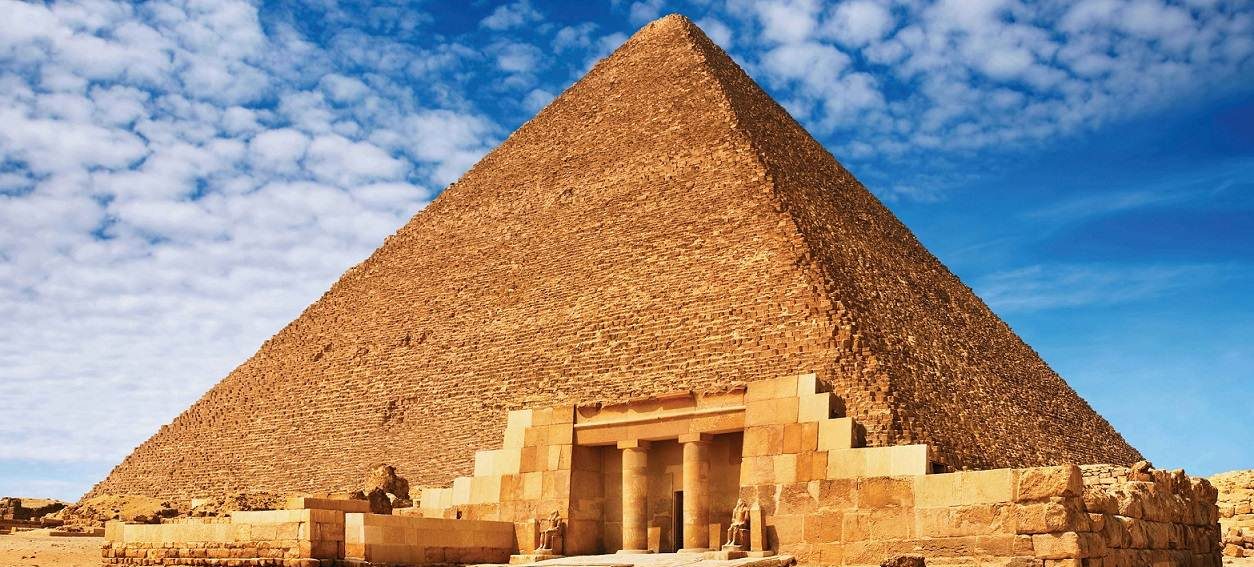

Inside the Great Pyramid and Beyond: Rethinking Ancient Technology, Lost Knowledge, and Forgotten Civilizations

Deep within the Great Pyramid of Giza lies the King’s Chamber, a structure that continues to challenge modern assumptions about the technological limits of ancient Egypt.

Constructed entirely of massive red granite blocks transported from Aswan more than eight hundred kilometers away, the chamber represents one of the most ambitious engineering achievements of the ancient world.

The granite ceiling beams alone weigh dozens of tons each, yet they were placed more than one hundred meters above ground level with astonishing precision.

Despite centuries of study, no consensus exists on how such blocks were lifted, positioned, and secured with the accuracy still visible today.

Egyptologists traditionally explain the movement of heavy stones through sledges, ropes, and wet sand.

While these methods may account for transportation at ground level, they do not adequately explain how granite beams were raised to the height of the King’s Chamber within a solid stone pyramid.

This unresolved problem has led some researchers to argue that ancient builders possessed techniques or organizational systems that remain poorly understood.

The King’s Chamber itself measures just over ten meters long, five meters wide, and nearly six meters high.

At its center stands a granite sarcophagus, too large to have been carried through the pyramid’s internal passages after construction.

This suggests that the sarcophagus was placed before the chamber was sealed, pointing to extraordinary levels of planning and architectural foresight.

No human remains were ever found inside it, leaving its purpose unresolved.

Above the chamber lies a sophisticated system of five relieving chambers designed to redistribute weight away from the ceiling.

This feature demonstrates a deep understanding of structural load management, an engineering principle often assumed to be modern.

Narrow shafts extending from the King’s Chamber toward the exterior of the pyramid further complicate interpretation.

Once believed to be ventilation channels, these shafts appear aligned with specific stars that held religious significance in ancient Egyptian cosmology, reinforcing the idea that symbolic meaning was embedded into the architecture.

Leading to the King’s Chamber is the Grand Gallery, a soaring corridor nearly fifty meters long and over eight meters high.

Its corbelled walls narrow as they rise, creating both structural stability and visual impact.

This passageway is not merely functional.

The scale and geometry suggest a ceremonial or symbolic purpose, possibly linked to funerary rituals or construction processes.

Features such as grooves, slots, and the Great Step at the gallery’s upper end imply mechanical or logistical functions that remain debated.

Below the King’s Chamber lies the Queen’s Chamber, a misnamed space that was likely never intended as a burial site.

Located centrally within the pyramid, it features a distinctive gabled roof and a tall niche in its eastern wall.

The absence of burial goods and the chamber’s architectural form have fueled theories that it served a ritual or symbolic function, possibly connected to rebirth or the spiritual transformation of the pharaoh.

Modern scanning technologies such as muon radiography and infrared imaging continue to probe the chamber’s walls for hidden voids or structural clues.

The pyramid’s internal complexity extends further with the Subterranean Chamber, carved roughly into the bedrock beneath the structure.

Unlike the polished stonework above, this chamber remains unfinished.

Its purpose is unknown.

Some suggest it was an abandoned early plan for a burial chamber, while others view it as a symbolic underworld representation consistent with Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife.

In recent years, scientific exploration has revealed an even greater mystery.

In 2017, researchers using muon radiography identified a massive void above the Grand Gallery.

Known as the Big Void, it stretches for at least thirty meters and appears to be a deliberate architectural feature rather than a structural flaw.

Its function is unknown.

It may have served as a weight-relieving space, a ceremonial chamber, or something entirely different.

The discovery underscores how much remains hidden within the Great Pyramid despite centuries of investigation.

Beyond the pyramid itself, attention has turned to lesser-known features on the Giza Plateau, including the Osiris Shaft.

Long overshadowed by the pyramids and the Sphinx, this vertical shaft descends through three levels deep into the bedrock.

Excavated extensively in the 1990s, the shaft revealed chambers, burial niches, and a large stone sarcophagus partially submerged in groundwater.

The design evokes Egyptian myths of death and rebirth associated with the god Osiris, ruler of the underworld.

Artifacts recovered from the Osiris Shaft suggest it dates to the New Kingdom, though its symbolic architecture may reference much older religious concepts.

Some scholars propose that the shaft functioned as a ritual space for initiation ceremonies, representing a descent into death followed by spiritual rebirth.

The presence of water at the lowest level reinforces parallels with Egyptian texts describing the underworld as a realm of primordial waters.

These discoveries have fueled broader debates about ancient knowledge and technology.

Writers such as Graham Hancock and researchers like Randall Carlson argue that mainstream archaeology underestimates the capabilities of prehistoric societies.

They suggest that evidence of advanced knowledge in astronomy, engineering, and mathematics points to the existence of earlier civilizations whose achievements were inherited by later cultures.

Central to these theories is the idea that a catastrophic global event occurred near the end of the last Ice Age, approximately twelve thousand years ago.

Known as the Younger Dryas, this period involved abrupt climate change, massive flooding, and rising sea levels.

Proponents argue that such an event could have destroyed coastal and low-lying civilizations, erasing much of their material evidence while preserving fragments of knowledge in myth, architecture, and oral tradition.

Supporters of this perspective often cite global flood myths, astronomical alignments in ancient monuments, and the precision of megalithic construction as indicators of a shared legacy.

Structures such as Stonehenge, the pyramids of Mesoamerica, and megalithic temples in Malta are presented as evidence of advanced observational astronomy and geometry long before conventional timelines allow.

Geologist Robert Schoch contributed to this debate with his controversial analysis of erosion patterns on the Great Sphinx.

He argued that the weathering visible on the monument was caused by prolonged rainfall rather than wind and sand, implying that the Sphinx may date to a much wetter period in Egypt’s past, potentially thousands of years earlier than traditionally believed.

While many Egyptologists dispute this interpretation, the argument has drawn attention to the need for interdisciplinary research.

Further complicating the picture are underwater discoveries such as the sunken city of Thonis Heracleion near the Nile Delta.

Rediscovered in the early twenty-first century, the city revealed extensive harbor structures, temples, statues, shipwrecks, and thousands of artifacts.

Its submergence was caused not by rising sea levels alone, but by geological subsidence and seismic activity.

The site demonstrates how entire urban centers can vanish from historical memory.

Similarly, underwater remains near Alexandria, including structures associated with Cleopatra’s royal quarter, show how political, cultural, and religious centers can be lost beneath the sea.

These discoveries challenge assumptions about the completeness of the archaeological record and raise questions about how much of humanity’s past remains hidden.

Critics of lost civilization theories argue that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

They point out that no definitive artifacts of advanced prehistoric technology have been found, and that myths cannot be treated as historical records without corroboration.

Nonetheless, proponents counter that catastrophic destruction, sea level rise, and geological processes could have erased much of the physical evidence, leaving only indirect traces.

What emerges from this ongoing debate is not a single conclusion, but a growing recognition of uncertainty.

The Great Pyramid, the Osiris Shaft, submerged cities, and anomalous geological features all demonstrate that ancient societies were capable of remarkable achievements.

Whether these accomplishments arose independently within known civilizations or reflect inheritance from earlier cultures remains unresolved.

As new technologies allow researchers to peer deeper into stone, soil, and sea, long-held assumptions continue to be tested.

Each discovery adds complexity rather than closure.

The monuments of ancient Egypt and beyond stand not only as symbols of past greatness, but as reminders that human history may be far more intricate than once believed.

News

Shocking: Jim Caviezel and Mel Gibson Reveal Behind-the-Scenes Secrets You’ve Never Heard Before

Behind one of the most controversial religious films ever produced lies a body of testimony that continues to unsettle those…

Ethiopian Monks Finally Translate The Resurrection Passage — And The Meaning Changes Everything

Ethiopia’s Ancient Christian Manuscripts Are Rewriting the Story of Faith Long before Europe defined Christian orthodoxy, built cathedrals, or convened…

Barrie Schwortz: “We Found Something on the Shroud of Turin That Scientists Can’t Explain

Whoever removed the burial cloth from the tomb after the crucifixion accepted a risk comparable to that faced by the…

PASTOR T.D. JAKES IS BACK IN THE HEADLINES, and the sudden surge of attention has left followers and critics alike asking uneasy questions. What recent developments are driving this renewed spotlight, and WHY ARE INSIDERS SAYING THERE’S MORE BEHIND THE STORY THAN WHAT’S BEING REPORTED? As statements, past moments, and behind-the-scenes movements resurface, speculation is growing fast.

IS THIS A TURNING POINT FOR ONE OF AMERICA’S MOST INFLUENTIAL FAITH LEADERS—or JUST THE BEGINNING OF A MUCH BIGGER RECKONING? 👉 CLICK THE ARTICLE LINK IN THE COMMENT to uncover the obscure details everyone is watching closely.

The Latest Developments Surrounding Pastor T.D.JakesPastor T.D.Jakes, a prominent figure in the world of ministry and leadership, has recently been…

Heavy D’s Death Wasn’t Just DISTURBING – It Was A RITUAL!

Heavy D, born Dwight Arrington Myers, was one of the most influential and beloved figures in hip hop history. Known…

End of content

No more pages to load