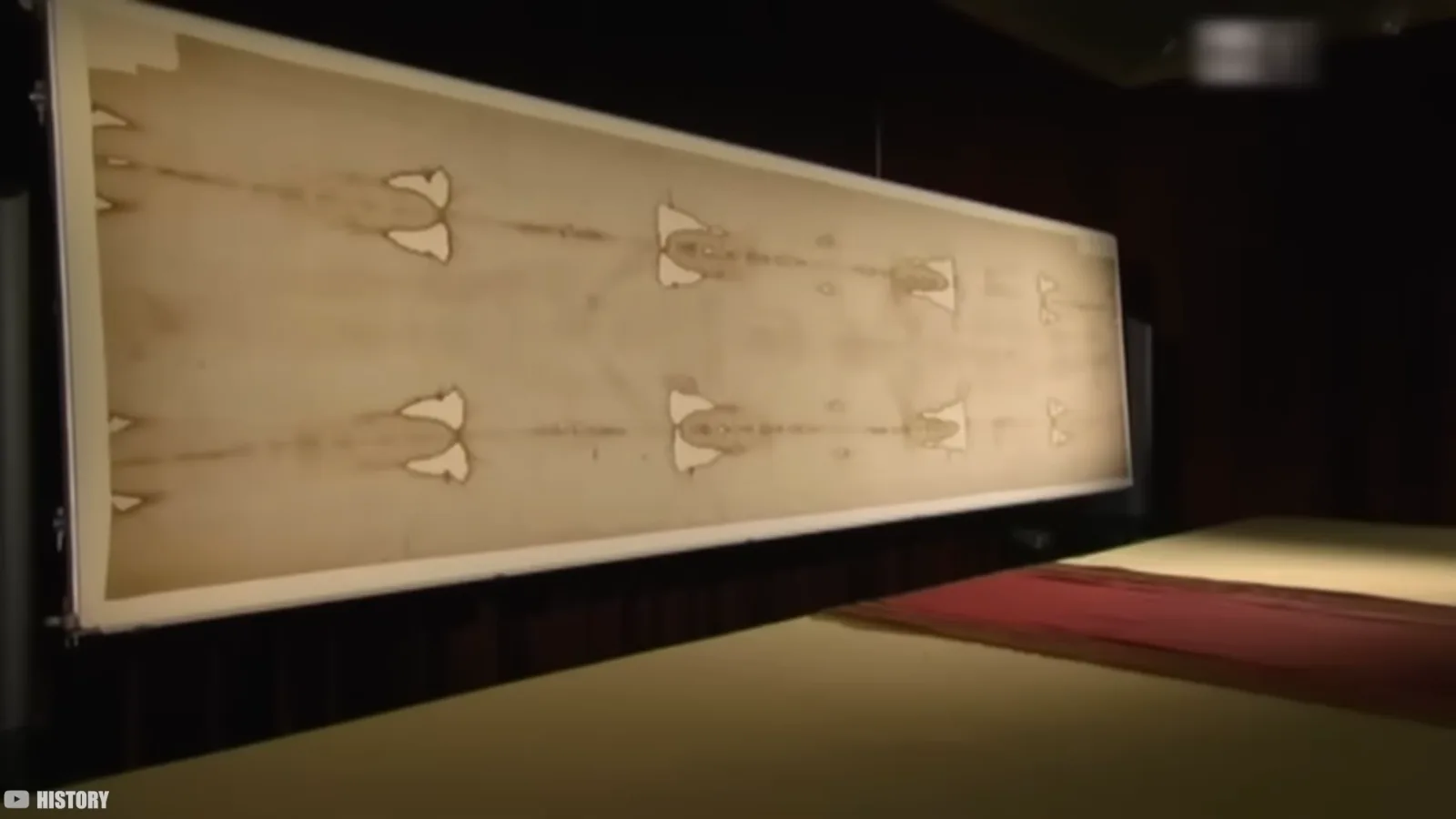

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated the imagination of believers, historians, and scientists alike.

This linen cloth, bearing the faint image of a crucified man, has inspired awe and controversy, prompting questions about faith, art, and the limits of scientific understanding.

What makes the Shroud remarkable is not merely its age but the mysterious qualities of the image it bears—qualities that have resisted explanation for over a hundred years.

The modern fascination with the Shroud began in 1898 when Secondo Pia, an Italian lawyer and amateur photographer, took the first photograph of the cloth.

Expecting a faint negative, Pia was astonished to find a strikingly clear positive image of a man on the photographic plate.

The revelation that the Shroud’s image resembled a photographic negative—an effect centuries before the invention of photography—captured worldwide attention and immediately raised questions about its origins.

Subsequent scientific examination only deepened the mystery.

The image is remarkably superficial, affecting only the topmost layer of linen fibers, approximately two hundred nanometers deep—thinner than most bacteria.

It is neither paint nor dye and does not penetrate the fabric.

The discoloration is instead a subtle chemical alteration, suggesting an extraordinary and unknown method of creation.

In the 1970s, NASA researchers applied the VP-8 image analyzer, a device designed for mapping planetary surfaces, to a photograph of the Shroud.

The results revealed that the shading of the image correlated with the distance between the cloth and the body beneath it, effectively encoding three-dimensional spatial information in a two-dimensional image—a property unparalleled in any known artwork of the medieval period.

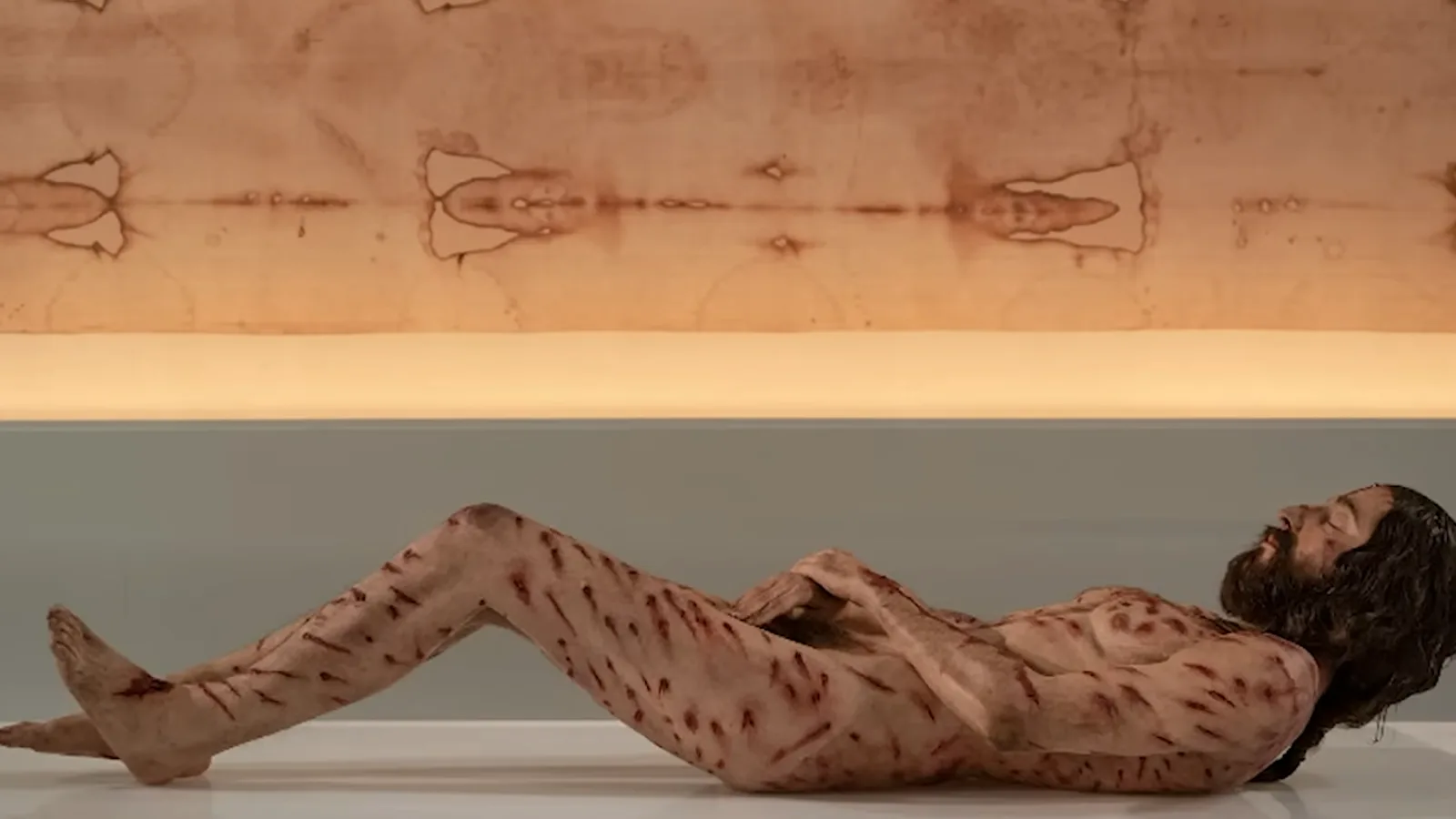

Adding to the complexity, the Shroud contains both the faint image and real human bloodstains.

The blood penetrated the cloth, while the image remained superficial.

Despite extensive experiments with heat, chemicals, radiation, and other techniques, no laboratory has been able to replicate these combined features, leaving the Shroud’s origin scientifically elusive.

For decades, much of the debate centered on the Shroud’s age.

In 1988, three independent laboratories—Oxford, Zurich, and Tucson—performed radiocarbon dating on a small corner of the cloth.

The results indicated a medieval origin, dating the Shroud between 1260 and 1390 AD.

This conclusion, widely reported in the media, seemed to settle the debate: the Shroud was a brilliant medieval forgery.

Yet questions about the validity of this dating emerged almost immediately.

Critics argued that the sample tested might have been taken from a repaired section of the cloth, which could have skewed the results.

Supporting this theory, later analysis suggested the tested fibers contained substances absent in other parts of the Shroud, such as cotton and plant-based coatings.

Additionally, some researchers noted that the Shroud had suffered significant fire damage in 1532, which could have altered its chemical composition.

Further scrutiny of the raw 1988 data revealed statistical inconsistencies among the laboratories, leaving room for doubt about the carbon dating verdict.

More recently, non-destructive techniques such as Wide Angle X-ray Scattering have suggested that the main body of the Shroud could be much older, potentially approaching two thousand years in age.

The tension between the image’s technological impossibility and the medieval dating led researchers to seek new approaches.

With the rise of artificial intelligence, some turned to neural networks to analyze high-resolution images of the Shroud.

The appeal of AI lay in its ability to detect patterns without handling the physical artifact, thus avoiding contamination or bias.

AI studies sparked sensational claims: some suggested that the image contained a hidden mathematical code or repeating geometric patterns, while others used AI-generated reconstructions to produce photorealistic images of the man depicted on the Shroud.

Enthusiasts interpreted these findings as evidence of divine design or even as a record of an extraordinary event, sometimes referred to as the “Resurrection Hypothesis.”

However, these claims have faced strong scientific criticism.

AI is prone to overfitting, finding patterns in noise that may not exist.

Many of the studies claiming a hidden code lack peer-reviewed validation, meaning they cannot be considered established science.

Similarly, AI-generated images are influenced by the training data used.

Since most online depictions of Jesus feature familiar Western characteristics, the resulting reconstructions are more reflective of historical artistic conventions than of historical reality.

Historians note that a first-century Galilean man would likely have had features significantly different from the AI-generated images.

Other experts propose more plausible non-miraculous explanations.

Some graphics specialists suggest that the Shroud’s image could have been created using a low-relief sculpture.

The cloth could have been pressed onto a raised form coated with pigment, producing a flat, two-dimensional image that nonetheless encodes 3D spatial information—a technique that could explain the image’s unusual properties without invoking supernatural intervention.

While this theory remains unproven, it demonstrates that creative medieval artistry could potentially account for some of the Shroud’s mysteries.

Even so, the Shroud continues to challenge scientific understanding.

Experiments attempting to replicate the image’s properties reveal the extreme difficulty of the task.

To recreate the superficial discoloration and 3D encoding simultaneously, an immense, precisely controlled energy release would be required.

Too little energy would leave the image faint or incomplete; too much would destroy the fabric.

Some physicists have proposed that the Shroud’s image may have been formed by a brief, intense burst of energy, producing a superficial imprint that encoded both the visual and structural information of the body beneath.

In this interpretation, the image could be seen not merely as a picture but as an “event record,” a preserved signature of an extraordinary interaction between matter and energy.

This perspective opens the possibility that the Shroud contains a form of encoded information.

Some researchers have suggested that microscopic, parallel structures within the fibers—so-called Phase Coherence Lines—may represent a kind of data compression, analogous to holographic storage.

When analyzed with advanced algorithms, these patterns could theoretically translate into harmonic ratios, spatial relationships, or other structural information.

In this sense, the Shroud could be interpreted as an ancient, unintentional form of information storage, encoding a message in the interplay of light, energy, and matter.

While highly speculative, this approach shifts the debate away from questions of authenticity or forgery and toward the nature of the image itself.

Despite the fascination and speculation, consensus remains elusive.

The Shroud of Turin is simultaneously a medieval artifact, a scientific anomaly, and a cultural icon.

Its age, method of creation, and the meaning of the image continue to be disputed.

Radiocarbon dating suggests a medieval origin, yet the physical properties of the image defy replication even with modern technology.

AI analysis highlights potential patterns but cannot confirm historical or miraculous claims.

Artistic, chemical, and physical studies offer hypotheses, but none can fully reconcile all observed phenomena.

Ultimately, the Shroud endures as both a mirror and a mystery.

Science sees an anomaly, faith sees a miracle, and technology raises new questions about the limits of knowledge.

Whether the Shroud represents a medieval masterpiece, a preserved historical relic, or an encoded record of an extraordinary event, it remains one of humanity’s most compelling enigmas.

In confronting it, researchers are challenged not only to decode its mysteries but also to grapple with the profound questions it poses about the intersection of history, art, science, and belief.

The ongoing study of the Shroud of Turin illustrates a broader truth: some artifacts resist simple categorization, demanding an interdisciplinary approach that spans chemistry, physics, history, and digital analysis.

As artificial intelligence and advanced imaging techniques continue to evolve, new insights may emerge, yet the Shroud’s ultimate secret may remain just out of reach, reminding humanity of the enduring power of mystery.

In the end, the Shroud challenges observers to consider not just how it was created, but why its story continues to fascinate and inspire debate centuries after it first appeared.

News

What Scientists Just FOUND Beneath Jesus’ Tomb in Jerusalem Will Leave You Speechless

Unearthing the Past: The Astonishing Discovery Beneath Jesus’ Tomb in Jerusalem Beneath one of the holiest sites in Christianity, an…

The VIRGIN MARY Warns Pope Leo XIV: What Is Coming Will SHAKE the World!

In a message that has captured the attention of the faithful around the world, the pontiff delivered a deeply personal…

After Nearly 2,000 Years, New Evidence Reveals Queen Cleopatra’s Tomb Beneath a Sunken Port!

For over two millennia, the final resting place of Cleopatra VII, the last queen of Egypt, has remained one of…

Finally Cleopatra’s Tomb Found? Egypt’s Biggest Discovery in 2,000 Years!

For centuries, the location of Cleopatra VII’s final resting place has captivated historians, archaeologists, and the public alike. As the…

Amelia Earhart Investigator Ric Gillespie CONFIRMS the Location of Her Emergency Landing

Amelia Earhart’s disappearance over the Pacific Ocean in 1937 remains one of the most enduring mysteries in aviation history. For…

Why Was King Tut’s Tomb Prepared in Such a Rush?

The discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 by British archaeologist Howard Carter remains one of the most extraordinary moments…

End of content

No more pages to load