.

[music] The Great Silk Road.

Caravans from China, India, Persia, and Arabia passed through the city.

Merchants carrying silk and spices.

Pilgrims and diplomats from distant lands.

all came to venerate the relic believed to protect the city.

They stood close to it.

They kissed its casing.

They touched the relicer.

And with every encounter, microscopic traces, skin cells, hair fragments, droplets [music] of sweat settled onto the cloth.

Layer by layer, century after century, [music] the DNA of the world accumulated on its surface like invisible dust.

The journey didn’t end there.

Next [music] came Constantinople.

From 944 until 124, the relic was kept at the very heart of the Byzantine Empire.

The emperors of Bzantium acquired it by purchase or by force [music] and brought it to what was then the greatest city on earth.

Constantinople was a true mega city of the ancient world, a [music] place where people of every race, culture, and region converged.

Then in 1204 [music] during the chaos of the fourth crusade, the city was violently looted.

[music] In the aftermath, the shroud disappeared.

Its next stop appears to have been Athens and the wider region of Greece [music] around 1205.

After the fall of Constantinople, the relic passed into the hands of French knights [music] and was kept in Athens for a time before vanishing once again into history.

Then comes France around the year 1353.

This is the [music] shroud’s first clearly documented appearance in Western Europe in the possession of the knight Jethro Desani.

[music] And it is here that the genetic evidence delivers a devastating blow to the medieval forgery theory.

A forger working in Europe during the 14th or 15th century could not possibly have collected dust [music] and DNA from people in China, India, the Middle East, and Africa.

Regions known only through distant travelers [music] tales like those of Marco Polo.

Nor could such a person have intentionally planted those traces on a cloth in a way that would fool genetic scientists 600 years later.

The DNA found on the shroud is not random contamination.

It is a collective biological memory.

Dust from sandals, robes, and hands left behind by countless people who stood before this face over many centuries.

This biological record demonstrates the object’s great age [music] and its eastern origins more convincingly than any radiocarbon test ever could.

But human DNA tells only half the [music] story.

The other half is written in plants.

Palinology, the study of pollen, provided another critical piece of the puzzle.

Two highly respected experts approached [music] the mystery independently.

Professor Aanome Darnan, a renowned Israeli botonist from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and [music] Max Frey, a Swiss forensic scientist and pioneer in pollen analysis.

Working separately, they examined pollen grains trapped deep [music] within the linen fibers.

Using adhesive sampling techniques, they carefully lifted microscopic traces from the cloth.

What they discovered sent shock waves through the botanical community.

Pollen from 58 different plant species was identified on the shroud.

17 of those species are native to Europe.

Exactly what we would expect given [music] the shroud’s documented presence there over the last six centuries.

But the majority came from elsewhere.

plants native to the Middle East, Turkey, and the Anatolian step, [music] perfectly matching the ancient route through Adessa and Constantinople.

Then came the most extraordinary discovery of all.

Scientists identified a group of plants [music] that grow nowhere else on Earth, species found only within a narrow geographic corridor between Jerusalem and Jericho.

At the center of this finding was one plant in particular, Gandelia Turner, a thorny desert shrub, a type of thistle.

Its pollen made up nearly half of all the samples recovered from the cloth, an unusually high and deeply puzzling concentration.

Why would pollen from a thorncovered plant be so dominant? And why would thorns be linked to the burial cloth of a man treated as a king? The answer emerged when historians and theologians revisited the accounts of Christ’s passion.

The crown of thorns, Gundelia Tornaforti, with its long, stiff, needle-like spines is exactly the type of plant Roman soldiers could have twisted into a cruel mock crown for the so-called king of the Jews.

Suddenly, the pollen began to tell its story.

This plant blooms near Jerusalem at a very specific time of year, early spring, coinciding precisely with the Jewish festival of Passover.

The discovery of such an unusually dense concentration of its pollen, especially around the head and shoulder areas of the cloth, provides direct physical evidence that the body was crowned with thorns.

A second botanical clue came from zygraphilum demosum, a plant endemic to a very restricted region growing only in the Judean desert and parts of the Sinai Peninsula.

Its pollen was also found on the fabric in significant quantities.

No medieval forger working in France could have obtained pollen from plants native exclusively to Israel, let alone applied it invisibly at a microscopic level across a piece of cloth.

A forger would have used paint.

Pollen cannot be painted.

It functions like an invisible seal from a crime scene, a geographic fingerprint that cannot be faked.

For many years, especially during the highly rational 19th century, skeptics argued that the reddish stains on the shroud were nothing more than pigments, ochre, cineabar, or tempera mixed with gelatin.

That claim finally collapsed in 2017.

A team of Italian researchers led by professor Julio Fanti of the University of Padua working alongside physicians from a hospital in Trieste examined the stains using transmission electron microscopy and ramen spectroscopy.

At the nanocale they saw not pigment but blood.

The blood found on the cloth was identified as human and of blood type AB, one of the rarest blood groups in the world.

Yet this same blood type appears repeatedly on ancient Christian relics including the sudarium of ovdo.

But this was not the blood of a healthy person.

Within it, scientists detected nano particles of creatinine and feritin bound to hemoglobin.

Such extreme concentrations occur under only one set of conditions.

Catastrophic fatal trauma.

Prolonged torture combined with dehydration and massive muscle destruction.

When muscle tissue is repeatedly damaged, a process known as rabdtoiolysis, creatinine floods the bloodstream in enormous amounts and the blood preserved on the cloth recorded exactly that.

This is not symbolism.

It is a biochemical scream of pain.

The analysis revealed that the man wrapped in this cloth did not simply die.

He was beaten to a physical state already incompatible with life before crucifixion even began.

This matches the gospel descriptions of Roman scourging carried out with the flag room, leather whips embedded with lead weights.

The body bears evidence of more than 100 blows, and the chemistry of the blood tells a story of suffering that no artist could ever fake.

A painter can imitate the appearance of a wound, but no human hand can reproduce the biochemical signature of extreme trauma, poly trauma, kidney failure, and hypoalmic shock.

Another long-standing mystery was the color of the blood.

The stains on the cloth remain red.

Normally, ancient blood darkens over time, turning brown or black.

But scientific analysis revealed unusually high levels of bilerubin, a substance released by the liver during extreme stress and severe trauma.

Bilerubin preserves the red color of blood for centuries.

The blood of a tortured man stays red.

This is not mysticism.

It is biochemistry under unbearable stress.

At this point, many people ask the same question.

What about the famous radiocarbon dating? In 1988, carbon 14 testing seemed to settle the debate once and for all.

Three of the world’s most respected laboratories, Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona, released their findings with 95% confidence.

According to their measurements, the fabric dated to between 1260 and 1390, the Middle Ages, a forgery.

The world accepted the verdict.

Even the church stepped back, referring to the shroud as an icon rather than a true relic.

But science does not stand still.

Three decades later, researchers discovered where the critical mistake had been made.

The problem was not the technology.

It was the human decision of where to take the sample.

In 1988, a tiny piece of fabric no larger than a postage stamp was cut from the very edge of the shroud.

That corner had been handled countless times over the centuries.

Gripped by bishops and cardinals during public exhibitions.

It absorbed sweat, skin oils, candle wax, bacteria.

It suffered more wear and contamination than any other part of the cloth.

Further investigation by chemist Ray Rogers of Los Alamos National Laboratory revealed something even more troubling.

That corner had been expertly repaired during the Middle Ages, so skillfully that the repair went unnoticed.

The sample was not representative of the shroud as a whole.

With that realization, the certainty of the 1988 results began to fall apart.

The French nuns who restored the shroud did not use modern invisible mending techniques.

Instead, they reinforced the damaged edge by weaving new cotton threads into the original fabric, carefully dyed to match the color of the aged linen.

Later chemical analysis of the exact sample tested in 1988 revealed the presence of cotton fibers.

That alone raised serious concerns.

The main body of the shroud contains no cotton at all.

It is made entirely of linen.

To disguise the repair, the cotton threads were colored with alazarin dye to blend with the older fabric and gum arabic was used as a binding agent.

In other words, the material tested in 1988 was not original.

The laboratories dated the patch, not the shroud itself.

What they actually measured was the age of medieval cotton and [clears throat] centuries of accumulated grime, not the original first century linen.

This was not a small mistake.

It was a major sampling error and a clear violation of basic archaeological practice.

Dating the most contaminated and heavily repaired section of an artifact is like trying to determine the age of an ancient statue by analyzing the chewing gum stuck to its base.

Once this flaw was recognized, scientists began searching for a method that could completely bypass contamination.

In 2022, Italian physicist Liberato Decaro from the Institute of Crystalallography in Bari introduced a radically different approach, one that does not depend on organic residues at all.

The technique is known as wide-angle X-ray scattering or WAXs and it changed everything.

Instead of analyzing contaminants, this method examines the aging of the linen itself, specifically the cellulose inside its fibers, measured at the atomic level.

Over time, linen naturally degrades.

The long polymer chains of cellulose slowly break apart and its crystalline structure deteriorates under constant exposure to background radiation, humidity, and temperature.

This process functions as the material’s internal clock.

Daro compared samples from the shroud with fabrics of known age, ranging from linen used to wrap Egyptian mummies dating back to 3000 BC to medieval textiles from the 10th through the 14th centuries.

The results stunned researchers.

The aging curve of the shroud cellulose did not match medieval fabrics at all.

It was far older.

In fact, the molecular structure of the shroud’s linen, aligned with striking precision to linen fragments, recovered from the fortress of Msada in Israel.

Msada fell in 74 AD, and the textiles found there are dated between 50 and 74 A, squarely within the first century, the time of Christ.

Using advanced X-ray analysis, scientists pushed the age of the Turan Shroud back more than a thousand years, placing its origin in the very heart of biblical history.

In 1988, science appeared to dismiss the miracle.

In 2022, armed with modern tools, it brought it back to life.

But one question still remains.

How did the image form? There are no brush strokes, no pigments, no ink.

The image exists only on the very surface of the linen, about 200 nanome deep, hundreds of times thinner than a human hair.

Scrape it lightly and it disappears.

This is not paint.

It is a chemical transformation caused by oxidation and dehydration.

[clears throat] A kind of scorch left behind by an unknown source of energy.

Scientists tried everything to recreate it.

Acids, heat, gamma radiation.

Nothing worked.

Only one method came close.

A brief intense pulse of vacuum ultraviolet radiation.

But such lasers did not exist in the ancient world.

[snorts] To imprint the image across nearly four square meters of fabric, the body would have had to release an unimaginable burst of energy lasting less than a billionth of a second.

Powerful enough to mark the cloth, yet precise enough not to burn or destroy it.

In 1976, technology developed by NASA revealed something even more astonishing.

The shroud contains a perfectly accurate three-dimensional image.

The intensity of the imprint corresponds exactly to the distance between the body and the cloth.

This is something no artist, ancient or modern, has ever been able to replicate.

Even more remarkable, digital analysis revealed shapes over the eyes consistent with coins, matching rare leptons minted under Ponteus Pilot around 29 A.

The likelihood that a medieval forger could have known or reproduced this detail is effectively zero.

The cloth also carries dust from Jerusalem, pollen from plants that bloom only near the city in early spring, and blood containing biochemical markers of extreme torture.

The nails pass through the wrists, not the palms, exactly as forensic science predicts.

Even nerve responses are visible, including the retraction of the thumbs, layer by layer, discipline by discipline.

Biology, chemistry, physics, geology, history, numismatics.

All the evidence converges on one place in one time.

Jerusalem between 30 and 33 a.

The shroud resists simple explanation.

It is not a painting.

It is a holographic-like imprint of a real human being, a forensic record, a silent witness to a moment that altered the course of history.

returned to its vault.

The shroud remains quiet, but the data does not.

Legend, faith, and tradition are now supported by measurable scientific evidence.

Perhaps one day we will fully understand the burst of energy that left this trace behind.

Until then, it stands as a fifth gospel written not in words, but in matter itself.

So, the question remains, do you believe science will one day explain a miracle? Or are some doors meant to stay open not to the mind but to the heart?

News

Girl In Torn Clothes Went To The Bank To Check Account, Manager Laughed Until He Saw The Balance What If Appearances Lied So Completely That One Look Cost Someone Their Dignity—and Another Person Their Job? What began as quiet ridicule quickly turned into stunned silence when a single number appeared on the screen, forcing everyone in the room to confront their assumptions. Click the article link in the comment to see what happened next.

Some people only respect you when they think you’re rich. And that right there is the sickness. This story will…

Billionaire Goes Undercover In His Own Restaurant, Then A Waitress Slips Him A Note That Shocked Him

Jason Okapor stood by the tall glass window of his penthouse, looking down at Logos. The city was alive as…

Billionaire Heiress Took A Homeless Man To Her Ex-Fiancé’s Wedding, What He Did Shocked Everyone

Her ex invited her to his wedding to humiliate her. So, she showed up with a homeless man. Everyone laughed…

Bride Was Abandoned At The Alter Until A Poor Church Beggar Proposed To Her

Ruth Aoy stood behind the big wooden doors of New Hope Baptist Church, holding her bouquet so tight her fingers…

R. Kelly Victim Who Survived Abuse as Teen Breaks Her Silence

The early 2000s marked a defining moment in popular culture, media, and public conversation around fame, power, and accountability. One…

Las Vegas Bio Lab Sparks Information Sharing, Federal Oversight Concerns: ‘I’m Disappointed’

New questions are emerging over why a suspected illegal biolab operating from a residential home in the East Valley appeared…

End of content

No more pages to load