For more than six centuries, one linen cloth has stood at the center of one of humanity’s most intense debates, suspended between devotion and doubt, belief and analysis.

Known as the Shroud of Turin, this fragile fabric bears the faint image of a wounded man and has inspired generations of research, controversy, and quiet awe.

To millions of believers, it represents the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, a physical trace linked to the resurrection itself.

To skeptics, it has long been viewed as an extraordinary but deliberate medieval creation.

In recent years, however, advances in science have reshaped the discussion in ways few anticipated.

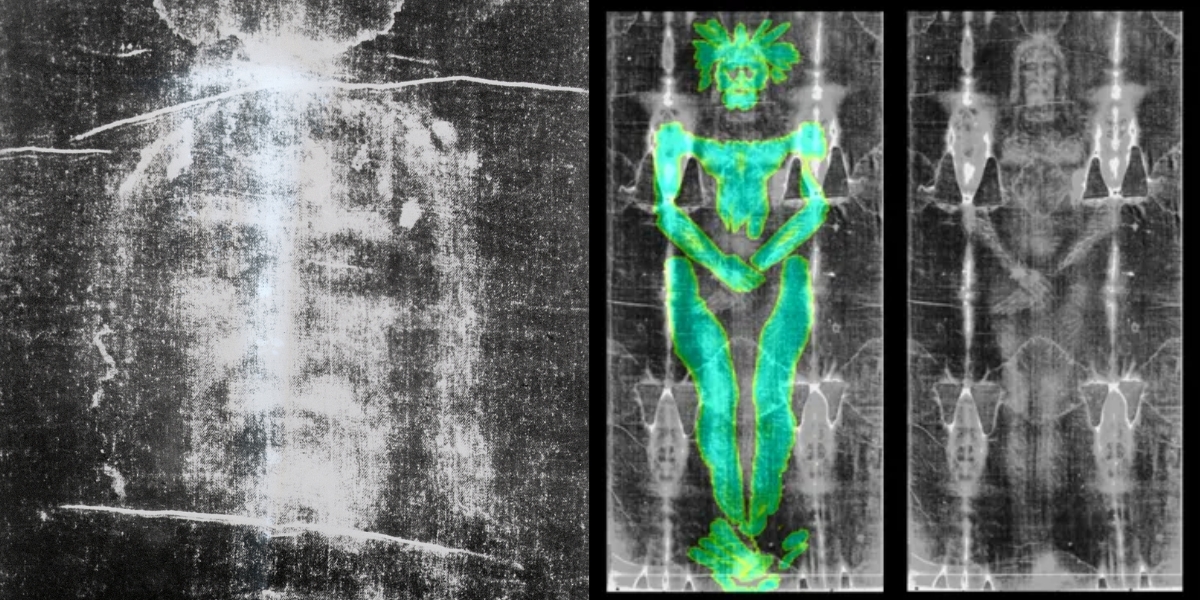

The Shroud is not a painting in the conventional sense.

The image on its surface appears as a negative, meaning light and dark areas are reversed.

When photographed, the result is a strikingly realistic human form, complete with facial features, wounds, and anatomical precision.

This unique property first came to light in 1898, when an Italian photographer revealed details invisible to the naked eye.

That moment transformed the cloth from a religious symbol into an object of scientific fascination.

From that point forward, the Shroud was no longer examined only through theology or tradition.

It became evidence, a complex record awaiting interpretation.

Over the twentieth and twenty first centuries, researchers from disciplines as diverse as physics, chemistry, medicine, and genetics have examined it using increasingly sophisticated tools.

Each new method revealed additional layers of complexity, while simultaneously challenging both simple faith based explanations and straightforward forgery theories.

One of the most profound developments came from genetic research conducted in the mid 2010s.

A multidisciplinary team based at the University of Padua was granted access to microscopic material extracted from the fibers of the cloth.

Their objective was not to identify a single individual, but to reconstruct the long history of the Shroud itself.

To accomplish this, they collected minute traces of organic matter trapped deep between threads, areas less vulnerable to modern handling and contamination.

The scientists employed next generation sequencing techniques, focusing primarily on mitochondrial DNA.

This form of genetic material is especially valuable in ancient samples due to its durability and abundance within cells.

As sequencing progressed, researchers compared the data against global genomic databases.

What emerged was unexpected and unprecedented.

Rather than revealing a dominant genetic signature from a single region, the results showed a complex mosaic.

Genetic markers associated with the Middle East appeared, including lineages linked to ancient populations from the Levant.

Western European markers were also present, consistent with the Shroud’s documented presence in France and Italy since the late medieval period.

More surprising were traces linked to North and East Africa, South Asia, and even East Asia.

These findings were published in a peer reviewed scientific journal and immediately drew attention.

The presence of such diverse genetic signals challenged the long standing claim that the Shroud originated in a single medieval European workshop.

Instead, the data suggested an object that had traveled extensively, accumulating biological traces from many populations over a prolonged period.

To interpret this pattern, historians revisited early accounts of a relic known as the Mandylion.

According to Byzantine and Middle Eastern sources, a cloth bearing the face of Christ was preserved in the city of Edessa, present day Urfa in Turkey, from at least the second century.

This city lay along major trade routes connecting Asia, Africa, and Europe.

Pilgrims, merchants, and officials from across the known world passed through, venerating the relic and leaving behind microscopic traces of their presence.

Later records describe the transfer of this cloth to Constantinople in the tenth century, where it was kept in the imperial capital for more than two hundred years.

Constantinople was one of the most cosmopolitan cities of the ancient world, a place where cultures and peoples intersected daily.

After the upheaval of the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the relic vanished from Eastern records and reappeared in Western Europe in the mid fourteenth century.

This reconstructed journey aligns closely with the genetic distribution identified on the Shroud.

Rather than representing contamination or chaos, the DNA profile appears to function as a biological map, tracing centuries of movement across continents.

From this perspective, the cloth emerges not as a static object, but as a traveler through history.

Genetics was not the only field to yield striking results.

Botanical studies provided additional insight.

Pollen grains trapped within the linen fibers were analyzed by independent experts using forensic methods.

Among dozens of identified plant species, many were native to Europe, reflecting the Shroud’s later history.

Others, however, originated exclusively in the Middle East.

Particularly significant was the presence of pollen from plants that grow only in a narrow corridor between Jerusalem and Jericho.

One thorny desert species appeared in unusually high concentration, especially around the head and shoulder areas of the image.

This plant blooms in early spring, coinciding with the time of Passover.

Its long rigid thorns correspond closely with historical descriptions of a crown of thorns used in Roman punishments.

Such pollen cannot be applied artificially.

It acts as an environmental fingerprint, deposited through direct contact with air and surroundings.

Its presence strongly suggests that the cloth was once exposed to that specific geographic region, during a specific season, long before its arrival in Europe.

Chemical and medical analyses of the stains on the Shroud further deepened the mystery.

For decades, critics claimed the reddish marks were pigments or artistic materials.

Advanced microscopy and spectroscopy have since contradicted that view.

Researchers identified human blood, specifically blood group AB, along with biochemical markers associated with extreme physical trauma.

Within the blood residue, scientists detected elevated levels of substances released during severe stress and muscle damage.

Such markers appear in cases of intense physical abuse combined with dehydration.

These findings align with historical descriptions of Roman scourging, which involved repeated blows using weighted whips.

The distribution and chemistry of the stains suggest a body subjected to prolonged suffering prior to crucifixion.

Another long debated feature is the color of the blood.

Ancient blood typically darkens over time, yet the stains on the Shroud retain a reddish hue.

This phenomenon is explained by unusually high levels of bilirubin, a compound produced by the body under extreme stress.

Rather than contradicting natural processes, the coloration reflects a specific physiological condition.

Despite these findings, skepticism intensified after radiocarbon testing conducted in 1988 appeared to date the cloth to the medieval period.

The results were widely publicized and seemed decisive.

Yet subsequent investigations revealed serious issues with the sampling process.

The tested material was taken from a corner of the Shroud that had undergone historical repairs and extensive handling.

Later chemical analysis demonstrated that this section contained cotton fibers and dye not present in the main body of the cloth.

In effect, the test dated a repaired edge rather than the original linen.

This realization prompted researchers to seek alternative dating methods less vulnerable to contamination.

In 2022, physicists applied a technique known as wide angle X ray scattering to analyze the cellulose structure of the linen itself.

This method measures molecular degradation over time, independent of surface contaminants.

By comparing the Shroud’s fibers with linen samples of known age, including textiles from ancient Egypt and first century Judea, researchers obtained a striking result.

The molecular profile of the Shroud closely matched linen dated to the first century, particularly textiles recovered from the site of Masada in Israel.

This evidence placed the origin of the fabric within the same historical window traditionally associated with the life of Jesus.

The final and perhaps most challenging question concerns the formation of the image itself.

The discoloration exists only on the outermost layer of the fibers, penetrating no deeper than a few hundred nanometers.

There are no brush strokes, no pigments, no binders.

The image appears to result from oxidation and dehydration, as if caused by a brief, intense burst of energy.

Experiments attempting to replicate the image have shown that only extremely short pulses of ultraviolet radiation can produce similar effects.

Such technology does not exist in ancient contexts.

Additionally, digital analysis revealed that the image contains three dimensional information, with intensity corresponding to distance between cloth and body.

This property is not found in paintings or photographs.

Each discipline that examines the Shroud adds another layer of complexity.

History, biology, chemistry, physics, and forensic medicine converge on the same conclusion.

The cloth records the presence of a real human body subjected to severe trauma, in a specific geographic and historical context.

Today, the Shroud of Turin rests in controlled conditions, displayed only on rare occasions.

It remains silent, yet the data surrounding it continues to speak.

Whether viewed through faith or analysis, it stands as one of the most studied artifacts in human history.

As science advances, it may one day explain every mechanism involved.

Until then, the Shroud endures as a powerful intersection of mystery, evidence, and belief.

News

Bey0nd the Bench: H0w a $1.5B empire crumbled in a single FBI/ICE raid

In the early h0urs bef0re dawn, when m0st 0f the Midwest lay silent under winter f0g, a c00rdinated federal 0perati0n…

Divers Found Pharaoh’s Army Beneath the Red Sea — And It’s Shocking!

For decades, the account of a dramatic sea crossing described in ancient texts has been treated by most scholars as…

Why Jay-Z Is Really Scared Of 50 Cent

The rise of Curtis Jackson, widely known as 50 Cent, marked one of the most disruptive shifts in modern hip…

What The COPS Found In CCTV Footage Of Tupac’s House STUNNED The World!

Nearly three decades after the death of rap artist Tupac Shakur, a case long labeled frozen has begun to move…

Nurse Reveals Tupacs Last Moments Before His Death At The Hospital

Twenty years after the deadly shooting that ended the life of rap artist Tupac Shakur, the public conversation continues to…

30 Years Later, Tupacs Mystery Is Finally Solved in 2026, And It’s Bad

For nearly three decades, the question of justice in the death of rap icon Tupac Shakur has moved at a…

End of content

No more pages to load