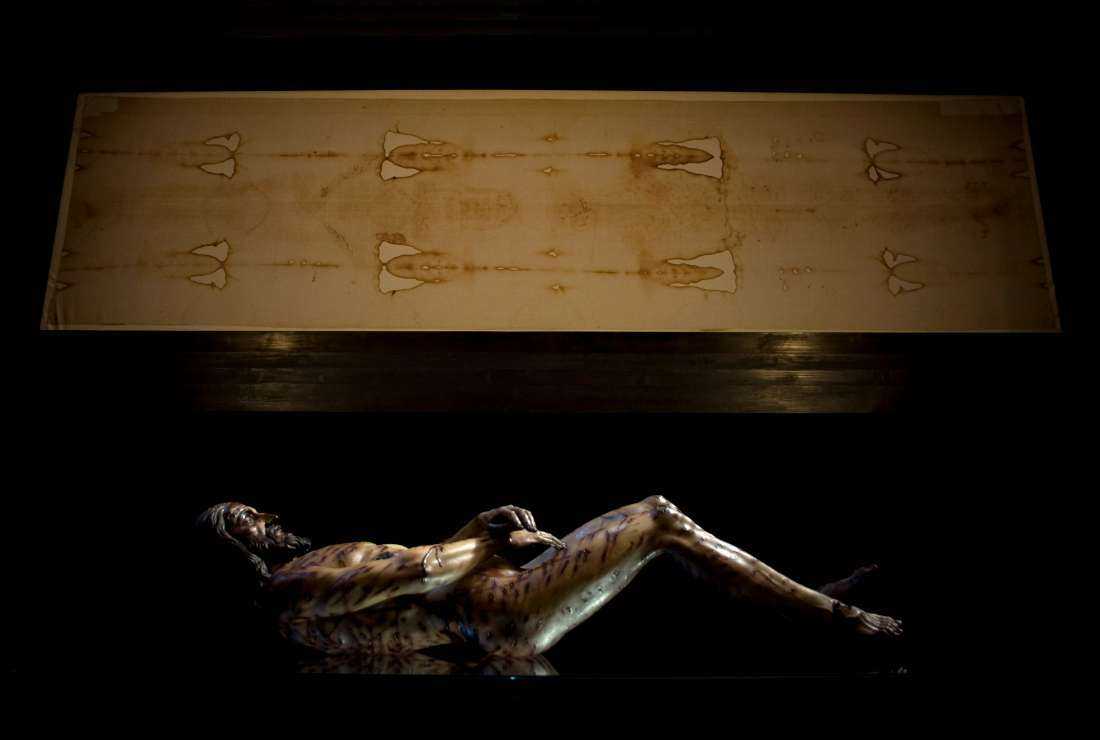

Few artifacts in human history have inspired as much fascination, devotion, skepticism, and scientific scrutiny as the Shroud of Turin.

Preserved today in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, the linen cloth bears the faint front and back image of a crucified man.

For believers, it is the burial cloth of Jesus Christ.

For skeptics, it is a masterwork of medieval ingenuity.

For scientists, it has become one of the most intensively examined objects on Earth, a textile that functions almost like a biological archive.

Over more than a century, researchers have subjected the shroud to photography, spectroscopy, radiocarbon dating, forensic pathology, palynology, and advanced genetic sequencing.

Each wave of investigation has deepened the mystery rather than resolved it.

The most recent phase, focused on DNA analysis and nanoscopic examination of blood residues, has reopened fundamental questions about the cloth’s origin, age, and journey across continents.

The first scientific turning point came in 1898.

During a public exhibition in Turin, an amateur photographer named Secondo Pia was granted permission to photograph the relic.

Working under difficult conditions with large glass plates and magnesium flash powder, he captured what appeared to be a faint, almost indistinct image on the linen.

But when he developed the photographic negatives in his darkroom, he was stunned.

The negative revealed a detailed positive image of a man’s face, with defined features, closed eyes, a beard, and marks consistent with physical trauma.

The discovery transformed the debate.

On the cloth itself, the image appears faint and inverted in tonal values.

In photographic negative form, however, it displays natural light and shadow gradations consistent with a three dimensional human form.

This unexpected property challenged the notion of a conventional painted forgery.

Medieval artists did not possess knowledge of photographic principles, nor did they have a way to preview how a negative image would appear centuries before photography was invented.

In the decades that followed, researchers examined the cloth using X rays, ultraviolet fluorescence, infrared reflectography, and digital image processing.

Teams treated the fabric as forensic evidence rather than a devotional object.

They mapped bloodstains, analyzed fiber degradation, and searched for pigments.

Many expected to find traces of paint or dye that would confirm an artistic origin.

Instead, chemical studies repeatedly showed that the image resides only on the outermost fibrils of the linen threads, penetrating less than a fraction of a millimeter.

The 21st century introduced an even more ambitious line of inquiry: genetic analysis.

A team of researchers from the University of Padua, led by Professor Gianni Barcaccia, applied next generation sequencing techniques to microscopic particles vacuumed from the cloth’s surface and from archived samples collected during earlier restorations.

Their objective was not to identify a single individual, but to reconstruct the biological history embedded within the fibers.

Mitochondrial DNA became the focus because it survives longer than nuclear DNA and exists in multiple copies per cell.

Using sterile microvacuum devices equipped with ultrafine filters, scientists collected dust, pollen, and organic fragments trapped between warp and weft threads.

These samples were processed in ultra clean laboratories to minimize contamination from modern handlers.

When sequencing results were compared with global genetic databases, the outcome was complex.

Instead of a single dominant genetic signature, researchers identified multiple mitochondrial haplogroups associated with populations from diverse geographic regions.

Genetic traces linked to the Middle East were present, including lineages common among communities historically rooted in the Levant.

Western European haplogroups also appeared, consistent with the shroud’s documented presence in France and Italy since the late medieval period.

Unexpectedly, markers associated with North and East Africa were detected, along with haplogroups typical of the Indian subcontinent and East Asia.

These findings suggested that the cloth had been in contact with individuals from a broad spectrum of Eurasian and African populations.

Critics argue that centuries of handling by pilgrims and clergy could easily explain such diversity.

Supporters counter that the distribution aligns intriguingly with historical trade and pilgrimage routes linking Jerusalem, Edessa, Constantinople, and Western Europe.

The genetic data were published in a peer reviewed journal, prompting intense discussion.

Some scholars emphasized that DNA on an artifact reflects cumulative contact rather than original ownership.

Others noted that certain ancient lineages, particularly those associated with the Near East, appeared prominently.

While the findings did not definitively prove an origin in first century Judea, they complicated the theory of a simple medieval European creation.

Parallel to genetic research, palynology offered another line of evidence.

Swiss forensic expert Max Frei and Israeli botanist Avinoam Danin independently examined pollen grains lifted from the linen using adhesive tapes.

They identified dozens of plant species.

Some were native to Europe, consistent with the shroud’s later history.

Others originated in Anatolia and the Middle East.

A subset of pollen types corresponded to plants that grow in the region between Jerusalem and Jericho.

One plant frequently discussed in this context is Gundelia tournefortii, a thorny species found in the Near East.

Its pollen appeared in notable concentrations on certain areas of the cloth.

Danin argued that the bloom period of this plant coincides with springtime in Jerusalem.

While pollen analysis is subject to debate, the presence of Middle Eastern species reinforced the possibility of early contact with that region.

Forensic examination of the reddish stains has also evolved.

Early skeptics proposed that the marks were iron oxide pigments or tempera.

Later studies using spectroscopy and electron microscopy identified hemoglobin and other components consistent with human blood.

In 2017, Italian researchers reported detecting nanoparticles of creatinine and ferritin bound to hemoglobin.

Such compounds can be associated with severe physical stress and tissue damage.

The blood type identified in several analyses was AB.

Although relatively uncommon globally, AB is not rare in the Middle East.

The presence of bilirubin, a pigment produced during the breakdown of red blood cells and elevated under intense stress, may explain why the stains retain a reddish hue rather than darkening completely over time.

Critics caution that contamination and environmental factors complicate interpretation.

The cloth has been exposed to fires, water, handling, and restoration procedures over centuries.

A significant fire in 1532 caused water damage and scorch marks that required repairs.

Each event introduced potential chemical alterations.

Nonetheless, multiple independent laboratories have confirmed that the image itself is not composed of conventional pigments.

Radiocarbon dating performed in 1988 dated the cloth to the period between 1260 and 1390.

That result has been central to the medieval forgery argument.

However, some researchers contend that the samples tested may have come from a repaired section or were affected by contamination.

Calls for renewed dating using more advanced techniques continue, though access to the cloth is tightly controlled.

Another striking feature is the three dimensional information encoded in the image.

When analyzed with digital image processing systems, brightness variations correlate with distance between the body and the cloth, suggesting a form of spatial encoding.

Experiments attempting to replicate the image using heat, chemicals, or artistic methods have produced partial similarities but not an exact match in terms of superficiality and resolution.

The shroud’s documented history begins in the 14th century in France, where it was displayed in Lirey.

From there, it passed into the possession of the House of Savoy and was eventually transferred to Turin.

Earlier references to a cloth bearing the image of a man, sometimes called the Image of Edessa or Mandylion, appear in Byzantine sources.

Some historians speculate that this object and the shroud may be connected, though definitive proof remains elusive.

For believers, the convergence of image properties, blood chemistry, pollen distribution, and genetic diversity strengthens the case for authenticity.

For skeptics, the same data illustrate how a heavily handled medieval relic can accumulate complex biological traces over time.

Both sides agree on one point: the shroud resists simple explanation.

Modern science approaches the cloth not as a sacred icon nor as a hoax, but as material evidence.

Each fiber holds chemical signatures shaped by history.

Each microscopic particle may reflect a human encounter across centuries.

Genetic sequencing has revealed a tapestry of global contact, a biological map of pilgrims, traders, clergy, and custodians.

Whether the shroud originated in first century Jerusalem or in medieval Europe, its cultural impact is undeniable.

It has inspired art, theology, and scientific innovation.

It has endured fire, restoration, and intense scrutiny.

In laboratories, researchers continue to debate the mechanisms that could produce such an image on linen without pigments or deep penetration.

The Shroud of Turin remains suspended between faith and empirical inquiry.

DNA analysis did not deliver a final verdict, but it expanded the conversation.

It demonstrated that the cloth is not a simple, isolated artifact.

It carries within its threads the biological residue of a vast human network stretching from the Middle East to Europe and beyond.

In an age defined by advanced imaging, molecular biology, and high energy physics, the shroud continues to challenge assumptions.

It invites both devotion and doubt.

More than a relic, it has become a case study in how science engages with history, tradition, and mystery.

As new technologies emerge, the linen in Turin will likely face further examination.

For now, it stands as one of the most studied and debated textiles ever preserved, a silent witness to centuries of human curiosity.

News

Apollo 11 Astronaut Reveals Spooky Secret About Mission To Far Side Of The Moon! 10t

The Apollo 11 mission remains one of humanity’s greatest achievements, a defining moment when human beings first set foot on…

Bruce Lee’s Daughter in 2026: The Last Guardian of a Legend 10t

As a child, Shannon Lee would sometimes respond to playground bravado with quiet certainty. When other children joked that their…

Selena Quintanilla Died 30 Years Ago, Now Her Husband Breaks The Silence Leaving The World Shocked 10t

Thirty years have passed since the world lost one of Latin music’s brightest stars, yet the name Selena Quintanilla continues…

Scientists New Plan To Retrieve the Titanic Changes Everything! 10t

More than a century after the RMS Titanic slipped beneath the icy waters of the North Atlantic, the legendary ocean…

Drunk Dancer Challenged Michael Jackson — His Response Stunned 80,000 Fans

July 16th, 1989, Wembley Stadium. 80,000 people watched as a drunk backup dancer stumbled onto the stage during Billy Jean…

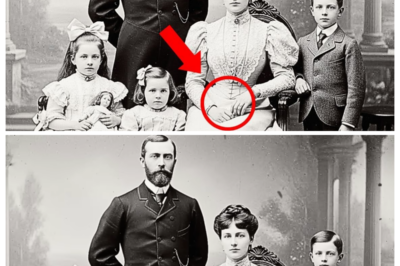

1890 Family Portrait Discovered — And Historians Recoil When They Enlarge the Mother’s Hand

This 1890 family portrait is discovered, and historians are startled when they enlarge the image of the mother’s hand. The…

End of content

No more pages to load